Normal Bladder Anatomy and Variants of Normal Histology

Understanding the normal anatomy of the bladder is of paramount importance since its landmarks are used to stage, establish clinical risk, and select therapy in cases of bladder cancer. One must also be aware that local injury, instrumentation, and prior therapy can influence the appearance of the bladder wall as well as the overlying urothelium significantly.

The epithelium of the urinary bladder and urethra is entirely derived from endoderm of the urogenital sinus, while the lamina propria, muscularis propria, and adventitia develop from the surrounding splanchnic mesenchyme. Despite their different histogenesis, all of the urinary excretory passages are lined by so-called transitional epithelium, which is better referred to as urothelium, a term that we will use throughout this book. During early embryologic development, the caudal portions of the mesonephric ducts contribute to the formation of the mucosa of the bladder trigone but are eventually replaced by endoderm (1).

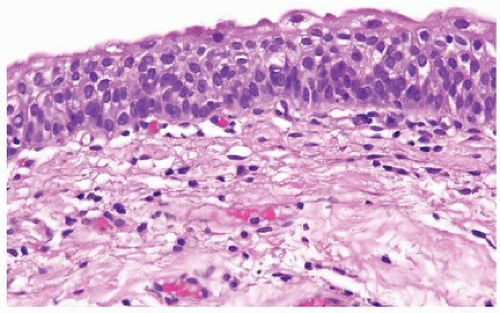

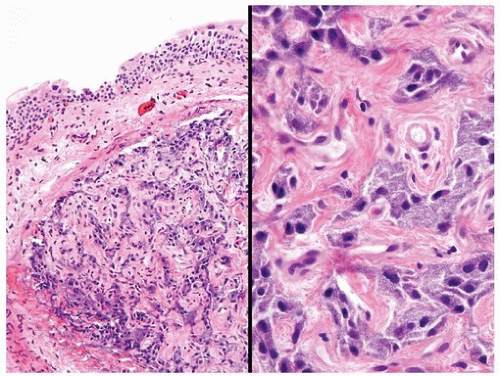

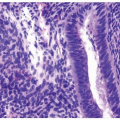

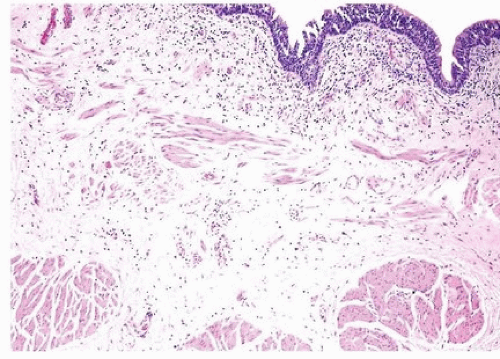

The urinary bladder is formed by four layers: (a) urothelium, (b) lamina propria, (c) muscularis propria, and (d) adventitia or serosa (efigs 1.1-1.5). Depending on the location, these layers may be surrounded by perivesical fat (2, 3). The thickness of the urothelium varies, as does the shape of the epithelial cells, depending on the degree to which the bladder is distended. In the empty bladder, the epithelium can be up to seven cells thick. The deepest (basal) cells have a cuboidal or columnar shape, above which are the intermediate cells that are composed of several layers of irregularly polyhedral to columnar cells (Fig. 1.1). The most superficial or luminal layer consists of large, sometimes binucleated, cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and a rounded free surface. They are descriptively called umbrella or superficial cells (2). In the distended bladder, the epithelial lining can be as few as two cells thick, with a basal layer of cuboidal cells and a superficial layer of elongated and flattened umbrella cells (see Chapter 2 for histology of normal urothelium).

A thin basement membrane separates the urothelium from the underlying lamina propria. The latter is formed of abundant connective tissue containing a rich vascular network, lymphatic channels, sensory nerve endings, and a few elastic fibers. We prefer the term lamina propria over

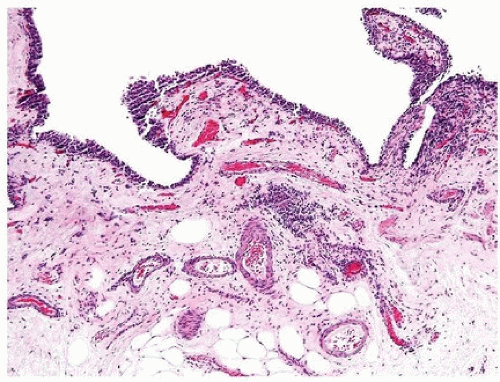

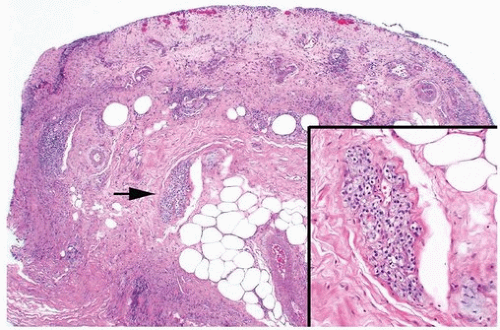

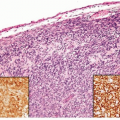

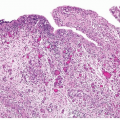

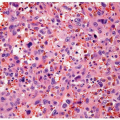

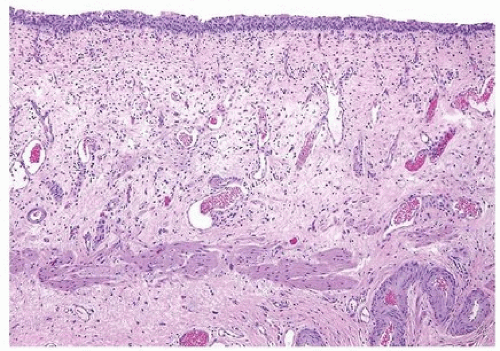

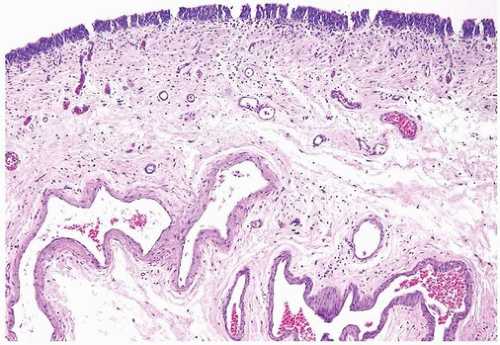

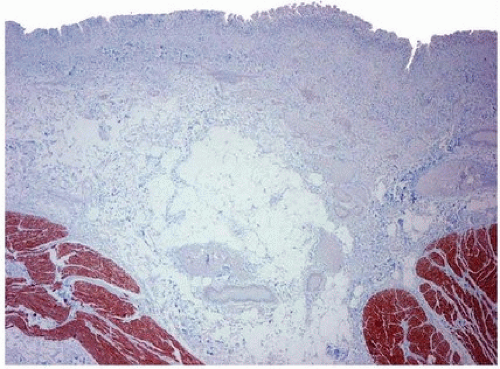

submucosa in the bladder since a muscularis mucosae, if present, is usually discontinuous. The term submucosa is used for the layer of tissue between the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria. In the ureter and pelvicalyceal mucosa where there is no muscularis mucosae, the term submucosa is more appropriate. This nomenclature is also used in the AJCC staging systems for the respective sites (bladder, ureter, and pelvis), which is based on the paradigm of depth of invasion in tumors. In the bladder, the lamina propria varies in thickness in the empty versus the distended bladder but is generally thinner in the areas of the trigone and bladder neck. It is unlikely to encounter muscularis mucosae at these sites since muscularis propria extends closer to the urothelial surface. It is important to note that wisps or small fascicles of smooth muscle may be found within the superficial lamina propria, either isolated or forming a complete or incomplete muscularis mucosae (3, 4, 5, 6) (Figs. 1.2, 1.3) (efigs 1.5-1.9). This muscularis mucosae, if present, is frequently seen in association with medium-sized vessels, which are also prominently seen within the lamina propria (Fig. 1.4). It must not be confused with the smooth muscle bundles of the muscularis propria since this might result in errors of tumor staging and treatment. Occasionally, the muscularis mucosae may take on a hyperplastic appearance (5, 6). The most common setting is when the muscle fascicles are thick rather than wispy, even though they retain haphazard outlines. On rare occasions, the muscularis mucosae may present as muscularis propria-like muscle bundles but characterized by a superficial location and scattered distribution. On small or superficial biopsies, these may be impossible to distinguish from true muscularis propria. It may also be impossible to make this determination at site of prior biopsy where the normal anatomy is disrupted. The muscularis mucosae may also become hyperplastic in association with bladder diverticula where it can take on a thick, band-like appearance without the formation of muscle bundles. Some studies suggest that smoothelin is differentially expressed in the muscularis mucosae as compared to the muscularis propria, with the latter positive while the former is either negative or only weakly and focally immunoreactive (Fig. 1.5) (7, 8). However, the utility of this antibody in routine practice remains controversial (9). We and others have noticed that there may be differential expression of vimentin with muscularis mucosae exhibiting strong staining, whereas muscularis propria tends to be either negative or weak. It is also important to note that one may encounter fat within the lamina propria as well as in the muscularis propria (10) (Figs. 1.6, 1.7) (efigs 1.10-1.12). Fat may be found in bladders that have never been instrumented or in areas of prior transurethral resection. Whether its presence is due to a normal anatomic variant, a function of the patient’s body habitus, or a metaplastic phenomenon is not known. What is important is that the presence of invasive tumor at the level of smooth muscle or fat in a transurethral resection specimen does not necessarily warrant a diagnosis of muscularis propria invasion or extravesical extension, respectively. Within the lamina propria, one may also encounter paraganglia, commonly in intimate association with small-caliber vessels or nerve twigs (Figs. 1.8, 1.9). These usually present as small aggregates of cells with basophilic granular cytoplasm and small- to medium-sized round nuclei. In a small biopsy, these aggregates may be difficult to differentiate for a bona fide paraganglioma or even invasive carcinoma. As expected, paraganglia will be strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for chromogranin but negative for cytokeratins. Dispersed paraganglia may also be encountered within the muscularis propria and perivesical fat. Rarely, one may encounter urachal remnants in biopsies of the dome or anterior wall of the bladder. These present as one of several epithelial-lined structures in which the epithelial cells have the morphologic appearance of urothelium or glandular (usually enteric) epithelium. These cells are lined by an imperceptible basement membrane and a variably thin layer of fibromuscular tissue. Rarer yet, one may encounter müllerian or mesonephric rests within the bladder wall. The morphology and clinical repercussions of these lesions are discussed in Chapter 8.

submucosa in the bladder since a muscularis mucosae, if present, is usually discontinuous. The term submucosa is used for the layer of tissue between the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria. In the ureter and pelvicalyceal mucosa where there is no muscularis mucosae, the term submucosa is more appropriate. This nomenclature is also used in the AJCC staging systems for the respective sites (bladder, ureter, and pelvis), which is based on the paradigm of depth of invasion in tumors. In the bladder, the lamina propria varies in thickness in the empty versus the distended bladder but is generally thinner in the areas of the trigone and bladder neck. It is unlikely to encounter muscularis mucosae at these sites since muscularis propria extends closer to the urothelial surface. It is important to note that wisps or small fascicles of smooth muscle may be found within the superficial lamina propria, either isolated or forming a complete or incomplete muscularis mucosae (3, 4, 5, 6) (Figs. 1.2, 1.3) (efigs 1.5-1.9). This muscularis mucosae, if present, is frequently seen in association with medium-sized vessels, which are also prominently seen within the lamina propria (Fig. 1.4). It must not be confused with the smooth muscle bundles of the muscularis propria since this might result in errors of tumor staging and treatment. Occasionally, the muscularis mucosae may take on a hyperplastic appearance (5, 6). The most common setting is when the muscle fascicles are thick rather than wispy, even though they retain haphazard outlines. On rare occasions, the muscularis mucosae may present as muscularis propria-like muscle bundles but characterized by a superficial location and scattered distribution. On small or superficial biopsies, these may be impossible to distinguish from true muscularis propria. It may also be impossible to make this determination at site of prior biopsy where the normal anatomy is disrupted. The muscularis mucosae may also become hyperplastic in association with bladder diverticula where it can take on a thick, band-like appearance without the formation of muscle bundles. Some studies suggest that smoothelin is differentially expressed in the muscularis mucosae as compared to the muscularis propria, with the latter positive while the former is either negative or only weakly and focally immunoreactive (Fig. 1.5) (7, 8). However, the utility of this antibody in routine practice remains controversial (9). We and others have noticed that there may be differential expression of vimentin with muscularis mucosae exhibiting strong staining, whereas muscularis propria tends to be either negative or weak. It is also important to note that one may encounter fat within the lamina propria as well as in the muscularis propria (10) (Figs. 1.6, 1.7) (efigs 1.10-1.12). Fat may be found in bladders that have never been instrumented or in areas of prior transurethral resection. Whether its presence is due to a normal anatomic variant, a function of the patient’s body habitus, or a metaplastic phenomenon is not known. What is important is that the presence of invasive tumor at the level of smooth muscle or fat in a transurethral resection specimen does not necessarily warrant a diagnosis of muscularis propria invasion or extravesical extension, respectively. Within the lamina propria, one may also encounter paraganglia, commonly in intimate association with small-caliber vessels or nerve twigs (Figs. 1.8, 1.9). These usually present as small aggregates of cells with basophilic granular cytoplasm and small- to medium-sized round nuclei. In a small biopsy, these aggregates may be difficult to differentiate for a bona fide paraganglioma or even invasive carcinoma. As expected, paraganglia will be strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for chromogranin but negative for cytokeratins. Dispersed paraganglia may also be encountered within the muscularis propria and perivesical fat. Rarely, one may encounter urachal remnants in biopsies of the dome or anterior wall of the bladder. These present as one of several epithelial-lined structures in which the epithelial cells have the morphologic appearance of urothelium or glandular (usually enteric) epithelium. These cells are lined by an imperceptible basement membrane and a variably thin layer of fibromuscular tissue. Rarer yet, one may encounter müllerian or mesonephric rests within the bladder wall. The morphology and clinical repercussions of these lesions are discussed in Chapter 8.

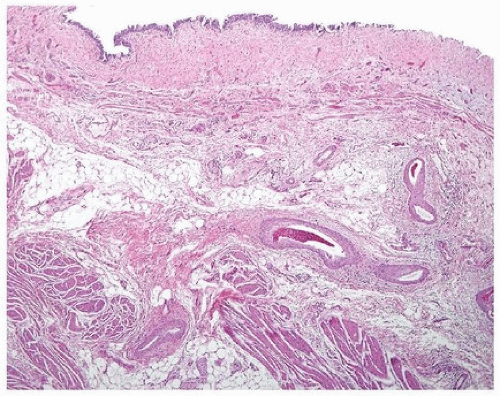

FIGURE 1.2 Normal histology with urothelium, lamina propria with muscularis mucosae, and muscularis propria. |

FIGURE 1.3 Normal histology with urothelium, lamina propria with muscularis mucosae, and muscularis propria. |

FIGURE 1.4 Normal histology with urothelium, lamina propria, and numerous prominent blood vessels at the level of the muscularis mucosae. |

FIGURE 1.5 Smoothelin with strong labeling of muscularis propria. Muscularis mucosae only shows weak positivity. |

The vascular plexus of the lamina propria, although most classically associated with the muscularis mucosae, may vary somewhat in location from case to case and section to section. Similar to the muscularis mucosae, it may be seen in a superficial, mid, or deep location.

The muscularis propria, also known as detrusor muscle, has loosely anastomosing, ill-defined internal and external longitudinal layers and a more prominent middle circular layer of muscle (Fig. 1.10). The bundles of muscle of the muscularis propria are generally much larger than those of

the muscularis mucosae, a feature that is useful as an anatomic landmark. In the bladder neck of the male, the fascicles of the muscularis propria are continuous with the fibromuscular tissue of the prostate (Fig. 1.11) (2). In the trigone and bladder neck area, the muscularis propria is distinct in that there is a gradual diminution of size and organization of the muscle bundles as they extend to an almost suburothelial location; in these sites, a well-defined distinct overlying muscularis mucosae is not present (Fig. 1.12). As previously mentioned, fat may be present between the muscle bundles of the muscularis propria (10).

the muscularis mucosae, a feature that is useful as an anatomic landmark. In the bladder neck of the male, the fascicles of the muscularis propria are continuous with the fibromuscular tissue of the prostate (Fig. 1.11) (2). In the trigone and bladder neck area, the muscularis propria is distinct in that there is a gradual diminution of size and organization of the muscle bundles as they extend to an almost suburothelial location; in these sites, a well-defined distinct overlying muscularis mucosae is not present (Fig. 1.12). As previously mentioned, fat may be present between the muscle bundles of the muscularis propria (10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree