The disease processes discussed in this chapter are uncommon tumors: phyllodes tumors, sarcomas, lymphomas, melanomas, and metastases to the breast. As a group, these tumors are rare and heterogeneously diverse. Given their small numbers, there have been few large patient series or trials, and no large prospective trials will likely be performed. The majority of the literature consists of single-institution, retrospective studies/case reports with small numbers, varied follow-up, and inherent biases. Furthermore, these studies are difficult to compare as the definition, management, and treatment of these tumors have changed over time. Therefore, there are no established guidelines for the treatment of these uncommon tumors; patients with these rare tumors should be managed in a multidisciplinary fashion.

Phyllodes tumors represent a spectrum of fibroepithelial neoplasms that have biological behavior that is diverse and unpredictable. They account for less than 1% of all breast neoplasms.1,2 These tumors have also been referred to as cystosarcoma phyllodes, phylloides tumors, and periductalstromal tumors. The term cystosarcoma phyllodes was first introduced in 1838 by Johannes Mueller; “sarcoma” for the fleshy nature of the tumor and “phyllodes” for its leaf-like architecture.3 Mueller emphasized the benign nature of this tumor. The first report of histologically malignant features in these tumors was by Lee and Pack in 1931.4 In 1960, Lomonaco proposed the name tumor phyllodes to avoid any implications of biological behavior.5 The World Health Organization proposed phyllodes tumor to emphasize the putative origin of these tumors from specialized periductal stroma and to avoid the designation of sarcoma with its deceptive implication of malignancy for a majority of these tumors.6 These tumors can arise de novo, and less frequently from preexisting fibroadenomas or from the malignant transformation of benign phyllodes tumors.2

Phyllodes tumors occur over a wide age range from adolescents to the elderly, with the majority of tumors occurring in women in their 40s to 50s.1,2,7,8 These tumors can occur in young children and men. Women usually present with a palpable, firm-hard, discrete, mobile mass with an average size of 4 to 5 cm. Most tumors are unilateral and painless. Some women may give a history of a stable mass that grows rapidly. Larger tumors may cause stretching of the overlying skin and ulceration. All of these findings can be seen in both benign and malignant tumors. Compared with fibroadenomas, phyllodes tumors are seen more frequently in older patients and those with a history of rapid tumor growth and/or larger tumors. Palpable axillary lymphadenopathy can be identified in up to 20% of patients but is usually due to reactive changes as metastatic involvement is rare.9-11 In some instances, tumors may be multifocal, bilateral, or occur in ectopic breast tissue. In 1% to 2% of cases, an in situ or invasive breast carcinoma occurs within a phyllodes tumor.12 Also, patients can have a concurrent phyllodes tumor with a noninvasive or invasive breast carcinoma.1,2

Radiographically, there are no distinct imaging characteristics that can reliably distinguish a fibroadenoma, a benign phyllodes tumor, or a malignant phyllodes tumor.2,13,14 On mammography, most tumors are indistinguishable from fibroadenomas. They are round, well-circumscribed densities with smooth borders. Calcifications are uncommon but can be seen in both benign and malignant phyllodes tumors. On ultrasound, these lesions are discrete, hypoechoic, solid structures that may have scattered cystic regions. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), tumors are oval, round, or lobulated circumscribed masses with rapid enhancement and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.14

A fine-needle aspiration and/or percutaneous core needle biopsy of the lesion can be performed.7 However, the cytologic and limited histologic features obtained from a small biopsy may sometimes by difficult to interpret due to sampling artifact and the varied nature of the tumor. For these reasons, the distinction between a fibroadenoma from a phyllodes tumor may be difficult and surgical excision is recommended, especially in older patients and those with a large tumor or history of rapid growth of the tumor. Since these lesions resemble fibroadenomas clinically and radiographically, the clinical suspicion for a phyllodes tumor is important. Furthermore, most phyllodes tumors are not diagnosed preoperatively and therefore are shelled out/enucleated at initial surgery, usually resulting in inadequate surgical margins. Therefore, all surgical specimens should be oriented and a close examination of the margins should be performed.

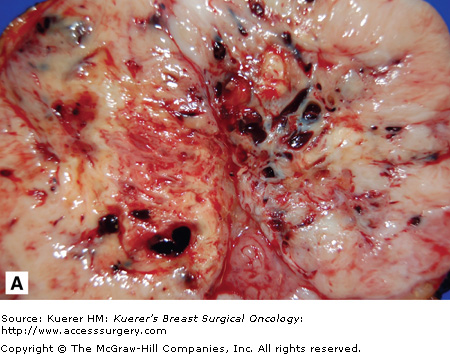

Phyllodes tumors are highly variable in their gross appearance.2 The majority are well-circumscribed, solid, grayish white, yellow, or pink fleshy masses with cystic areas. Foci of necrosis and hemorrhage may be seen in larger tumors (Fig. 23-2A). Tumors range in size from 1 to 45 cm, but on average are 4 to 5 cm in diameter. A true histologic capsule is absent. On gross examination, these tumors do not appear distinctly different from fibroadenomas.

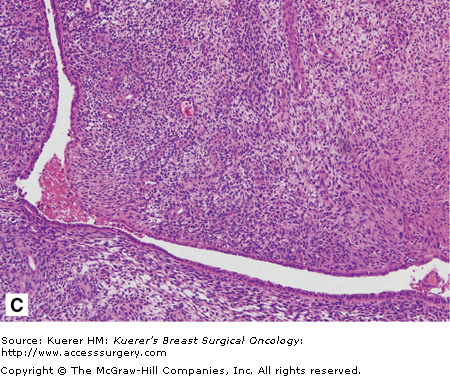

Figure 23-2

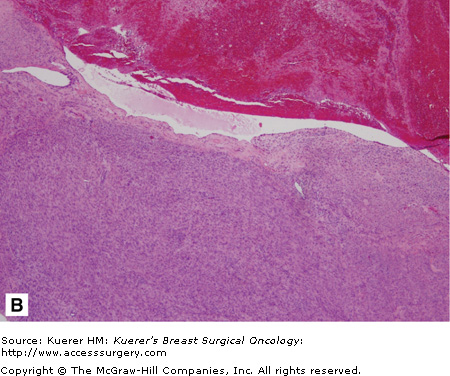

Malignant phyllodes tumor. A. The cut surface of a phyllodes tumor demonstrating a cleft appearance, resulting from the prominent intracanalicular growth pattern that is usually present. Usually firm and rubbery, phyllodes tumors may have gelatinous areas with foci of necrosis and hemorrhage as seen here. These features are suggestive of malignancy. B. A histologic section from the same tumor shows a dilated, blood-filled space adjacent to an area of marked stromal overgrowth. Note the absence of an epithelial component in this low-power view. C. Other areas of this tumor show the diagnostic biphasic architecture. This densely cellular stroma shows nuclear hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, and increased mitotic figures.

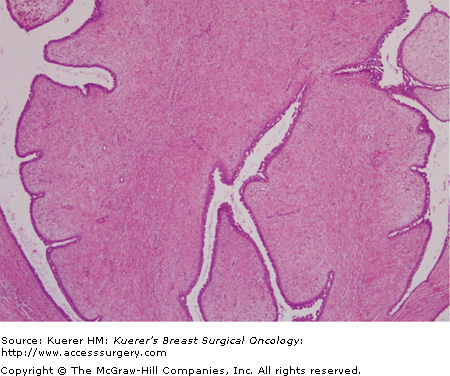

Histologically, these biphasic fibroepithelial tumors are composed of benign epithelial elements and mixed connective tissue (stroma). These tumors arise from the periductal stroma. They have a broad range of appearances, but the hallmark is the hypercellular mesenchymal component with stromal overgrowth. This stromal overgrowth accounts for the characteristic leaflike architecture produced by large areas of stroma surrounding clefts lined by epithelial cells (Fig. 23-1). The degree of stromal cellularity and stromal overgrowth resulting in the presence of a leaflike architecture distinguishes a phyllodes tumor from a fibroadenoma. These tumors must be differentiated from juvenile fibroadenomas, cellular fibroadenomas, metaplastic carcinomas, and primary breast sarcomas.

Phyllodes tumors are classified as benign, borderline/low-grade malignant, or malignant based on the mitotic activity, type of margin (infiltrative or pushing), stromal overgrowth, and cellular pleomorphism (Table 23-1).12,15 Overall, more than 50% of tumors are benign and approximately 25% are malignant.1 Although this classification system is widely used, the clinical course of a phyllodes tumor cannot be accurately predicted by its histopathologic features.9,11,16,17 The degree of stromal overgrowth may be the most important histologic feature for predicting the metastatic behavior of a phyllodes tumor (Fig. 23-2A, B, and C).10,16-18

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Benign | Borderline | Malignant |

| Mitotic rate (per 10 hpf) | < 5 | 5-9 | ≥10 |

| Tumor margins | Pushing | Pushing–infiltrative | Infiltrative |

| Stromal cellularity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Pleomorphism | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

In general, benign phyllodes tumors have an approximately 5% to 20% local recurrence rate but do not metastasize.9,11,19 Recurrences are usually benign. Borderline tumors have a greater than 25% risk of local recurrence, usually within the first 2 years; these recurrences may be malignant.11 The risk for distant metastases is less than 5%. Malignant tumors have a 20% to 40% risk of local recurrence and distant metastases.9,19 These recurrences usually occur earlier after the initial treatment than for borderline and benign cases. Distant metastases can occur without an antecedent local recurrence.1,2,11 Less than 1% of patients have axillary lymph node involvement.11,17 The clinical course, in most cases, is indolent. Overall 5-year survival rates are 75% to 88% and 10-year survival rates are 57% to 80%.8,9,16

Phyllodes tumors are treated surgically by wide local excision with negative margins, preferably more than 1 cm for definitive local control.1,2,9,11,16,18,20 Since these tumors are surrounded by a pseudocapsule of dense, compressed, normal surrounding tissue that contains microscopic projections of the lesion, achieving a 1-cm histologic margin will often require a gross 2- to 3-cm margin. Since mastectomy and wide local excision with adequate margins have similar local recurrence rates and overall survival rates, mastectomy should be reserved for large tumors or lesions with infiltrating margins and aggressive histologic features that would not allow for local excision with an adequate margin and/or acceptable cosmetic result.1,2,8,16 Since phyllodes tumors rarely metastasize to axillary lymph nodes, there is no role for routine axillary lymph node dissection.

As most phyllodes tumors are diagnosed after excisional biopsy, the margin status of many cases may be suboptimal, and the decision to undergo a reexcision must be determined. Positive/close margin status is the most powerful independent predictor of local recurrence.9-11,18-20 The local recurrence rates for tumors that are excised “locally” with positive margins or margins of only a few millimeters are 21%, 46%, and 65% for benign, borderline, and malignant tumors, respectively; local recurrence rates for tumors that are widely excised with 1 to 2 cm margins are 8%, 29%, and 36% for benign, borderline, and malignant tumors, respectively.21 Some authors advocate re-excision in all patients with a less than 1-cm margin, especially those with malignant tumors, while others propose close observation, especially in those patients with benign/borderline tumors in whom reexcision may be technically difficult or cosmetically deforming.9,20,21

There is no clearly defined role for adjuvant radiation therapy, as most studies are anecdotal case reports and no series has shown a clear benefit for radiation therapy in the primary treatment of phyllodes tumors.16,19,22 Adjuvant radiation therapy (50-60 Gy) has been recommended for malignant tumors and tumors greater than 5 cm; it has also been considered in patients for whom negative margins have not been attained.7,10,16,19 Similarly, there is no proven role for adjuvant chemotherapy or hormonal therapy in reducing recurrences or deaths.1,2,7 Given the high rate of distant metastases in patients with excessive stromal overgrowth, especially if the tumor size is greater than 5 cm, Chaney and associates recommend considering chemotherapy in this cohort.16

Given the risk of local recurrence, patients should be followed closely with a clinical breast examination and baseline mammography within 4 to 6 months of surgery. Clinical breast examination and imaging (mammography with or without ultrasonography) should be recommended every 6 months for 5 years, and annually thereafter.7 For patients with malignant phyllodes tumors, biannual chest/abdominal CT scans for 2 to 5 years can be considered, although the benefits of this screening regimen are unproven.

Overall, local recurrence occurs in 15% to 30% of patients, usually within the first 2 to 3 years after initial diagnosis.9,20 Time to local recurrence is shortest among those with malignant tumors.15 Generally, most recurrences recur with the same histology as that of the initial tumor; however, cases of transformation to a more aggressive tumor have been reported.1,16,20 Recurrences can be managed by reexcision with wide margins or total mastectomy with or without reconstruction. Salvage mastectomy for recurrent disease does not affect overall survival.16 Adjuvant radiation therapy to the breast/chest wall after reexcision with negative margins can be considered.23

Overall, distant metastasis occurs in about 5% to 10% of patients; however, it occurs in up to 20% to 40% of patients with malignant tumors. Metastases occur via hematogenous spread, most commonly to lung, liver, bone, mediastinum, and brain. Metastases usually occur within the first 3 years of diagnosis; death occurs approximately 2 to 3 years after the development of metastatic disease.1,8,9,17 The degree of stromal overgrowth may be the most important histologic feature for predicting the metastatic behavior of a phyllodes tumor.10,16-18 Due to limited numbers and experiences, the optimal treatment (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, palliative radiation therapy) of metastatic disease has not been determined.9,10,17,21 Chemotherapeutic agents have included cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, cisplatin and doxorubicin, and etoposide and cisplatin.1,17 Responses, when they occur, are usually of short duration. Given such limited experience, the management of metastatic phyllodes tumors should follow the guidelines for treatment of advanced extremity/truncal sarcoma.24

Phyllodes tumors are uncommon, heterogeneously diverse tumors that are often misdiagnosed as fibroadenomas. These tumors are biphasic, composed of an epithelial and stromal component, and can be classified as benign, borderline, or malignant based on histology. Overall, these tumors have a propensity to recur locally. Distant metastases may develop in 5% to 15% of patients overall but in over 20% of patients with malignant tumors. Phyllodes tumors, including those that are malignant, have a long-term survival > 90%. Definitive treatment is wide local excision with a 1-cm or larger margin. The role of adjuvant radiation therapy and systemic therapy remains unproven and must be considered, especially in those patients with excessive stromal overgrowth, on an individual basis in a multidisciplinary fashion. Patients with local recurrences should be managed with wide excision with or without subsequent radiation therapy. Patients with metastatic disease should be managed according to treatment guidelines similar to patients with metastatic extremity soft-tissue sarcomas.

Sarcomas of the breast include a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors that arise from the mammary stroma. These mesenchymal tumors account for less than 1% of all malignant breast neoplasms and less than 5% of all soft-tissue sarcomas.25-27 The most common subtypes are angiosarcoma, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, undifferentiated high-grade sarcoma (malignant fibrous histiocytoma, MFH), and fibrosarcoma. The etiology of primary breast sarcomas is largely unknown; saline prostheses have been previously implicated as a possible risk factor, but most recent data do not appear to support a relationship.27 Previous radiation therapy to the breast/chest wall and/or a history of lymphedema to the breast or upper extremity are established risk factors for angiosarcomas (discussed later in the chapter). As with sarcomas originating in other areas of the body, these tumors rarely spread to regional lymph nodes, and distant metastases occur most commonly to the lung, bone, and liver.25,26,28-31 Treatment is primarily surgical.

Primary breast sarcomas are typically seen in women in their 40s to 50s (range, 16 to 81 years).25-32 Most women present with a well-circumscribed, firm, mobile, painless, unilateral mass, which may be difficult to distinguish from a fibroadenoma. The suspicion for a primary breast sarcoma should be raised if there is a history of rapid tumor growth.25,28,30 These tumors vary in size but typically are 5 to 6 cm in diameter.26,27,30-32 Other features, such as nipple discharge, nipple inversion, and skin changes (excluding angiosarcomas), are rarely seen.

On mammography and ultrasonography, these lesions are typically well-circumscribed, solid, nonspiculated masses.27,33 Breast CT/MRI and whole-body PET scans have not been extensively studied in primary breast sarcomas but could potentially be used in the evaluation of these patients.24,33 Preoperative chest x-ray should be performed in all patients given the risk of hematogenous spread to the lungs, especially from a high-grade sarcoma.24

Primary sarcomas of the breast represent a heterogeneous group of tumors. Grossly, these tumors are usually fleshy, moderately firm tumors with varying degrees of hemorrhage and necrosis. The specific histologic findings for the more common mesenchymal tumors are summarized below. In general, given the heterogeneous nature of these tumors, the importance of adequate sampling for accurate diagnosis must be emphasized. Histologic evaluation and immunohistochemical stains can help distinguish primary breast sarcomas from sarcomatous overgrowth in a phyllodes tumor, sarcomatoid carcinoma/carcinosarcoma, fibromatosis, metaplastic carcinoma, and malignant myoepithelioma.34

Tumors are staged by the 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system; staging is dependent on tumor location/depth, tumor size, histologic grade, and presence of nodal or distant metastases (Table 23-2).24,35 Tumor grade plays an important role in prognosis.

| TNM Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor 5 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T1a | Superficial tumor* |

| T1b | Deep tumor |

| T2 | Tumor more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2a | Superficial tumor* |

| T2b | Deep tumor |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastases (M) | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Histologic Grade | |

| GX | Grade cannot be assessed |

| G1 | Well differentiated |

| G2 | Moderately differentiated |

| G3 | Poorly differentiated |

| G4 | Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated (four-tiered systems only) |

There are currently no consensus guidelines or randomized trials that have specifically addressed primary breast sarcomas. The mainstay of treatment remains wide local excision with histologically negative margins (optimally 2-3 cm); en bloc resection of underlying muscle may be required. If negative margins can be achieved by breast-conserving surgery, there is no additional benefit to patients who undergo a mastectomy.25,26,28-32 Therefore, attempts at breast preservation are reasonable; however, total mastectomy may be required to achieve negative margins depending on tumor size, type, and/or location.27 Since tumors rarely metastasize to the regional lymph nodes, there is no role for routine axillary lymph node dissection. Local recurrences are typically treated with reexcision and radiation therapy, if not previously administered.

Potential prognostic features that have been studied include tumor grade, tumor size, cellular appearance, presence of infiltrating borders, mitotic activity, stromal atypia, and margin status. Although not universally replicated, prognostic factors that have more consistently been shown to have an adverse outcome (local recurrence and distant metastasis) include high histologic grade, larger tumor size (> 5 cm), and inadequate margins.25-32,36

Few data exist on the use of radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting.25,26,28-32,35,37 A few retrospective studies have shown that adjuvant radiation therapy provides excellent local control and improves disease-free survival but not overall survival.26,28,38 Although there is no definitive evidence, some have proposed that adjuvant radiation therapy be considered in patients with high-grade tumors, especially those larger than 5 cm, and those with positive margins in whom repeat surgery may not be feasible.25,29,30 As there are no adjuvant chemotherapy studies that have been completed in breast sarcoma patients, chemotherapy regimens for these patients have been based on data from other soft-tissue sarcomas.39,40 The results from the Sarcoma Meta-Analysis Collaboration of 14 randomized trials (1568 patients) showed that doxorubicin-based chemotherapy prolongs relapse-free survival and decreases recurrence rates in adults with localized, resectable soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremity.39 For breast sarcoma patients, those with high-grade tumors, especially those greater than 5 cm in size, should be considered for chemotherapy given their high risk for recurrent/metastatic disease.30,32,36 The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast sarcomas has not been recommended routinely given the fact that response rates are limited and most sarcomas are amenable to surgical resection at the time of presentation.30

Overall, it appears that patients with primary mammary sarcoma have a similar natural history, prognostic factors, and outcome after multimodality therapy as those with extremity sarcoma; 5-year overall survival rates range from 45% to 66%.25-28,30-32,36 The 5-year disease-free survival rates range from 28% to 52% and most failures occur within the first 1 to 3 years.25-32,36 Local recurrences occur in up to one-third of patients, highlighting the importance of a negative surgical margin. Breast sarcomas metastasize most commonly to the lung, bone, and liver. Other sites of metastases include the brain, skin, subcutaneous tissue, spleen, and adrenal glands.27,28 Management of metastatic disease may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and ablative or embolization procedures.24 In general, most patients with advanced primary breast sarcoma should be managed by established guidelines for patients with extremity sarcoma.24,32,36

Patients with stage I disease should be followed every 3 to 6 months for 2 to 3 years then annually; chest x-ray can be considered every 6 to 12 months. Patients with stage II to IV disease should undergo clinical examinations and chest x-ray or CT scan every 3 to 6 months for 2 to 3 years, and then every 6 months for the next 2 years, and then annually.24 For all patients, baseline ipsilateral mammography should be performed 6 months postoperatively in those who undergo breast-conserving surgery, and then bilateral mammography should be performed annually.

Angiosarcomas are malignant vascular neoplasms of the breast that typically have a more aggressive clinical course with higher recurrence rates and lower overall survival than other breast sarcomas.25,27,30-32,36,41 These tumors have also been called hemangiosarcoma, hemangioblastoma, malignant hemangioendothelioma, angioblastoma, and benign metastasizing hemangioma. Angiosarcomas arise in the breast more frequently than any other organ. They may arise de novo within the breast parenchyma (primary angiosarcoma) or as a secondary tumor associated with lymphedema (Stewart–Treves syndrome due to postmastectomy changes, congenital lymphedema, or parasitic infections) or radiation therapy to the breast, skin, or chest wall.42,43 Women with primary angiosarcomas are typically young, in their third to fourth decade, and usually have high-grade tumors with a rapid clinical course.

Postmastectomy angiosarcomas arise in the skin and soft tissues of the arm due to chronic lymphedema after mastectomy and/or radiation therapy.42,43 The etiology of this form of angiosarcoma is likely (1) chronic lymphatic obstruction leading to collateralization and neovascularization that eventually escape tissue control mechanisms or (2) absence of immunologic surveillance as a result of loss of afferent lymphatic circulation.43 These tumors arise from the endothelial lining of lymphatic channels. The majority of angiosarcomas occur within 10 years following mastectomy and typically occur in the upper inner or medial arm. The initial lesion is usually a focal purple discoloration of the skin, which rapidly evolves into plaques and nodules that may ulcerate and bleed easily in the ipsilateral arm, chest wall, or residual breast. These lesions are typically high grade.44

Postradiation angiosarcomas arise in the skin overlying the breast and chest wall and rarely in the breast parenchyma. These tumors typically present in older women (40s-80s), on average 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.42-45 Reddish/blue discolored macules/nodules are identified on the skin within the radiation portals. The majority of lesions are high grade; there is no difference in outcome (disease-free survival or overall survival) when compared to radiation-naïve patients with angiosarcomas.44

Clinically, angiosarcomas may present insidiously, often with a painless discrete mass that grows rapidly and becomes painful.43,46 The typical finding is a bluish-purple-red discoloration of the overlying skin, reflecting the hemorrhage and vascularity of the lesion (Fig. 23-3). Given the aggressive nature of these lesions, the clinical suspicion for an angiosarcoma must be very high. Mammography findings are unrevealing in a third of patients and ultrasound findings are nonspecific.33,43 Breast MRI may demonstrate a mass with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images but high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.33,43 A diagnosis of angiosarcoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology and/or limited biopsy may be difficult.33,46

Figure 23-3

Angiosarcoma. A 90-year-old female with a history of stage IIA invasive ductal carcinoma in 2000, status post segmental mastectomy and negative sentinel lymph node biopsy, radiation therapy, and tamoxifen who developed an angiosarcoma in the radiation field in 2006, which was treated by mastectomy. She developed a recurrent angiosarcoma, shown here with its typical features, in 2007.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree