It is hard to believe that we are only a generation away from the widespread use of the Halstead radical mastectomy. Indeed, breast surgery, as in other areas of surgery, has moved away from more invasive procedures toward minimally invasive techniques. This, coupled with the desire for improved cosmetic outcomes, has been the driving force behind innovation in breast surgery over the last 30 years. The success of the skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) has emboldened surgeons to consider procedures that preserve the nipple and areola as well. Despite the fact that nipple and areola reconstructions generally have excellent satisfaction rates, the nipple remains the cornerstone of breast identity, and evidence of the psychological importance of the nipple-areola complex (NAC) abounds.1 Furthermore, preserving the nipple has the potential to salvage nipple sensation. There is a growing body of evidence on nipple-sparing (NSM) and areola-sparing (ASM) mastectomies. Nevertheless, the topic remains controversial amid concerns about oncologic safety, and there is consensus for neither selection criteria nor technique.

The NSM was first described by Freeman in 1962, who called it the subcutaneous mastectomy. The procedure involved removal of the breast through a submammary or thoracomammary incision while preserving NAC and was recommended for recurrent chronic or subacute mastitis.2 The surgery was plagued by complications, especially flap necrosis, and was eventually abandoned.3 Of note, patients who had the surgery, which removed the breast tissue from an inferior incision, reported a delayed return of sensation to the nipple with permanent loss in many. In 1978, Freeman went on to describe an areola-sparing procedure, called a total glandular mastectomy, for patients with noninvasive cancers.4 A year later Randall et al described an “apple coring” technique for a subcutaneous mastectomy in an effort to improve oncologic safety while preserving as much of the NAC as possible.5 Despite these early efforts, the procedure was abandoned in the proceeding decades amid concerns for oncologic safety.

Central to the debate over the oncologic safety of the NSM is the anatomy of the NAC and the risk of cancer developing in remaining tissue following surgery. Anatomic studies of the areola date back to Morgagni’s work in the 1719. The first thorough description was undertaken by Montgomery in 1837. He described the raised areolar prominences that bear his name and established that lactiferous ducts indeed empty into the areola. In 1980, Smith et al looked at serial sections of Montgomery’s tubercles from 12 mastectomy specimens. They found that the tubercles were associated with lactiferous ducts 97% of the time.6 Of note, they found focal atypia in 2 of the tubercles and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in 1. In 1992, Schnitt et al looked at 8 mastectomy specimens performed for invasive carcinoma.7 They found mammary ducts in the areola of all 8 cases and carcinoma in 2 of them.

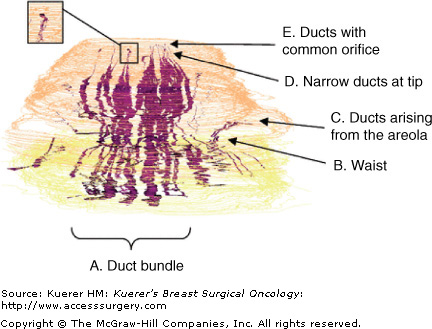

Obviously, the nipple contains the ducts draining the breast parenchyma and this ductal tissue is vulnerable to neoplastic transformation, but recent work has made our understanding more sophisticated. Stolier and Wang looked at nipple cross sections from mastectomy specimens. They found that 9% of mastectomy specimens contained terminal duct lobular units, the origin of most cancers.8 Rusby et al also did nipple cross sections from mastectomy specimens and subjected them to 3-dimensional reconstructions (Fig. 67-1).9 They found that ducts were arranged in a central bundle surrounded by a duct-free rim of tissue. Some of the ducts originated in the areola, but these were morphologically different from ducts forming the central duct bundle, tending to be narrower and without crenellations. They also noted that position of a duct within a nipple did not predict where it terminated in the breast parenchyma. Sections from additional specimens demonstrated that leaving a 2-mm rim of tissue in the nipple papilla excised 96% of the ducts while still leaving 50% of the blood supply.10

Figure 67-1

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the nipple. Skin in tan, cut edge in yellow, and ducts in purple. A. Ducts in a central bundle. B. Bundle narrows to a waist just beneath the skin. C. Some ducts originate in the areola or partway up the nipple. D. Most ducts narrow as they approach the tip of the nipple. E. Many of the ducts originate from a few clefts. [Reproduced, with permission, from Rusby JE, Brachtel EF, Michaelson JS, et al. Breast duct anatomy in the human nipple: three-dimensional patterns and clinical implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(2):171-179.]

Erectile function and sensation of the NAC is dependent upon preservation of the nerve supply. The majority of the nerve supply comes from T4; nerves travel along the chest wall and move medially toward the nipple. There is a secondary supply that originates from the medial T3, emerges lateral to the sternum, and travels to the skin via the lower inner corner of the NAC.11

While few have looked at the anatomy of the areola as a separate entity, even fewer have attempted to identify the risk of cancer of the areola apart from that of the nipple. Simmons et al undertook a retrospective analysis of 217 mastectomy specimens looking for malignant involvement of the nipple, areola, or both by serial sectioning.12 They found that the areola was only involved in 2 of 217 patients (0.9%) and both specimens had large (>5 cm), centrally located tumors. Similar results were published by Banerjee et al, who found areolar involvement in 2 of 219 (0.9%) mastectomy patients.13 Paget disease isolated to the areola is extremely rare, but has been described in the literature.14

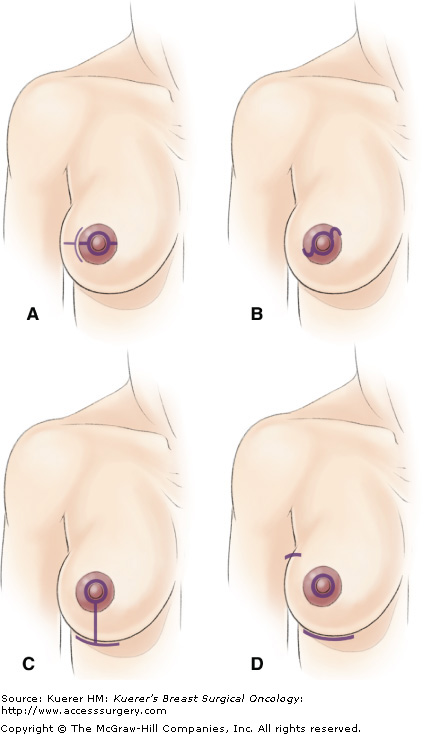

Based on the results of their pathologic analysis of mastectomy specimens, Simmons et al performed ASMs on women for DCIS and small peripheral infiltrating carcinomas, and for prophylactic mastectomy.15 Patients with inflammatory carcinoma, invasive cancer directly beneath the nipple, and locally advanced disease were excluded. One of 4 incisions was used in all cases: tennis racquet, s-shaped, inverted T inframammary crease, or a triple incision (Fig. 67-2). The choice of incision was based upon size of the breast and areola, whether or not a reduction mammoplasty was performed on the opposite breast, and surgeon preference. The procedure resected the nipple, any previous biopsy scar, and all breast parenchyma leaving the areola and a maximum amount of skin for reconstruction immediately to follow. Sentinel node biopsies were performed for patients with carcinoma. A touch prep cytologic evaluation16 of the underside of the areolar flaps was performed on 2 patients with DCIS and microinvasion resulting in negative cytology. Obviously, any gross extension of tumor into the areola or positive touch prep cytology required conversion to a SSM. The flaps were assessed for viability and converted to a SSM if perfusion to the areola was compromised. There were good cosmetic results with no instances of flap necrosis (Fig. 67-3).

Figure 67-2

Schematic representation of incisions used for ASM (small purple line indicates line of incision). A. Linear intra-areola incision with extra-areola extension. B. S-shaped intra-areola incision. C. Inverted-T inframammary crease incision. D. Triple incision with inframammary crease, peri-nipple, and axillary incisions. [Reproduced from Simmons RM, Hollenbeck ST, Latrenta GS. Areola-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(6):547-551.]

Simmons et al published 2-year follow-up on 12 of these patients receiving 17 ASMs with immediate reconstructions.17 Of all the procedures performed, 4 were for DCIS; 3 were for peripherally located, infiltrating carcinomas less than 2 cm; and 10 were for prophylaxis. Patients were followed for complications and recurrence. Ten patients underwent sentinel node biopsy and none were positive. All patients had negative histologic margins. None of the patients had chemotherapy of radiation. Two patients with DCIS and microinvasion underwent intraoperative subareolar touch-prep cytological evaluation with negative results. There was only 1 postoperative complication—a wound infection which resolved with oral antibiotics. With a median of 24 months follow-up, there were no recurrences.

Though the data generated by Simmons et al are compelling, they lack the power to generate a consensus among practitioners. Key to success when performing ASM is patient selection. Simmons et al currently recommend an ASM for prophylaxis, DCIS, and small, peripherally located infiltrating carcinoma, but not for inflammatory carcinoma, invasive cancer directly beneath or involving the NAC, or locally advanced disease. There is no consensus in the literature; additional studies and further follow-up are needed to establish the ASM as the standard of care for a select patient population.

The NSM has long been a temptation for the breast surgeon, with presumed psychological, cosmetic, and functional improvements over the skin-sparing mastectom. These benefits must be carefully weighed against the oncologic safety of the procedure. The topic is hotly debated and a review of the literature is a worthy exercise.

Interest in the risk of malignancy, specifically of the NAC, dates back at least 30 years. Several groups in the 1970s and 1980s looked at serial sections of mastectomy specimens to look for the presence of disease in the NAC. Pathologic evaluation of the NACs revealed involvement in anywhere from 8% to 58%.18 Most of the studies examined nipple sections of consecutive mastectomy specimens and did not exclude patients with clinically evident involvement of the NAC. However, Morimoto et al did exclude patients with tumor directly below the NAC and those with clinically abnormal nipples. They still found nipple involvement in 31% after looking at 141 specimens.19 It is tempting, given the increased surveillance and earlier intervention, to question the applicability of these results to today’s mastectomy patients. However, more recent studies do not indicate that the risk of nipple involvement at the time of surgery is any less than it was 30 years ago.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree