Anatomy

It is important to understand the anatomy of the stomach (in terms of vascular supply, lymphatic drainage, and ligaments) and to be able to recognize these details on cross-sectional imaging, as they constitute important potential pathways of direct spread of gastric cancer.

The primitive foregut from which the stomach develops is connected to the dorsal and ventral abdominal walls via the dorsal and ventral mesogastrium in the embryo.

1,2 During the stomach’s development, the greater curvature and the dorsal mesogastrium grow at a relatively accelerated pace compared with the lesser curvature. This growth and a 180-degree rotation of the bowel along its axis are responsible for the formation of various peritoneal reflections and for the shape of the adult stomach. Embryology of the stomach is described in more detail in

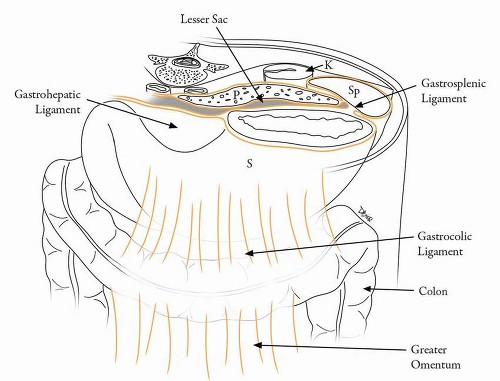

Chapter 1. The gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligaments (lesser omentum) are formed from the ventral mesogastrium. The gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments and the greater omentum are derived from the dorsal mesogastrium (

Table 19-1 and

Fig. 19-1).

1,2Since the stomach develops from the primitive foregut, the blood supply to the stomach is derived predominantly from the branches of the celiac trunk.

3 The arterial supply of the stomach is best visualized on dual-phase computed tomography (CT) imaging of the stomach and consists of the left gastric, right gastric, right gastroepiploic, and left gastroepiploic and short gastric

branches. Recognizing the blood vessels enables the identification of the peritoneal reflections and ligamentous attachments to the stomach.

2 The left gastric artery is a branch of the celiac axis and travels along the gastrohepatic ligament or lesser omentum supplying the lesser curvature of the stomach.

3 The right gastric artery arises from the common hepatic artery and also travels along the gastrohepatic ligament along the distal lesser curvature of the stomach to anastomose with the left gastric artery. The greater curvature of the stomach is supplied by the right and the left gastroepiploic arteries. The right gastroepiploic artery arises from the gastroduodenal artery and traverses the gastrocolic ligament, after briefly traversing the transverse mesocolon. The left gastroepiploic artery arises from the splenic artery and traverses the gastrosplenic and gastrocolic ligaments. The body and the fundus of the stomach are also supplied by short gastric arteries, which are branches of the splenic artery.

3Venous drainage of the stomach accompanies the main arteries. The right gastroepiploic vein drains into the superior mesenteric vein and then into the portal vein. The left gastroepiploic vein drains into the splenic vein and then into the portal vein. The left and right gastric veins drain directly into the portal vein.

3 The shape and position of the stomach vary depending on the volume of gastric contents.

Lymphatic Drainage and Staging Relevance

Lymphatics are numerous and follow the arterial supply of the stomach.

3 The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging as described by the American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) is explained in detail in

Chapter 6 and is based on the number of tumor-involved lymph nodes.

4 N1 disease indicates involvement of 1 to 6 nodes, N2 indicates involvement of 7 to 15 nodes, and N3 disease indicates involvement of >15 nodes.

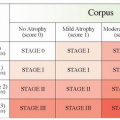

4,5The Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer has classified the regional lymph nodes of the stomach into four major compartments.

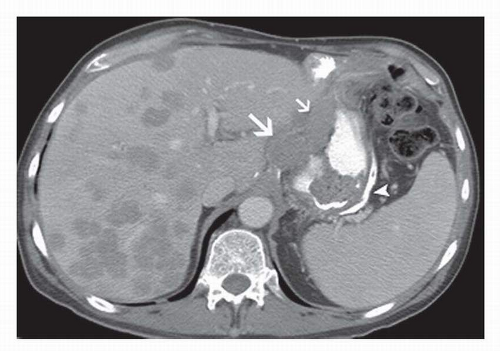

6 Compartment I includes perigastric lymph nodes. Compartment II includes left gastric artery, common hepatic artery, and splenic artery lymph nodes (

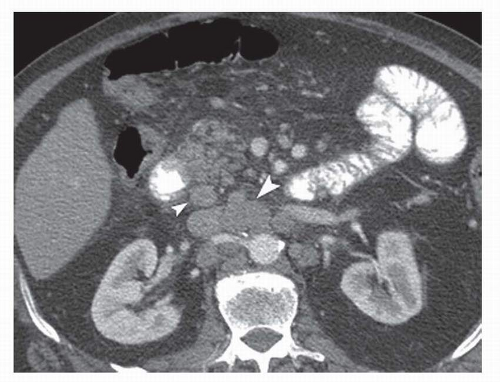

Fig. 19-2). Lymph nodes along the hepatoduodenal ligament, posterior to the head of the pancreas, and at the root of the mesentery comprise compartment III (

Fig. 19-3). Compartment

IV includes lymph nodes along the middle colic vessels and para-aortic lymph nodes (

Fig. 19-3). The D classification or description of extent of lymphadenectomy is based on the extent of nodal dissection (D1-D4) (

Table 19-2).

7A D1 lymph node dissection includes removal of all lymph nodes from compartment I. A D2 dissection includes removal of lymph nodes from compartments I and II, and a D3 dissection includes a D2 dissection and removal of lymph nodes from compartment III. A D4 dissection includes resection of all four compartments.

7The extent of lymph node dissection is a controversial topic.

8 In general, a more extensive dissection is performed in the East such as Japan and Korea. A more conservative approach is followed in the West where studies have shown no increase in survival and instead have seen increased morbidity and mortality associated with extensive lymphatic dissections.

9,10 However, a subgroup analysis showed that in stage 2 and stage 3 gastric cancers, a D2 lymphadenectomy was associated with improved survival when compared with limited D1 lymph node dissection.

10 Patients with D1 dissection also experienced a higher chance of recurrence than did patients with a D2 dissection.

9, 10 and 11 Cuschieri et al.

10 determined that inclusion of splenectomy and partial pancreatectomy was the main reason for the increased postsurgical morbidity and mortality associated with traditional D2 dissection. D3 and D4 lymphadenectomy are practiced mainly in the East, but recent studies have shown no survival benefit in those patients who undergo a more radical dissection.

12 Thus, D2 dissection that spares the spleen and pancreas is currently the accepted standard in several institutions, including The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

13 Therefore, recognition of suspicious lymph nodes in compartments III and IV is very important in the staging of gastric cancer and may have a profound effect on which treatment strategies are used.