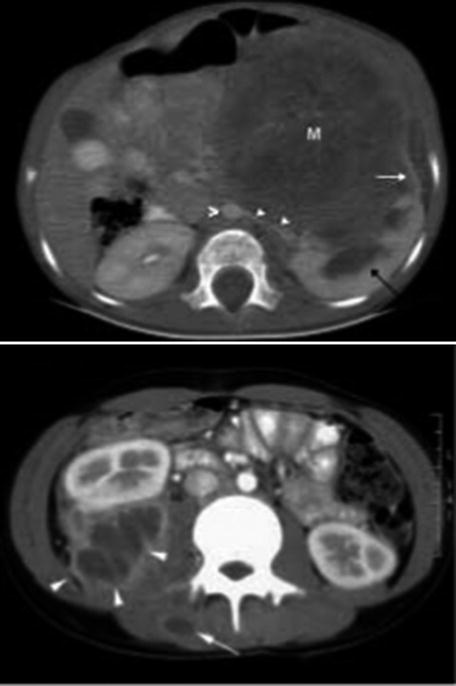

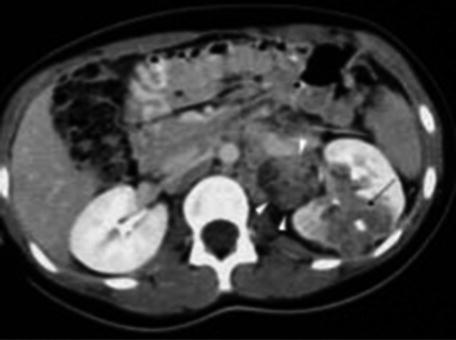

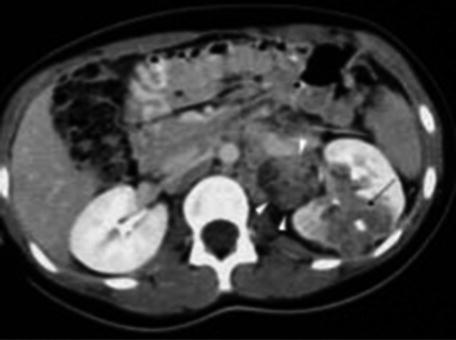

Fig. 24.1

Bilateral nephroblastoma in a 7 year old boy with pulmonary distress

In 90 % of cases nephroblastoma is sporadic, but in 10 % of cases it is associated with congenital anomalies and syndromes [7] (Table 24.1).

Table 24.1

The most common congenital anomalies and syndromes associated with nephroblastoma

Cryptorchidism |

Hypospadia |

Pseudohermaphroditism |

Hemihypertrophy |

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome |

WAGR (Wilms, aniridia, genital anomalies, retardation) syndrome |

Denys–Drash syndrome |

Frasier syndrome |

Perlman syndrome |

Molecular genetic studies of these syndromes led to identification of WT1 gene on the chromosome 11p13, and it is likely that the second gene, WT2, is located close to it, on the chromosome 11p15 [8]. However, only about 1 % of WTs are familial.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Wilms tumor is usually detected incidentally as a large abdominal mass by the patient’s parents or during a physical examination performed for other medical reasons. The mass is usually painless, hard, smooth, and confined to the flank or one side of the abdomen. Other symptoms and signs that may occur include abdominal pain (in approximately 30 % of patients), hematuria (12–25 % of patients), and hypertension (25 % of cases) [1]. No serum markers to diagnose the tumor are used in clinical practice.

Clinical Examination

Once the child is diagnosed with a large abdominal mass, further investigations are needed in order to reach the diagnosis. During the initial clinical examination one should look for possible anomalies associated with nephroblastoma (Fig. 24.2).

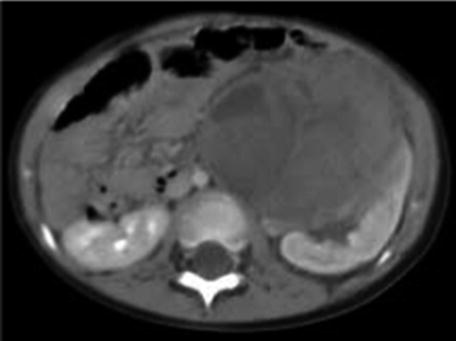

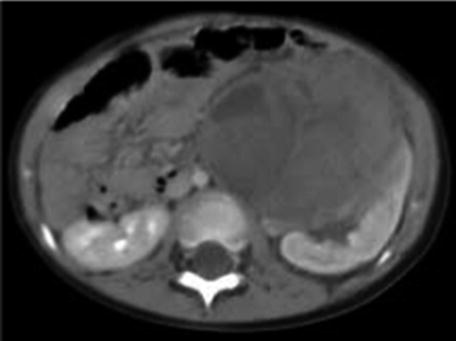

Fig. 24.2

Massive nephroblastoma of the right kidney in a 15 months old girl

It is important to prevent any abdominal trauma by temporarily prohibiting risky activities (jump-bike) and to refer the child as soon as possible to a team specialized in the management of childhood tumors.

This team will confirm the diagnosis by imaging and will complete the staging.

Imaging Studies

There is no laboratory test that can be done in order to diagnose nephroblastoma. Urinary catecholamine metabolites are performed in the differential diagnosis of neuroblastoma; they are normal in nephroblastoma. The preoperative diagnosis of nephroblastoma is based on imaging studies [9] including:

Abdominal ultrasound

Abdominal computed tomography (CT)

Intravenous urography (IVU)

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Abdominal Ultrasound Scan

Abdominal ultrasound scan is adequate for reaching the diagnosis of nephroblastoma in 90 % of cases and it is the first imaging study to be done in any child presenting with an abdominal mass. The tumor is hyperechoic and often shows areas of necrosis. It is important to assess the location of tumor in the kidney and to measure tumor in three dimensions as it is important for assessment of the response to preoperative chemotherapy. Other things that one should look for are the presence of any vascular thrombi, lymphadenopathy, contralateral kidney, and possible hepatic metastases [9].

Abdominal CT Scan

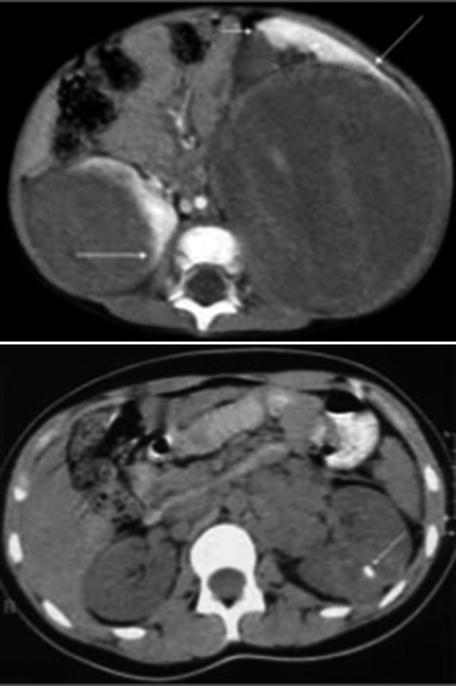

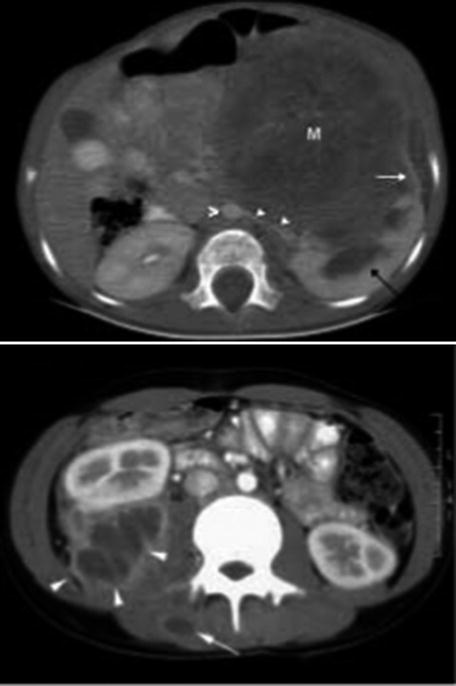

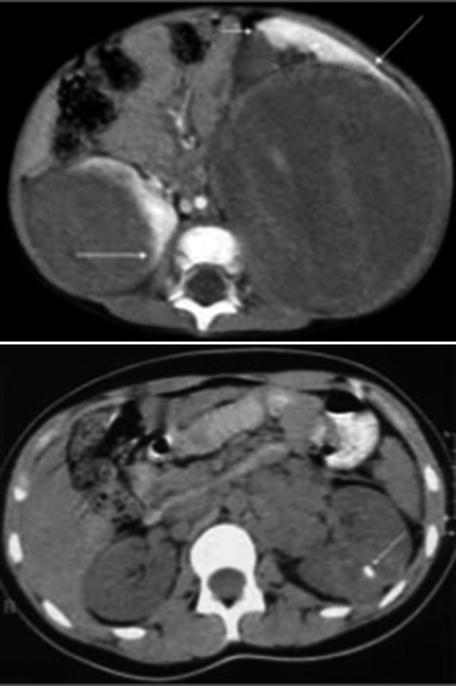

CT scan is only used when the diagnosis is difficult [9] such as in cases when some extrarenal tumors invade the kidney (especially neuroblastoma), in cases of suspected tumor rupture (to assess its extent and intraperitoneal rupture), and in cases of contralateral lesions and suspected liver metastases. A series of images in a child with a nephroblastoma are presented in Fig. 24.3.

Fig. 24.3

Radiology nephroblastoma

Intravenous Urography

This test may be useful when the diagnosis is uncertain. It may show the urinary tract opacification observed in a Wilms tumor (kidney tumor syndrome) with disruption of normal pyelocalyceal architecture that appears stretched, distorted, and amputated. In 5–10 % of cases, the kidney does not show up or excrete very low contrast agent. So it is recommended to increase the dose of contrast agent if the kidney function is normal and also perform a later x-ray.

Abdominal MRI

MRI may aid in the diagnosis of thrombus of the vena cava and it allows verify the possibility of rupture within or behind the peritoneum. Finally, MRI can assess if the other kidney is involved [9].

Differential Diagnosis

Imaging studies are helpful in the differential diagnosis of other tumors, cystic malformations, and hydronephrosis. In the differential diagnosis other retroperitoneal solid masses that should be considered include:

Abscess of the kidney (infectious syndrome).

Renal localization of Burkitt’s lymphoma.

Other retroperitoneal extrarenal tumors in particular neuroblastoma (imposing determination of urinary metabolites, catecholamines), hepatoblastoma, and germ cell tumor (teratoma) which may require measurements of serum level of alpha feto-protein and beta HCG.

Pathology

Gross Pathology

Wilms tumor is usually a large, grossly distorting tumor of the kidney located anywhere within the organ, and very rarely may be even extrarenal. The average weight is about 500 g (300 g after preoperative chemotherapy), but it may range from 60 g to 6.5 kg [5]. The tumor is usually single or rarely multifocal, heterogeneous, often with solid and soft areas due to hemorrhage and/or necrosis, especially in cases treated with preoperative chemotherapy when it may also show a prominent cystic pattern. It may invade renal pelvis, which explains hematuria. Renal vein may be occupied by a tumor thrombus that sometimes grows into the inferior vena cava and reaches the right atrium. Regional lymph nodes are often bulky but are invaded by a tumor only in 15 % of cases [5].

Primarily operated Wilms tumor is a fragile tumor that can rupture and bleed easily and disseminate in the retroperitoneum. If surgery is done following preoperative chemotherapy, tumor’s capsule is much thicker reducing a risk of intraoperative ruptures.

Microscopy

Nephroblastoma is typically composed of different histological components including blastemal, epithelial, and stromal elements which may be represented in any proportion [5, 10]. If none of these components is predominant, tumor is subclassified as triphasic or mixed type, but biphasic or even monophasic type is not rare. The blastemal component may show numerous patterns, and the epithelial and stromal components may show different lines and different degrees of differentiation resulting in innumerable histological patterns. The epithelial component may show primitive epithelial structures such as rosettes, poorly to moderately differentiated tubules, or well-differentiated glomeruli structures. The stromal component may contain a hypocellular, primitive stroma, or a well-differentiated stroma with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, fat and cartilage. Each tumor component may exhibit anaplasia (found in 5–8 % of nephroblastomas) which is defined as the presence of enlarged, atypical, multipolar mitoses, nuclear enlargement, and hyperchromasia. Anaplasia is further classified as focal and diffuse. Preoperative chemotherapy destroys tumor’s components and changes its histological features making histological subclassification more challenging [11]. Histological criteria in the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) and Children’s Oncology Group (COG) classifications differ and should be applied according to preoperative treatment (i.e., if no preoperative chemotherapy was given, the COG criteria should be used [5]; if preoperative chemotherapy was given, the SIOP criteria should be applied) [11]. In both classifications, tumors are stratified into three prognostic groups [5, 12] (Table 24.2).

Table 24.2

The COG and SIOP histological classifications of renal tumors of childhood

COG | SIOP |

|---|---|

Low risk | |

Mesoblastic nephroma | Mesoblastic nephroma |

Cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma (CPDN) | CPDN |

Completely necrotic type | |

Favorable histology | Intermediate risk |

Mixed | Mixed type

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|