Neoplasms of the anus

Bruce D. Minsky, MD  Jose G. Guillem, MD

Jose G. Guillem, MD

Overview

Although an uncommon tumor, the incidence of anal cancer has increased over the past few decades. This increase may be due to sexual transmission of human papillomavirus virus as well as the impact of human immunodeficiency virus. Chemoradiation therapy (CMT) involving pelvic radiation and concurrent chemotherapy (5-FU combined with either mitomycin-C or cisplatin) has resulted in 5-year survival rates of approximately 80% while maintaining sphincter preservation for most patients. Surgery is reserved for selected patients with T1M0 disease who can undergo resection with acceptable functional outcomes or an abdominoperineal resection (APR) for salvage following CMT.

Gross anatomy

There are three regions where anal cancers occur; the perianal skin or anal margin, the anal canal, and the lower rectum. The anal canal is 3–4 cm long and extends from the anal verge to the pelvic floor.1 Cancers of the anal canal and the anal margin have different natural histories. The literature is confusing because of the various definitions of the anal canal and the anal margin. For example, some define the distal limit of the anal canal as the dentate line and all tumors below this as anal margin cancers,2, 3 others consider the distal extent of the anal canal as the anal verge,4, 5 while another definition of anal margin tumors are those tumors that arise within 5 cm of the anal verge.6

The incidence of anal margin and anal canal cancers is dependent on the anatomical boundaries. When the anal verge is defined as the distal margin of the anal canal, 15% of tumors arise from the anal margin, but this number increases to 30% when the dentate line is used as the distal limit. To clarify this issue, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contra le Cancer (UICC) formed a consensus that the anal canal extends from the anorectal ring (dentate line) to the anal verge.7, 8 These two organizations agree that anal margin tumors behave in a similar manner to skin cancers and therefore are classified and treated as skin tumors.

There is an extensive lymphatic system for the anus with many connections. The three main pathways include (1) superiorly from the rectum along the superior hemorrhoidal vessels to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes, (2) from the upper anal canal and superior to the dentate line along the inferior and middle hemorrhoid vessels to the hypogastric lymph nodes, and (3) inferior from the anal margin and anal canal to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Epidemiology

In the United States, cancers of the anal region account for 1–2% of all large bowel cancers and 4% of all anorectal carcinomas. Since 1997, the incidence of carcinoma in situ (CIS) and squamous cell cancer (SCC) anus have dramatically increased. However, more men are more likely to be diagnosed with CIS.9 In 2014, a total of 7210 cases of cancers of the anal region are estimated to occur in the United States, including 2660 men and 4550 women.10 It is estimated that there will be 950 deaths.

Etiology

HPV infection

Squamous cell carcinoma is closely correlated with HPV (human papillomavirus), most commonly types 16 and 18. In a population-based case–control study from Scandinavia of 417 patients with anal canal cancers, a variety of behavioral factors such as sexual activity and venereal infection, tobacco consumption, and anal inflammatory lesions were examined.11 A positive correlation was found by both univariate and multivariate analysis for the number of sexual partners and the risk of anal cancer. An association between venereal infection in both men and women was also noted.

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is rare in heterosexual men, whereas the incidence is 5–30% in men who have sex with men (MSM) who are HIV-negative (human immunodeficiency virus). These changes are rare among HIV-negative women. AIN is linked to HPV and is common in MSM and immunosuppressed patients, especially those who are HIV positive.12, 13 In a report from Surawicz et al.14 of 90 MSM to anal cancer with an abnormal examination of the anal canal, 89% had HPV-associated changes. A recent metatanalysis of 53 trials examining the relationship of HPV infection in MSM revealed that anal HPV and anal SCC precursors were very common.15 The pooled prevalence of HPV-16 was 35% in HIV positive versus 13% in HIV negative patients. However, the rate of progression to cancer was substantially lower than that reported for cervical precancerous lesions.

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)

There is a clear association between HIV and anal canal cancer. Cross-referencing US databases for AIDS with those for cancer, the relative risk of anal cancer in homosexual men compared to men in the general population at the time of or after AIDS diagnosis was 84.1.16 The relative risk of anal cancer for up to 5 years before AIDS diagnosis was 13.9.

Anal canal carcinoma and AIN are associated with condylomata.13 HPV-16 infection has a strong association with high-grade AIN and a risk of anogenital malignancy. However, HPV infection alone may be insufficient for malignant transformation, as many patients with HPV-positive cytology do not develop either AIN or anal cancer.17

Molecular factors

Overexpression of p53 protein has been studied in patients receiving CMT. In an analysis involving approximately 20% of patients entered on both arms of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) protocol 87-04, there was a trend toward adverse outcome (decreased local control and survival) in patients over expressing p53.18 In one study of 55 patients, MIB-1 murine monoclonal antibody measurement of Ki 67 failed to predict outcome for patients treated with radiation, with or without chemotherapy.19 Patel el al proposed that activation of AKT, possibly through the PI3K-AKT pathway, is a component of the development of SCCs.20 In a cohort of 142 Danish patients with SCC of the anal canal treated with CMT, p16 positivity was an independent prognostic factor for disease specific and overall survival.21 Williams et al reported that elevated serum SCC antigen in 174 patients with SCC of the anal margin and canal were associated with a decreased chance of achieving a clinical complete response (cCR), local control, or longer survival.22 Fraunholz reported that EGFR expression correlates with outcome.23 A systematic review of 29 biomarkers in 21 published trials reported that p53 and p21 were the only markers found to be prognostic in more than one trial.24

Other factors

The relationship between anal cancer and fistulas is conflicting. In one study, 41% of anal canal carcinomas were preceded by benign anorectal disease for at least 5 years.25 However, two studies reveal only a temporal relationship but no evidence of causation.26, 27 In a separate study, homosexual males with a history of anal fissure or fistula had an elevated risk of anorectal squamous cell carcinoma (RR, 9.1).28 Overall, the incidence of anal canal cancers in patients with Crohn’s disease is low.29 Immunosupressed renal transplant patients have a 100-fold increase in anogenital tumors compared with the general population.30 In a series of 3595 patients undergoing a solid organ transplant, the incidence of anal cancer was 0.11%.31

Pathology

A variety of histologic cell types may occur in the anal area.32 The majority of these (75–80%) are squamous cell carcinomas33 and 15% are adenocarcinomas. In addition to the more common types seen in Table 1, other rare histologic entities can arise, such as small cell carcinomas35 and lymphoma. Melanomas constitute 1–2% of all anal cancers.36

Table 1 Histologic types of anal cancer

| Type | % |

| Squamous cell | 63 |

| Transitional (cloacogenic) | 23 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 |

| Basal cell | 2 |

| Melanoma | 2 |

| Pagets disease | 2 |

Source: Peters 1983,34 Reproduced with permission of MacMillan Publishing Group.

Squamous tumors may arise from the entire length of the anal canal as well as from the anal margin. Basaloid carcinomas, which are a variant of squamous carcinoma, are commonly referred to as cloacogenic carcinomas. Adenocarcinomas arise from the glands at the dentate line. Small cell carcinomas are of neuroendocrine origin and are rare.

Tumors of the anal margin include squamous carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease (squamous CIS), Paget’s disease (adenocarcinoma in situ), verrucous carcinoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Malignant melanomas may arise from either location but more commonly from below the dentate line.

Squamous cell tumors are divided into those with and without keratinization,37 and nonkeratinizing tumors are further subdivided into basosquamous, basaloid, and cloacogenic carcinomas. With the exception of melanoma and sarcoma, most clinicians conclude that prognosis is more dependent on stage rather than histology and treat all histologic varieties the same.38, 39 In contrast, using a multivariate analysis, Das and associates reported a higher distant metastasis rate for patients with basaloid histologies.40

Studies of flow cytometric analysis are conflicting and have reported both high proliferative index but near-diploid peaks41 as well as an aneuploid pattern.42 In a multivariate analysis by Shepard et al, the depth of penetration, inguinal node involvement, and DNA ploidy were of independent prognostic significance.43

Natural history

The most common route of spread is by local extension proximally to involve other organs in the pelvis. Hematogenous spread occurs more often from tumors that arise at or above the dentate line.44 This pattern of spread allows tumor cells into the portal system resulting in liver and lung metastases in 5–8% of patients44 and bone in 2%.45 Distant metastases occur with equal frequency independent of the histologic cell type involved. Distant metastases are rarely seen with anal margin tumors.

Lymphatic spread is common and involves the inguinal, pelvic, and mesenteric nodes. Inguinal lymph nodes are positive in 15–63% of cases.46, 47 The incidence of synchronous positive inguinal nodes is 15%.44, 48 In a series of 96 patients, Metachronous positive inguinal nodes appeared in 25% with a median time to presentation of 12 months. Pelvic nodes are less commonly involved and mesenteric nodes are more likely to be involved if the tumors are proximal (50%) than distal (14%).49 Positive mesenteric nodes in anal margin tumors are rare.

Historic surgical series report survivals of 0–20% following lymph node dissection with synchronous positive nodes.50, 51 Modern CMT has substantially improved this. Patients who undergo lymph node dissection for metachronous lesions have more favorable survivals with rates as high as 83%.50, 52 The majority of these recurrences occur by 2 years but may present as late as 8 years.49

Diagnosis

The initial and most common symptom is bleeding, which occurs in over 50% of patients. Other common symptoms include pain, tenesmus, pruritus, change in bowel habits, abnormal discharge, and less commonly, inguinal lymphadenopathy.49, 53, 54 Most of these symptoms are associated with benign conditions of the anus including fissure, fistula-in-ano, hemorrhoids, anal pruritus, and anal condyloma. Benign perianal conditions may coexist in 60% of anal margin tumors and in 6% of anal canal tumors.55

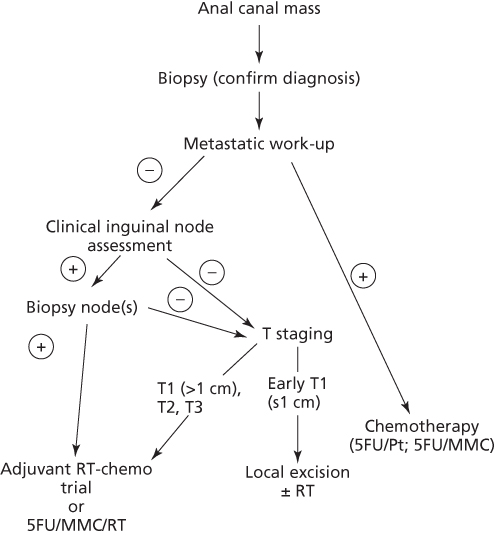

The most common physical finding is an intraluminal mass that can be misdiagnosed as a hemorrhoid.45, 46 Endoscopically, the tumors may appear as flat or slightly raised lesions, as raised lesions with indurated borders, or as polypoid lesions (Figure 1). The use of transrectal ultrasound is required and allows for the determination of depth of penetration and involvement of adjacent organs.56

Figure 1 Treatment schema for squamous cell cancer of the anal canal.

An incisional biopsy is recommended for diagnosis. Excisional biopsies should be limited to small superficial lesions. Clinically palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy should be aspirated for cytological examination. A formal inguinal lymph node dissection is not recommended owing to the associated morbidity, failure to have an impact on outcome, and the high control rates with CMT. In a report by Garcia and associates of 46 HIV+ patients, anal brush cytology was more sensitive and specific for external compared with internal lesions.57 High-resolution anoscopy is helpful in detecting both high-grade intraepithelial and invasive lesions in HIV+58 and HIV− patients.59

Although a metastatic work-up is commonly negative, it includes computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate the primary tumor and exclude liver metastases. A chest X-ray or chest CT is required.

Most studies reveal a benefit of positron emission tomography (PET) for staging.60–63 In a series of 41 patients, 18flourodeoxyuridine glucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) detected 91% of nonexcised primaries compared with 59% with CT alone.64 In addition, 17% of inguinal nodes negative by CT and physical exam were positive by PET. Sveistrup et al.62 performed a retrospective analysis of 28 patients with SCC and found that compared with transrectal ultrasound, PET/CT upstaged disease in 14% and changed the treatment plan in 17%. Bannas et al.65 reported that compared with either PET or CT alone, radiation field design was changed in 23% of patient who underwent a combined PET-CT.

Although feasible, the benefit of sentinel inguinal lymph node biopsy is variable and its role remains controversial.66–68

Staging

A common staging system was developed in 1997 by the AJCC and the UICC. This staging system accounts for the fact that anal canal carcinoma is primarily treated by CMT and abdominoperineal resection (APR) is reserved for treatment failure. The TNM classification is clinical. The primary tumor is assessed for size and for invasion of local structures such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder. The seventh edition of the AJCC staging system is seen in Table 2.69

Table 2 AJCC TNM staging system for anal canal cancer (seventh edition)

| Primary tumor (T) | |||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ | ||

| T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm in maximum diameter | ||

| T2 | Tumor > 2 cm but ≤ 5 cm in maximum diameter | ||

| T3 | Tumor > 5 cm in maximum diameter | ||

| T4 | Tumor of any size, which invades an adjacent structure(s) (involvement of the sphincter muscle(s) alone is not classified as T4) | ||

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| N1 | Perirectal lymph node metastasis | ||

| N2 | Unilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal node metastasis | ||

| N3 | Perirectal and inguinal node, and/or bilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal node metastasis | ||

| Distant metastasis (M) | |||

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | ||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | ||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

| Stage groupings | |||

| Stage | |||

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2–3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| T1–3 | N1 | M0 | |

| IIIB | T4 | N1 | M0 |

| T1–4 | N2–3 | M0 | |

| IV | T1–4 | N0–3 | M1 |

| Note: Anal margin cancers are classified as skin cancers. | |

| Note: Additional descriptors: Although they do not impact the stage grouping, additional prefixes are used, which indicate the need for additional analysis: | |

| Suffix | Reason |

| m | The presence of multiple primary tumors in a single site and is recorded in parenthesis: pT(m)NM |

| y | When classification is performed during or following initial radiation and/or chemotherapy and is based on the amount of tumor present at the time of the examination, and not an estimate of tumor before therapy: ycTNM or ypTNM |

| r | Indicates recurrent tumor: rTNM |

| a | Indicates the stage at autopsy: aTNM |

| Lymphatic vessel invasion (L) | |

| Lx | Cannot be assessed |

| L0 | No lymphatic vessel invasion |

| L1 | Lymphatic vessel invasion present |

| Venous invasion (V) | |

| Vx | Cannot be assessed |

| V0 | No venous Invasion |

| V1 | Microscopic venous Invasion present |

| V2 | Macroscopic venous invasion present |

| Source: Edge 2010.69 Reproduced with permission of Springer. | |

Prognostic factors

As with most gastrointestinal cancers, the most important prognostic factors in anal cancer are T and N stage. In patients treated with radiation with or without chemotherapy, the most striking difference in results is seen when comparing T1-2 primary cancers (≤5 cm) versus T3-4 primary cancers (>5 cm). The local failure rates with T3-4 primary cancers are approximately 50% following CMT. When a complete response is achieved, the local failure rate is 25%.

Peiffert et al.70 reported an increase in local failure with T-stage (T1: 11%, T2: 24%, T3: 45%, and T4: 43%) and a corresponding decrease in 5-year survival (T1: 94%, T2: 79%, T3: 53%, and T4: 19%). A similar decrease in 5-year colostomy-free survival with T1-2 tumors versus T3-4 tumors was reported by Gerard et al.71 (T1: 83% and T2: 89% vs T3: 50% and T4: 54%).

In contrast to T stage, the impact of positive lymph nodes is less clear. Unlike rectal cancer, inguinal lymph nodes in anal cancer are considered nodal (N) metastasis rather than distant (M) metastasis and patients should be treated in a potentially curative manner. Cummings et al reported that patients with negative nodes who received CMT had a higher 5-year cause specific survival compared with those with positive nodes (81% vs 57%).72

The RTOG 87-04 trial (Table 3) reported a higher colostomy rate (which is an indirect measurement of local failure) in N1 versus N0 patients (28% vs 13%).73 In node negative and possibly node positive patients, the addition of mitomycin-C decreased the overall colostomy rates. The EORTC randomized trial (Table 3) of 45 Gy ± 5-FU/mitomycin-C also reported that patients with positive nodes experienced significantly higher local failure (p = 0.035) and lower survival (p = 0.038) rates compared to those with negative nodes.76

Table 3 Randomized trials of combined modality therapy for anal cancer

| Trial | Number of pointts | Initial treatment | Assessment/treatment of residual | Arm | % CR | % With colostomy | % Local crude | Control—actuarial | % CFS | Survival—overall | |

| Intergroup73 | 291 | 45 Gy | Residual | Boost | RT/5-FU | 85 | 22 | — | — | 59 | 70 (4-year) |

| RTOG 8704 | 5-FU | Positivea | 9 Gy +5-FU | * | * | ||||||

| ECOG 1289 | CDDP | RT/5-FU/ | 92 | 9 | — | — | 71 | 75 (4-year) | |||

| Negative | Observe | MMC | |||||||||

| —Vs.— | |||||||||||

| 45 Gy | |||||||||||

| 5-FU/MMC | |||||||||||

| ACT I74, 75 | 585 | 45 Gy | ≥50% CRa | 15–20 Gy EBRT | RT | — | — | 41 | 34 (5-year) | 20 | 33 (5-year) |

| or brachytherapy | * | * | |||||||||

| RT/5-FU/ | — | — | 64 | 59 (5-year) | 30 | 28 (5-year) | |||||

| —Vs.— | <50% CR | Salvage surgery | MMC | ||||||||

| 45 Gy | |||||||||||

| 5-FU/MMC | |||||||||||

| EORTC76 | 110 | 45 Gy | PR/CRa | 15–20 Gy EBRT | RT | 54 | — | 55 | 50 (5-year) | 40 (5-year) | 52 (5-year) |

| or brachytherapy | * | * | * | ||||||||

| —Vs.— | RT/5-FU/ | 80 | — | 73 | 68 (5-year) | 72 (5-year) | 57 (5-year) | ||||

| < PR | Salvage surgery | MMC | |||||||||

| 45 Gy | |||||||||||

| 5-FU/MMC | |||||||||||

| Intergroup77, 78 | 598 | 45 Gy | Positiveb | 10–14 Gy | 5-FU/CDDP | 20 | 26 | 20 | 65 (5-year) | 71 (5-year) | |

| RTOG 98-11 | 5-FU/CDDP | 5-FU/CDDP | * | ||||||||

| ECOG 1289 | or MMC | 5-FU/MMC | — | 10 | 33 | 26 | 74 (5-year) | 78 (5-year) | |||

| Negative | Observe | MMC | |||||||||

| —Vs.— | |||||||||||

| 45 Gy | |||||||||||

| 5-FU/MMC | |||||||||||

| ACT II79 | 940 | 50.4 Gy | — | 5-FU/CDDP 90 | 72 PFS (3-year) | ||||||

| 5-FU/CDDP | |||||||||||

| ± maintenance 5-FU/MMC | 5-FU/MMC 91 | 73 PFS (3-year) | |||||||||

| —Vs.— | |||||||||||

| 50.4 Gy | — | ||||||||||

| 5-FU/MMC | |||||||||||

| ± maintenance 5-FU/MMC |

CFS, Colostomy free survival; *, statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05); MMC, Mitomycin-C; CDDP, cisplatin; LN+, lymph node positive; CR, complete response; PFS, progression free survival; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy. The ACT I trial included 23% anal margin cancers.

a Biopsy at 6 weeks.

b Biopsy at 8 weeks.

Allal et al. reported that, by multivariate analysis, the only variable for which there was a possible impact was overall treatment time (p = 0.09).80 In the EORTC randomized trial, multivariate analysis identified that positive nodes, skin ulceration, and male gender were independent negative prognostic factors for local control and survival.76 Goldman et al.81

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree