NEOPLASMS

CRANIOPHARYNGIOMA

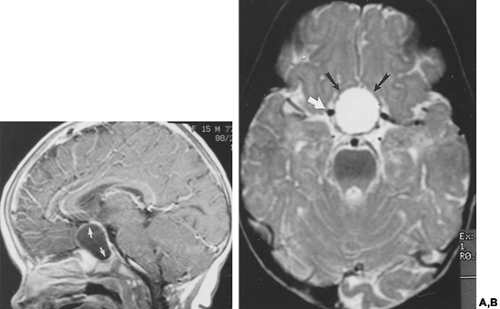

Craniopharyngiomas (Fig. 20-8, Fig. 20-9, Fig. 20-10), which are formed from ectodermal elements of Rathke pouch, are composed of squamous epithelial structures. They can occur anywhere from the floor of the third ventricle (hypothalamus) to the pharyngeal tonsil, with the majority being found in the suprasellar region. These tumors have a bimodal incidence, with peaks in the first and fifth decades of life; they comprise 9% of pediatric brain tumors.19 Clinicopathologically,

two distinct subtypes are recognized: the adamantinous, which tend to occur in children, and the squamous-papillary variants, which tend to occur in adults.20 Craniopharyngiomas may present because of a mass effect on the chiasm, headaches, hydrocephalus, or pituitary and hypothalamic dysfunction.

two distinct subtypes are recognized: the adamantinous, which tend to occur in children, and the squamous-papillary variants, which tend to occur in adults.20 Craniopharyngiomas may present because of a mass effect on the chiasm, headaches, hydrocephalus, or pituitary and hypothalamic dysfunction.

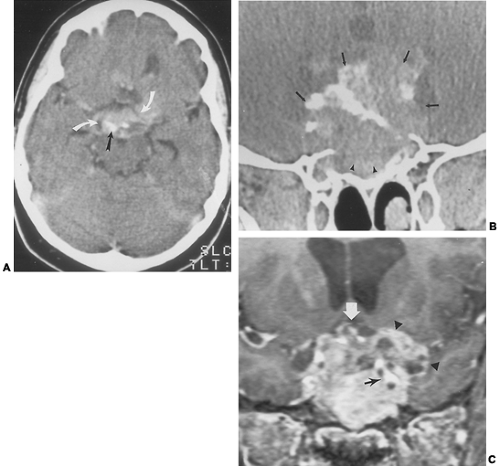

If the lesion is large enough, plain radiographs of the skull demonstrate remodeling of the sella turcica and clinoid processes. The amorphous or curvilinear calcifications, which are present in most pediatric tumors and half of adult tumors, are more readily detected by CT than on plain radiographs.

On CT, craniopharyngiomas can be mixed cystic and solid and often exhibit enhancement of the more solid portions (see Fig. 20-9). Hemorrhage is not an uncommon finding, particularly within cystic portions of the tumors. Most commonly, these tumors are suprasellar in location. Craniopharyngiomas may grow to displace the optic chiasm superiorly, to displace the normal pituitary gland and stalk, to extend into the cavernous sinuses, and even to encase or occlude the carotid arteries.

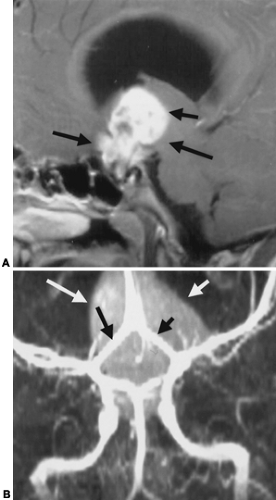

The imaging characteristics of craniopharyngiomas on MRI are variable, reflecting the wide range of components histologically composing these tumors. The tumors may be cystic (see Fig. 20-8), mixed cystic and solid (see Fig. 20-9), or primarily solid (see Fig. 20-10). High signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images is seen in cysts with high cholesterol content or with subacute hemorrhage. Craniopharyngiomas can also be of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images if the cyst contains a large amount of keratin.21 Fluid levels can be seen in cystic regions. Adamantinous craniopharyngiomas tend to be primarily cystic or mixed cystic-solid lesions that occur in children and adults, whereas squamous-papillary subtypes tend to be predominantly solid or mixed solid-cystic and occur in adults. Distinguishing between the two has a prognostic significance, because adamantinous tumors tend to recur. MRI can be helpful in distinguishing between the two: Encasement of vessels, a lobulated shape, and the presence of hyperintense cysts is suggestive of adamantinous tumors; and a round shape, presence of hypointense cysts, and a predominantly solid appearance is seen with squamous-papillary tumors.20 The overall sensitivity for detecting tumor is higher with MRI, and the potential for displaying anatomy in multiple planes provides

excellent data for surgical planning (see Fig. 20-10). Some lesions that can be confused with craniopharyngiomas include arachnoid cysts, dermoid tumors, meningiomas, and aneurysms (if calcified).

excellent data for surgical planning (see Fig. 20-10). Some lesions that can be confused with craniopharyngiomas include arachnoid cysts, dermoid tumors, meningiomas, and aneurysms (if calcified).

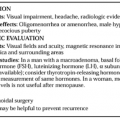

OPTIC CHIASM AND HYPOTHALAMIC GLIOMAS

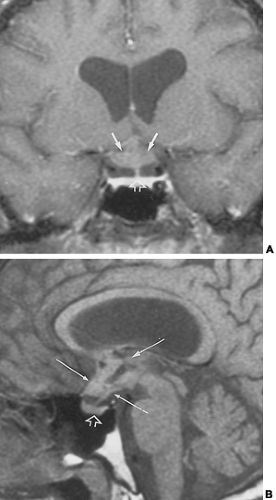

Gliomas involving the optic chiasm and hypothalamus present an imaging problem. It is often difficult or impossible to separate the origin of these tumors because of their intimate association.22 If there is extension of tumor along the optic tracts or optic nerves, it is much easier to determine the site of origin, because there is a characteristic growth pattern for optic pathway gliomas but not for hypothalamic gliomas. Histologically, these gliomas, which are more common in children, are slow-growing pilocytic astrocytomas. Optic gliomas are more common in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (Fig. 20-11). In adults, optic gliomas tend to be more aggressive and usually represent glioblastomas. Usually, plain radiographs are not helpful, except when the tumors extend along the optic nerves

and cause expansion of the optic canals. CT and MRI demonstrate enlargement of the optic chiasm or hypothalamus, which is particularly well seen on coronal images (see Fig. 20-11A). These lesions usually enhance homogeneously with both CT and MRI contrast-enhanced images, and, in the case of optic nerve tumors, there may be extension of abnormal signal and enhancement along the optic tracts and radiations. The differential diagnosis includes craniopharyngiomas, sarcoid, metastases, or lymphomas.

and cause expansion of the optic canals. CT and MRI demonstrate enlargement of the optic chiasm or hypothalamus, which is particularly well seen on coronal images (see Fig. 20-11A). These lesions usually enhance homogeneously with both CT and MRI contrast-enhanced images, and, in the case of optic nerve tumors, there may be extension of abnormal signal and enhancement along the optic tracts and radiations. The differential diagnosis includes craniopharyngiomas, sarcoid, metastases, or lymphomas.

FIGURE 20-11. Hypothalamic and optic pathway glioma. This young man presented with vision problems. He had a history of neurofibromatosis, type 1. A, Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image. The optic chiasm and hypothalamus (solid white arrows) are thickened and globular in configuration. The anterior third ventricular recess is not well seen. The pituitary stalk and pituitary gland (open white arrow) are normal in configuration. B, Sagittal non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image. An irregular mass fills the anterior third ventricle, optic chiasm, and hypothalamic area (long thin white arrows). A segment of the lesion may be cystic and appears as low signal regions. The pituitary gland and infundibulum are normal (open white arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|