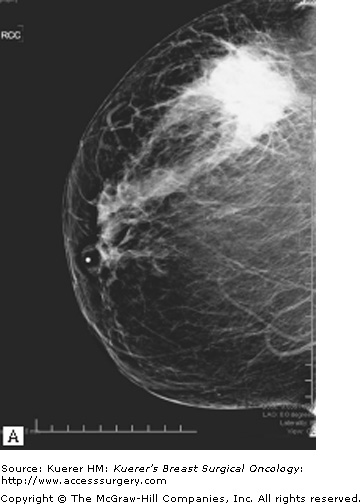

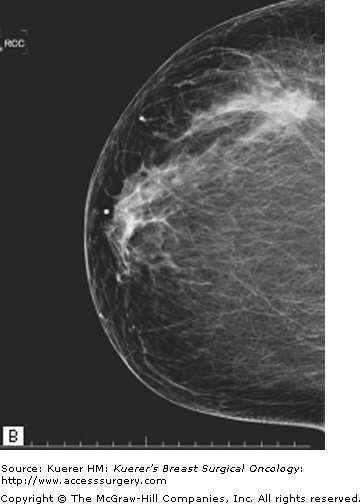

Neoadjuvant (or preoperative) chemotherapy is being increasingly used for the treatment of breast cancer. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy may convert an inoperable breast cancer to an operable tumor. By downsizing the tumor, neoadjuvant chemotherapy also increases the possibility of breast-conserving surgery in a larger number of patients1,2 (Fig. 85-1A). In addition, in patients who have operable breast cancer at the onset, the delivery of neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for excisions of smaller volumes of breast tissue. Indeed, this was shown in a study by Boughey et al3 in which patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy were compared with patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy. For patients who had an initial tumor size greater than 2 cm, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was found to allow for significantly smaller volumes of breast tissue to be excised (113 cm3 vs 213 cm3, p = 0.004). In this study, the delivery of neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not alter the reexcision rate or the number of operations performed in the 2 groups.

Figure 85-1

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for women with operable breast cancer. Comparison of preoperative versus postoperative chemotherapy. A. Locoregional treatment (mastectomy rate). B. Overall survival. C. Disease-free survival. (Reproduced, with permission, from Mieog JS, van der Hage JA, van de Velde CJ. Preoperative chemotherapy for women with operable breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005002.)

Another rationale for neoadjuvant systemic therapy is that this allows for the immediate treatment of micrometastases; however, this has not been associated with an increase in survival in most trials to date (Figs. 85-1B and 85-1C). In contrast, a major advantage is that tumor response to chemotherapy is a strong predictor of outcome. Thus neoadjuvant systemic therapy can be used as an in vivo assay of systemic therapy efficacy. This, in theory, can allow for testing of new therapy regimens in the neoadjuvant setting, allowing for shorter and smaller trials to be conducted using chemotherapy response as the primary end point. In addition, the neoadjuvant setting allows the opportunity to identify biomarkers that can predict response as well as identify pharmacodynamic markers of response, that is to say, markers that can change within the primary tumor with the administration of chemotherapy, which can be an early molecular signal of therapy activity. Although the standard of care at this point has been to not deliver any further therapy in patients who have received a full course of neoadjuvant chemotherapy even if they have significant residual disease, there is now increasing interest in clinical trials of further therapy based on the residual cancer burden, as well as the molecular phenotype of the residual disease for subsequent treatment planning.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy does, however, have potential disadvantages, including loss of pretherapy pathologic staging (tumor size and lymph node status). This raises the potential for both over- and undertreatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Furthermore, neoadjuvant chemotherapy does lead to a delay in local and regional therapy and is associated with a small risk of tumor progression. These disadvantages need to be weighed against the advantages to select the appropriate sequence for surgery and chemotherapy for each patient.

In general, appropriate neoadjuvant regimens mirror the chemotherapy regimens administered in the adjuvant setting. For this reason, the choice of neoadjuvant regimen depends upon the nature of the tumor and patient-centered factors such as comorbidity. Specific regimens are described at length in Chapter 87.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for patients with inflammatory and locally advanced breast cancers. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is indeed necessary before local intervention for inflammatory breast cancer. Locally advanced breast cancer can be further subdivided into several groups. Patients who have internal mammary lymph node involvement (N3B), supraclavicular lymph node involvement (N3C), or chest wall invasion (T4A)4 in general require neoadjuvant chemotherapy to assist in surgical therapy. In contrast, other patients with locally advanced breast cancer may be technically operable at the onset, but neoadjuvant preoperative chemotherapy is still preferred: patients with limited skin involvement (selected T4B), patients with nonfixed matted nodes (selected N2), and patients with limited involvement of infraclavicular lymph nodes (N3A). Patients who have a large tumor compared with their breast size that desire breast-conserving surgery would also benefit from preoperative therapy followed by breast-conserving surgery (Fig. 85-2). An alternative to this approach would be the use of a large wide local excision of the breast with oncoplastic breast remodeling in patients in whom the breast anatomy would allow this approach or breast-conserving surgery with latissimus flap closure to reachieve breast contour. However, neoadjuvant chemotherapy allowing downsizing is usually the initially preferred approach, with consideration of the other 2 surgical techniques to assist in patients in whom chemotherapy does not achieve enough tumor downsizing to allow for breast conservation.

In contrast, there are patients in whom preoperative therapy is undesirable. Patients undergoing preoperative therapy need to have a definitive diagnosis of invasive cancer. Therefore, if a patient has a breast mass, a core biopsy is needed to demonstrate the invasive nature of this tumor rather than a fine-needle aspirate before initiation of chemotherapy. Furthermore, markers for therapeutic planning, including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER-2, need to be obtained on the tumor for proper therapeutic management. In addition, patients in whom the tumor extent is not clear are not good candidates for neoadjuvant therapy. Examples include patients with ill-defined tumor extent on imaging or patients in whom the extent of invasive versus noninvasive cancer is unclear. These scenarios have systemic therapy implications, as chemotherapy may be overtreatment for these patients, and furthermore, it may affect radiation therapy planning. For example, the invasive tumor size (T3 vs not) may affect the ultimate recommendations regarding the need for radiation therapy. If there is no definite need for chemotherapy, surgery first is preferred.

As studies to date have demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy confers neither better nor worse overall survival compared with postoperative therapy (Fig. 85-1B), neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an acceptable alternative to postoperative therapy in any patient who definitely requires chemotherapy. However, this necessitates that there is an experienced multidisciplinary team available, that the tumor response can be closely monitored, and that the patient is compliant. This is preferably done on a clinical trial.

In pretreatment planning, one needs to consider the clinical predictors of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These include treatment regimen–related features, such as the drugs administered, number of cycles delivered, and the therapy schedule. They also include clinicopathologic features, such as tumor size, grade, histologic type, and ER/PR status. Special scenarios to consider include patients with invasive lobular carcinoma histology. Invasive lobular carcinoma is associated with a very low pathologic complete response (pCR) rate (3% for invasive lobular carcinoma vs 15% for invasive ductal carcinoma).5 Also of note, patients who do not have pCR but have lobular histology have a significantly better outcome compared with patients who have residual disease but ductal histology, suggesting that while looking at residual disease for prognostic prediction, one also needs to take histology into consideration. Furthermore, delivery of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for invasive lobular carcinoma has also been shown not to significantly improve the ability to do breast-conserving surgery.6 Taken together, the relative benefit of neoadjuvant therapy with standard chemotherapy seems quite limited for patients with invasive lobular carcinoma.

For ER-positive cancer, there are also relatively low pathologic response rates. Indeed, in the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center series, the pCR rate was 8% for hormone receptor–positive tumors versus 24% in hormone receptor–negative tumors (p > 0.001).7 However, patients with hormone receptor–positive disease who did have pCR had a significant survival benefit compared with those who did not. In spite of the relatively low pCR rates obtained in hormone receptor–positive tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is reasonable for patients with large hormone receptor–positive tumors who desire breast-conserving surgery. However, surgery first is preferred for node-negative patients for whom the need for chemotherapy is unclear. Surgery first would allow for definitive pathology size and nodal status assessment and will allow the patient to participate in the adjuvant therapy trials, such as the Trial Assigning IndividuaLized Options for Treatment (Rx) or the TAILORx trial. Alternative therapy options for these patients include preoperative aromatase inhibitors for postmenopausal patients.

Because of their relatively poor prognosis, patients with triple-negative breast cancer have been of significant interest. Interestingly, patients with triple-negative breast cancer have higher pCR rates than non–triple-negative breast cancer patients (22% vs 11%, p = 0.0034). If pCR is achieved, patients with triple-negative breast cancer have similar overall survival rates as patients with non–triple-negative breast cancer.8 However, if residual disease remains after chemotherapy, triple-negative breast cancer has a worse overall survival rate compared with non–triple-negative breast cancer with residual disease. Thus patients with triple-negative breast cancer may indeed benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy, as they have a significant likelihood of achieving tumor downsizing and pCR. Furthermore, neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows us to identify patients at highest risk for relapse, and these patients may be targeted for clinical trials assessing the role of additional adjuvant therapy for chemoresistant tumors.

The treatment of patients with HER-2-positive disease has recently evolved with the introduction of HER-2-targeted therapies. There have been dozens of clinical trials looking at HER-2-targeted agents in the neoadjuvant setting, with variable responses. One of the most striking responses was seen in a clinical trial conducted by Buzdar et al.9 In this single-institution study conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center, patients with HER-2-positive disease (amplified by fluorescent in situ hybridization or 3+ by immunohistochemistry) were enrolled to receive either paclitaxel followed by fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) or paclitaxel and FEC in combination with the trastuzumab. The clinical trial had a planned sample size of 164 patients but was stopped early after the enrollment of 42 patients based on the clear superiority of the investigational arm. Indeed, the pCR rate was 65.2% in the trastuzumab arm, compared with 26% in the standard chemotherapy arm. This study demonstrated the definitive benefit of anti-HER-2 strategies in achieving pCR. Clearly, this makes the case for anti-HER-2 targeted therapies in the neoadjuvant setting to achieve significant tumor downsizing in this patient population. This also raises the exciting possibility that the multiple evolving targeted therapies can further improve tumor downsizing and pCR rates for other breast cancer subtypes, further improving breast conservation rates.

For successful breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, appropriate patient selection is critical. Large residual tumor size versus breast size, multicentric disease, persistent skin edema, contraindications or unwillingness to receive radiation therapy, and inflammatory breast cancer are considered contraindications for breast-conserving surgery.10 Overall, the indications for breast-conserving surgery are fairly similar to the criteria for breast-conserving surgery de novo.

A prerequisite for successful breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is adequate determination of tumor extent before chemotherapy. Imaging usually includes a bilateral mammography and ultrasonography of the breast, axilla, and infraclavicular, supraclavicular, and internal mammary nodes to identify regional disease. Fine-needle aspiration of any suspicious axillary or supraclavicular lymph nodes is performed for documentation of nodal involvement. There are also evolving data suggesting a role for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for both prediction of response to chemotherapy as well as assessment of tumor response and determination of tumor extent after neoadjuvant therapy. It is important at the onset to biopsy any suspicious lesions in the ipsilateral breast to rule out multicentric disease and in the contralateral breast to rule out bilateral disease before the initiation of systemic therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree