Summary of Key Points

- •

Cancer genomes are characterized by the presence of a variety of alterations including base substitutions, copy-number alterations (amplifications or deletions), and structural rearrangements (translocations or chromosomal rearrangements).

- •

Among the early methods of DNA sequencing (now known as first-generation methods), the most successful has been the Sanger sequencing or chain termination reaction method. Despite its effectiveness, accuracy, and the substantial improvements since its original description, first-generation sequencing has been limited by high cost, labor intensity, and low throughput (amount of data generated per unit of time).

- •

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a broad term describing different technologies characterized by high-throughput, lower cost, and faster sequencing time compared with first-generation methods. NGS enhances the ability to comprehensively identify all alterations in the cancer genome, including mutations, copy-number alterations, and changes in gene expression, in a reasonable time frame.

- •

NGS studies in patients with lung cancer have allowed comprehensive characterization of the molecular alterations in lung adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and small cell carcinomas. These studies have also facilitated the study of the clonal architecture of lung cancer samples and its clinical implications.

- •

It is possible today, with newer technologies, to utilize circulating tumor DNA isolated from peripheral blood or other body fluids of patients for genetic testing. Such testing is less invasive and is becoming increasingly popular in the clinical setting.

The advent of targeted therapies has brought about a paradigm shift in the management of lung cancer. The majority of these drugs, however, only benefit a small subset of patients whose tumors are driven by specific aberrations in cell signaling pathways. Cancer cells demonstrate several types of genomic alterations including base substitutions, copy-number alterations (amplifications or deletions), and structural rearrangements (translocations or chromosomal rearrangements). Point mutations or single base substitutions (also known as single nucleotide variants [SNVs]) represent one of the most common types of DNA alteration. SNVs in protein-coding genes may result in a variety of effects in the resulting proteins. Synonymous mutations alter the DNA sequence of protein-coding genes in a way that the modified sequence at the mutated location still codes for the same amino acid. These mutations are therefore viewed as being “silent,” although recent data suggest that some of these mutations could have important functional consequences. By contrast, missense and nonsense mutations are associated with the substitution of one amino acid for another or premature termination of protein synthesis, respectively. Mutations that arise from the insertion or deletion of one or more nucleotides are referred to as “Indels” (short for insertions and deletions). These mutations can result in frameshift mutations that alter the reading frame of a protein-coding gene. The reading frame of a coding sequence refers to groups of three bases (or codons) in the sequence of a gene, each of which codes for a specific amino acid. When the number of nucleotides inserted or deleted from a coding sequence is not a multiple of three, the reading frame of the coding sequence downstream of the mutation is shifted, resulting in missense or nonsense alterations and the production of an abnormal or nonfunctional protein.

The processing of precursor messenger RNA (mRNA) into mature form occurs through removal of introns and joining of exons in a process termed “splicing.” This process is regulated in cells through proteins that constitute a cell’s splicing machinery. These proteins distinguish introns from exons based on characteristic base sequences within the intron, within the exon, and at intron–exon junctions. Splicing mutations alter these specific sites and deregulate splicing, leading to the abnormal inclusion or exclusion of introns or exons from the final mRNA. This can result in the production of aberrant and nonfunctional proteins. Copy-number alterations are changes in gene number from the two copies present in the normal diploid genome. Rearrangements occur when DNA from one segment is broken and rejoined to a DNA segment from elsewhere in the genome. Rearrangements occurring within the same chromosome or involving regions on different chromosomes are referred to as intrachromosomal or interchromosomal translocations, respectively.

Somatic mutations in cancer cells are identified by comparing the DNA sequence of cancer cells with that of noncancerous “normal” cells acquired from the same individual. Although these somatic mutations occur randomly throughout the genome of a cancer cell, a subset of somatic mutations occurs in a key set of genes that confer growth advantage to the cells harboring them. These “driver” mutations are positively selected during cancer evolution and implicated in oncogenesis. One of the important objectives of cancer genomic studies is to distinguish these driver mutations from bystander “passenger” mutations that do not confer a survival advantage, in an unbiased fashion. This process entails the use of complex statistical algorithms. Apart from offering an insight into the biology underlying malignant transformation, such analyses also facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Overview of Genomic Technologies

First-Generation Sequencing

Among the early methods of DNA sequencing (now known as first-generation methods), the most successful has been the Sanger sequencing or chain termination reaction method. When a dideoxynucleotide triphosphate (ddNTP) is incorporated into a growing oligonucleotide DNA molecule instead of a deoxynucleotide (deoxynucleotide triphosphate [dNTP]), its lack of a 3′-hydroxyl group, which is required for the formation of a phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides, leads to the inhibition of DNA polymerase I and further strand elongation. This chain termination forms the basis of Sanger sequencing. The first step in Sanger sequencing is the preparation of identical single-stranded DNA molecules with a short oligonucleotide annealed to each molecule. This short oligonucleotide helps prime DNA synthesis that is complementary to the single-stranded DNA (template) molecules. Both the DNA template and the primer are incubated with DNA polymerase in the presence of a mixture of the four dNTPs and a small amount of each of the four ddNTPs labeled with radioactive 32-P. Although DNA polymerase does not discriminate between dNTPs and ddNTPs, the considerably larger amount of dNTPs compared with ddNTPs allows the incorporation of several hundred nucleotides before a ddNTP is randomly incorporated into the nascent DNA. Because each reaction is performed with one subtype of ddNTP, the result is a group of nascent DNA molecules of different lengths, but with each ending in a ddNTP. The mixture with each of the ddNTPs is loaded into one of four parallel wells of polyacrylamide slab gel and the molecules are separated according to their molecular mass to allow a deduction of the DNA sequence by visualization of the bands by autoradiography. Because of the relatively easier process and reliability compared with the other technologies, autoradiography has become the method of choice for DNA sequencing. Advances in fluorescent technology allowed the tagging of either the primer or the terminating ddNTP with a specific fluorescent dye and the development of automated sequencing. Four-color fluorescent dyes eventually replaced the radioactive labels and allowed the separation of molecules by capillary electrophoresis, which in turn replaced the slab gel method. One of the advantages of the capillary electrophoresis is that it allows all four reactions to be performed in a single tube.

Despite the effectiveness, high accuracy, and substantial improvements since its original description, first-generation sequencing has been limited by high cost, labor intensity, and time consumed due to the low throughput (defined as amount of data generated per unit of time). Using modern techniques, the automated chain-termination method can involve up to 96 sequencing reactions simultaneously. With each run capable of generating approximately 500 bases of sequence, the 96 sequencing reactions may produce, at most, approximately 48 kilobases (kb) every 2 hours. Although this technology was very useful for sequencing lower organisms, it is not particularly suitable for sequencing the human genome, which is approximately 3 billion base pairs (bp) long.

Next-Generation Sequencing

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a broad term describing different technologies characterized by high-throughput, lower cost, and faster sequencing time compared with first-generation methods. Although the Sanger sequencing method allowed the study of one modality of cancer genomic alterations at a time, NGS enhances the ability to comprehensively identify all alterations, including mutations, copy-number alterations, and changes in gene expression, in a reasonable time frame. NGS is also referred to as massively parallel sequencing, because it allows for a substantial increase in the number of sequence reads simultaneously generated, facilitating higher throughput and leading to considerable cost reduction. Initially, the increased output was achieved with substantial sacrifices in length and accuracy of the individual reads compared with the Sanger sequencing method. Nevertheless, to overcome the higher error rates, NGS platforms use a high level of redundancy or sequence coverage to increase the confidence in base calling. Sequence coverage or depth is the number of times a nucleotide mapped to a genome position is read during the sequencing process, due to overlap of the reads generated during sequencing. Physical coverage is the number of fragments that span a specific location in the genome. A common method to characterize the quality of sequencing reads is the combination of PHRED and PHRAP quality scores, which are algorithms used to evaluate the accuracy of base calling in the raw and assembled sequence, respectively. Both scores correspond to an error probability of 10 – x /10 . Therefore, PHRED or PHRAP quality scores of 20 and 30 correspond to an accuracy of 99% and 99.9%, respectively.

The most common platforms used for NGS are the Roche 454 (Basel, Switzerland), Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA), and SOLiD (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The Roche 454 was the first NGS platform available as a commercial product and uses pyrosequencing, an alternative method of DNA sequencing based on measuring inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) generated during DNA synthesis. In this method, the DNA fragment of interest is hybridized to a sequencing primer and incubated with DNA polymerase, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) sulfurylase, firefly luciferase, and a nucleotide-degrading enzyme. Deoxynucleotides are added in repeated cycles and incorporated into the growing DNA strand at complementary sites of the template strand. During this process, PPi is released in equal molarity to the incorporated deoxynucleotide. ATP sulfurylase catalyzes the conversion of PPi and adenosine phosphosulfate into ATP and sulfate. ATP provides the energy for the oxidation of luciferin into oxyluciferin by luciferase, generating light that can be estimated by a photodiode or charge-coupled device camera. The unincorporated deoxynucleotides are degraded between the cycles by a nucleotide-degrading enzyme, most commonly apyrase. The overall reaction from polymerization to light detection takes approximately 3 seconds to 4 seconds at room temperature. The Illumina platform uses a sequence-by-synthesis (SBS) approach where all four nucleotides, each carrying a base-unique fluorescent label, are added simultaneously to the flow channels together with DNA polymerase and reversible terminators. Each base incorporation step is followed by fluorescent imaging and chemical removal of the terminator. The unique feature of the SOLiD platform is the use of sequencing by ligation, which uses DNA ligase instead of DNA polymerase. The Illumina platform is currently the most widely used platform for NGS.

Applications of Next-Generation Sequencing

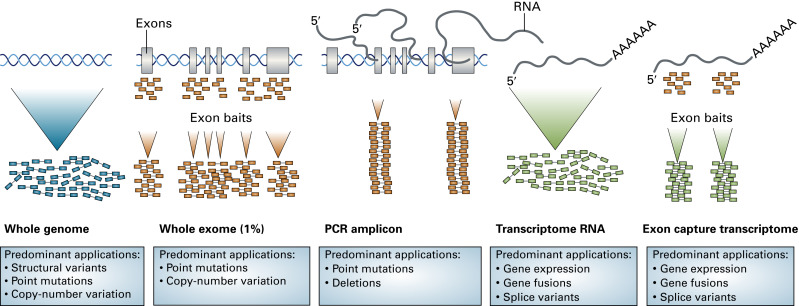

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is the analysis of the entire genomic DNA sequence of a cell at a single time, providing the most comprehensive characterization of the genome. WGS became available after the publication of the Human Genome Project, which generated the reference for human genome sequences. With the use of matched noncancerous genomes, which are usually obtained from skin biopsies in patients with hematologic malignancies and peripheral blood mononuclear cells or adjacent normal tissue in solid tumors for comparison, WGS allows the detection of the full range of genomic alterations as well as noncoding somatic mutations in cancer cells.

The first whole cancer genome sequence was reported in 2008 in a patient with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Using the patient’s skin as the matched normal counterpart, the authors described 10 genes with acquired mutations, including two previously known and eight new mutations. Shortly after that, the initial studies on WGS in lung cancer and other solid tumors were reported. Several tumor samples obtained from patients with various malignancies have been sequenced to date by independent groups and large-scale consortia such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

Whole-Exome and Targeted Gene Sequencing

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and targeted sequencing are alternatives to WGS that allow increased coverage of regions of interest at a lower cost. WES is a process used to evaluate the small percentage of the genome that encodes for proteins. Another approach is the use of cancer-specific gene panels through which only preselected genes are sequenced ( Fig. 11.1 ). Targeted sequencing may be performed using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or NGS. Multiplex PCR entails the simultaneous amplification of two or more DNA targets with unique label probes in a single reaction vessel. Some of the benefits of multiplex PCR include the reduced sample requirements, decreased time, and lower cost compared with singleplex reactions. SNaPshot is one such multiplex PCR platform, in which multiplex PCR is followed by single-base extension reactions that generate allele-specific fluorescently labeled probes designed to test more than 50 hot-spot mutation sites in 14 key cancer genes. With the advances in biotechnology and decreased cost of sequencing, NGS methods are quickly gaining popularity and being routinely employed for targeted sequencing, both in the research setting and in the clinical setting.

Transcriptome

Transcriptome refers to the complete set of mRNA and noncoding RNA (ncRNA) transcripts produced by a cell. One method to characterize the transcriptome is the conversion of mRNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) followed by sequencing of the resulting cDNA library. The subsequent comparison between cDNA and genomic sequences enables the evaluation of actively transcribed regions. Although feasible, this approach with routine full-length cDNA was costly and had low coverage, limiting its use for the characterization of whole transcriptomes in multicellular species. The development of both expressed sequence tag and serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) techniques allowed for substantial advances in transcriptome sequencing methodology. Expressed sequence tags refer to single-pass sequencing reads from either the 3′ or 5′ end of a cDNA clone, which are then used to identify expressed genes. These tags are short and, unlike full-length cDNA sequencing, do not cover the whole length of cDNA. SAGE represented the first sequencing-based method for high-throughput gene expression profiling. SAGE involves the generation of short sequence tags from 3′ ends of mRNA transcripts that are subsequently sequenced and measured to provide estimates of the transcript expression. With the development of NGS platforms, there has been a substantial increase in the throughput and the ability to identify sequence aberrations, alternative splice variants, and ncRNAs through RNA sequencing. ncRNAs are molecules transcribed from genomic DNA but not translated into proteins and include microRNAs, small interfering RNAs, and long ncRNAs. Transcriptome sequencing has also been shown to be a sensitive and efficient approach to detect intragenic fusions in solid tumors.

Epigenome

Epigenome is the complete description of all the chemical modifications to DNA and histone proteins that regulate the expression of genes within the genome. These modifications occur without intrinsic changes in the primary DNA sequence and are necessary for key biologic processes, including differentiation, genomic imprinting of one of the two parental alleles of a gene to ensure monoallelic expression, and silencing of large chromosomal domains such as the X chromosome. The most common mechanisms of epigenetic modification include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and transcription of small ncRNA. In humans, DNA methylation occurs in cytosines that precede guanines (dinucleotide CpGs). CpG-rich regions, also known as CpG islands, are present in approximately 50% to 70% of the 5′-gene promoter regions. DNA methylation of the gene promoter at CpG islands is mediated by DNA methyltransferases, which leads to silencing by direct inhibition of transcription factor binding to their relative sites and recruitment of methyl-binding domain proteins. Cancer cells frequently display global hypomethylation, which is found within the body of genes and regions flanking the genes, and CpG island promoter-specific hypermethylation. Whereas global hypomethylation accounts for the activation of proto-oncogenes and loss of imprinting, promoter hypermethylation is associated with decreased gene expression, leading to an alternative way of silencing key tumor suppressor genes. Epigenetic modifications have been implicated in conferring the second hit for cancer initiation by silencing the remaining active alleles of a previously mutated tumor suppressor gene. Posttranslational histone modifications occur mainly at the N -terminal tails of histones and are mediated by several enzymes, including histone methyltransferases and demethylases, which introduce and remove methyl groups, respectively, and acetyltransferases and deacetylases, which introduce and remove acetyl groups, respectively. The various combinations of modifications in specific genomic regions lead to changes in the chromatin structure with activation or repression of gene expression.

The three most common techniques for the evaluation of DNA methylation are the digestion of genomic DNA with methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes, affinity-based enrichment of methylated DNA fragments, and chemical conversion methods. The standard method for mapping DNA methylation is bisulfite sequencing, a chemical conversion method. Treatment of genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite chemically converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil. Assuming a near-complete bisulfite conversion, all unmethylated cytosines become thymidines after PCR and the remaining cytosines are the ones methylated at the fifth carbon or 5-methylcytosine.

Comprehensive Genomic Studies Using NGS in Lung Cancer

Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer

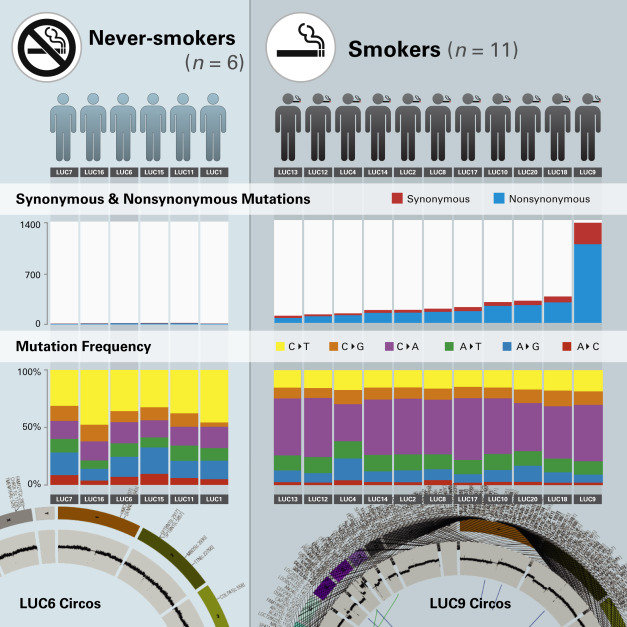

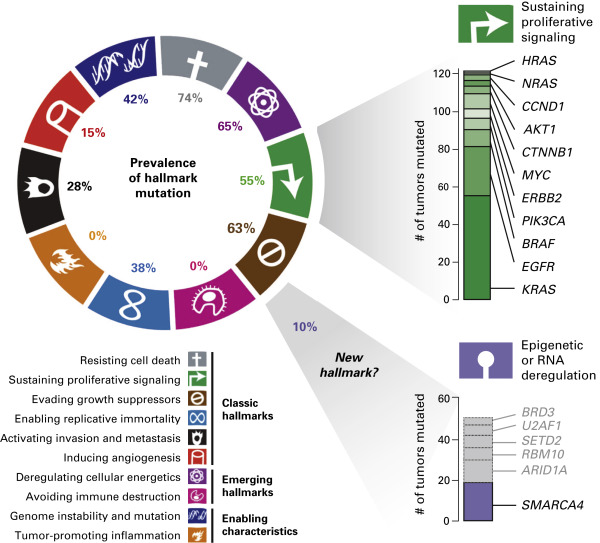

Multiple independent groups and TCGA research network have together sequenced over a thousand lung cancer samples to date. Data from these studies indicate that recurrent alterations in known receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-RAS (RAt sarcoma)-rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) pathway genes such as EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, MET , and ALK are observed in the majority of lung adenocarcinoma genomes. Nearly 76% of lung adenocarcinomas showed alterations in this pathway in a recent analysis including 660 tumor samples. Although tumors obtained from both smokers and never-smokers show alterations in the RTK pathway genes, cancers arising in these populations differ in other aspects such as mutational burden and pattern of SNVs, and also show enrichment for alterations in specific genes. The exonic mutation rates are significantly higher in smokers than in never-smokers (median, 9.8 vs. 1.7 per megabase [Mb], p = 3 × 10 –9 ), with the predominant mutation patterns being C-to-T transitions and C-to-A transversions in never-smoker and smoker lung cancer genomes, respectively ( Fig. 11.2 ). In addition to mutations in RTK-RAS-RAF signaling, lung adenocarcinomas also show alterations in tumor suppressors such as TP53, CDKN2A, STK11 , and NF1 . Furthermore, adenocarcinomas also show recurrent alterations in genes involved in epigenetic or RNA deregulation such as BRD3, SETD2 , and ARID1A, and genes that regulate splicing such as U2AF1, RBM10 , and SF3B1 . Alterations in these genes possibly drive malignant transformation by altering the splicing of oncogenes such as CTNNB1 . Because genes involved in epigenetic or RNA deregulation cannot be readily assigned to one of the 10 hallmarks of cancer that were originally described, these data suggest that such alterations could constitute the 11th hallmark ( Fig. 11.3 ).

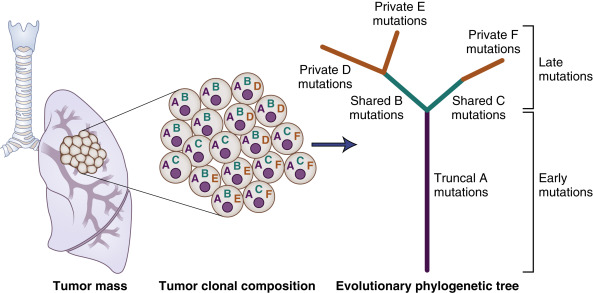

In addition to the identification of recurrent pathway alterations, NGS also has the ability to identify potential targets for therapy. For instance, TCGA investigators reported alterations in cellular pathways known to be potentially targetable, such as phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT and RTK-RAS-RAF, in nearly 75% of lung adenocarcinomas and 69% of squamous cell carcinomas. Targeted sequencing with a high-read coverage can also help in the estimation of variant allele frequencies, based on the distribution of which, it is possible to infer the number and size of clonal populations within each tumor sample. Using these techniques, several groups have described the clonal architecture of lung adenocarcinomas. These analyses indicate that lung cancers show a considerable extent of intratumor heterogeneity ( Fig. 11.4 ).

Founder clone mutations refer to those mutations that are present ubiquitously within all tumors cells, implying that they are acquired early on in the course of disease evolution. In one analysis, Zhang et al. observed that on average 76% of all mutations observed through multiregion sequencing of adenocarcinoma samples were present in all regions of the tumor. Alterations (mutations) in known cancer genes such as TP53 , EGFR, and KRAS were ubiquitous, suggesting early acquisition. Understanding the clonal architecture of tumors has, in theory, the ability to guide therapy because treatments that target clonal alterations are more likely to succeed than those that target subclonal alterations.

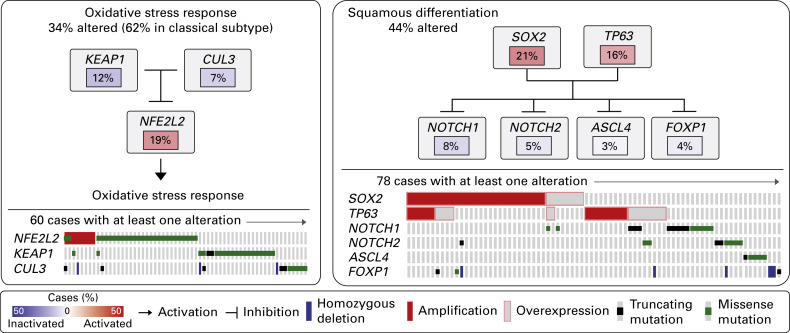

TCGA investigators initially profiled tumor specimens from 178 patients with squamous cell lung cancer, along with peripheral blood (41 patients) or adjacent histologic normal tissues resected at the time of surgery (137 patients) as the matched noncancerous germline DNA. Samples from all 178 patients were evaluated with WES, RNA sequencing, DNA methylation, and copy-number evaluation, whereas 18 paired samples were evaluated with WGS and 158 paired samples were evaluated with microRNA sequencing. WES and WGS were performed with the Illumina HiSeq platform. As observed in lung adenocarcinoma from smokers, the investigators identified a mean of 228 nonsilent exonic mutations per tumor (mean somatic mutation rate of 8.1 per Mb) in these tumors. Somatic alterations of potentially targetable genes were found in 114 (64%) samples. The most commonly altered pathways were the PI3K-RTK-RAS signaling (69%); squamous differentiation, including SOX2, TP53, NOTCH1, NOTCH2, ASCL4 , and FOXP1 (44%); and the oxidative stress response pathway consisting of KEAP1, CUL3 , and NFE2L2 (34%; Fig. 11.5 ). The CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene was inactivated in 72% of the cases by a variety of mechanisms, including homozygous deletion (29%), epigenetic silencing by methylation (21%), inactivating mutation (18%), and exon 1-beta skipping (4%).