Major Concepts

Outbreaks

Monkeypox is a zoonotic infection that occurs in several species of nonhuman primates and African rodents. Its natural reservoir is believed to be the rope squirrel. This disease was first noted in humans in 1970 in parts of Central Africa, particularly the Congo River basin, where it affected hundreds of people. It was later found to occur much less commonly in West Africa. In 2003, monkeypox entered the United States in a shipment containing infected West African rodents. The ill animals were housed in close proximity to prairie dogs, which became infected prior to their distribution as pets in several states in the Midwest. At least 37 persons became infected through contact with these animals and another 32 suspected cases were reported.

Symptoms

Monkeypox in humans is characterized by a smallpoxlike rash and lymphadenopathy. The causative agent is the monkeypox virus, an orthopoxvirus. The Orthopoxvirus genus is a group of large, double-stranded DNA viruses that include variola, vaccinia, cowpox virus, and buffalopox virus. Monkypox virus shares 85% DNA sequence homology with variola. Two distinctive forms of the disease have been reported. The first and more common form is found in humid lowland forests of Central Africa. This form generally has higher numbers of skin lesions than the second form. It has a case fatality rate of 10% to 16% and a moderate potential for transmission between humans, although at a rate lower than that seen for smallpox. The form of disease reported in West Africa and the United States is typically milder, with fewer lesions and a much lower mortality rate. It is also rarely transmitted through human-to-human contact. Genetic analysis of isolates of the monkeypox virus from Central Africa and the United States has led to their placement into two distinct clades.

Immune Response

Neutralizing antibodies play an important role in host defense against this illness. The monkeypox virus, in response, employs several mechanisms to evade both the adaptive and innate immune responses. These include the ability to block activation of CD4+ T helper cells and CD8+ T killer cells, blocking simulation of natural killer cells by producing a competitive inhibitor of the cell’s activating receptor, and blocking binding of key cytokines involved in monocyte migration.

Diagnosis

Antigenic similarities between monkeypox virus and other more common poxviruses, such as varicella, make definitive diagnosis by serological means difficult. More sensitive and specific PCR and ELISA assays have recently been developed, however.

Protection

Treatment of monkeypox is often primarily supportive, although several antiviral compounds, including cidovir and ribavirin, are being developed or tested for use in humans with this disease. Prior immunization with vaccinia results in lower disease incidence and severity for those infected with the Central African–type virus. The risk of serious complications following vaccination, especially in regions with a high incidence of HIV-positive individuals, however, dictates against its routine use, even in endemic regions. Several promising vaccine candidates are being produced. These are highly attenuated vaccinia derivatives that provide rapid protection in nonhuman primate models and have good safety profiles in human testing.

Smallpox (caused by the variola orthopoxvirus) was a dreaded disease throughout most of human history, resulting in great loss of life and often permanently disfiguring the survivors. Due to a heroic effort, this killer was eradicated from the natural world by an extensive campaign that concluded in the 1970s. One of the cornerstones of this campaign was large-scale immunization with vaccinia, another orthopoxvirus, which provided a high degree of cross-protection. Routine vaccination was then halted due to the high potential for development of serious complications, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

After the elimination of smallpox and as a result of the heightened awareness of pox-forming diseases, human monkeypox infections were detected in parts of Central and occasionally West Africa in small villages located in the humid lowland areas. It was later determined that prior immunization with vaccinia protected humans against monkeypox virus infection and that vaccinated persons had less severe illness. As time has passed since vaccinia immunization ended and more and more people go unvaccinated, the incidence of human monkeypox cases has risen. In 2003, the importation of West African rodents into the United States led to the infection of prairie dogs housed in the same facility. Some of these animals subsequently infected humans in the Midwest. The clinical manifestations and transmission patterns of the Central African and West African and U.S. forms of monkeypox differ in several respects, leading to their separation into two separate clades that also differ genetically. The potential for serious disease and death from monkeypox, especially the Central African form, and the potential for its use in bioterrorism make surveillance for this disease a matter of great importance.

Monkeypox virus was first reported in 1958 as the causative agent of smallpox-type rash in cynomolgus macaques housed in a colony in Denmark. Nine instances of outbreaks of monkeypox were reported in similar colonies of nonhuman primates and in a zoo between 1958 and 1968. Six of the nine outbreaks occurred in the United States. A variety of species of monkeys and great apes were involved, including cynomolgus, rhesus, and pigtailed macaques; African green monkeys; squirrel monkeys; langurs; marmosets; orangutans; gibbons; gorillas; and chimpanzees. An anteater was also infected after close contact with an infected primate. The affected species of primates naturally occur in Africa, Asia, and South America. The index animals in the outbreaks originated in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, India, and Sierra Leone. Persons having close contact with the animals during these events, including their handlers, did not appear to contract the disease. No serological evidence of infection was detected at this time in other animals from Chad, India, Kenya, Mali, or Upper Volta.

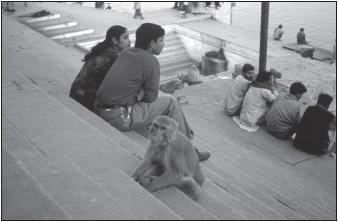

FIGURE 23.1 Humans and nonhuman primates share living space in many countries in Africa and Asia

Source: CDC/Chris Zahniser.

Monkeypox was first recognized in humans in 1970, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; formerly Zaire) in Central Africa. Smallpox had once been widespread in the region but had been absent from the area for two years. Given the similarities in presentation between these two diseases, it is likely that human infections with monkeypox had been present in the area for some time and had been misdiagnosed as smallpox. Between 1970 and 1979, some 54 cases of monkeypox in humans were reported in tropical rain forest regions of seven countries in Central Africa, particularly the Congo River basin, and less commonly, in West Africa. The DRC had the overwhelming majority of these cases. Prior to 1980, studies of monkeypox were performed during the campaign to eradicate smallpox or to confirm the success of the eradication efforts. Vaccination against smallpox with vaccinia also produced a high degree of protection against monkeypox and decreased the severity of disease in individuals who did become infected. After the elimination of natural transmission of smallpox in 1980, monkeypox surveillance in the DRC was increased, resulting in the detection of 350 human cases. Small numbers of infections were also reported in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire), Liberia, Nigeria, Congo Republic, and Sierra Leone. Secondary transmission of the disease between humans was also reported in the DRC.

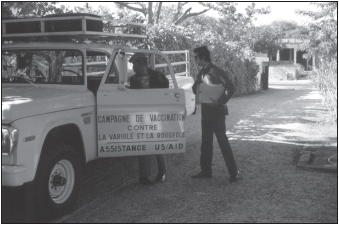

FIGURE 23.2 Vaccination with vaccinia virus during the smallpox eradication program of the 1970s in West Africa

Source: CDC/Jean Roy.

The number of reported cases of monkeypox dropped dramatically between 1987 and 1995 (14 cases total) and then rose after 1996, with several outbreaks involving over 500 suspected cases occurring over the next three or four years. One village was especially hard hit, with 12% of the population becoming ill. The war in DRC as well as the termination of routine smallpox vaccination may have been factors in the increased disease incidence, as the majority of infected individuals were under the age of 25 years and unvaccinated. Many cases in 1997 had serological evidence of recent or past exposure to varicella-zoster virus. Coinfection with HIV was not common.

In 1998 and 1999, several hundred suspected cases of monkeypox were reported. Definitive diagnosis was not made in the majority of these cases due to military battles, civil unrest, and security issues in the region, which is a major diamond-mining area. The cases during these outbreaks differed in several respects from the previously confirmed cases: the large number of cases, an increased incidence of secondary spread between humans (estimated at 88%), and decreased clinical severity with a lower mortality rate (1%). These differences suggest either misdiagnosis (confusion with chickenpox) or a change in the character of the circulating strains of the monkeypox virus. In cases for which a definite diagnosis was possible, 75% of the rashes resulted from monkeypox and the remaining 25% were chickenpox.

Monkeypox entered the United States in April 2003 in a shipment of six types of African rodents imported into Texas. Seventy-two persons (37 laboratory-confirmed cases and 35 meeting the case definition) were infected in Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin. The origin of this outbreak was traced to close contact with black-tailed prairie dogs, including animals in a household day care facility. Increased length or extent of exposure to the prairie dogs was associated with greater risk of acquiring illness. Of the 11 persons initially infected, many had been scratched or bitten by the rodents. None of these individuals died, and in the majority (80% to 90%), the disease severity as ascertained by the number of rash lesions was minimal (1 to 50 lesions), even though more than half of the infected had no prior history of vaccinia vaccination including one child under the age of 5 years. In contrast to prior infections in Africa, vaccination did not appear to diminish disease severity, and few overall symptomatic differences were noted between pediatric and adult patients, although two children were admitted to intensive care units with encephalitis or retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy and abscess. Unlike the reports of infection in Africa, no human-to-human transmission of overt disease was reported in the U.S. outbreak, although subclinical illness may have occurred in three persons previously vaccinated.

The distributor of the infected prairie dogs in Illinois had housed an infected giant Gambian pouched rat from a shipment of animals originating in Ghana. Rope squirrels and African dormice from the shipment were also infected. The prairie dogs appear to have been the source of the human infections; virus was found in their skin, eyelids, tongues, respiratory systems, and mucosal secretions. Gambian rats have now gained a foothold in the Florida Keys. North American ground squirrels are also susceptible to infection. The viral strain involved in this outbreak bore genetic similarity to that previously found in primate colonies in West Africa and differed from strains originating in the DRC.

An outbreak involving 11 cases occurred in Congo Republic in Central Africa at the same time as the one in the United States, but the two outbreaks were quite different. One remarkable aspect of the infection in the Congo was that it resulted in seven rounds of human-to-human transmission, longer than previous instances in the DRC. The mortality rate was 10%, and disease was severe (more than 200 lesions) in a third of the cases. Most of the infected persons had an association with a hospital or lived in its vicinity.

Monkeypox leads to a papulovesicular eruption in humans. Other infectious diseases characterized by this type of skin lesion include viral infections, such as smallpox (variola virus); chickenpox and shingles (varicella-zoster virus); hand, foot, and mouth disease (Coxsackie virus); atypical measles (rubella); eczema herpeticum (herpes simplex virus); and rickettsialpox (Rickettsia akari), as well as bacterial infections, such as yaws (Treponema pallidum) and impetigo (group A streptococci).

Initially, infection with the monkeypox virus (Central African type) results in microbial uptake by regional lymph nodes, followed by viral replication in lymphoid organs and viremia from 3 to 14 days postinfection. Early symptoms include fever, headache, backache, and fatigue. During the second week, skin eruptions begin to appear, evolving from macular (flat) to papular (palpable) to vesicular (fluid-filled) to pustular (pus-filled) lesions that crust and then scar during the 8 to 23 days following infection. These generalized skin lesions are in the same stage of development and have a centrifugal distribution

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree