Major Concepts

Incidence

The first known Cryptosporidium species was discovered in mice in 1907, but these parasitic protozoa were not detected in humans until 1976. Very few human infections were noted over the next few years until the organisms were linked to a serious diarrheal condition in HIV-positive men during the early 1980s. Since then, Cryptosporidium species have caused disease in diverse populations, including very young children, the elderly, persons in developing regions, campers and backpackers, people coming into contact with farm animals, and immunosuppressed individuals. Infection in this last group is often chronic, severe, and potentially life-threatening. Immunocompetent people may become ill as well. Several large outbreaks have occurred in industrialized nations, including the United States and Canada, due to waterborne transmission. The largest outbreak occurred in 1993 in Milwaukee and affected more than 400,000 people.

Symptoms

Most Cryptosporidium species that infect humans cause diarrhea. One species, however, causes fever, generalized malaise, nausea and vomiting, malnutrition, significant weight loss, and delayed growth. Infection of the intestine leads to blunting of villi and increased levels of transitional epithelium. This may result in malnutrition, altered absorption and secretion of sodium and chloride ions, and dehydration due to the loss of large amounts of water in the stools.

Infection

Cryptosporidiosis is caused primarily by either C. hominis or C. parvum, which closely resemble each other morphologically but differ genetically, in clinical presentation, and in host range. Infection with C. hominis is mainly restricted to humans and may cause serious disease. This parasite is most likely to be involved in large outbreaks due to contamination of either drinking or recreational water sources. C. parvum infects humans, calves, sheep, goats, and deer and may cause isolated cases by zoonotic transmission. It generally causes a milder form of disease than C. hominis. Both species are members of the Apicomplexa protozoan phylum. They have several life stages, including hardy oocysts released into the feces, motile sporozoites and merozoites, and sexual forms.

Immune Response

Cryptosporidium infection stimulates the production of chemokines, which attract cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems to the intestinal lamina propria. Cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 are released into the area. Th1 CD4+ T helper cells, IgG, and IgM are particularly important in resolving infection. Long-lasting immunity is not produced, however, and individuals are often reinfected.

Protection

Many drugs have been tested for the treatment of Cryptosporidium infection, without much success due to difficulty in accessing parasites located under the mucosal epithelium or within dense attachment complexes. Nitazoxanide is currently recommended to treat cryptosporidiosis in healthy persons over the age of 12 months, but it does not completely eliminate infection in all persons. Antiviral therapy given to HIV-positive individuals increases CD4+ T cell numbers and helps resolve infection. Oral or intravenous rehydration therapy is useful to counteract water loss. Prevention involves decreasing ingestion of viable oocysts from fecal material. Oocysts are highly resistant to chlorination and pass through many filters. Persons with diarrhea should avoid using recreational water and preparing food. Fruits and vegetables that will not be cooked should be washed thoroughly with soap and clean water. Travelers, campers, and backpackers need to ensure the safety of their water supplies.

Since the advent of the AIDS epidemic, a number of organisms have been identified that are responsible for serious or life-threatening infections in immunosuppressed persons. These include agents that cause respiratory illnesses, diarrheal disease, and unusual cancers. Some of these agents were later found to be pathogenic in immunocompetent individuals as well, particularly young children. Organisms that cause severe diarrhea in humans include Cyclospora, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium species. Several groups of the protozoan genus Cryptosporidium infect humans, the two major species being C. hominis and C. parvum. Infection with the former primarily occurs in humans and may result in severe illness, including fever, vomiting, dehydration, malnutrition, and growth deficiency. C. parvum infects a number of ruminants, including calves, sheep, and goats, in addition to humans and may be acquired via zoonotic transmission (transmission from animals to humans). Infection with this protozoan typically leads only to diarrhea.

Inhabitants of developing nations are far more likely to acquire infection than those living in developed regions. Children in developing areas are usually infected very early in life. Infection causes alterations of cells in the intestinal wall that interfere with the absorption of nutrients. Infected children may suffer long-term consequences, such as stunted growth, from the resulting malnutrition. Immunosuppressed individuals, especially those with low CD4+ T helper cell numbers, often develop chronic, life-threatening disease. They should take particular care to avoid infection. Transmission may occur in a variety of manners, including via contaminated drinking water or recreational water, such as lakes, swimming pools, water slides, and hot tubs. Cryptosporidium parasites are highly resistant to chlorine, and their small size presents difficulties in removing them from drinking supplies by filtration. A major epidemic occurred in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that sickened more than 400,000 persons and was particularly dangerous to HIV-positive individuals. Other outbreaks in industrialized nations, including the United States and Canada, have involved imported foods.

Cryptosporidium muris was discovered in the gastric glands of asymptomatic mice in 1907 by Edward Tyzzer, who later identified C. parvum in the small intestine of these rodents in 1912. Infection by various other Cryptosporidium species was linked to diarrheal disease in poultry, calves, and several other animals since the 1950s. In 1976, a 3-year-old child was found to be infected with Cryptosporidium; seven more human cases were reported over the next six years, five of which occurred in immunocompromised persons. These organisms were not widely recognized as human pathogens, however, until the advent of the AIDS epidemic starting around 1982. In 2002, the genus was divided into two primary species infecting humans, Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis. These enteric (gut-associated) pathogens are two of several protozoa found to cause severe, persistent diarrhea that is life-threatening in HIV-positive individuals. The genus was subsequently discovered to lead to endemic persistent diarrhea in normal, healthy adults residing in tropical regions as well.

A large outbreak involving drinking water occurred in Milwaukee in 1993 and a smaller one in Las Vegas in 1996. The Milwaukee outbreak was unusually severe and involved 403,000 people. It was the largest waterborne infection in U.S. history and is believed to have cost $96.2 million: $31.7 million in medical costs and $64.6 million in lost productivity. The Las Vegas outbreak occurred in spite of a state-of-the-art water treatment facility and was detected only because Cryptosporidium infection is a reportable illness in Nevada. In 2007, more than 1,900 cases of cryptosporidiosis were reported in Utah. This outbreak was linked to recreational water use in pools, water parks, and interactive fountains. Children under the age of 5 years were particularly affected.

Infection with Cryptosporidium may result in severe, persistent diarrhea by disrupting the epithelial lining of the intestinal tract. It may be accompanied by cramping abdominal pain and less commonly by fever, generalized malaise, nausea, or vomiting. This disease may be life-threatening in immunosuppressed persons, especially those who are HIV-positive. Besides causing diarrhea directly, infection predisposes young children to increased diarrheal burdens and malnutrition for months afterward. This protozoan may also infect and cause diarrhea in healthy adults who are not immunocompromised, especially those living in the tropics. It poses a potential threat to people residing in temperate areas as well, including northern portions of the United States. Developing regions have a higher incidence of infection than developed regions: the infection rate in developing countries is 1.5% among the general population and 6% in individuals with diarrhea, compared to 0.2% in the healthy and 2% in those with diarrhea in developed areas. The infection rate is even higher among HIV-positive individuals with diarrhea: 24% in developing areas and 14% in developed regions. Approximately 20% of young adults in the United States show evidence of a past infection with Cryptosporidium, and more than 90% of those in some developing countries had been infected during their early childhood.

Infection with Cryptosporidium results in watery diarrhea that may last two weeks or more, even in immunocompetent hosts. Significant weight loss or dehydration may occur. In the Milwaukee outbreak, infected persons were generally ill for 4 to 12 days, with 8 to 19 bowel movements a day, and lost 4.5 kilograms (10 pounds). Low-grade fever was noted in 36% to 57% of the infected. Other persons developed an upper gastrointestinal tract infection characterized by vomiting, indicating possible infection of the stomach by this parasite. Persons experiencing vomiting appear to represent a subgroup in which disease is universally fatal. Approximately 20% to 40% of the infected persons had a recurrence of watery diarrhea after three days of normal stools. The disease was particularly severe in HIV-positive persons with low CD4+ T helper cell numbers. The elderly accounted for 36% of patients with cryptosporidiosis.

Disease in healthy persons is typically self-limiting and resolves within 30 days, while that occurring in immunocompromised individuals is most often chronic and life-threatening. Responses to infection, however, may be more complex. One or more relapses of diarrhea occurred in 45% of healthy persons who were voluntarily reinfected with the parasite, and 20% reported two to five relapses. Studies from Brazil indicate that normal children who are initially infected before the age of 1 year experience longer periods of diarrhea than those initially infected later in life and are much more likely to have multiple diarrheal episodes due to other gut pathogens. Infection of children in Africa and Peru had prolonged effects on their weight and height and also led to delayed mortality in which infected persons may not die until two years after infection. Diarrhea in children may be preceded by vomiting and anorexia. Among immunocompromised HIV-positive persons, the lower the CD4+ T helper cell number, the greater the risk of developing protracted diarrhea. Those with 150 or more CD4+ T cells per cubic millimeter of blood are usually able to clear the infection. Clinical responses in this group are nevertheless variable. While about one-third of the AIDS patients with low CD4+ cell levels have cholera-type disease requiring intravenous rehydration, 15% have only transient diarrhea, defined as more than two bowel movements per day, controllable with antimotility agents or spontaneously resolving. It is not known whether the variability in disease course is due to individual differences in host responses, to the presence of copathogens such as cytomegalovirus, or to differences in virulence of the infecting protozoan strain.

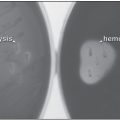

C. parvum and C. hominis are protozoa belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa, which also includes other human and animal pathogens such as Plasmodium (malaria) and Babesia (discussed in other chapters). The latter infects erythrocytes, resulting in hemolytic anemia, renal failure, severe multiorgan failure, and other serious disease manifestations. The Cryptosporidium genus is a member of the order Eucoccidiida, suborder Eimeriina, which includes other pathogens, such as Isospora, Cyclospora, and Toxoplasma. Cyclospora species are enteric pathogens similar to C. parvum, and Toxoplasma infection may lead to severe disease in infants born to infected mothers. Both of these protozoa cause serious illness in HIV-positive persons as well. Sarcocystis species are other Apicomplexans whose oocysts may easily be mistaken for Cryptosporidium. In addition to humans, Cryptosporidium species infect at least 45 vertebrate species, including fish, reptiles, birds, small mammals (rodents, dogs, cats), and large mammals (cattle, sheep, goats, and deer). The genus name means “underground” or “hidden spore.”

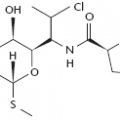

Cryptosporidia are small organisms, 3 to 6 micrometers in length, with a hardy, acid-fast, ovoid to spheroidal oocyst form. They are unable to replicate outside of the host. Sequence analysis of small subunit rRNA suggests that there is a Cryptosporidium group that infects humans and that other isolates from monkeys, calves, and sheep are closely related to each other genetically and are slightly more distantly related to C. felis from cats. C. felis, however, may also be identified by rRNA analysis in stools of AIDS patients. C. meleagridis from turkeys, C. canis from dogs, C. muris from mice, the Cryptosporidium cervine genotype from deer, and the pig genotype I are occasionally found in humans as well. The Cryptosporidium group infecting humans has a great degree of molecular heterogeneity, enabling the protozoa to be placed into two major species. C. hominis (formerly genotype 1, the H genotype) infects primarily humans and monkeys but not calves, rodents, cats, or dogs. The Milwaukee outbreak, as well as the majority of other outbreaks, involved this genotype. Only 10% of the cases of cryptosporidiosis in the United States are attributable to outbreaks. The other major species of Cryptosporidium affecting humans, C. parvum (formerly genotype 2, the C genotype), infects neonatal ruminants (calves, sheep, goats, and deer), mice, and humans. It is further divided into several families, of which family IIc is acquired from other humans and family IIa is typically a zoonotic infection.

Table 26.1 Several Apicomplexan parasites of humans

| Genus | System Affected | Prominent Symptoms |

| Cryptosporidium | Gut | Diarrhea, acute gastroenteritis |

| Sarcocystis | Gut | Diarrhea |

| Cyclospora | Gut | Prolonged diarrhea |

| Isospora | Gut | Watery diarrhea |

| Plasmodium | Blood | Hemolytic anemia, renal failure, cerebral manifestations |