Molar pregnancy and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

Donald P. Goldstein, MD Ross S. Berkowitz, MD

Ross S. Berkowitz, MD  Neil S. Horowitz, MD

Neil S. Horowitz, MD

Overview

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is among the rare human malignancies that can be cured in the presence of widespread metastases. GTN includes a spectrum of interrelated tumors, including hydatidiform mole, invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor (ETT), which has varying propensities for local invasion and metastasis. With the exception of PSTT and ETT, all GTNs arise from the cytotrophoblast and syncytial cells of the villous trophoblast and produce abundant amounts of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Measurement of hCG levels serves as a reliable tumor marker for diagnosis, monitoring of treatment response, and follow-up to detect recurrence. PSTT and ETT originate from the intermediate cells of extravillous trophoblast and produce hCG sparsely, making its use as a tumor marker that is less reliable. Although GTN most commonly follows a molar pregnancy, it may follow any gestational event, including therapeutic or spontaneous abortion and ectopic or term pregnancy. Before the development of effective chemotherapy in 1956, the majority of patients with GTN localized to the uterus were cured with hysterectomy, but metastatic disease was almost always fatal. Most women can now be cured and their reproductive function preserved if treated early and according to well-established guidelines. GTN patients are categorized using a prognostic scoring system into low- and high-risk disease based on response to single-agent chemotherapy. Low-risk GTN generally responds to monotherapy while high-risk disease requires multiagent regimens to achieve remission. Despite chemotherapy, subsequent pregnancy outcomes are similar to the general population.

Molar pregnancy and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) comprise a group of interrelated diseases that includes complete hydatidiform (CHM) and partial hydatidiform (PHM) mole, invasive mole, choriocarcinoma (CCA), placental site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor (ETT). Molar pregnancy and GTN produce a distinct tumor marker, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which can be used for diagnosis, monitoring the effects of therapy, and follow-up to detect relapse. Complete and partial moles are noninvasive, localized tumors that develop as a result of an aberrant fertilization event that leads to a proliferative process. The other trophoblastic tumors which as a group are referred to as GTN represent malignant disease because of their local invasion and metastases. GTN most commonly develops from a molar pregnancy but can rise de novo after any gestation. Although these tumors are rare, it is important for medical oncologists to understand their natural history and management because of their life-threatening potential in reproductive-age females and their high degree of curability with preservation of reproductive function if treated early and appropriately.1, 2 Despite the advances made in the management of GTN over the past 60 years, patients with protracted delays in diagnosis, particularly after nonmolar pregnancies, still present with extensive tumor burdens and are at substantial risk for treatment failure and death.

Incidence

The reported incidence of molar pregnancy and GTN varies substantially in different regions of the world.3 The incidence of complete and partial molar pregnancy in North America and Europe is approximately 1 : 1250 and 1 : 650, respectively, whereas the incidence in Asian countries is 3–10 times greater.4, 5 Variations in the incidence rates of molar pregnancy throughout the world may result from differences between reporting hospital-based versus population-based data.

The incidence of GTN is also difficult to establish with certainty because accurate epidemiologic data is not available in most countries. Approximately 50% of GTN cases arise from molar pregnancy, 25% from miscarriages or tubal pregnancies, and 25% from term or preterm pregnancy.6 GTN which develops after a non-molar pregnancy is usually due to CCA, whereas PSTT and ETT occur rarely. The incidence of GTN following a non-molar pregnancy in Europe and North America is estimated at 2–7 per 100,000 pregnancies, whereas in Southeast Asia and Japan, the incidence is higher at 50–200 per 100,000 pregnancies, respectively.7, 8

Risk factors

The two main risk factors for molar pregnancy and GTN are extremes of maternal age (especially over 35 and under 16) and a history of previous mole.9–13 Parazzini et al.11 noted that the risk for CHM was increased twofold for women older than age 35 years and 7.5-fold for women older than age 40 years. Ova from older women may be more susceptible to abnormal fertilizations. Most cases of molar disease and GTN occur in women under 35 because of the greater number of pregnancies in this age group. The risk for PHM has not been associated with maternal age.

Histopathologic classification of GTN

Hydatidiform mole may be categorized as either complete or partial based on gross morphology, histopathology, and karyotype.14, 15 CHM is characterized by hydropic villi with trophoblastic hyperplasia. Embryonic or fetal tissues are not identifiable. Partial moles are characterized by the presence of two populations of chorionic villi, some appearing normal and some exhibiting focal swelling and focal trophoblastic hyperplasia. Fetal and embryonic tissues are commonly present. Locally invasive or metastatic GTN that develops after either a complete or partial mole can have the histologic features of either molar tissue or CCA.

CCA does not contain chorionic villi but is composed of sheets of both anaplastic cyto- and syncytiotrophoblasts. Although CCA is most commonly preceded by a CHM, it may develop after any gestation. After a non-molar pregnancy, persistent GTN usually has the histologic pattern of CCA but rarely can be present as PSTT or ETT. CCA is a highly vascular tumor that disseminates via the blood stream initially to the lungs. Distant sites such as the brain, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and spleen are usually late manifestations of the disease in patients where there has been delayed diagnosis.

PSTT and ETT are uncommon variants of CCA, which are composed almost entirely of mononuclear intermediate trophoblast and do not contain chorionic villi.16, 17 Both PSTT and ETT tend to infiltrate the myometrium and, in contrast to CCA, metastases are a late manifestation of the disease. These tumors display a wide clinical spectrum and when metastatic can be difficult to control even with surgery and chemotherapy. They are characterized by low hCG levels so a large tumor burden may be present before the disease is diagnosed.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Post-molar GTN

Complete moles develop uterine invasion or metastasis in about 15% and 4% of patients, respectively.18 Approximately 1–4% of patients with PHM develop persistent tumor, which is generally non-metastatic.19 After molar evacuation, all patients must be monitored for the development of post-molar GTN, defined as those patients who develop persistently elevated hCG levels, require chemotherapy and/or excisional surgery, or have evidence of metastases. According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria, the presence of post-molar GTN should be diagnosed if the following is present: (1) serum hCG values that plateau (decline of <10% for at least four values over 3 weeks); (2) serum hCG levels rise (increase more than 10% over 2 consecutive weeks); and (3) persistence of detectable serum hCG for more than 6 months after molar evacuation.20

Patients on rare occasion present with a false positive elevation in their serum hCG concentration owing to a number of factors other than GTN. The differential diagnosis of an elevated hCG value includes (1) pregnancy, (2) germ cell tumor of the ovary or other site, (3) non-trophoblastic gonadotropin-producing tumor (e.g., hepatoma), or (4) phantom hCG caused by heterophilic antibody.21 Post-menopausal women have also been reported to have detectable low hCG levels of pituitary origin, which can be suppressed by hormone replacement therapy.22

Non-metastatic GTN

Locally invasive GTN also occurs infrequently after non-molar pregnancies.18 These patients may present with persistently elevated hCG levels, irregular vaginal bleeding, uterine subinvolution, or asymmetric uterine enlargement. Theca lutein ovarian cysts are rare in the absence of high levels of hCG (>100,000 mIU/mL). The trophoblastic tumor may erode into uterine vessels, causing vaginal hemorrhage, or may perforate through the myometrium, producing intra-abdominal bleeding. Bulky necrotic tumors in the endometrial cavity may also serve as a nidus for sepsis, causing pelvic pain and purulent discharge.

Metastatic GTN

Metastases develop in approximately 4% of patients after complete mole and infrequently after other gestations.18 When metastases occur, the pathology is usually CCA because this tumor has a propensity for early vascular invasion and dissemination. The presenting signs and symptoms in these patients depend on the sites of metastasis: hemoptysis from lung lesions, acute neurologic deficits from intracranial hemorrhage, and so on.

The most common site of metastasis is the lung. Eighty percent of patients with metastatic GTN have pulmonary involvement on chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT). Because respiratory symptoms and radiographic findings may be striking, the patient may be thought to have a primary pulmonary process. Pulmonary hypertension can develop as a result of pulmonary arterial occlusion by trophoblastic emboli. The development of early respiratory failure requiring intubation is associated with a dismal outcome.23 Gynecologic symptoms may be minimal or absent even when the patient has extensive metastases. The diagnosis of GTN should be considered in any woman in the reproductive age group with unexplained pulmonary or systemic symptoms.

Vaginal metastases are present in 30% of patients with metastatic GTN. Because these lesions are highly vascular, they may hemorrhage if biopsied.18

Hepatic and cerebral metastases occur in approximately 10% of patients with metastatic GTN. Hepatic and cerebral lesions invariably have the histologic pattern of CCA and usually follow a non-molar pregnancy. These patients characteristically have protracted delays in diagnosis and extensive tumor burdens. Virtually, all patients with hepatic and cerebral metastases have concurrent pulmonary or vaginal involvement.24, 25

Staging and risk assessment

An anatomic staging system for GTN was adopted by the FIGO in 198220:

- Stage I: Lesion confined to uterus.

- Stage II: Lesion outside uterus but confined to vagina and pelvis.

- Stage III: Lung metastases with or without evidence of uterine or pelvic disease.

- Stage IV: Distant metastatic sites such as the brain, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and spleen.

In addition to anatomic staging, the World Health Organization (WHO) has adopted a prognostic scoring system (Table 1) that reliably predicts the risk of drug resistance and assists in selecting the appropriate chemotherapy.20, 27 Prognostic scores <7 are associated with a low risk of resistance to single agent chemotherapy. When the prognostic score is 7 or greater, the patient is considered to be at high risk of developing drug resistance to single agent therapy and requires intensive combination chemotherapy. Patients with stage I GTN usually have a low-risk score and those with stage IV disease generally have a high-risk score. Therefore, the distinction between low and high risk mainly applies to patients with stages II and III disease. The FIGO stage is designated by a Roman numeral and is followed by the modified WHO prognostic score designated by an Arabic number separated by a colon (e.g., II:6).

Table 1 Scoring system for gestational trophoblastic tumors based on prognostic factors

| Scoreb | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Age (years) | <39 | >39 | — | — |

| Antecedent pregnancy | Mole | Abortion | Term | — |

| Intervala | <4 | 4–6 | 7–12 | — |

| hCG (IU/L) | <103 | 103–104 | 104–105 | — |

| ABO groups (female × male) | — | O × A | B | — |

| A × O | AB | — | ||

| Largest tumor, including uterine tumor | — | 3–5 cm | 5 cm | — |

| Site of metastases | — | Spleen, kidney | Gastrointestinal tract and liver | Brain |

| Number of metastases identified | — | 1–4 | 4–8 | >8 |

| Prior chemotherapy | — | — | Single drug | Two or more drug |

a Interval is the time (months) between end of antecedent pregnancy and start of chemotherapy.

b The total score for a patient is obtained by adding the individual scores for each prognostic factor. Total score: <7 = low risk; and ≥7 = high risk.

Source: Data from Matsui et al. 2004.26

Data from Charing Cross Hospital indicate that only 30% of low-risk patients with a WHO prognostic score of 5–6 can be cured with monotherapy, which suggests that a multidrug regimen should be administered initially. These patients characteristically present with pre-treatment hCG levels >100,000 mIU/mL and ultrasound evidence of a large tumor burden.28

Management of GTN

Pretreatment evaluation and staging of GTN

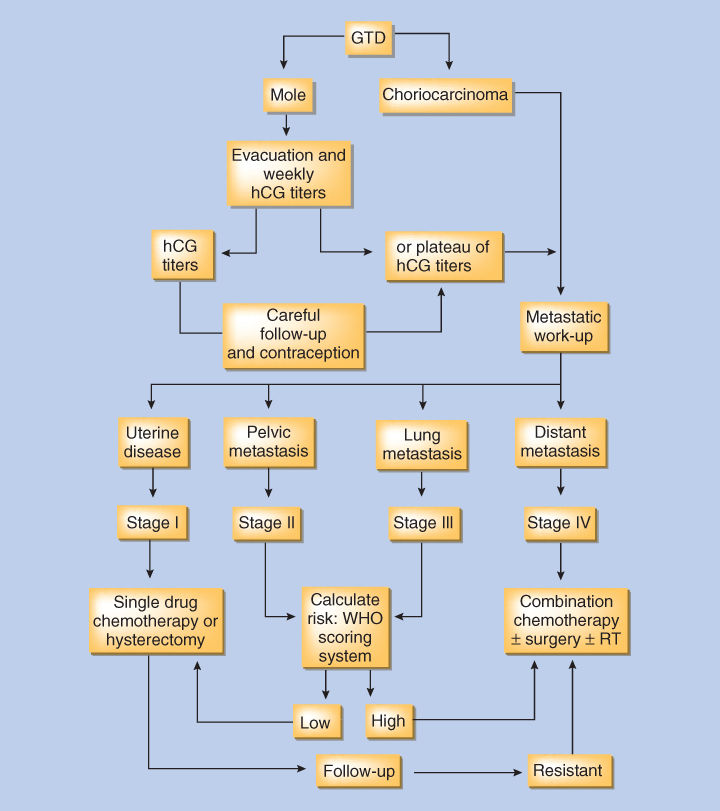

Patients with GTN must undergo a thorough evaluation in order to determine their stage and risk status, which will guide the clinician in selecting the appropriate treatment (Figure 1). The physical examination should always include a vaginal speculum examination to detect implants, which can hemorrhage. Radiographic evaluation should include a pelvic ultrasound to look for evidence of retained trophoblastic tissue in the uterine cavity, myometrial invasion, and to evaluate the pelvis for local spread. Chest imaging is also required, as the lungs are the most common site of metastases. Although chest CT scans are more sensitive than a chest X-ray, they are not included in staging as detection of occult pulmonary metastases does not affect outcome. Pulmonary metastases can be detected by chest CT in up to 40% of patients with a negative chest X-ray.29 In the absence of pulmonary and vaginal metastases, involvement of distant organs such as the brain and liver is rare. As long as the clinical picture is compatible with GTN, metastases need not be biopsied because of their vascularity and the risk of hemorrhage.

Figure 1 Algorithm for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD).

Management of low-risk GTN

Primary therapy of low-risk GTN

Low-risk GTN includes patients with both stage I (non-metastatic) and stages II and III (metastatic) GTN whose prognostic score is <7. In patients with stage I GTN, the selection of primary therapy is based on the patient’s desire to preserve fertility. If the patient has completed her childbearing, hysterectomy should be considered.30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree