Modified radical mastectomy (MRM) involves complete removal of the breast along with the overlying skin and all axillary contents. It has been, and continues to be, a critical component of breast cancer surgery. Although partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy is an accepted form of therapy, recent studies indicate that the rates of mastectomy in the United States are actually rising.1 It is therefore critical for the practicing surgeon to be familiar with the surgical techniques available for performing mastectomy and reducing postoperative complications.

For performance of MRM, patients are placed in a supine position with the ipsilateral arm extended. The patient is shifted to a position as close to the edge of the operating table as safe to facilitate access and visualization. A small roll, typically either a rolled-up operative towel or sheet, can be placed longitudinally just posterior, and medial to, the latissimus muscle. In heavy patients, this can assist in palpating and dissecting the medial aspect of the latissimus muscle. Additional blankets should be placed under the extended arm to ensure the shoulder is at a level, neutral position rather than falling posteriorly. The arm should be prepped circumferentially and draped into the field with either a surgical stockinette or towels, which can be wrapped around the arm. A 6- to 8-cm length of the upper arm and the axillary area remains exposed. This ensures mobility of the arm if needed for access to the axilla and minimizes exposed skin. The surgeon should stand inferior to the extended arm. The assistant can stand either superior to the arm or on the contralateral side.

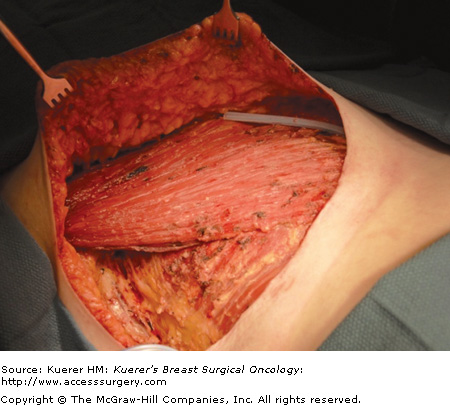

The incision for an MRM should be oriented in a fashion to remove skin overlying the tumor, and, if reconstruction is not planned, a large enough skin ellipse should be removed to allow for a flat chest wall at closure. The avoidance of skin flap redundancy reduces seroma formation and skin edge necrosis. Longer skin flaps will have more complications related to inadequate blood supply. Generally, an elliptical incision incorporating the nipple areolar complex is appropriate (Fig. 64-1). If a prior needle or surgical biopsy has been performed, the biopsy site should be encompassed within the skin ellipse. The incision should include 1.0- to 2.0-cm margins away from the tumor or the previous biopsy incision. For a very superficial tumor, it is prudent to take a wider skin margin to avoid a positive anterior soft tissue margin. The flaps are elevated superiorly to the clavicle and lateral deltopectoral groove, medially to the sternal border, laterally to the latissimus dorsi muscle, and inferiorly to the upper edge of the rectus sheath (Fig. 64-2). The breast in an MRM should be removed en bloc with the axillary contents. The incision should extend far enough laterally to allow adequate exposure for axillary dissection. For details on axillary lymph node dissection, see Chapter 63.

The use of electrocautery for elevation of the mastectomy skin flaps results in less blood loss than scalpel dissection. In the era of scalpel dissection, blood transfusion during mastectomy was common. Comparative studies of scalpel versus electrocautery dissection reveal a statistically significant reduction in blood loss with electrocautery.1-4 With electrocautery dissection, transfusion is infrequent.

The mastectomy incision is made with the knife through the skin and dermis to allow the skin edges to separate. The skin edges are then grasped with skin hooks or Lahey clamps to provide traction during the flap elevation. The cautery is set on the lowest level that allows transection of the tissues with the least fat necrosis. With the coagulation setting, there is better control of bleeding; the cutting mode vaporizes cells and is less effective with coagulation. The goals in flap elevation are to leave some subcutaneous fat on the skin flap and to avoid leaving breast tissue. The subcutaneous fat is incised just anterior to the superficial fascia. A thinner patient generally has thinner flaps than a heavier patient who has more subcutaneous fat. In the thin patient, there may be only 2 to 3 mm of fat on the skin flap. It is critical to preserve the subcutaneous vascular plexus. Recent anatomic studies indicate significant interdigitation of fat with the breast parenchymal tissue. It is therefore important to remain in the plane of the subcutaneous fat and avoid deeper dissection into the fat interdigitating with the glandular tissue.5 This error is more likely to occur in the patient with thicker subcutaneous fat or a fatty replaced breast. With upward retraction on the skin edges, the tip of the cautery is used to incise the fat along the full length of the skin incision, maintaining a broad front of dissection. The dissection is performed under direct vision so that the thickness of the flap and the nature of the tissue transected can be visualized. The cautery is applied in a smooth sweeping fashion medial to lateral and lateral to medial. The opposite hand is used to retract the breast in the direction opposite the skin flap. During the dissection of the flap, it is important to advance the retracting hand to apply traction close to the point of the tissue transection with the cautery. Inadequate retraction results in uneven flaps and more difficulty incising the tissue. As the extent of dissection proceeds farther from the skin edge, it is usually necessary to replace the skin hooks with long lighted retractors. The shorter Bovie electrocautery tip can be replaced with a longer tip to facilitate the dissection at the extreme edges of the flap elevation. As with all techniques of flap dissection, it is important to avoid excessive skin traction that may compromise blood supply to the flap. With this technique, it is important not to get too close to the skin with the cautery, which can result in thermal injury. This is most likely to occur while using the cautery to coagulate small vessels. The visualization of the white dermal tissue during flap elevation should prompt the surgeon to re-establish the plane of dissection in the subcutaneous tissue. The skin edges are covered with moist laparotomy pads to protect the skin edges during retraction for removal of the breast from the pectoral muscle. During the subsequent breast removal, the surgeon and assistants must be mindful of the skin flaps and apply retraction as gently as possible.

Tumescent mastectomy has been described under local anesthesia6 with the use of specialty tumescent infiltration trocars7 or with scissors.8 The scissors technique uses equipment readily available in the operating room and we therefore prefer it. The use of sharp dissection rather than electrocautery minimizes collateral damage and may reduce mastectomy skin flap necrosis rates, a complication present in up to 30% of patients.9Figure 64-3 shows the specialty equipment necessary for the performance of total mastectomy with the tumescent technique. Extremely sharp scissors are needed, such as Jarit Supercuts (Jarit; Hawthorne, New York), which are typically used for surgical facelifts. Scissors with a slight degree of curvature assist in following the contour of the breast and staying in the appropriate plane. Freeman facelift retractors (Anthony Products Inc.; Indianapolis, Indiana) are used to retract the skin. Double skin hooks may also be used for retraction. Additionally, a 60-mL syringe and a 22-G spinal needle are used for infiltration of the tumescent solution. Tumescent solution should include normal saline, lidocaine, and epinephrine. A combination of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine (20 mL) is readily available in the operating room and may be mixed with 60 mL of injectable normal saline. Alternatively, using 1 amp (1:100,000) of epinephrine with 20 mL of lidocaine and 1 L of injectable normal saline provides increased volume and may provide better hemostasis.

After the incision is made, a small lip of tissue is raised just below the dermal layer across the entire incision (Fig. 64-4). To minimize collateral damage, electrocautery is typically set on cutting current. Tension with the contralateral hand is key in visualizing the appropriate plane.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree