Metastatic Disease

Timothy A. Damron

Metastatic disease to bone accounts for the largest number of bone lesions in patients greater than 40 years of age. In fact, the differential diagnosis for an aggressive bone lesion in an adult is “mets, mets, mets, myeloma, lymphoma, and sarcoma,” in decreasing order of frequency. Even solitary bone lesions in this age group are most commonly due to metastatic carcinoma. The role of the orthopaedist is to establish or confirm the diagnosis, evaluate for risk of fracture, and stabilize or otherwise surgically treat pathological fractures and impending fractures. Pathologic fractures are discussed in Chapter 4, Treatment Principles.

Despite the prevalence of metastatic carcinoma as a cause of bone lesions in this age group, bone lesions should never be assumed to be due to metastatic disease without compelling evidence. One of the most important pitfalls in the evaluation and treatment of bone lesions in adults is the erroneous treatment of a sarcoma under the mistaken assumption that the lesion is due to metastatic carcinoma. Because the principles for treatment differ so greatly between sarcomas and metastatic carcinomas, the specific diagnosis must be established before initiation of care. Hence, an aggressive bone lesion in an adult, while frequently due to metastatic disease, should be considered a sarcoma until proven otherwise.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

Common sources of bone carcinomas metastasizing to bone in adults

Most common “osteophilic” carcinomas

Breast, prostate, lung, kidney, thyroid (the “big 5”)

Melanoma: emerging osteophilic tumor

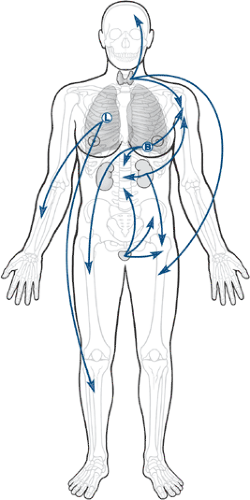

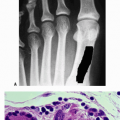

Common sources of metastatic carcinoma (Fig. 8-1)

Most common when there is an established history of cancer:

Breast and prostate

Most common when there is no established history of cancer

Lung and kidney, respectively

Common sources of metastases to bone in pediatric patients

Neuroblastoma (<5 years old) > rhabdomyosarcoma > retinoblastoma

Common sources for unusual patterns of distribution (any primary may)

Most common metastases distal to the elbows and knees (“acral” mets)

Lung and kidney, respectively

50% of acral mets due to lung carcinomas

Most common metastases to soft tissue

Lung and kidney, respectively

Epidemiology

Frequency of common sources of bone carcinoma metastases (Table 8-1)

New cases: prostate > breast > lung > kidney > thyroid

Frequency of metastases and survival according to primary source (Table 8-2)

Table 8-1 Epidemiology of The “Big Five” Most Common Primary Sources of Metastases to Bone | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pathophysiology

While the local “soil” in which the metastases deposit is very important to allowing the establishment of a tumor growth, the distribution of metastases is intimately related to the route that metastases take from their site of origin to get to their ultimate destination (Fig. 8-2 and Table 8-3). Most metastases escape the circulation by traversing thin-walled venous structures, so they follow the distribution of the systemic (caval), portal, or vertebral venous circulation (Batson’s plexus; Box 8-1) to arrive within the lung, liver, or bone, respectively (see Table 8-3). The axial pattern of distribution of the vertebral venous circulation is reflected in the predominance of axial locations for the most common sites of bone metastases (see Fig. 8-2). Lung carcinomas, given their location, have a relatively greater frequency of accessing the arterial circulation by means of eroding the pulmonary venous vasculature within the lungs. Hence, lung carcinomas are the most common source of bone metastases to the acral skeleton (distal to the elbow and knee).

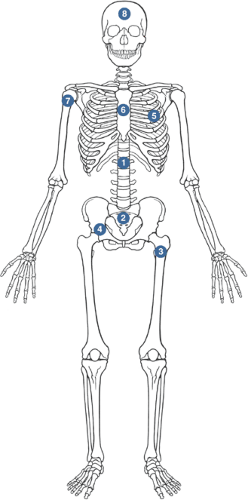

Distribution of Metastases Overall

Common sites

Thoracolumbar spine > sacrum > proximal femur > pelvis > ribs > sternum > proximal humerus > skull

“Soil and seed” versus circulation controversy

Classic argument: idea that certain tissues are better “soil” for cancer cells versus idea that the circulation determines the patterns of metastases

“Soil hypothesis” from Paget (1889) with modern considerations

Metastatic tumors have a predilection for red marrow (proximal sites) over yellow marrow.

Adhesion molecules favor recruitment of tumor cells.

For example, stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) recruits prostate cancer cells via interaction with chemokine receptor (CXCR4) on tumor cells.

Table 8-2 Fraction of Patients with Each Primary Source Who Will Develop Metastases, Fraction of Those That Will Involve Bone, and Survival With Metastases

Primary Tumor

Pts. with Metastatic Disease (%)

Pts. with Metastases who Have Bone Involvement Clinically (%)

Median Survival After Diagnosis of Metastases (mo)

Mean 5-year Survival Rate (%)

Breast carcinoma

65–75

24

20

Prostate carcinoma

65–75

30–40

40

25

Lung carcinoma

30–40

20–40

<6

<5

Renal carcinoma

20–25

15–25

6

10

Thyroid carcinoma

60

20–40

48

40

Multiple myeloma

95–100

100

20

10

Data from Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 1997;80:1588–1594.

Table 8-3 Circulation Theory of Metastatic Distribution

Circulatory Component

Consequent Site of Metastases

Systemic (caval) venous circulation

Lung

Portal venous circulation

Liver

Batson’s vertebral venous plexus

Bone

Pulmonary venous circulation

All organs, bones

Growth factors capable of stimulating tumor proliferation are replete in bone.

Insulin-derived growth factor (IGF)

Bone morphogenic proteins (BMP)

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)

“Circulation theory” from Ewing (1928) (see Table 8-3)

Box 8-1 Features of Batson’s Plexus

Network of interconnected veins with thin, low-pressure walls

Extends longitudinally from skull to sacrum, supplying segmental vertebra

Location outside thoracoabdominal cavity: unaffected by Valsalva maneuvers

Retrograde movement possible via valveless veins

Connections to common osteophilic primaries (breast, prostate, lung, kidney, thyroid)

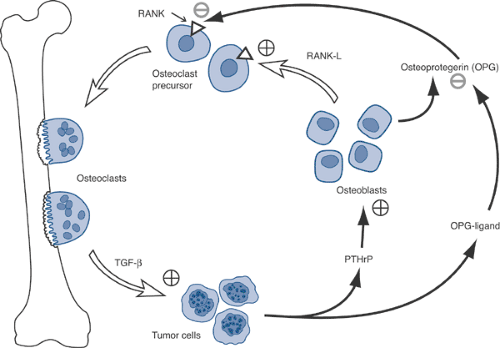

Source of Destruction: Role of the Osteoclast

Osteoclasts, not tumor cells, destroy bone.

Osteoclasts mediate tumor cell attachment to bone.

Breast cancer cells recruit osteoclasts via parathyroid hormone–related protein (PTHrP) (Fig. 8-3).

Tumor cells produce PTHrP and osteoprotegerin ligand (OPG-L).

PTHrP stimulates osteoblasts to release osteoprotegerin (OPG) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa ligand (RANK-L).

RANK-L stimulates the RANK receptor on osteoclast precursors to cause differentiation into osteoclasts, which leads to resorption.

Osteoprotegerin inhibits the interaction of RANK-L with RANK, decreasing the bone resorption.

Myeloma cells stimulated by interleukin-6 (IL-6) released by osteoclasts

Classification

Metastatic disease to bone represents the most advanced stage of any primary malignancy and carries a similar weight in staging systems for these cancers as metastases to other distant sites. While the TLM (tumor, lymph node, metastasis) classification systems differ in their details between sarcomas and the common carcinomas that metastasize to bone, spread to bone in all cases shifts the disease to the highest level.

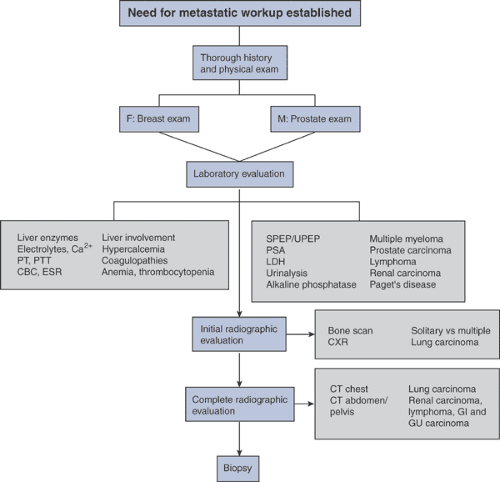

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of metastatic disease to bone relies on assimilation of data from numerous sources (Algorithms 8-1 and 8-2). In some cases, the diagnosis is apparent on review of only the history, physical examination, and radiographs.

However, in many cases in which the orthopaedic surgeon will be involved, the diagnosis will require a more comprehensive evaluation and biopsy for confirmation.

However, in many cases in which the orthopaedic surgeon will be involved, the diagnosis will require a more comprehensive evaluation and biopsy for confirmation.

Physical Examination

Key examinations search for common sources of bone metastases:

Breast, prostate, lungs, flank (kidney), thyroid

Comprehensive evaluation for other less common sources of bone metastases and sites of concurrent metastases (Table 8-4):

Skin (melanoma), lymphatics (lymphoma), guaiac examination (colon)

History

Pain

The most common presenting clinical symptom of bone metastases

Night pain characteristic

Less common presentations of metastases

Soft tissue mass (from soft tissue extension or soft tissue metastasis)

Incidental findings on staging studies coincident with primary tumor diagnosis

Paraplegia (spine metastases with or without pathologic spinal fracture)

Pathological fracture (usually preceded by pain, even of short duration)

Soft tissue metastases: more frequently painful rather than painless, whereas most soft tissue sarcomas are painless

Table 8-4 Comprehensive Systemic Approach for Physical Examination and Review of Systems Relative to Patients with Potential Metastatic Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree