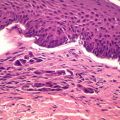

Figure 17.1

H&E 25×. Low magnification shows tumor filling the upper dermis

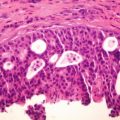

Figure 17.2

H&E, 400× magnification. Chords and tumor nests are visible. Some nests show duct formation where tumor cells are lined along the edge with a central fluid-filled space

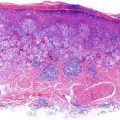

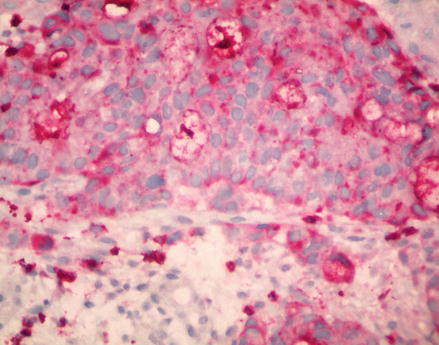

Figure 17.3

CEA 400×. Positive staining of the tumor cells portend an adenomatous origin

Discussion

The overall incidence of cutaneous metastasis from any type of visceral malignancy is 5.4 % [1]. However, breast cancer is the most frequently encountered cutaneous metastasis carcinoma and has an even higher rate of cutaneous presentation. One study showed that of 7518 patients with visceral malignancies, approximately 26.5 % of females with breast cancer were found to have cutaneous metastasis [2]. On average, these cutaneous signs appear 5 years after the initial diagnosis and treatment for the breast cancer [3].

Most clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer are acute in onset and nodular in appearance. A retrospective review conducted by Mordenti et al. determined that 80 % presented as skin papules or nodules, 11 % as telangiectatic carcinomas, 3 % as erysipeloid carcinomas, another 3 % as “en cuirasse”, 2 % as alopecia neoplastica, and 0.8 % presented in a zosteriform fashion [4]. Unique to metastatic cutaneous breast carcinomas are the erysipeloid and “en cuirasse” presentations. The erysipeloid carcinomas present as an expanding, erythematous patch or plaque. The “en cuirasse” version presents as a hard, leathery, morphea-like indurated plaque that covers the chest, much like the armor breastplate from which its name is derived [3].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree