Extrahepatic Disease

One special circumstance of liberalizing indications for hepatic metastasectomy that deserves mention is that of extrahepatic metastases. The presence of additional foci of metastatic disease outside of the liver (e.g., pulmonary, peritoneal, retroperitoneal) was once universally considered to be an absolute contraindication to hepatic resection. However, there is now accumulating experience with combined hepatic and extrahepatic metastasectomy. Although this experience is derived from highly unique and selected cases, in the context of this careful patient selection, it is apparent that patients undergoing resection of hepatic and pulmonary metastases can experience a median overall survival of 3 to 4 years (recurrence-free survival of approximately 2 years), and patients undergoing resection of hepatic and peritoneal metastases can experience a median overall survival of 2 to 3 years (recurrence-free survival of approximately 2 years). Interestingly, comparatively worse survival outcomes have been described for patients presenting with hepatic pedicle or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases.40,41

Thermal Ablation

Thermal ablation using MWA or RFA has the advantage of allowing greater parenchymal sparing than hepatic resection, particularly for deep-seated, centrally located tumors. As such, ablation is often used instead of or in conjunction with resection. Ablation can be performed intraoperatively during open or laparoscopic procedures, or percutaneously in a nonoperative setting. The less invasive nature of ablation can be attractive for patients who are suboptimal candidates for major operative intervention. Ablation is particularly appealing for cases of colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases that have recurred following previous resection, as it avoids the heightened risks of repeat hepatic resection. A review of single and multi-institutional experiences with thermal ablation for hepatic colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases indicates a risk of local recurrence (i.e., incomplete ablation; Table 125.2).42–47 In experienced hands, the risk of local recurrence can be <10%. The biggest risk factor for local recurrence is tumor size; for small tumors (<1 to 2 cm), the likelihood of incomplete ablation with modern MWA and RFA is quite small. The overall survival estimates observed in these series is significantly lower than those associated with hepatic resection; however, this is likely reflective of the significant selection bias that is inherent in any decision to undertake ablation over operative resection.

Adjuvant and Perioperative Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to decrease the risk of recurrence and improve survival for patients with stage III colorectal adenocarcinoma; moreover, systemic chemotherapy clearly prolongs survival for patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. For these reasons, operative resection and systemic chemotherapy are typically used in close conjunction with one another, even for patients with readily resectable hepatic metastases. A fair amount of effort has been expended in an effort to measure the benefit of this multimodal approach to patients with resectable hepatic colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases. The largest multicenter prospective randomized trials evaluating the influence of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy are summarized in Table 125.3.48–52 Two prospective randomized clinical trials comparing surgical resection alone to surgical resection followed by postoperative 5-FU and leucovorin identified a suggestion of improvement in progression-free survival among patients randomized to receive chemotherapy, but no improvement was seen in overall survival.48,49 Although some have argued that the combination of 5-FU and leucovorin is largely of historical interest because of the advent of more effective regimens of chemotherapy, a randomized trial comparing adjuvant 5-FU/leucovorin to FOLFIRI showed no differences in survival.50 Indeed, the more recent European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 40983 randomized trial comparing patients treated with surgical resection alone versus surgical resection with perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy also only suggested an improvement in progression-free survival on subset analysis.51,52 It is worth recognizing that patients who eventually develop recurrent metastatic disease after resection are likely to receive systemic chemotherapy, regardless of the nature of perioperative or postoperative treatment. Thus, it is quite possible that the reason these trials did not show differences in overall survival was because systemic chemotherapy was able to “salvage” patients who developed disease recurrence.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Regardless of these uncertainties, most patients with hepatic colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases are treated in a multimodal manner. Indeed, for patients with radiographic evidence of resectable disease (and whose underlying medical condition permits operative therapy), the decision is generally not whether to give chemotherapy, but when. It is likely that optimal therapy of hepatic colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases involves the multimodal use of systemic chemotherapy and operative tumor resection (or ablation). However, controversy persists regarding the ideal sequencing of treatment for patients with resectable tumors. The routine use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (administered prior to operative therapy) offers several theoretical advantages: (1) it allows one to measure the chemosensitivity of tumors by observing radiographic evidence of tumoral regression; (2) in circumstances of rapid disease progression, as is the case with synchronous metastases, it allows for a period of safe observation in which other occult foci of metastases may become evident; and (3) it helps to ensure that patients will receive a vital component of multimodality therapy (chemotherapy), even if they develop major postoperative complications that prevent them from completing additional therapy. As the response rate of hepatic colorectal metastases to contemporary chemotherapy has improved to well over 50%, the rationale for using neoadjuvant therapy for drug selection or as a means of monitoring for prognostically adverse disease progression has diminished.53–55

Conversion to Resectability

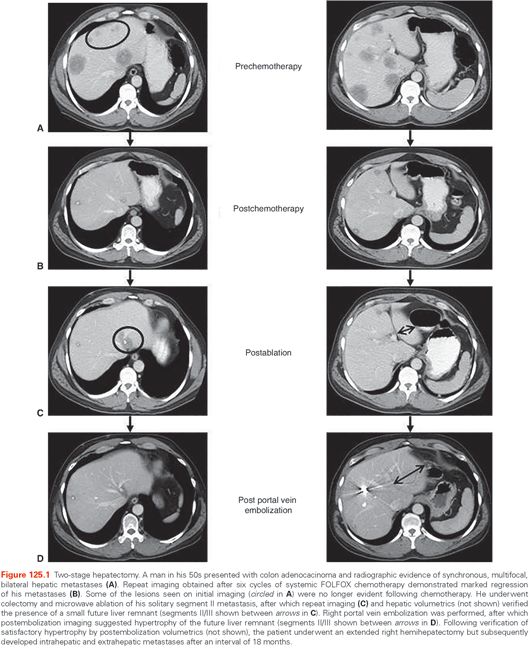

A major advancement in the treatment of metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma has been in the array of technologies that can occasionally enable patients with initially unresectable disease to eventually undergo complete tumor extirpation. In circumstances where the FLR is insufficient in size, PVE and two-stage hepatectomy are commonly employed. A typical case example is illustrated in Figure 125.1.

On occasion, the extent of tumor burden is so great that PVE and two-stage approaches are not enough to achieve resectability. Fortunately, the steady improvements in response rates to chemotherapy have led to the use of systemic chemotherapy as a means of converting some patients with unresectable disease to resectability.56 In one illustrative experience of 1,104 patients with unresectable hepatic colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases treated over an 11-year period at the Hôpital Paul Brousse, 138 patients (12.5%) demonstrated sufficient disease regression after an average of 10 cycles of chemotherapy to permit an attempt at resection; potentially curative hepatic metastasectomy was possible in 93% of the 138 patients, resulting in actuarial 5-year survival estimates of 33%.57 It is important to recognize that this aggressive utilization of surgical resection for patients with advanced disease is unlikely to be curative; over the course of follow-up in this series, 80% of patients eventually developed disease recurrence, and overall survival in this select cohort of patients was significantly poorer than in patients who initially presented with resectable disease. However, it is likely that the outcomes observed following such aggressive surgical interventions might not have occurred following chemotherapy alone. A recent analysis from the MD Andersen Cancer Center compared patients with extensive tumor burden who exhibited a radiographic response to systemic chemotherapy. After controlling for a number of relevant patient and tumor characteristics, they observed a striking difference in survival between patients who underwent hepatic metastasectomy at some point in their treatment versus patients who did not.58 Although this study cannot account for all of the selection biases inherent in a retrospective comparison of surgical and nonsurgical patients, the magnitude of difference suggests that operative metastasectomy may likely impart an independent influence on survival duration.

Biological Agents

The armamentarium of systemic treatment options has been greatly expanded by the introduction of so-called biologic agents, which are targeted inhibitors or antibodies that interfere with the function of specific proteins and receptors involved in carcinogenic signaling pathways. Biologic agents such as bevacizumab, which targets the angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor,59–61 and cetuximab, which targets the mitogenic epithelial growth factor,62,63 have been shown to improve response rates and progression-free survival when used in conjunction with traditional chemotherapy. One concern related to the use of bevacizumab is its potential negative influence on wound healing and bleeding. Although the extent to which preoperative administration of bevacizumab affects perioperative complication rates remains uncertain, a preferred approach has been to delay operative intervention until 4 to 8 weeks after the last administration of bevacizumab; when used in this manner, no significant changes in wound-related complications have been observed.64,65 An important variable to consider when using cetuximab is the tumoral mutational status of the KRAS oncogene; retrospective and prospective analyses have verified that the benefit associated with the use of cetuximab is confined to the KRAS wild-type population.66,67

Chemotherapy-Associated Hepatotoxicity

An important argument against neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the risk of chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity. As the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents against colorectal adenocarcinoma has increased, so too has their side effect profile of hepatotoxicity.68–70 Agents like 5-FU and irinotecan have been associated with a risk of hepatic steatosis, which can evolve into steatohepatitis. Livers afflicted by steatosis appear rounded and pink, and those with steatohepatitis demonstrate fibrotic changes that, over time, can progress to frank cirrhosis; both are associated with higher risks of intraoperative hemorrhage and impaired hepatic regeneration. Oxaliplatin is primarily toxic to endothelial or vascular tissues in the liver, and has been associated with sinusoidal vasodilation and obstruction that appears as a patchy bluish discoloration of the liver; heavy oxaliplatin use has been associated with higher risks of intraoperative hemorrhage. Several retrospective studies have reported higher rates of perioperative morbidity and prolonged hospitalizations in patients undergoing hepatic metastasectomy after prolonged courses of chemotherapy,71,72 and the aforementioned European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 40983 prospective trial identified a significantly higher rate of postoperative complications in the perioperative chemotherapy arm versus the operation alone arm (25% versus 16%, p = 0.04).51 As outlined previously, the ability of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy to improve overall survival for patients undergoing hepatic metastasectomy remains unclear; whether and how the timing of chemotherapy vis-à-vis resection affects survival is unknown. Because prolonged administration of chemotherapy can induce enough liver damage to challenge the safety of surgical intervention, some clinicians have argued against the routine administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with resectable hepatic metastases. At the very least, care should be taken to limit the duration of preoperative chemotherapy so as to minimize the risk of chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity; based on retrospective analyses, it appears that the risk of perioperative complications increases after six or more cycles of preoperative chemotherapy. Identification of chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity can be challenging, as routine laboratory assessment of hepatic function is typically not sensitive enough to identify these changes. Thrombocytopenia can be suggestive of hypersplenism resulting from hepatic fibrosis–induced portal hypertension. Radiographic evidence of steatosis (as estimated by a decrease in hepatic parenchymal attenuation on CT imaging or signal dropout on in- and out-of-phase MRI sequences) or fibrosis (as indicated by alterations in hepatic segmental atrophy or hypertrophy or irregularities in parencymal contour) can also be suggestive of hepatotoxicity.73 Because of the inconsistency with which these preoperative diagnostics identify significant hepatotoxicity, some have argued for the routine use of percutaneous liver biopsy (to evaluate for steatosis, fibrosis, or sinusoidal obstruction) in patients who have received intensive systemic chemotherapy.74

Hepatic Artery Infusional Chemotherapy

As stated previously, hepatic metastases preferentially derive their perfusion from the hepatic arterial circulation. Floxuridine (FUDR) is a derivative of 5-FU that is rapidly metabolized by the liver. HAI of FUDR has therefore been developed as a means of delivering extremely high doses of chemotherapy to hepatic tumors with negligible systemic exposure. Clinical trials have demonstrated impressive benefits with the use of adjuvant and neoadjuvant HAI chemotherapy.75–77 However, many of these trials were undertaken prior to the availability of more modern chemotherapeutic agents; as a result, the contemporary role and benefit of HAI chemotherapy is not clear. Use of HAI FUDR has been associated with favorable response rates when used in patients who have been refractory to contemporary chemotherapy, suggesting that there is likely to be a role for this modality of treatment.77,78 However, its use requires familiarity with proper techniques for infusion pump placement and care. In addition, patients receiving HAI chemotherapy must be closely monitored for signs of biliary sclerosis. Like metastases, cholangiocytes of the biliary tree also derive their blood supply from the hepatic arterial system; as a result, prolonged arterial infusion of chemotherapy can result in biliary strictures. Administration of dexamethasone in conjunction with FUDR has been found to mitigate this risk.

The “Disappearing Metastasis”

Because of the risk of chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity, patients with advanced disease undergoing preoperative systemic chemotherapy must undergo serial imaging surveillance so that operative intervention can be undertaken before the onset of liver damage. On occasion, follow-up imaging will identify a complete radiographic disappearance of tumor(s). Appropriate management of the “disappearing metastasis” remains controversial. It is evident that a majority of these tumors have simply become radiographically occult, but will eventually reappear and progress after discontinuation of chemotherapy.79 Interestingly, longitudinal analyses suggest that a subset of as many as one-fifth of highly selected patients may have durable remission of “disappeared metastases.”80,81 However, it is also noteworthy that most of these patients will eventually shows signs of disease progression elsewhere, attesting to the significant risk of eventual relapse among patients with aggressively advanced hepatic colorectal metastases.

Prognostic Factors

A number of investigations have sought to identify the patient and disease variables that influence outcomes after hepatic metastasectomy. A prognostication system that has been shown to be of some utility is the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Clinical Risk Score, which is a simple 0 to 5 scoring system incorporating the presence (or absence) of five prognostic variables related to both the primary and metastatic disease ([1] node-positive primary cancer, [2] disease-free interval [between the time of primary and metastatic cancer diagnosis] <12 months, [3] carcinoembryonic antigen >200 ng/mL, [4] maximal hepatic tumor size >5 cm, and [5] multifocal [>1] hepatic tumors). Developed prior to the introduction of contemporary chemotherapeutic regimens, the Clinical Risk Score has been shown to be useful for stratifying patients in terms of their risk of developing recurrent disease.82 However, recent analyses have suggested that, in the modern era of highly effective systemic therapy, the dominant variables influencing outcomes after hepatic metastasectomy may be tumor responsiveness to chemotherapy and technical resectability.83 This suggests that modern chemotherapy has largely overcome the impact of such traditional prognostic factors as nodal positivity and disease-free interval, largely reducing the decision of whether to undertake surgical intervention to a technical determination of resectability.

The goal of operative therapy is a margin-negative resection. However, the optimal distance of margin clearance remains unclear. As hepatic resections become more aggressive in their efforts to clear multifocal tumors while preserving a maximal amount of hepatic parenchyma, the ability to consistently obtain widely negative resection margins has become more difficult. Interestingly, recent analyses suggest that the critical goal is simply the presence of a microscopically negative margin, with relatively little prognostic impact being associated with the actual distance of margin clearance.84–86

Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy

It is difficult to compare SBRT clinical outcomes with those observed after resection primarily because the SBRT series generally include patients who have been heavily pretreated with systemic therapy for metastatic disease and are, therefore, further along in the disease history. In most of the early liver SBRT pilot trials, an assortment of primary histologic types of cancers were included, though the most common is generally colorectal cancer by virtue of its frequency among cancer types. In 2006, Hoyer and colleagues87 reported a phase 2 study of SBRT for patients with limited metastatic colorectal cancer. While the trial included patients with metastatic disease in a variety of sites, the majority (44/64 patients) had liver metastases, alone or in combination with other sites.87 The 45-Gy dose was prescribed to the isocenter and not to the periphery of the tumor, and thus the actual dose received by the periphery of the tumor was likely close to 30 Gy in three fractions. The treatment was administered without the use of daily CT-based image guidance. Over half the patients had received prior chemotherapy, and roughly one-third had had prior surgery or RFA. The 2-year actuarial lesion local control rate was 86%, and the 1-year survival was 67%. One patient died due to hepatic failure possibly related to treatment, and another had surgery for colonic perforation. The toxicity observed was otherwise generally mild.

In 2011, Chang and colleagues88 reported a pooled experience of liver SBRT restricted to colorectal cancer metastases from three major institutions collected prospectively on prospective clinical trials at each institution. Sixty-five patients with 102 lesions treated from August 2003 to May 2009 were analyzed. The patients were heavily pretreated: 47 (72%) patients had had one chemotherapy regimen prior to SBRT and 27 (42%) patients had had two or more regimens. Daily image guidance was used in all cases; only two patients experienced any late grade 3 toxicity, and none had any grade 4 or 5 toxicity. Local control of individual lesions was correlated with total dose and either of two composite equivalent dose indices taking into consideration the number of fractions and fraction size. When the data were fit to a logistic tumor control probability curve, the dose required to expect ≥90% local control was on the order of 48 Gy or higher in three fractions. On multivariate analysis, active extrahepatic disease was associated with worse overall survival, and the attainment of durable local control was also closely correlated with longer survival. The results support the contention that even for heavily pretreated patients, clearing or cytoreducing the burden of tumor in the liver is associated with longer survival.

Evaluating local control after SBRT requires an understanding that there will be changes on CT scans whereby transiently for a few months after treatment, a hypodense region will be seen that correlates to the volume of liver that received a dose above the threshold to cause local veno-occlusive change, and this region is typically larger than the treated tumor.89

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree