Summary of Key Points

- •

Knowledge of the anatomy of the mediastinum is critical to establishing the differential diagnosis and choosing the best diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

- •

A wide variety of possible etiologies must be considered including solid and lymphatic malignancies, benign cysts, and benign neoplasms.

- •

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential tools for the diagnosis and planning of surgical approach and choice of surgical technique.

- •

Thymoma and lymphoma are common anterior mediastinal masses in adults. Lymphoma and benign cysts are the most common middle mediastinal lesions. Neurogenic tumors are seen only in the posterior mediastinum.

- •

Vital visceral, vascular, and neurologic structures exist in the mediastinum, and precise surgical technique is paramount to avoid complications.

- •

Surgical resection of benign cysts should be reserved for bronchogenic or esophageal cysts; pericardial cysts do not warrant invasive tissue sampling or removal.

- •

Bronchogenic and esophageal cysts can acquire significant adhesions to surrounding structures, making minimally invasive resection challenging in some patients.

- •

Electrocautery should be used with caution near the spinal foramina to avoid central nervous system injury.

- •

Known complications from surgery include phrenic nerve injury and paralysis, chyle leak, bronchial or esophageal perforation, and bleeding.

The mediastinum is the region of the thorax between the pleural cavities, commonly described in three compartments: anterior, visceral or middle, and posterior. The anterior mediastinum contains the thymus, lymph nodes, connective tissue, and fat. The visceral mediastinum contains the heart and its vasculature within the pericardium, trachea and proximal bronchi, esophagus, thoracic duct, lymph nodes, and the vagus, phrenic, and recurrent laryngeal nerves. The posterior mediastinum contains the sympathetic chain and proximal intercostal arteries, veins, and nerves. The differential diagnosis for a mediastinal mass is influenced by its anatomic position ( Table 54.1 ).

| Anterior | Middle | Posterior |

|---|---|---|

| Thymoma | Lymphoma | Neurogenic tumor |

| Teratoma, seminoma | Pericardial cyst | Bronchogenic cyst |

| Lymphoma | Bronchogenic cyst | Enteric cyst |

| Carcinoma | Metastatic cyst | Xanthogranuloma |

| Parathyroid adenoma | Systemic granuloma | Diaphragmatic hernia |

| Intrathoracic goiter | Meningocele | |

| Lipoma | Paravertebral abscess | |

| Lymphangioma | ||

| Aortic aneurysm |

Mediastinal masses are often asymptomatic and present as an incidental finding during workup, surveillance, or screening for an unrelated condition. Malignant disease is more likely to be symptomatic. Symptoms resulting from local compression and invasion include superior vena cava syndrome, dyspnea, dysphagia, hoarseness, cardiac tamponade, and Horner syndrome. Systemic symptoms may occur because of endocrine tumor activity or fever, chills, and weight loss associated with malignancy ( Table 54.2 ). Certain syndromes have commonly associated tumors and symptoms, including myasthenia gravis and anterior mass with thymoma or café-au-lait spots and posterior mass with von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis.

| Syndrome | Tumor |

|---|---|

| Myasthenia gravis, red blood cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, Good syndrome, Whipple disease, megaesophagus, myocarditis | Thymoma |

| Multiple endocrine adenomatosis, Cushing syndrome | Carcinoid, thymoma |

| Hypertension | Pheochromocytoma, ganglioneuroma, chemodectoma |

| Diarrhea | Ganglioneuroma |

| Hypercalcemia | Parathyroid adenoma, lymphoma |

| Thyrotoxicosis | Intrathoracic goiter |

| Hypoglycemia | Mesothelioma, teratoma, fibrosarcoma, neurosarcoma |

| Osteoarthropathy | Neurofibroma, neurilemoma, mesothelioma |

| Vertebral abnormalities | Enteric cysts |

| Fever of unknown origin | Lymphoma |

| Alcohol-induced pain | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Opsomyoclonus | Neuroblastoma |

The most common anterior mediastinal masses in adults are thymoma, germ cell tumor (GCT), lymphoma, and displaced thyroid. In the visceral compartment, the most common mass is lymphadenopathy associated with metastatic disease. Other visceral masses are usually congenital cysts. Most posterior masses are neurogenic tumors.

CT can provide information about the size, density, and anatomic relationship of mediastinal masses. Intravenous contrast medium used with CT will usually assist in the definition of mediastinal masses. MRI of the mediastinum is hindered by cardiac and respiratory motion artifacts. MRI of mediastinal masses is normally reserved for assessing intraspinal involvement of paravertebral tumors.

Germ Cell Tumors

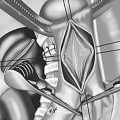

Extragonadal GCTs result from errors in cell migration during embryogenesis ( Fig. 54.1 ). These tumors are most commonly found in the mediastinum, where they account for 15% of anterior mediastinal masses in adults. Most mediastinal GCTs present in the second through fourth decade of life. Approximately 85% of mediastinal GCTs are benign and occur at similar rates in men and women; however, 90% of malignant GCTs occur in men. With malignant GCTs, scrotal ultrasound is necessary to detect possible primary gonadal tumors. Histologically, there are three types of GCTs: benign teratoma, seminoma, and nonseminomatous GCT (NSGCT).

Benign Teratoma

Benign teratomas are composed of multiple germ cell layers, and are also referred to as mature teratomas. These teratomas may contain any type of tissue, including teeth, hair, bone, cartilage, and occasionally higher order structures. Although many patients will be asymptomatic, benign teratomas have the capacity to compress, erode, rupture, and fistulize into surrounding structures. Rarely, these benign tumors undergo malignant transformation. Elevated serum levels of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) may indicate malignant GCT. Total surgical excision of benign teratoma is recommended. The treatment approach for benign teratomas can vary and has included median sternotomy and lateral thoracotomy. The preferred treatment, particularly with GCTs, is the hemiclamshell approach, which is a unilateral extension into the hemithorax. For large masses with bilateral extension, a clamshell incision (a combined upper median sternotomy and anterior thoracotomy) provides excellent exposure. Benign teratomas are often adjacently adherent, which can make dissection challenging, and total resection is not always possible. However, postsurgical prognosis is excellent, even with incomplete excision. There is no indication for chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Seminoma

Seminomas occur almost exclusively in men and usually present in the third to fourth decade of life. Seminomas often grow quite large before discovery, and metastatic disease is present in 60% to 70% of cases. The serum AFP level is normal in pure seminoma and the beta-hCG level can be elevated in some patients. An elevated AFP level implies a nonseminomatous component, but workup and treatment should be the same as for NSGCTs; however, a CT-guided needle biopsy should be considered over surgical biopsy. Because of the prevalence of systemic disease, treatment with radiotherapy alone is associated with significantly lower progression-free survival compared with that associated with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin chemotherapy. Even in the case of a residual mass, there is little, if any, role for surgical interventions.

Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumor

NSGCTs can include embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, or a mixed histology. Primary mediastinal NSGCT appears to be biologically distinct from testicular NSGCT and is associated with a poor prognosis. Primary mediastinal NSGCTs grow rapidly and metastatic disease is found in 80% of patients. Overall survival after multimodality treatment is 40% to 50%. Hematologic malignancies present with NSGCT in 6% of cases, most commonly in patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome is the most common. The serum AFP level is elevated in 80% of patients and the beta-hCG level is elevated in 30% to 35%. Substantial elevation of tumor marker levels can preclude biopsy. However, if biopsy is performed, fine-needle aspiration can be ambiguous and is discouraged in favor of core-needle biopsy or anterior mediastinotomy.

The standard treatment for NSGCT is four courses of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; ifosfamide has been recommended over bleomycin to avoid pulmonary complications prior to surgical resection. Residual mass after chemotherapy should be surgically resected, regardless of the serum marker levels; the prognosis is poor for patients with unresectable residual masses. When active germ cell cancer is present in the surgical specimen, two additional courses of chemotherapy should be given. Patients who have no residual tumor should be followed closely with history and physical examination, determination of serum markers, and CT. Patients who have disease recurrence have a particularly poor prognosis, although a small number of patients may benefit from salvage chemotherapy. A 20% survival rate following surgical resection for relapsed primary mediastinal NSGCT has also been reported.

Lymphoma

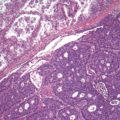

Lymphomas represent a variety of hematologic neoplasms. Proper management of lymphoma depends on subtyping and staging. Approximately 15% of mediastinal masses are lymphomas, typically in the anterior or middle compartment ( Fig. 54.2 ). About 90% of mediastinal lymphomas represent disseminated disease, and one-third are Hodgkin lymphomas. Most patients present with some combination of systemic B symptoms, and symptoms associated with local compression. Positron emission tomography is frequently used to stage and monitor the progress of lymphoma.

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Mediastinal involvement occurs in as many as two-thirds of Hodgkin lymphoma. Diagnosis typically requires tissue quantities only obtainable by surgical biopsy. Typically, video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) or anterior mediastinotomy will yield definitive samples; however, mediastinoscopy is not always sufficient. CD15- and CD30-positive Reed-Sternberg cells, which are diagnostic for Hodgkin lymphoma, can be difficult to identify in a small biopsy. Disease is staged according to the Ann Arbor Staging System; early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma is treated with chemoradiation therapy and late-stage disease is treated with chemotherapy only.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Large B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma are the most common forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the mediastinum. As in Hodgkin lymphoma, a sizable biopsy sample is often required for diagnosis. However, lymphoblastic lymphoma is usually first identified in bone marrow and peripheral blood; thus a mediastinal biopsy is not necessary. Lymphoblastic lymphoma is particularly aggressive, and treatment with chemotherapy and possible bone marrow transplant should not be delayed by staging procedures. Large B-cell lymphoma is treated with chemotherapy, and some centers also use radiotherapy for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree