Fig. 23.1

Lymphoscintigraphy, frontal and lateral view. Injection site in the left breast and sentinel node in the left axilla clearly visible already after 5 min

Fig. 23.2

Sentinel node stained with patent blue, afferent and efferent lymph vessels also stained

There is no standard for the amount of radioactive tracer to be injected. More than 40–60 MBq is not needed. A higher dose is used if the injection is given the day before any surgical intervention. The volume of vital blue dye injected has varied widely in the range of 0.5–5 ml.

The type of tracer used differs, depending on the availability in different countries. The use of both a vital dye and a radioactive tracer results in a higher detection rate and lower rate of false-negative findings.

Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy can be performed for mapping of sentinel nodes. In most instances this is not necessary [20], especially if one is interested only in the presence of a sentinel node in the ipsilateral axilla. A handheld detection probe is sufficient for identification of the radioactive node. However, in cases of previous operations to the breast or axilla, when distortion of the lymphatic drainage is often present, a lymphoscintigram can be of help to identify nodes outside the axilla.

Recently, alternative substances for mapping of sentinel nodes have been used. Thus, the use of superparamagnetic iron oxide (Sienna+®) combined with a magnetic probe (SentiMag®) has been developed as a nonradioactive alternative. Initial validation studies have shown results similar to those of the conventional techniques [21, 22]. Indocyanine green is another vital fluorescent dye that can be used for detecting sentinel nodes. It requires a special infrared light to be used in the operating field to identify the node and produces virtually the same detection rates as conventional methods [23, 24]. A recent development for spatial mapping of the sentinel node is the use of a hybrid single-photon emission computed tomography camera with integrated CT (SPECT/CT) [25], which can help the surgeon to find nodes in unusual anatomical locations. Finally, radioactive seeds and microbubbles have also been used. However, the results were disappointing and a planned large study was abandoned [26].

Detection rates in recent studies (when participating surgeons are familiar with the technique) are generally high at 97–98%, irrespective of the tracer used. The major drawback of vital dyes is their ability to induce serious allergic reactions. Handling of radioactivity is highly regulated and controlled by several legislative restrictions, and because of the short half-life of the isotope, a nuclear medicine department is necessary in or near the hospital, to be able to use the substance. This limits the availability of the method to larger hospitals in developed countries. The use of paramagnetic Sienna+® nanoparticles could overcome these obstacles and might prove a useful method in the future. The technique is not without problems; however, nonferrometalic instruments must be used during surgery, and the injected substance may be retained in the breast tissue for lengthy periods which may cause discoloration and, more importantly, MRI artefacts.

23.1.5 Surgery

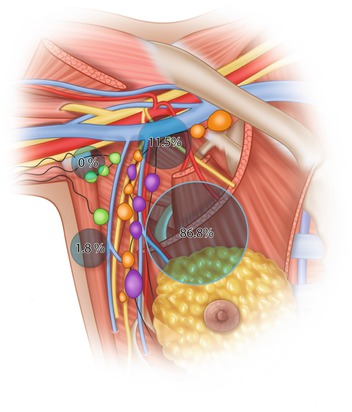

The surgical procedure for removal of the sentinel node is often simple and straightforward. A short incision is placed either in the lower hairline of the axilla or above the area where the probe indicates the highest radioactivity. Careful blunt dissection is performed towards the radioactive node. If a blue dye has been used, a blue-stained lymph vessel can usually be identified and followed to a blue node. The sentinel node is most often located in the lower medial part of the axilla alongside the lateral thoracic vein, below the second intercostobrachial nerve (87%) or above the nerve (11.5%), but rarely lateral in the axilla (1.8%) (see ◘ Fig. 23.3) [27]. After harvesting of the first sentinel node, the probe is used to search for additional radioactive nodes. As a rule of thumb, not based on solid evidence, nodes with 10% or more of the activity measured in the first sentinel node are often also regarded as sentinel nodes and removed. Also, any additional blue nodes and any suspicious hard and enlarged nodes should be removed and sent for histopathology. It is seldom necessary to remove more than 4–5 nodes.

23.1.6 Indications for SLNB

Indications for SLNB are summarized in ◘ Table 23.1. and will be discussed further in the section below concerning accuracy of the procedure.

Table 23.1

Indications for SLNB

Condition | Remark |

|---|---|

T0–T2 tumour | SLNB recommended |

T3 tumour | SLNB useful, but fewer patients can be spared ALND |

T4 tumour and inflammatory cancer | ALND still standard procedure |

DCIS – mastectomy and GIII | SLNB recommended |

DCIS GI–II or breast-conserving surgery | Refrain from SLNB |

Multicentric/multifocal tumour | SLNB recommended but slightly higher FNR reported |

Previous breast operation | SLNB recommended with lymphoscintigraphy |

Previous SLNB | New SLNB recommended |

Previous ALND | SLNB can be tried, but lower detection rate expected |

Neoadjuvant treatment | SLNB recommended before start of treatment in cN0 patients |

Neoadjuvant treatment | SLNB after treatment controversial, low detection rate, high FNR |

Old age | SLNB recommended |

Obesity | SLNB recommended |

Pregnancy | SLNB can be used, low dose to foetus, avoid blue dye |

23.1.7 Accuracy of SLNB

The accuracy of SLNB is dependent on several factors. There is a certain learning curve for the method, but it is brief, and the vast majority of breast surgeons can use this method after a few cases. The anatomical drainage system of the breast has both superficial and deep pathways. As mentioned above, the depth of injection may influence the drainage pattern, but even after standardized superficial injections, different pathways have been seen, so there is an inbuilt possibility that the sentinel node identified during the operation might be falsely without metastasis, whereas some other nodes might contain metastases. This results in a false-negative rate (FNR) for SLNB and is the major disadvantage of the procedure. The true FNR of the procedure is probably in the range of 5–7%, but this is based on figures from early validation studies and might be lower in trained hands [28].

The SLNB approach has been applied to most types and stages of breast cancer. It is feasible for small non-palpable tumours [29]. Injection of tracers can be done after preoperative marking of the index tumour (stereotactically or by ultrasound), if an anatomical association is sought, or under the areola. This group of patients gains the greatest benefit from the procedure, because metastases are rare, and most patients do not need an ALND. SLNB also works for large [30] and multifocal tumours [31], even if the proportion of patients who do not need axillary clearance is lower in this group. In patients who have undergone previous breast surgery, the lymphatic drainage may be distorted, but the technique may still be feasible [32, 33]. Because of a less predictable drainage pattern, a preoperative lymphoscintigram is of help for detecting sentinel nodes outside the ipsilateral axilla. A sentinel node in the opposite axilla is seen in 3–4% of cases previously treated for breast cancer [34].

In patients with recurrent breast cancer, previous surgical procedures have most often included some interference with the axilla. In cases of a previous SLNB, a new SLNB can be performed without any expected problems. Even in cases where a formal axillary lymph node clearance has been done, a SLNB can be attempted [35, 36]. A higher rate of non-detection should be expected, and in such cases, individual assessment has to be done and discussed beforehand with the patient: whether to refrain from clearing the axilla once again or to explore it. In cases where a negative sentinel node can be retrieved, the results are as accurate as for surgery-naïve patients. In cases of a positive node, individual assessment should be done and the risks and benefits of clearance discussed with the patient.

The role of SLNB in the context of primary systemic therapy is still unclear [37]. When primary systemic therapy is planned, a SLNB may be recommended before the start of treatment in patients with a clinically negative axilla. The FNR for SLNB in this group of patients is at the same level as SLNB in cases not planned for primary systemic therapy, which means that ALND may be avoided. If there is a suspicion of lymph node involvement at the preoperative workup, fine-needle aspiration or core-needle biopsy is recommended; but if they are negative, SLNB can be used for staging. In patients who have completed primary systemic therapy, more than one-third and up to a half have pathologically node-negative disease at the time of surgery [38] and require no further axillary treatment. The German SENTINA trial studied the detection rates and FNR for SLNB both before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) [39]. It found that the detection rate was lower after NAC, especially if a first SLNB had been performed before starting treatment. They also found a high FNR when SLNB was performed after treatment. The SENTINA trial did not study the FNR in sentinel node-negative cases before NAC, as they did not do ALND in all patients after NAC. In a nationwide Swedish study with 220 patients, the FNR was 7% (Frisell personal communication). The use of SLNB after NAC has been the subject of lively debate. A recent meta-analysis of published data showed a lower detection rate and higher FNR than for SLNB performed in patients undergoing primary surgery [40]. The American Alliance study, ACOSOG Z1071 [41], designed to determine the FNR in patients with node-positive breast cancers before the start of treatment – subject to the SLNB and at least two nodes examined after chemotherapy – found a FNR greater than 10%, which was higher than the predetermined limit of acceptability. Thus, the results did not support the use of SLNB after neoadjuvant treatment as an alternative to ALND. However, an Italian study with 5-year follow-up after SLNB in patients who had received primary systemic therapy showed excellent overall survival among those whose tumours converted from cN1/N2 to cN0 after treatment and very few axillary recurrences [42]. These results suggest that SLNB is acceptable for patients who become cN0 after primary systemic therapy.

SLNB should not be performed in cases of true ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [43–45]. However, in many instances the diagnosis before operation is based on a core biopsy, and in 10–25% of cases, invasive areas are found on definitive pathology workup after the operation [46, 47]. A retrospective Swedish study showed that neither the size nor the histological grade of DCIS was correlated with the risk of metastases in the sentinel node and that in most cases a SLNB can be avoided except if mastectomy is performed [48]. It is therefore recommended that SLNB should only be considered for patients with large areas of high-grade DCIS when mastectomy is performed.

23.1.8 Intraoperative and Pathological Analysis of the Sentinel Node

Intraoperative analysis of the sentinel node has been used widely, to enable the surgeon to proceed to immediate axillary clearance in case of a positive finding (metastases in the node). In the past, this was highly desirable when the goal of sentinel node mapping was to identify patients without metastases who did not need any axillary clearance and those with metastases in the era when this always mandated clearance. Today, not all node-positive patients will be subjected to clearance, so the need for immediate results from the biopsy is less important.

The examination of frozen sections is probably the most frequently used intraoperative assessment. It is reasonably quick and inexpensive and available at most institutions. The sensitivity depends on the number of sections processed and the type of metastasis. Frozen section can be used to identify almost 100% of patients with macrometastases, but is less sensitive in identification of micrometastases or isolated tumour cells [49, 50]. Adding immunohistochemical (IHC) staining to frozen sections in combination with conventional haematoxylin-eosin staining slightly increases the detection of micrometastases [51]. In a few institutions, serial sections have been used perioperatively and have been claimed to be almost 100% sensitive [52]. However, both serial sectioning and IHC consume both time and resources and are not used at many sites.

Imprint cytology is quick but with less accuracy than frozen sections [51, 53]. Automated evaluation with the use of one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) has been developed and is in use in numerous institutions globally. It measures cytokeratin 19 mRNA in homogenized sentinel nodes and quantifies the copy number. Three levels are identified: no metastases, micrometastases and macrometastases. The method is sensitive in detecting positive nodes. However, some criticism has been raised against the method because of its low positive predictive value, leading to overdiagnosis of macrometastases, that would have been classified as micrometastases using conventional histopathology [54].

Postoperative workup is not standardized worldwide, but many local guidelines exist. Serial sectioning would be the ideal method, but it is time consuming and expensive. The primary goal is to detect macrometastases, which is done by taking sections every 2 mm. If they are found, then no further sectioning is needed, whereas if micrometastases or no metastases are found, additional sections at 200 μm should be taken. Routine IHC is not recommended in most guidelines, but might be of value, especially in cases of lobular cancers which may be otherwise missed. Any pathology report should include a description of the size of metastases and the number of affected nodes. Metastases are classified into macrometastases >2 mm, micrometastases 0.2–2 mm and isolated tumour cells (ITCs) if <0.2 mm (see ◘ Figs. 23.4, 23.5, and 23.6).

Fig. 23.4

Histologic section of a lymph node containing macrometastatic deposits routine staining

Fig. 23.5

Histologic section of a lymph node containing micrometastatic deposits, routine staining

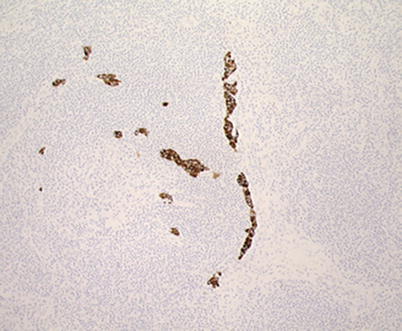

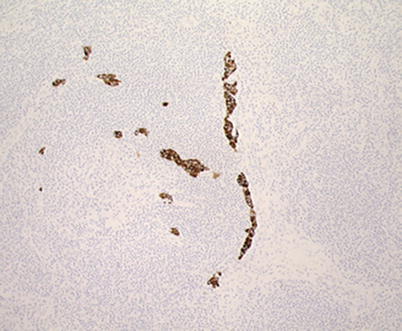

Fig. 23.6

Histologic section of a lymph node containing isolated tumour cells, immunohistochemical staining

23.1.9 Morbidity After SLNB

One of the motives for the concept of SLNB aims to diminish the side effects of the axillary staging procedure. Conventional axillary clearance is associated with a high risk of permanent complaints from the shoulder region and arm, including lymphedema [2]. SLNB has been shown to cause fewer problems. The ALMANAC trial, a British randomized study, designed to compare arm morbidity and quality of life between patients undergoing SLNB and ALND, showed a significantly lower incidence of arm morbidity (oedema 5% vs. 13% and sensory loss 11% vs. 31%, respectively) [55] and a better quality of life [56]. These results were repeated in a randomized Italian study [57] and have been confirmed in review articles and meta-analyses [2]. However, SLNB is not free from side effects. In an Italian study, patients with small breast cancers without lymph node metastases on preoperative ultrasound were randomized to SLNB or simple observation. Patients in the observation arm had significantly less disability in the early postoperative period than those subjected to SLNB [58].

A prospective Swedish study included 550 patients treated with either SLNB alone for node-negative patients or with ALND for patients with and without metastases in the axilla. Patients were followed yearly for 3 years, and arm volumes and arm morbidity were recorded. The patients undergoing SLNB alone had a significantly lower risk of arm morbidity and lymphoedema than those who underwent ALND. It seems that extensive axillary surgery per se was associated with arm morbidity [1, 8].

Another important side effect from SLNB is the risk of allergic reaction to the vital dye. Isosulfan blue seems to be a little more prone to evoking an allergic reaction than patent blue. Montgomery and colleagues [59] reviewed almost 2400 SLNB procedures where isosulfan blue had been used and found an incidence of an allergic reaction of 1.6%. Most reactions were mild – urticaria, rash or pruritus – but in 0.5% the reaction caused hypotension sometimes accompanied by bronchospasm. Corresponding figures for patent blue have been calculated among almost 8000 British patients. In total 0.9% of the patients experienced allergic reactions, but only 0.06% had a severe reaction requiring postponement of the planned operation, or needing intensive care [60]. Although most reactions were mild and no deaths have been recorded, both surgeons and anaesthetists should be aware of the possibility of a severe reaction, and patients should be supervised accordingly after any injection of a vital dye. There is also the problem of blue discoloration of the breast which may be unsightly and persist for many months.

No allergic reactions have been reported as a result of superparamagnetic iron oxide, but the substance has a tendency to leave a brownish discoloration in the skin of the breast for a long time after superficial injections. The tracer might also stay in the breast for a long time and interfere with subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

23.1.10 Evidence Base for Clinical Decision-Making After SLNB

There are numerous follow-up studies showing that the risk of axillary recurrence after a negative sentinel node biopsy and no further axillary dissection is very low [61–64]. Most of the studies included in the reviews were relatively small with a short follow-up time. However, the Italian study by Galimberti and colleagues [64] reported on 5262 sentinel node-negative patients with 7 years of follow-up and found a 1.7% axillary recurrence rate and a 91.3% 10-year survival rate. Likewise, the latest follow-up of the Swedish Multicentre Cohort Study showed an isolated axillary recurrence rate of 1.6% after a median follow-up time of 10 years of 2216 patients with negative SLNB findings and no further axillary dissection [65] and a breast cancer-specific survival at 10 years of 94.3% and overall survival of 85.4%. Moreover, OS and DFS after a negative SLNB and no axillary dissection were excellent in a large randomized study, and no difference was found between those who had an axillary clearance and those who had not [66]. Omitting axillary clearance after a negative SLNB is therefore regarded as safe and should be the routine standard of care.

Further surgical management of the axilla, when tumour deposits are found in the sentinel node, depends on the extent of node involvement. The relevance of ITC findings is unclear. They could be transient cells without the potential to grow to manifest metastases, or they could be the first appearance of a true metastasis. In most studies, no prognostic importance has been ascribed to ITC findings [67–69], so patients with ITC should be regarded as node negative. This means that no further axillary surgery is needed, and decisions on adjuvant medical and radiological treatment should be based on primary tumour characteristics, not on ITC findings.

The prognostic value of micrometastases has been debated extensively, but recent evidence suggests that they are potentially hazardous [68, 70], and the patients should be handled as if they were node positive in terms of systemic treatment. However, the benefit of axillary clearance when only micrometastases are found is doubtful. Galimberti and colleagues randomized 931 patients to either clearance or follow-up after SLNB showing micrometastases. After 6 years of follow-up, no differences in DFS or OS rates were seen; in fact, those patients who did not undergo axillary dissection did a little better [71]. The recommendation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology is to refrain from axillary clearance when micrometastases are identified [44]. However, the long-term effects on survival after omission of axillary lymph node clearance are still unknown.

The standard of care for patients with macrometastases has long included axillary clearance. However, the development of new effective drugs for adjuvant treatment, together with an increasing proportion of screen-detected cancers, has led to a questioning of the need for this procedure. The long-term results from the NSABP-04 study, randomizing patients to radical mastectomy or total mastectomy without axillary clearance with or without postoperative radiotherapy, failed to show any difference between the arms [72]. An IBCSG-initiated randomized study showed no difference in survival or recurrence after 5 years, comparing tamoxifen treatment without axillary clearance to axillary clearance among patients older than 65 years [73]. In cases of minor deposits of macrometastases, many institutions have abandoned axillary clearance, based on one randomized study, ACOSOG Z0011 [74]. In this, 891 patients were randomized to either SLND alone or SLND followed by axillary clearance in cases of one or two positive sentinel nodes. After 6.3 years of follow-up, no differences in DFS or OS were noted. However, most patients in this study were at a low risk of recurrence. All had breast-conserving therapy with postoperative whole-breast irradiation, in many cases including level I of the axilla, and there were many cases with micrometastases included. Only 891 patients were recruited out of the 1900 that should have been included according to a power analysis, and very few events were recorded. Thus, there is still uncertainty about the best treatment approach for patients with node-positive disease. An EORTC study in clinically node-negative patients who had metastases in SLNB randomized patients to ALND or radiotherapy. At 5-year follow-up, there was no difference in the occurrence of axillary metastases but significantly fewer arm symptoms in the radiation arm [75]. As for patients with micrometastases, the long-term results for omission of axillary clearance in patients with macrometastases are still awaited.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree