Although mastectomy is associated with excellent local control in most breast cancer patients, chest wall recurrence (CWR) after mastectomy has been noted in up to a third of cases. Jatoi et al found that breast-conserving surgery was associated with a greater odds of locoregional recurrence than mastectomy in a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials (pooled odds ratio [OR]: 1.561; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.289-1.890), locoregional recurrence still occurred in 8.5% of mastectomy patients.1 CWR rates of up to 40% have been reported depending on primary tumor characteristics and initial treatment.2 Even with the addition of adjuvant systemic therapy, CWR remains a significant issue in a considerable proportion of patients (Table 69-1).

A number of studies have demonstrated that the addition of postmastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) may reduce the rate of CWR by up to 70%.3 Although the British Columbia4 and Denmark studies5,6 were criticized for a variety of reasons, the American Society of Clinical Oncology7 and the American Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology8 have both issued guidelines recommending PMRT in patients with tumors larger than 5 cm or with 4 or more positive lymph nodes. Although PMRT is not recommended for node-negative patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm, PMRT remains controversial in the 1 to 3 positive-node group. The finding of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) that a 20% reduction in 5-year local recurrence risk results in a 5% absolute reduction in 15-year breast cancer mortality may prompt more widespread use of PMRT in these patients.3

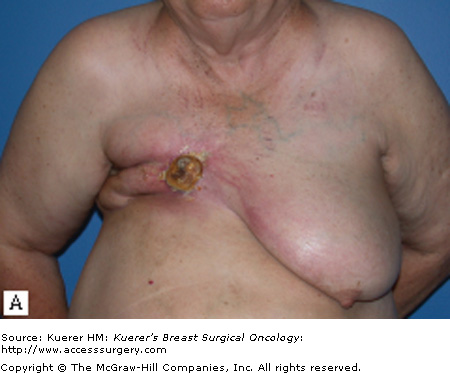

The diagnosis of CWR, defined as a breast cancer recurrence in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or underlying bone after mastectomy, requires a high index of suspicion. Many CWRs occur within 2 to 3 years after mastectomy, but some have been found more than 10 years later. Careful surveillance of the chest wall after mastectomy is therefore required. Although some CWR present as large fungating masses, most are subtle, often presenting with an asymptomatic nodule in the skin or a slight erythematous rash. More than half of all CWR present as a solitary nodule in the skin; the remainder present as multiple nodules or diffuse disease encompassing the chest wall.9 In 23 to 70% of cases, the recurrence involves the previous mastectomy scar.10-12 Because CWRs may be mistaken for foreign body granuloma, fat necrosis, or radiation-induced injury,13 histologic confirmation is required and can be obtained with a punch biopsy.

The finding of a CWR is accompanied by the presence of distant metastases in up to a third of patients.13 Patients who present with an isolated CWR, however, will not uniformly have a grim prognosis. A number of factors are associated with improved prognosis in these patients, and a variety of prognostic tools are available to assist clinicians in predicting survival in these patients.10,14,15

In a study of 130 patients with isolated CWR, investigators from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center found that initial node-negative status, time to CWR more than 24 months, and treatment with radiation therapy for the CWR were independent predictors of improved disease-free and overall survival.15 Patients with all 3 favorable features had a median overall survival of 141 months (10-year actuarial survival: 75.4%), those with 1 or 2 favorable features had a median overall survival of 54 months (10-year actuarial survival: 25.1%), and those without any favorable features had a median overall survival of 16 months (10-year actuarial survival: 0%).15 These data suggest that patients presenting with CWR are a heterogeneous population, and aggressive management using a multidisciplinary approach is warranted in a subset of patients for whom a good prognosis may be anticipated.

Fodor et al similarly found that patients who were initially node negative and who developed a CWR more than 24 months from their initial mastectomy had a better 10-year cause-specific survival.16 In addition, they found that if the recurrence was operable and was a single lesion in the scar, prognosis was improved.

Surgical resection of CWR is an important aspect of the management of patients with CWR because it provides excellent local control in patients with resectable disease. Surgery is particularly useful in patients who have previously had radiation therapy or those in whom radiation therapy is ill advised.

For patients with isolated recurrences involving only the skin or the surgical scar, resection of the CWR is often straightforward. Resection with primary closure is generally feasible and provides excellent local control. With more extensive disease, coverage with either a skin graft (Fig. 69-1) or autologous flap (Fig. 69-2) may be needed. Preoperative consultation with a plastic surgeon should be obtained as part of a multidisciplinary approach. The goal of resection should be the attainment of clear margin. Although there is no consensus on what constitutes a “clear margin,” wide resection is generally recommended.

For patients with CWR extending to underlying bony elements, the utility of resection of ribs and sternum remains controversial. Such extensive resections are often associated with significant morbidity, although some authors have reported reasonable long-term results of full-thickness resections in selected patients (Table 69-2).

With increased use of skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction, there has been some concern regarding the incidence, detection, and management of CWR in this setting. In terms of incidence of CWR, no evidence indicates there is any difference in the local recurrence rates following skin-sparing mastectomy versus conventional mastectomy (Table 69-3). Furthermore, the incidence of CWR does not vary with the type of reconstruction.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree