Classic signs of breast cancer

1. Mass

2. Architectural distortion

3. Malignant-appearing microcalcifications

4. Focal asymmetry

Subtle signs of breast cancer

1. Developing densities

2. Subtle asymmetries

3. Partially visualized abnormalities

4. One-view-only finding

The positive predictive value on a screening examination for masses and calcifications is similar and is slightly lower for developing asymmetry and least for focal asymmetry [1]. Although architectural distortion is the least common of the four frequent signs of breast cancer, its reported positive predictive value for breast cancer on a screening examination (10.2 %) is similar to masses (9.7 %) and calcifications (12.7 %) and higher than for developing asymmetry (7.4 %). Focal asymmetry has a relatively low PPV for breast cancer at 3.7 %. A mass with spiculated margins (PPV = 81 %) and linear calcifications (PPV = 81 %) had the highest predictive value among 225 cancers in a series of 492 cases undergoing surgical biopsy. Other mammographic features that also show a high positive predictive value for cancer include masses with an irregular shape (73 %) and calcifications in a segmental (74 %) or linear distribution (68 %) [3].

Mass

A mass is a space-occupying lesion that is seen in two different mammographic projections. It has an outwardly convex border, is seen on two views, and is at least as dense centrally as in the periphery. Summation shadows on the other hand are produced by fortuitous superimposition of fibroglandular tissue and are not visualized in more than one projection [4]. When a mass is identified on a screening mammogram, an analysis of its features is done as follows: The shape of the mass is described as being round, oval, or lobular when a mass has an undulating contour. If a mass cannot be described as one of these, it is described as having an irregular shape (Fig. 5.1a–c). Once the primary features are ascertained, recall for a diagnostic assessment is often initiated. Spot compression views help define the margin characteristics of a mass. A margin that is sharply demarcated and well defined in at least 75 % of its extent and remainder is obscured is considered circumscribed with an abrupt transition from the mass to the surrounding tissue. Small undulations of the border of a mass are defined as a macrolobulated border. A poor definition of the margin is suspicious for infiltration, a finding suggestive of malignancy. When lines radiate from the edge of a mass, the margin is described as being spiculated [5]. A mass with a density higher than of the surrounding fibroglandular parenchyma is more likely to be malignant than a low-density mass (Fig. 5.2a–c). In a retrospective study of 348 breast masses with biopsy confirmation, 70.2 % of the high-density masses were malignant, and 22.3 % of the iso- or low-density masses were malignant [6]. Similar results have been reported using inductive logic programming and conditional probabilities and validating this association in an independent dataset [7].

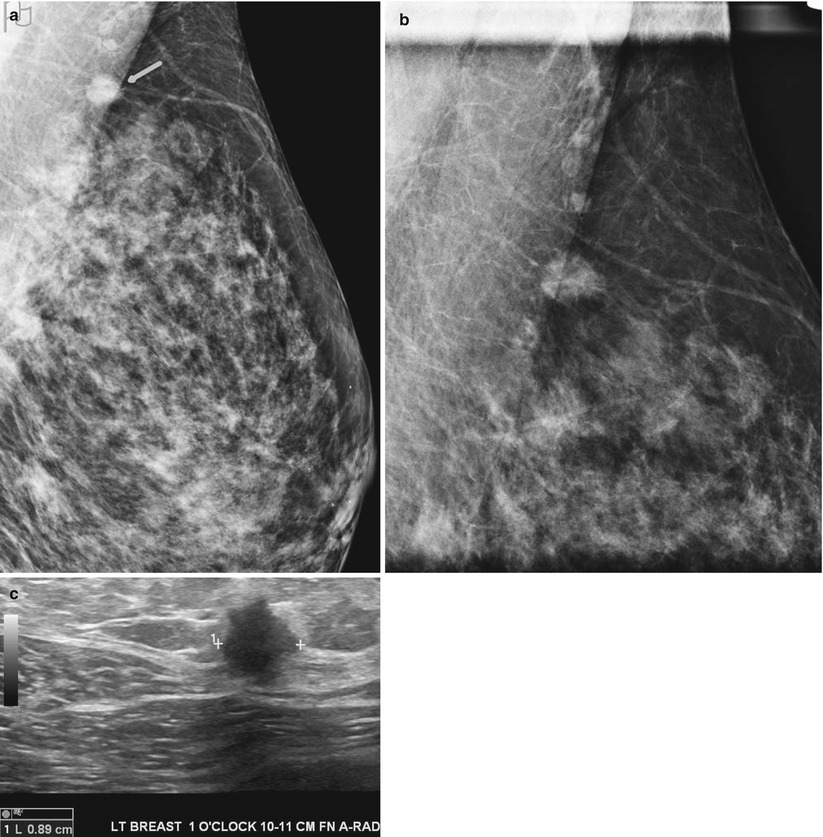

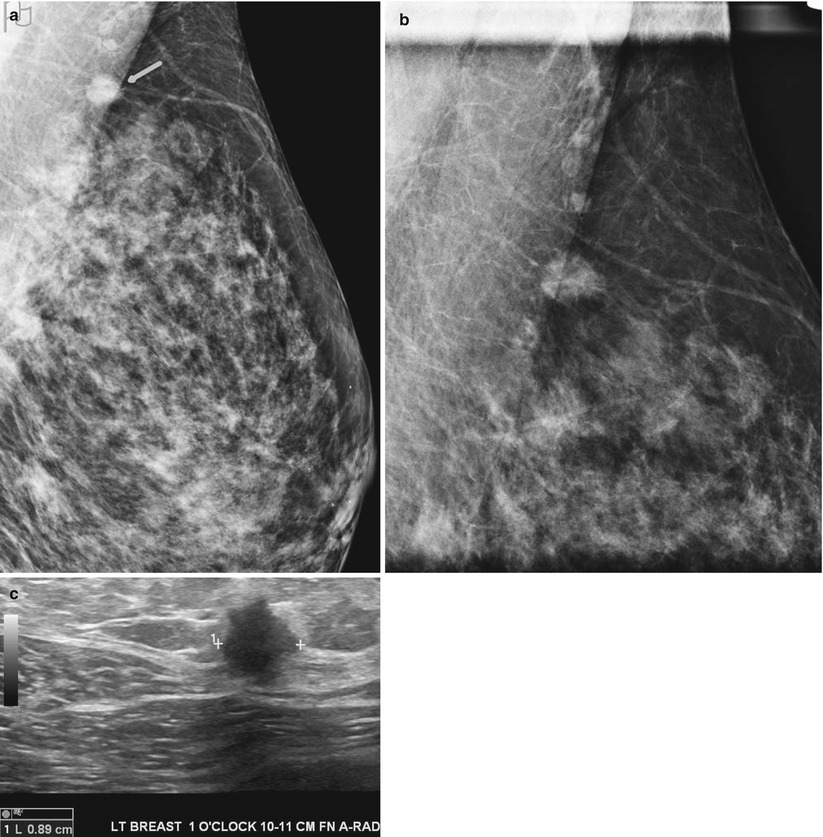

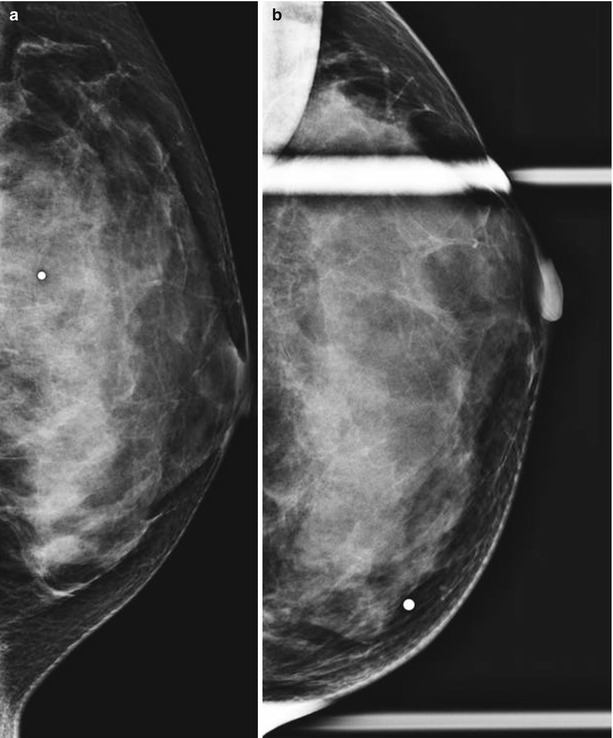

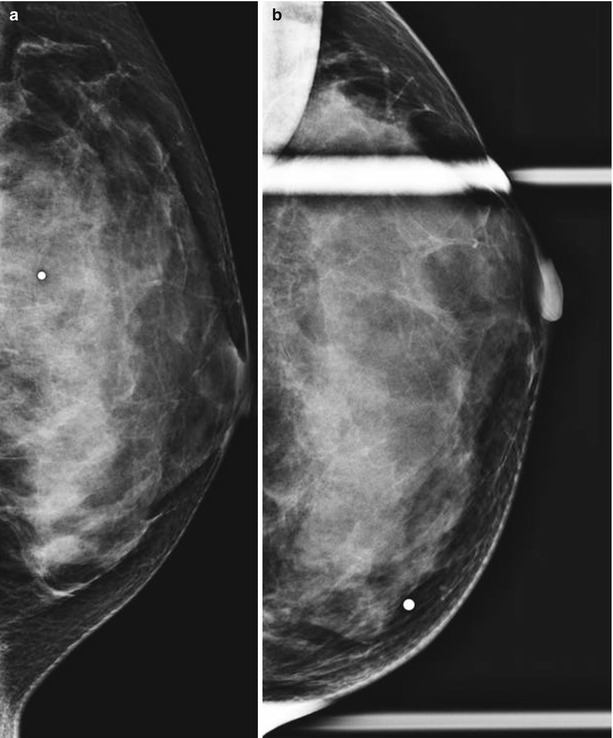

Fig. 5.1

(a–c) A 47-year-old with a 9 mm mass histologically proven to be a DCIS. (a) Mediolateral oblique view of a screening mammogram demonstrates a dense mass in the axillary tail (arrow). (b) Spot compression view in the mediolateral oblique projection reveals a mass with fine spiculated borders suspicious for a malignant mass. (c) Ultrasound demonstrates a 9 mm irregular mass with malignant features

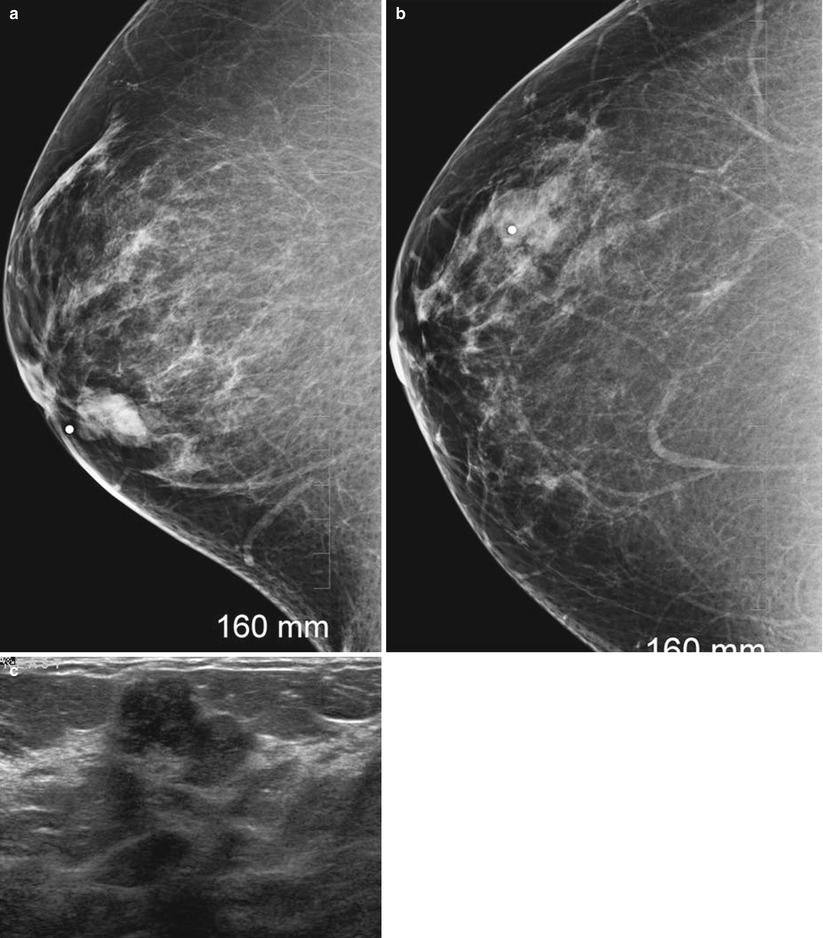

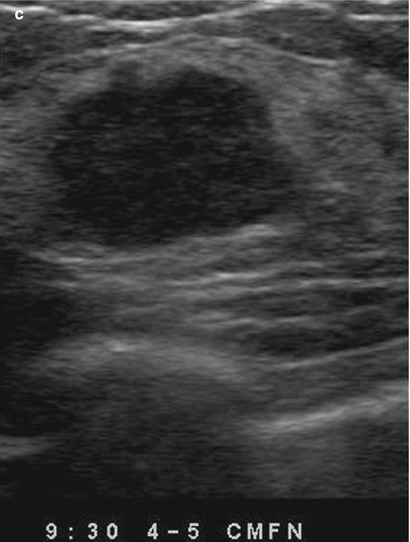

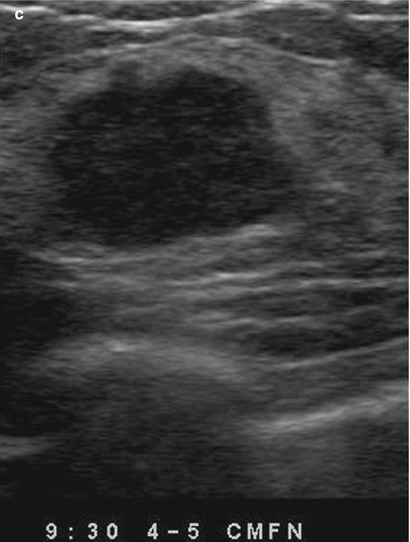

Fig. 5.2

(a–c) A 31-year-old with a palpable mass histologically proven to be invasive ductal cancer. (a) Mediolateral oblique view demonstrates a hyperdense mass with a circumscribed margin. (b) Craniocaudal projection reveals the mass with obscured borders. (c) Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic lobulated solid mass with ill-defined margins

There is a reported association between morphologic features and tumor stage and prognosis. Masses with spiculated margins are known to be associated with lower-grade tumors and hence have a better prognosis (Fig. 5.3a, b). On the other hand triple-negative breast cancers have been found to be associated with circumscribed masses and masses with microlobulations and with ill-defined borders. Lymphovascular invasion has been reported to be seen more often in breast cancers associated with architectural distortion rather than those with spiculated mass. The reason behind this association is unknown [8]. Lymphovascular invasion is also more common in masses with calcifications. In invasive cancers, the presence of calcifications is often associated with extensive intraductal component and necrosis. In one series breast cancers presenting as architectural distortion were reported to have positive margins in 65 % of cases. These investigators, however, did not find a significant correlate between mammographic features and tumor differentiation or ER (estrogen receptor)/PR (progesterone receptor) status [8].

Fig. 5.3

(a, b) A 48-year-old with a screen-detected small spiculated mass histologically proven to be an invasive ductal cancer. (a) Spot compression magnification mediolateral view demonstrates a spiculated mass with microcalcifications and a second area of pleomorphic microcalcifications superiorly (arrow) that was proven to be DCIS. (b) Spot compression magnification craniocaudal view demonstrates a spiculated mass with microcalcifications

It is known that the proportion of invasive cancers tends to be higher in younger women (Fig. 5.4a–c). The ratio of invasive to noninvasive cancers increased from 1:1 in those younger than 50 years of age to 3:1 in those over 70 years. Breast cancers presenting with calcifications are also decreased from 63 % in women younger than 50 years to 26 % in older than 70 years [2]. Generally calcifications that are malignant are associated with DCIS in 63 % of cases, whereas a spiculated mass is associated with invasive cancer in as high as 95 % of cases [9]. In a small percentage of cases, spiculated masses may represent pure DCIS or DCIS associated with a radial scar, 8 % of a series of 86 lesions with predominant DCIS in one series [10]. The prognosis is best and 8-year survival was the longest for small spiculated masses [95 %] that are 1–9 mm and good for rounded masses [91 %] compared to those presenting with calcifications [77 %]. Patients with casting or pleomorphic calcifications had significantly worst prognosis [11].

Fig. 5.4

(a–c) A 35-year-old with a palpable lump in left breast histologically proven to be invasive ductal cancer. (a) Mediolateral oblique view reveals no abnormality. (b) Craniocaudal view with spot compression demonstrates dense tissue but no mass. (c) Ultrasound demonstrates a solid hypoechoic mass with ill-defined and microlobulated borders suggestive of malignancy

Architectural Distortion

Architectural distortion refers to a localized disruption of the breast architecture which can include spiculations or thin lines that radiate from a focal point or a localized retraction of the edge of the parenchyma at its interface with fat. It is a normal finding to see lines randomly crossing within the breast parenchyma; what is abnormal is when one sees these lines converging to a focal area. Not uncommonly overlapping crisscrossing tissue lines may simulate architectural distortion on a screening mammogram. Careful inspection alone with use of a magnifying lens may suffice to make this assertion; when unclear, recall for spot compression and rolled views of the breast in the projection where it is best seen will help to exclude an area of true architectural distortion (Fig. 5.5a, b). Architectural distortion when unassociated with other findings such as masses or clustered calcifications can be often subtle and accounts for a significant number of missed breast cancers; a discussion on missed cancers appears later. Architectural distortion is less common than a mass as a mammographic sign of breast cancer but is highly predictive of breast cancer both at screening and diagnostic mammography [1]. Architectural distortion is a sign of invasive ductal and invasive lobular cancer and results from the fibrosis in a scirrhous carcinoma. Ductal carcinoma in situ most commonly manifests as indeterminate or malignant-appearing microcalcifications. However, a small percentage of DCIS can appear as areas of distortion, 2.1 % [4/190] in one series [12]. Architectural distortion in an area of DCIS is often attributed to associated sclerosing adenosis rather than due to the in situ cancer itself. In one series, 5 of 54 cases of DCIS [10.8 %] appeared as an area of architectural distortion. Histopathological correlation in this series showed that the AD in 4 of 5 cases correlated with sclerosis in the interstitium around DCIS, and DCIS in Cooper’s ligament accounted for the appearance of AD on the mammogram [13].

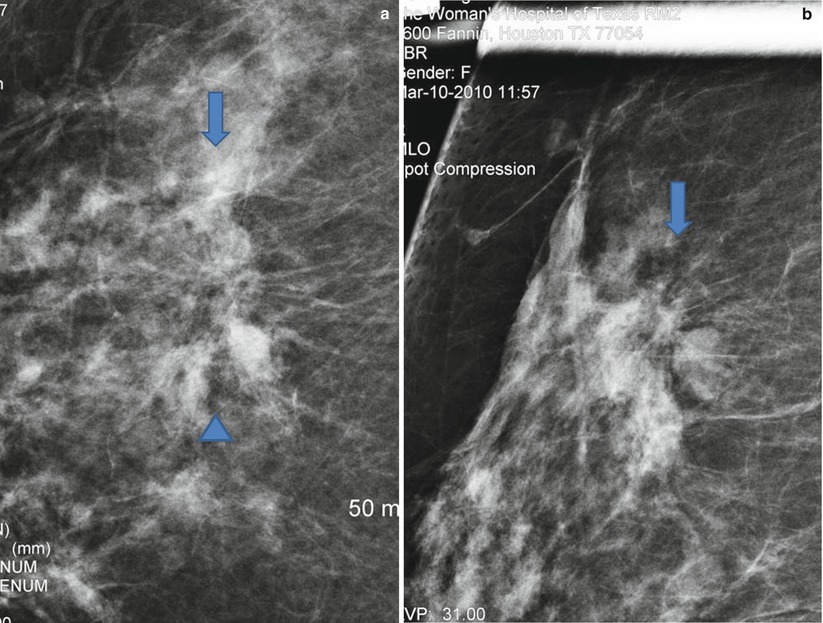

Fig. 5.5

(a, b) An invasive ductal cancer appearing as an area of architectural distortion. (a) Spot compression magnification views in the CC projection demonstrates an area of subtle architectural distortion (between arrow and arrowhead). (b) Spot compression magnification views in the MLO projection demonstrate an area of subtle architectural distortion (arrow)

It is also known that in patients with architectural distortion on mammography, there is more likely to be positive margins than those with masses or calcifications [2]. Breast cancer presenting as AD is also reported to be significantly larger than that seen on mammography compared to other mammographic abnormalities. It is therefore recommended that in those patients with nonpalpable architectural distortions, a wider excision be undertaken to minimize the risk of having positive margins. Although most series of invasive breast cancers have found architectural distortion a less common mammographic presentation, architectural distortion has been reported to be more frequently seen in invasive lobular cancer. Architectural distortion was found to be the second most common appearance after a mass, in some studies ranging from 10 to 34 % of cases of invasive lobular cancer [14]. The differential diagnosis of an area of architectural distortion appears in Box 5.2. A finding of an architectural distortion on a mammogram except for those that can definitively be attributed to prior surgery, biopsy, or trauma is an indication for excisional biopsy in most instances. Known mimics of cancers that can appear as areas of architectural distortion include a radial scar and sclerosing adenosis.

Box 5.2 Differential Diagnosis of Architectural Distortion on a Mammogram

1. Invasive ductal and invasive lobular cancer |

2. Radial scar |

3. Sclerosing adenosis |

4. Postsurgical or post biopsy |

5. Post breast trauma |

Differential Diagnosis of Architectural Distortion

Radial Scars

A radial scar is a known mammographic mimic of breast cancer. When these lesions are smaller than 1 cm, they are referred to as a radial scar and when larger than 1 cm are called complex sclerosing lesions (Fig. 5.6a–d). Mammographic features that are typical of radial scars include the presence of a central lucency from which thin long spicules radiate. The abnormality has a characteristic varying appearance on different projections and radiolucent linear structures parallel the spicules. Such a mammographic appearance has been called the black star in contradistinction to cancer where the central area of architectural distortion is dense and hence is referred as a white star. Radial scars are not typically palpable and not associated with microcalcifications [15, 16]. The mammographically described radial scar is distinct from those that are incidentally reported in histology specimens in about 28 % of cases [17]. These latter radial scars are small lesions, mammographically occult, and do not carry an increased risk of associated cancer.

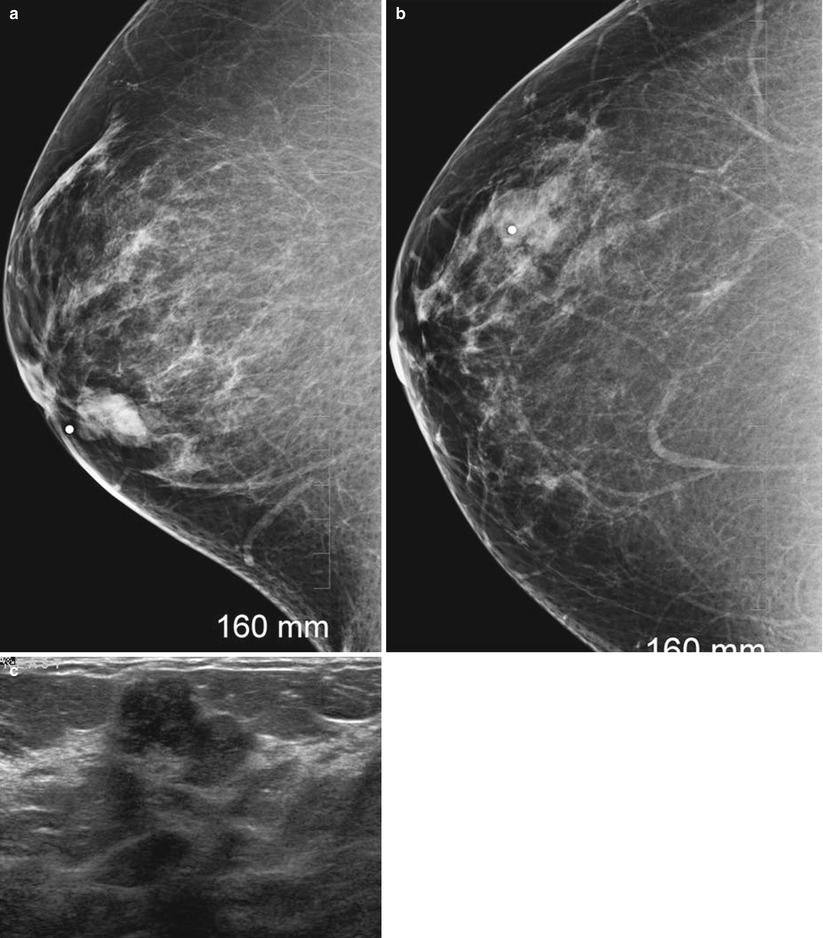

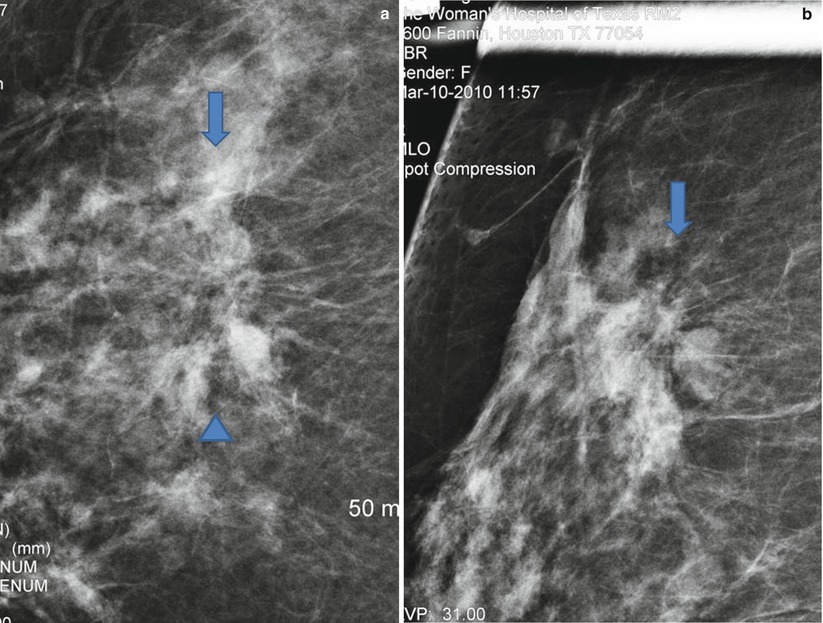

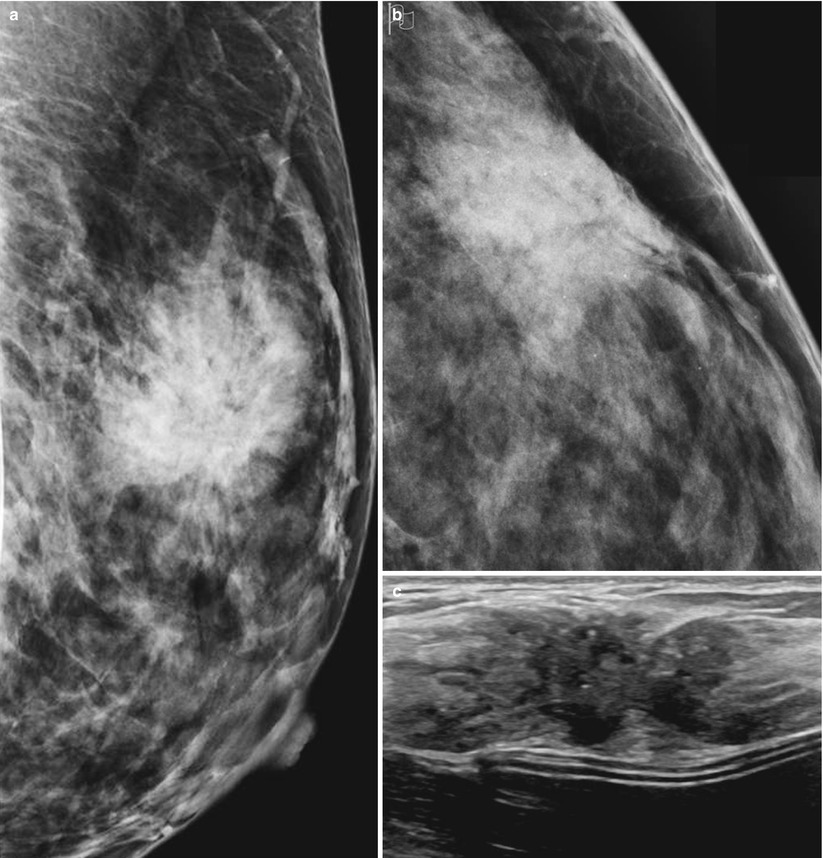

Fig. 5.6

(a–d) A 35-year-old with a family history of cancer and a palpable lump histologically proven to be a complex sclerosing lesion. (a) Mediolateral oblique view demonstrates a large irregular focal asymmetry with architectural distortion. (b) Craniocaudal view demonstrates a large irregular focal asymmetry with architectural distortion. (c, d) Ultrasound demonstrates an irregular mass that was considered probably malignant

The reported incidence of radial scars on screening mammograms is about 3 per 1,000 [18]. Although benign, when suspected on a mammogram, excisional biopsy is generally recommended due to the known association with invasive cancer and the difficulty in distinguishing tubular cancer from radial scar on core biopsy specimens [19]. Sonography is generally not performed when a radial scar is identified on the mammogram; however, sonographic appearance of radial scars has been described. Ultrasound is useful when the area of distortion is seen on one view only and if seen may then be used for presurgical localization [20–22].

Sclerosing Adenosis

Sclerosing adenosis is a proliferative benign abnormality characterized by proliferation of stromal and myoepithelial cells leading to distortion of the acini. It is often associated with other benign and malignant abnormalities. When sclerosing adenosis exists as a dominant component, it may appear as a localized area of calcifications, mass, focal asymmetry, or an area of architectural distortion [23]. In one series of 69/76 cases of histologically proven sclerosing adenosis that were mammographically detectable, 12 % appeared as areas of localized architectural distortion [24]. In another series of 43 cases, 6.9 % [3/43] of sclerosing adenosis appeared on the mammogram as an area of architectural distortion [25].

Breast Trauma

Trauma to the breast may lead to mammographic findings that mimic cancer; however, appropriate history and evolution of changes in the appearance are helpful in the differential diagnosis (Fig. 5.7a, b). The spectrum of trauma encompasses blunt trauma such as in a seat belt injury, all types of breast biopsy, lumpectomy, as well as mammoplasty. Fat necrosis that can result from any insult to the breast parenchyma may also present diagnostic dilemma particularly when a reliable history is not present. A description of the postoperative breast appears in a separate chapter (Chap. 16).

Fig. 5.7

(a, b) A 44-year-old with a history of a seat belt injury 3 months prior to a screening mammogram. (a) Mediolateral oblique view demonstrates an area of asymmetry and distortion in upper breast. (b) Spot compress view in the craniocaudal projection shows the area of distortion

Fat necrosis is a clinical and imaging mimic of breast cancer. The mammographic spectrum of findings includes a lipid cyst with or without calcification of the wall, clustered microcalcifications, spiculated mass, and nonlucent focal mass. Fat necrosis may result from accidental breast trauma or any of the previously listed causes of iatrogenic breast trauma, surgery, and biopsy [26]. Seat belt injuries cause appearance of areas of fat density necrosis and areas of increased density in a band-shaped distribution. In the short term the increased density may decrease in size, and the line of fibrosis is evident. These changes evolve over a period of time with development of calcifications and resultant architectural distortion [27].

Microcalcifications

Calcifications that are identified on a screening mammogram and that do not exhibit the established criteria of benign calcifications are recalled to undergo a diagnostic mammogram. Spot compression magnification views in the mediolateral and craniocaudal projections are routinely obtained. The rationale for obtaining magnification views is to study the morphology and the distribution pattern of the calcifications. Magnification mammography decreases noise and improves image sharpness allowing for optimal evaluation of the morphology and distribution of calcifications. A description of mammographically identified calcifications should include the morphologic features and the distribution of the calcifications. Macrocalcifications are typically larger than 2 mm and are associated with benign processes; microcalcifications are smaller than 0.5 mm and can be associated with ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive cancer [28]. In DCIS the tumor grows within the duct, distending it but remaining within the basement membrane.

Malignancies presenting as calcifications on mammography are most commonly associated with DCIS and have been reported in up to 68 % of cases of ductal carcinoma in situ [2]. About 29–47 % of breast cancers appear as microcalcifications without a mass [1]. About 24 % of the suspicious calcifications are associated with DCIS. Microcalcifications in DCIS are most commonly linear, linear branching, and fine pleomorphic, in a linear distribution. Other forms described in DCIS include the dot-dash pattern, consisting of round and needle-shaped calcifications.

The histological high-grade carcinoma or comedocarcinoma tends to be associated with linear, branching, and irregular calcifications that are in a linear or segmental distribution, formerly referred to as casting type of calcifications. These cancers may also be associated with pleomorphic or amorphous type of calcifications. In comedocarcinoma there is significant necrosis within the lumen of the duct that is involved with cancer. About 90 % of high-grade DCIS is associated with microcalcifications. The lower-grade or noncomedo DCIS is associated more often with clustered calcifications of amorphous or coarse heterogeneous morphology calcifications. Overall unlike the high-grade DCIS, the low-grade DCIS is less frequently associated with microcalcifications and reported in about 50 % of cases. Sometimes in DCIS one sees clustered fine pleomorphic or coarse heterogeneous calcifications, and these are often associated with necrotic tumors of the cribriform or micropapillary type [28]. The differential diagnosis for linear calcifications includes two important benign causes, secretory calcifications and vascular calcifications. Linear calcifications can be associated with benign secretory disease of the breast; these calcifications are often bilateral, regional, and seen in older women. When confined to a smaller region and unilateral, secretory calcifications are a challenge, these tend to be dense and have smooth margins [29]. Vascular calcifications when patchy and confined to one wall of a vessel may appear as a linear calcification. Magnification views help to identify the true nature of these benign vascular calcifications.

There have been reports attempting to correlate the appearance of microcalcifications with likelihood of invasive cancers [30]. In malignant calcifications without a focal mass, invasive foci are more likely when calcifications were larger than 11 mm and with linear calcifications than with granular calcifications [30]. Invasive cancers presenting as calcifications are often associated with high-grade DCIS and are also more likely to be Her2/Neu [human epidermal growth factor receptor 2]-negative cancers [2]. Invasive ductal cancers may also be associated with fine pleomorphic calcifications (Fig. 5.8). Invasive lobular cancer on the other hand is rarely associated with microcalcifications.

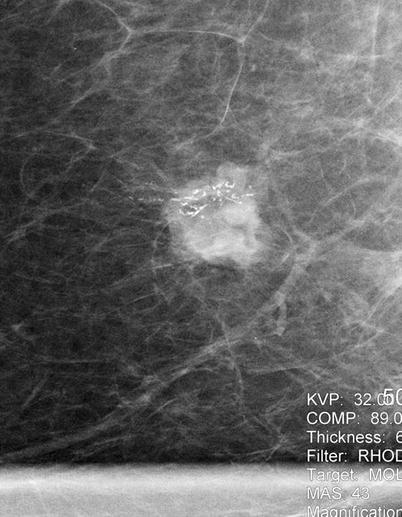

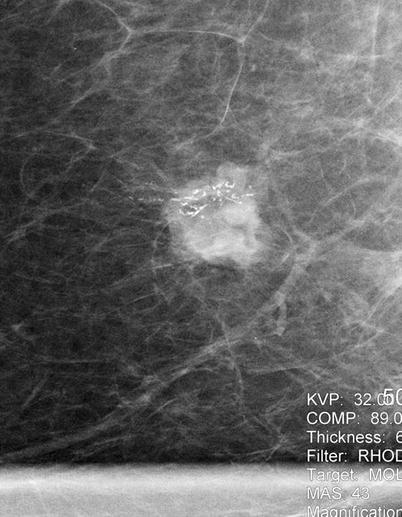

Fig. 5.8

A 67-year-old with histologically proven invasive ductal cancer in the right breast. Spot compression magnification view demonstrates linear branching pleomorphic calcifications associated with an irregular mass

The morphologic types of calcifications that are suspicious for malignancy can be categorized as those with intermediate concern for cancer and those that have a higher probability of being associated with breast cancer [5] (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

Morphology and distribution of calcifications and degree of concern

Benign | Intermediate concern | High probability for cancer |

|---|---|---|

Diffuse, regional distribution | Grouped distribution | Linear, segmental distribution |

Dystrophic, eggshell | Amorphous | Linear |

Secretory, vascular | Granular | Linear branching |

Vascular, sutural | Coarse heterogeneous | Pleomorphic |

Intermediate Concern for Malignancy

1.

Amorphous or indistinct calcifications are small and hazy in appearance; a specific morphologic classification cannot be given. The distribution of such calcifications determines degree of suspicion, when diffuse and scattered are benign, however when seen on a baseline mammogram magnification views are generally obtained. When these types of calcifications have a regional, linear, or segmental distribution, they are considered suspicious and an indication for biopsy.

2.

Coarse heterogeneous calcifications are irregular and larger than 0.5 mm and tend to be clustered. Such calcifications may be associated with malignancy and are also seen in benign lesions such as fibroadenomas, fibrosis, and trauma and in dystrophic calcifications.

Higher Probability of Malignancy

1.

Fine pleomorphic: These are calcifications smaller than 0.5 mm and are more clearly defined than the amorphous type and are irregular with varying sizes and shapes.

2.

Fine linear or fine-linear branching calcifications: These are thin linear or curvilinear irregular calcifications which may be discontinuous and smaller than 0.5 mm. This is suggestive of filling of the lumen of a duct by cancer cells (Fig. 5.9a, b).

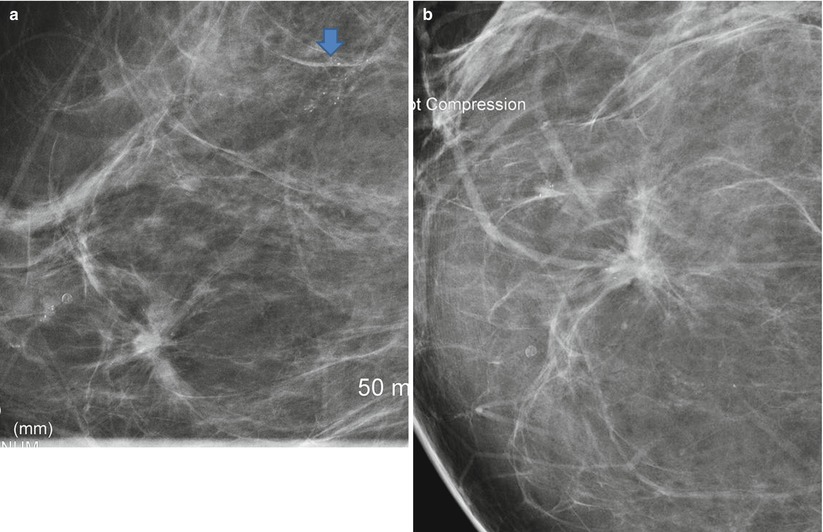

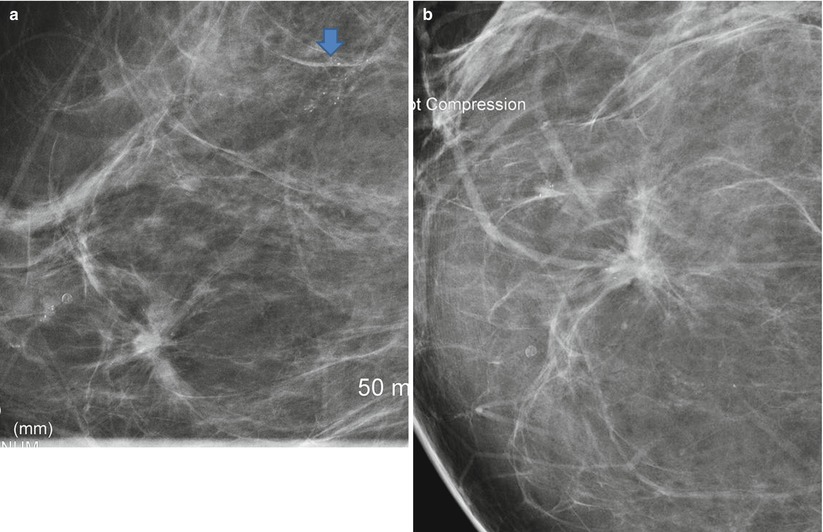

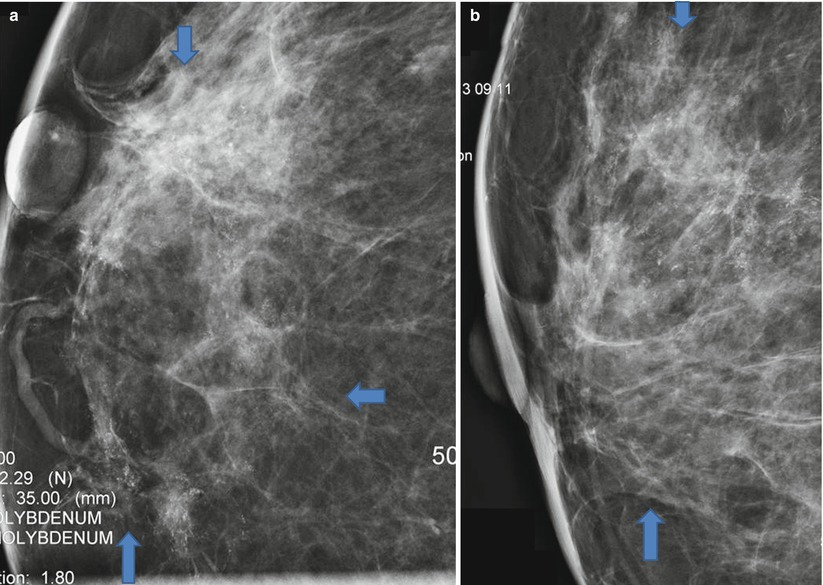

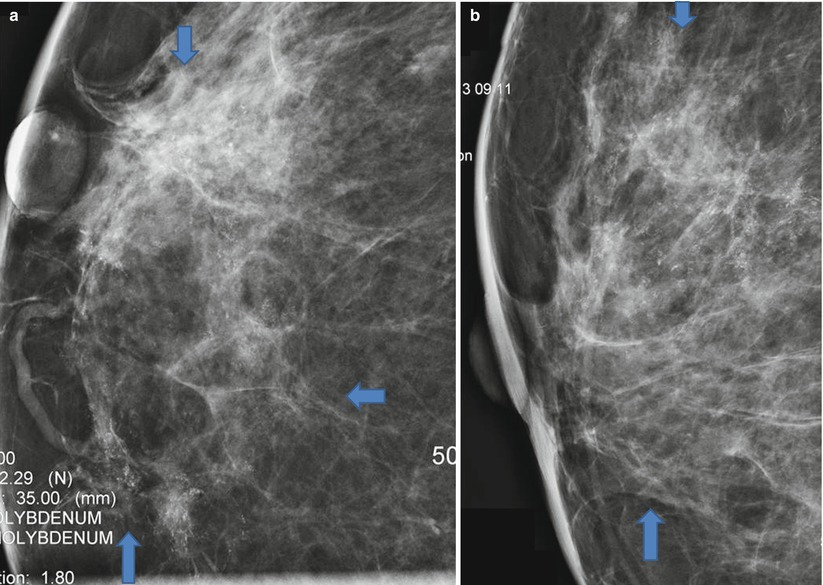

Fig. 5.9

(a, b) A 53-year-old with extensive calcifications identified on a screening mammogram histologically proven to be DCIS. (a) Spot compression magnification views in the craniocaudal projection demonstrate linearly arranged clusters of microcalcifications in a segmental distribution extending to the nipple. (b) Spot compression magnification views in the mediolateral projection demonstrate linearly arranged clusters of microcalcifications in a segmental distribution extending to the nipple. Area of microcalcifications is outlined by arrows

Distribution of Calcifications

The distribution of calcifications is also an additional indicator of the likelihood of calcifications being associated with breast cancers:

1.

Diffuse and scattered calcifications are usually benign particularly when bilateral. Such a distribution is often seen with punctuate and amorphous calcifications.

2.

Regional calcifications may involve most of a quadrant or more than a single quadrant and do not conform to a duct distribution. Such a distribution is generally indicative of a benign etiology although careful assessment of the morphology may modify final assessment and the need for biopsy. Intermediate and high probability morphology even in such a distribution should prompt biopsy.

3.

Grouped or clustered calcifications are when five or more calcifications are seen in a small volume of breast tissue. These are generally considered suspicious.

4.

Linear distribution is when calcifications are arrayed in a line; such a distribution is highly suspicious for cancer and suggests that calcifications are intraductal.

5.

Segmental distribution of calcifications implies calcifications in ducts and their branches and may imply extensive or multifocal breast cancer in a lobe or segment of the breast. Except in the case of coarse rodlike calcifications in older women associated with secretory calcifications, segmental distribution is worrisome and should prompt a biopsy.

Focal Asymmetry

Focal asymmetry is a localized area of increased density that is visible as a confined asymmetry with similar shape in two views, but does not fit the criteria of a mass and lacks defined borders. In majority of cases it represents an island of normal breast tissue especially when there is interspersed fat. Focal asymmetry that is associated with a palpable finding, architectural distortion, or microcalcifications is worrisome for malignancy [5, 31]. Breast asymmetry is generally a result of localized distribution of fibroglandular parenchyma and unlike a mass tends to have concave borders and is interspersed with fat and not dense centrally like one sees in a mass. To appreciate breast asymmetry views of each breast are inspected side by side as is standard practice of viewing mammograms. There are four types of breast asymmetry described [32]:

Asymmetry of the breast is seen in one of two standard mammographic views, formerly referred to as a density. The likelihood of malignancy is slightly less than 2 %; nevertheless, Sickles rightly points out that it is not appropriate to categorize such findings as probably benign since 80 % of these asymmetries can be identified as summation artifact at screening or on additional evaluation and do not require short interval follow-up. The likelihood of malignancy for the remainder lesions is significantly higher [10.3 %], and thereby short interval follow-up is not justified [32, 33].

Global asymmetry is when there is substantially more tissue in one breast compared to the other and occupies at least one quadrant of the breast. When not associated with a palpable abnormality, this finding is benign, and when associated with a palpable finding, a small percentage (3 %) may be associated with breast cancer [34].

Focal asymmetry lacks convex borders of a mass and occupies less than one quadrant of the breast. The likelihood of malignancy for such a finding that is not associated with a mass, palpable finding, architectural distortion, calcifications, and sonographic correlate and with no prior mammograms to assess stability is less than 1 %.

A developing asymmetry is a focal asymmetry that is new or enlarging or denser when compared to prior mammogram (Fig. 5.10a–g). Unlike such developing focal asymmetry, hormone-induced developing asymmetry is bilateral and global. Infection, trauma, and surgery are other nonsuspicious causes of a developing asymmetry that can be excluded by clinical history [31]. Developing asymmetry is an uncommon finding and reported in 0.16 % of 180,801 screening mammograms and 0.11 % of 27,330 diagnostic mammograms. On a screening examination, the incidence of cancer in a developing asymmetry has been reported to be 12.8 %, and in those that are persistent after a diagnostic work-up, irrespective of the presence of a correlative physical finding, the reported cancer rate is as high as 26.7 % [35]. Therefore, an uncomplicated developing asymmetry that is persistent after a diagnostic work-up unless proven to be due to benign finding such as a cyst by ultrasound should be categorized as a BI-RADS 4 with a recommendation for biopsy. A normal ultrasound does not preclude recommendation for a biopsy. In one series of 300 nonpalpable cancers, 6 % were manifest as developing asymmetry [36].

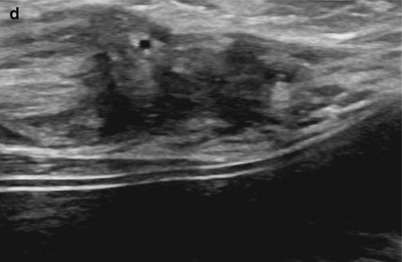

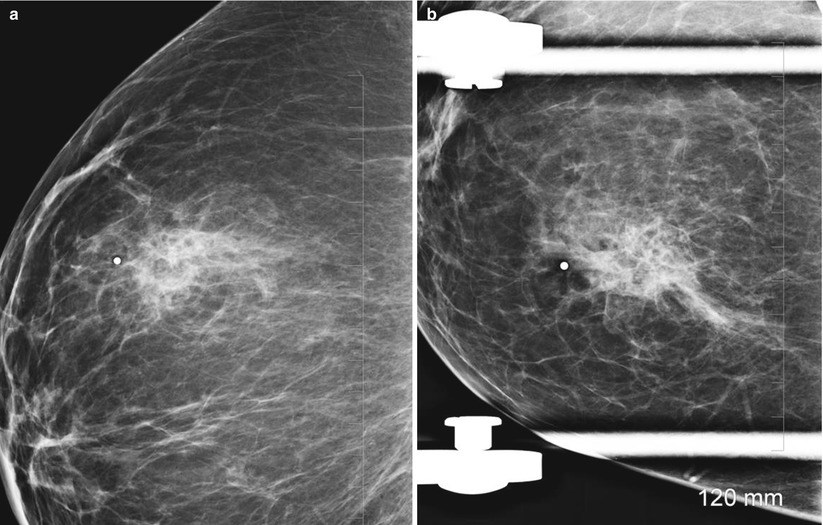

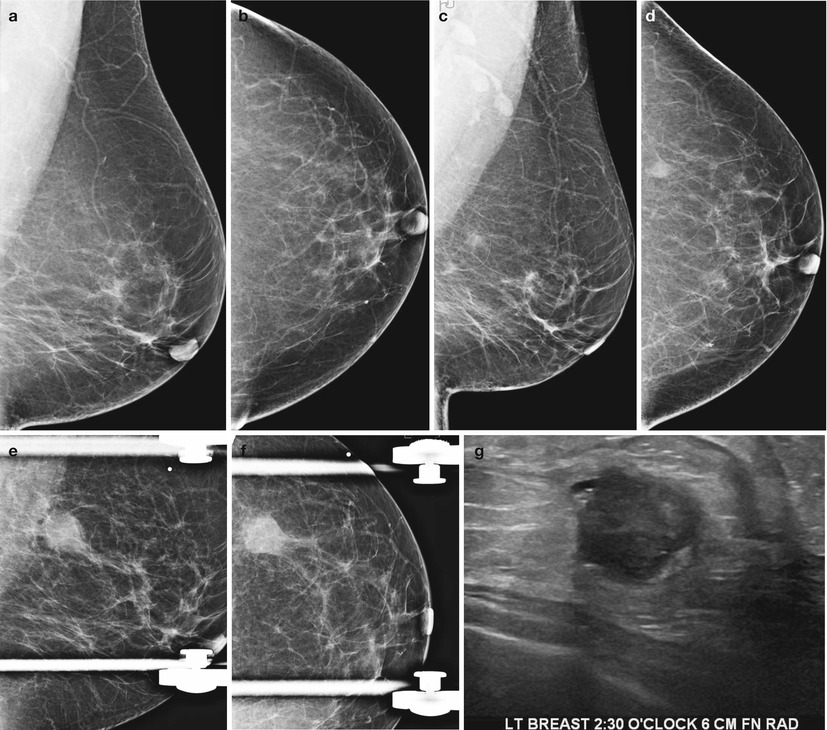

Fig. 5.10

(a–g) A 55-year-old with a new developing asymmetry that was subsequently proven to be invasive ductal carcinoma. (a) Left breast mediolateral oblique view obtained in August 2011 demonstrates a fat-replaced breast parenchymal pattern with no abnormal findings. (b) Left breast craniocaudal view obtained in August 2011 demonstrates no abnormal findings. (c) Left breast mediolateral oblique view obtained in August 2012 demonstrates a developing asymmetry in the posterior outer central breast. (d) Left breast craniocaudal view obtained in August 2012 demonstrates a developing asymmetry in the posterior outer central breast. (e) Spot compression mediolateral oblique view obtained in February 2013 demonstrates a high-density irregular mass in the posterior outer central breast. Patient had failed to return for a recommended diagnostic mammogram in August 2012. (f) Spot compression craniocaudal view obtained in February 2013 demonstrates a high-density irregular mass in the posterior outer central breast. (g) Ultrasound shows a solid mass with malignant features

Sonography is an appropriate work-up for a focal asymmetry that is persistent mainly to exclude an underlying mass. In one series sonography had a negative predictive value for breast cancer of 89.4 % (7/9 cancers detected). One palpable focal asymmetry without a sonographic correlate proved to be an invasive ductal cancer as did one without a palpable correlate. A negative sonography should not preclude biopsy in those with a palpable focal asymmetry. However, the presence of localized hyperechoic tissue matching an area of focal asymmetry is suggestive of a benign process [37]. See Fig. 5.11a–d.

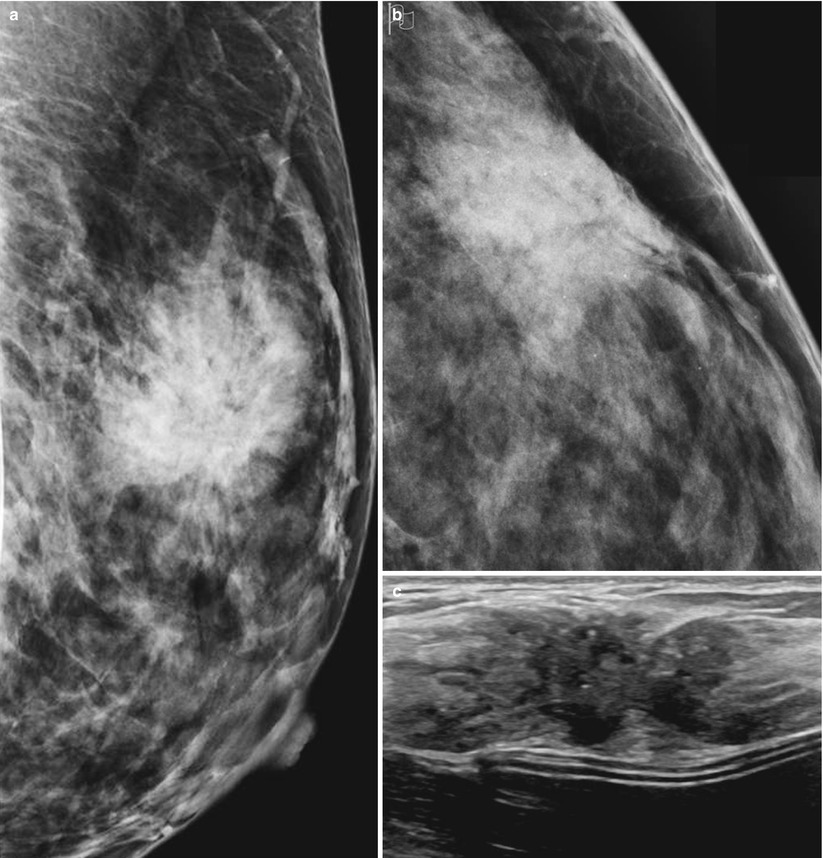

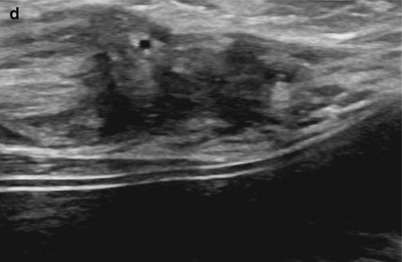

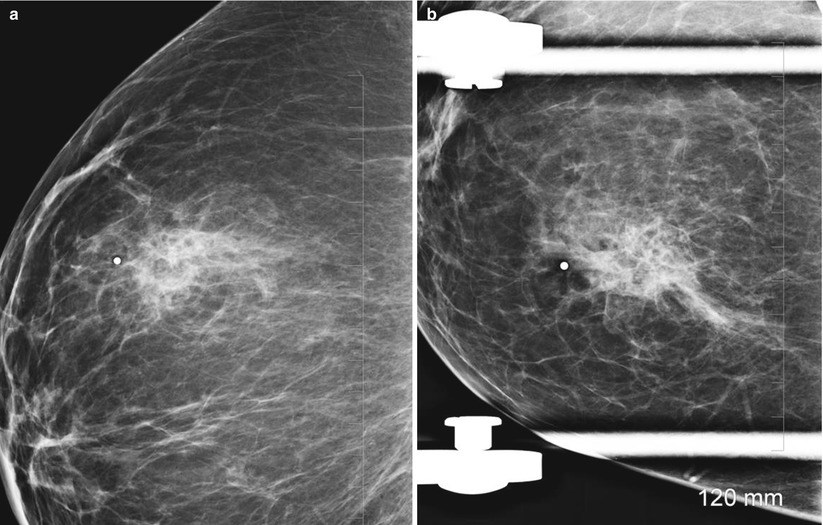

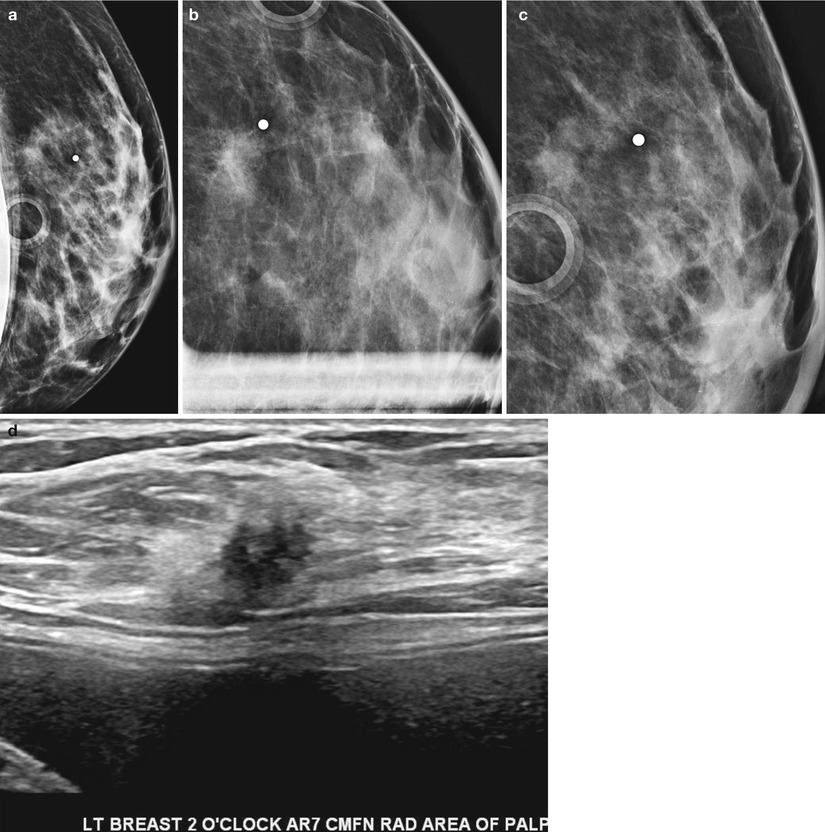

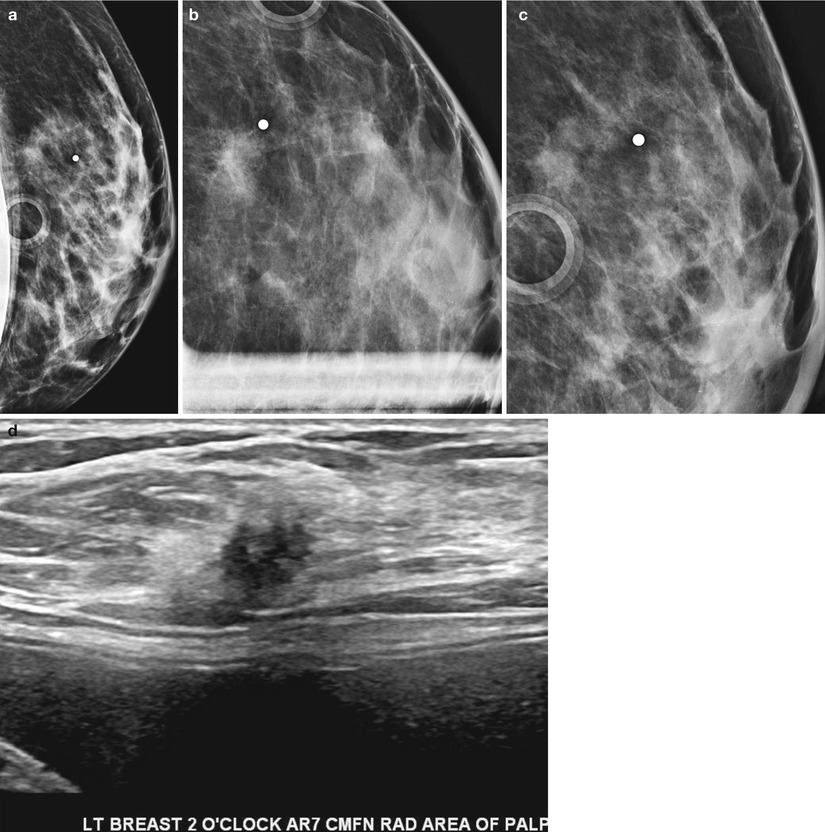

Fig. 5.11

(a–d) Small palpable invasive ductal cancer with subtle visibility on a screening mammogram. (a) Mediolateral view of left breast shows a questionable area of increased density in a breast with dense fibroglandular parenchyma. (b) Spot compression view in the craniocaudal projection reveals a small focal asymmetry. (c) Spot compression view in the mediolateral projection reveals a small focal asymmetry. (d) Ultrasound reveals a small solid mass with microlobulated borders and malignant features

In summary, most cases of asymmetry are due to a summation artifact and appropriately categorized as benign with a recommendation for routine follow-up. Those that are determined not to be a summation artifact after a diagnostic work-up and if new or enlarging or palpable following either a negative ultrasound examination or an ultrasound finding of an indeterminate mass get a category 4 assessment with a recommendation for a biopsy. Uncomplicated focal asymmetry seen on a baseline screening mammogram or when there are no prior mammograms available for comparison need to be worked up with diagnostic mammography and if persistent assessed by sonography; if there is no benign finding accounting for the focal asymmetry, the finding is considered probably benign with a recommendation for a short interval follow-up in 6 months. Uncomplicated global asymmetry does not require a diagnostic work-up and is assigned a BI-RADS 2 category with a recommendation for routine screening. Uncomplicated developing asymmetry is always recalled and if determined not to be due to summation or a sonographic benign correlate is categorized as a BI-RADS 4, with a recommendation for a biopsy. Asymmetry, global asymmetry, or a focal asymmetry associated with a palpable finding, architectural distortion, or suspicious microcalcifications is always an indication for biopsy.

One-View Density

Density that is visible on one view and defined as asymmetry is often due to summation artifact. Women are recalled for a diagnostic mammogram where supplemental views are obtained to exclude summation artifact as well as to identify a corresponding area on the orthogonal view. Two methods have been described to triangulate a lesion in two projections [38]. First is the arc method where the distance from the nipple to the density is used to form the radius of an arc with the nipple at its center. In the straight line method, the distance from the nipple to a perpendicular line passing through the density is measured. A corresponding density is sought in the orthogonal plane along the arc or the line; if none is found the finding is considered as an asymmetry. One-view asymmetry if not a summation artifact may be caused by an abnormality that is not included on the second view due to technical difficulties in including that area of the breast, such as lesions in the axillary fold, very medial in the chest, very posterior, or in the inframammary fold [38]. When a lesion is apparent only on the mediolateral oblique view, a straight mediolateral view has to be obtained to determine if the finding persists and its location in the breast. Lesions that are in the medial breast will move superiorly and those in the lateral breast will move inferiorly on the straight mediolateral views. Rolled views are obtained for lesions that are seen only in the craniocaudal view, to confirm that it is a real finding or not [39].

A new area of focal asymmetry is sometimes related to initiation of hormone replacement therapy [HRT]. In such cases repeat mammogram after cessation of HRT may demonstrate a resolution of the focal asymmetry. A developing asymmetry that may appear less prominent but persists following cessation of therapy could at least in theory represent an estrogen-sensitive breast cancer [31]. Short-term cessation of hormone replacement prior to performance of screening mammography has been suggested although patient compliance may be an issue; one study reported that a majority of women [54 %] were unwilling to stop HRT for 1–2 months prior to undergoing a screening mammogram [40]. There is no proven benefit in stopping HRT in all patients prior to screening mammography. No significant reduction in recall rate was seen in those in whom HRT was suspended for 1–2 months prior to screening mammography [41].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree