An increasing number of nonpalpable breast lesions are identified due to screening mammography and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After appropriate diagnostic imaging workup, many of these image-detected abnormalities require a biopsy for pathologic confirmation. The positive predictive value of mammography (the number of cancers diagnosed per number of biopsies recommended) historically has ranged from 15% to 35%.1 Fortunately, a substantial number of these lesions are initially evaluated with percutaneous image-guided breast biopsy, providing a less costly, less invasive method to obtain an accurate diagnosis without sacrificing accuracy. After a benign diagnosis is obtained with a minimally invasive image-guided biopsy, no further workup is recommended, and the patient is placed in an established follow-up protocol. The goal of reserving open surgical biopsy for definitive clinical management and eliminating it for the sole purpose of diagnosis is increasingly being accomplished.

Even with the advent of image-guided needle biopsy, there is still a need for localization and excision of nonpalpable (and some palpable) lesions. Despite the potential advantage of image-guided percutaneous breast biopsy, some patients are only satisfied with complete surgical removal of their mammographic abnormality. Other patients may not have access to facilities with equipment for stereotactic procedures because of their insurance plans or locale. There are also certain patient characteristics, such as obesity or arthritic conditions and certain lesion types and locations (diffuse calcifications/posterior near the chest wall) that make image-guided biopsy with stereotactic guidance difficult or inappropriate. Excision is also indicated after an image-guided percutaneous breast biopsy if the diagnosis is malignant or high risk (such as atypical lobular or ductal hyperplasia) or if there is discordance between the radiographic impression and the pathologic result.2,3 Medical judgment is crucial in any image-guided breast biopsy program. If the procedure was technically unsatisfactory, the imaging was less than ideal, or poor quality tissue cores were obtained, the physician should not hesitate to recommend a surgical excision. Moreover, because most of these abnormalities are nonpalpable, a localization procedure would be necessary, which traditionally was performed with mammography guidance but increasingly is accomplished with intraoperative ultrasound.

Advantages/Disadvantages of Mammographic versus Intraoperative Ultrasound Localization

Open surgical biopsy with preoperative wire localization has several drawbacks. The failure of removing the targeted lesion has been reported as high as 22%.4,5 The ability to accomplish a successful biopsy of a nonpalpable breast abnormality may be limited by substandard preoperative wire placement in radiology; dislodgement, migration, or transaction of the wire either pre- or intraoperatively; the failure of the surgeon to excise the lesion accurately; or the failure to obtain a specimen radiograph to confirm that the lesion was adequately removed. Finally, it may be difficult for the pathologist to identify a very small lesion accurately within a large volume of excised tissue.4-6

Patients report high anxiety with the wire placement procedure with episodes of syncope in 9% to 20% of patients who are awake and usually upright.4-6 Many patients report that the localization was the most difficult part of their perioperative experience. From the surgeon’s perspective, scheduling early morning cases is limited by the ability to schedule the localization procedure in the radiology department, and there may be delays in the surgery schedule because of complicated or difficult localizations. Dislodgement or transection of the localization wire is another disadvantage of preoperative needle-wire localization, which could lead to an increased miss rate at the time of surgical excision.4,6 In addition, the clip marker placed at the time of a successful stereotactic breast biopsy, where image evidence of the lesion has been removed, can migrate as much as 1 cm on average and as much as 2 cm up to 20% of the time.7 These difficulties have led to the use of preoperative and intraoperative ultrasound localization as a replacement for the traditional preoperative localization with mammogram guidance.8-11

Preoperative wire localization for surgical excision is usually performed with orthogonal mammography in the radiology department.6,12-14 The needle-wire combination is guided into the breast through the fenestrated compression paddle alongside or through the target lesion, parallel to the chest wall, using the approach with the shortest skin-to-lesion distance. The patient’s breast is then compressed in the corollary view, and the alphanumeric grid is used to adjust the depth of the needle-wire combination before the needle is withdrawn to engage the tip or barb of the wire.14 At this point, craniocaudad and straight mediolateral mammograms can be taken with the localization wire in place. It is helpful if the radiology technologist places “BB” skin markers on the nipple and at the point where the wire enters the skin. This allows the surgeon viewing the localization mammograms in the operating room to judge the distance the wire travels from the skin to the lesion. The key to a successful excision after an accurate wire placement is to view the craniocaudad mammogram and determine if the tip of the wire is lateral or medial to the lesion. In addition, viewing the mediolateral film determines if the lesion is above or below the wire tip. The nipple and entry site markers help determine how far above/below and medial/lateral the lesion is to the nipple, and by triangulating the depth from the entry marker, the position of the incision is chosen. The incision, therefore, does not need to extend from the wire entry site to the lesion but can be made in a cosmetic fashion on the skin more directly above the lesion.

Preoperative wire localization can also be performed with stereotactic guidance.15 Using the same stereotactic principles for a stereotactic-guided percutaneous breast biopsy, the position of the lesion can be accurately calculated using the stereotactic table software. A needle holder placed on the stereotactic table guides the wire of choice to the target lesion. With this technique, it is sometimes difficult to choose the skin entrance site to have the smallest skin-to-lesion distance. Regardless of the technique used to place a localization wire, it is helpful if it is not greater than 5 to 10 mm from the lesion to limit potential errors in excision and improve accuracy.

Schwartz et al first described the use of intraoperative ultrasound for localization and excision in 1988.16 Wilson et al, in 1998, described using ultrasound in radiology to localize the lesion by marking the skin and reporting the depth of the target for the surgeon.17 Since that time, there have been numerous reports on using intraoperative ultrasound for the successful excision of partially palpable and nonpalpable breast abnormalities along with obtaining adequate margins when excising malignant lesions.8-11,18,19

Intraoperative ultrasound is a valuable tool for the breast surgeon. Ultrasound can be used to aid in the excision of palpable and nonpalpable lesions with or without placement of a wire for localization during the procedure. For the vaguely palpable lesion, especially one that has been confirmed by a prior image-guided biopsy to be malignant, ultrasound can give the surgeon information about the size and depth of the lesion and help in decision making regarding incision placement and how much tissue to remove. The use of intraoperative ultrasound for localization can allow for earlier start times in the operating room and avoid delays in radiology. Because the surgeon can directly visualize the lesion in the position the patient will be in during removal of the lesion, incision placement is more accurate and placed appropriately close to the lesion with a greater chance for an improved cosmetic result.10,11 Intraoperative use of ultrasound is associated with a higher free margin rate, less tissue removal, and immediate confirmation of removal of the lesion.10,18

The operating surgeon can perform wire localization using ultrasound guidance immediately before surgery after the patient is placed on the operating table, eliminating a trip to radiology preoperatively. With intraoperative ultrasound wire placement for localization, the patient is supine and is either sedated or under general anesthesia, eliminating additional pain, anxiety, or syncope. The wire placement can be performed before the patient is prepped and draped. After the surgeon scrubs and the patient is prepped, the wire is placed using a sterile technique with an ultrasound transducer cover, sterile gel packets, and localization wires. When the operating surgeon places the wire personally, there is much more control over the skin entrance site and the direction of the wire. The surgeon gains information about the depth of the lesion and is better able to visualize the location of the wire tip. This allows wire placement in accordance with the location and direction of the planned incision.

With the appropriate sterile prep and/or draping, ultrasound imaging is performed to visualize the target lesion. Imaging is optimized with equipment designed for high resolution, near- field imaging, using a linear array transducer with a minimum 7.5-MHz frequency. If the wire is placed prior to the patient being prepped and the surgeon having scrubbed, the transducer does not require a sterile sleeve or cover, and the skin may be simply prepped with an alcohol wipe. When using an ultrasound transducer cover for wire placement under sterile conditions, it is important to place ultrasound gel on the inside of the sleeve to create an acoustic coupling between the transducer and the sleeve. Individual packets of sterile gel are available to use on the skin, or sterile Betadine gel may be used for acoustic coupling. If the patient is not under general anesthesia, local anesthetic can be directed under real-time visualization to eliminate the concern of obscuring the target lesion that may be experienced with mammogram guidance.

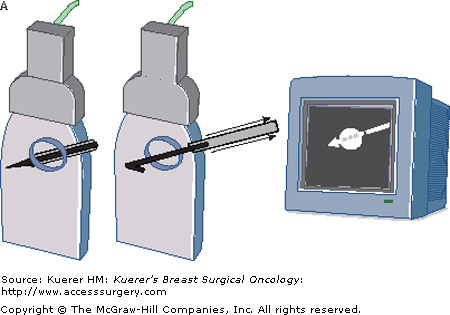

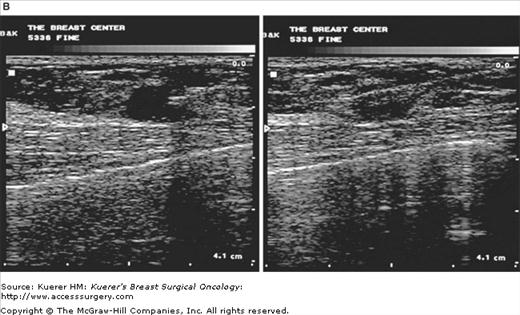

Multiple localization wires—Hawkins (Boston Scientific; Watertown, Massachusetts), Bard (CR Bard, Inc; Covington, Georgia), or Kopans (Cook; Bloomington, Indiana)—that previously were used only for mammographic localization are available and easily inserted under ultrasound guidance, and the choice is physician preference.20 The Hawkins FlexStrand wire offers the advantage of easily bringing the wire into the excision cavity without causing a cumbersome bend in the wire, and the cabling of the wire make accidental transection more difficult. The Bard wire is preferred by some for its ability to be retracted back into the placement needle after it has been engaged to allow for readjustment of location. Regardless of wire type, the needle-wire combination is inserted at the proximal edge of the ultrasound transducer. As the localization needle-wire is advanced toward the target lesion, alignment is maintained within the narrow ultrasound scan plane, which follows the long axis of the transducer. The angle of insertion is determined by triangulating between the depth of the lesion as seen on the ultrasound monitor and the length of the transducer footplate (Fig. 56-1). Once guided through the target to the distal side, the needle is withdrawn, engaging the wire hook to minimize the chance that it will become dislodged during dissection. By placing a wire with intraoperative ultrasound guidance, the insertion site is usually no more than a few centimeters (based on the length of the transducer footplate) from the center of the proposed incision site, directly over the targeted lesion. Once the incision is made, the wire can be brought into the confines of the excision cavity and its direction and depth of placement used to guide an appropriate excision.

Figure 56-1

A. The needle-wire combination is inserted at the proximal edge of the ultrasound transducer and advanced toward the target lesion, maintaining alignment within the narrow ultrasound scan plane, which follows the long axis of the transducer. Once guided through the target to the distal side, the needle is withdrawn, engaging the wire hook to minimize the chance that it will become dislodged during dissection. B. The angle of insertion is determined by triangulating between the depth of the lesion as seen on the ultrasound monitor and the length of the transducer footplate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree