Abstract

Male factor contributes up to 50% of all infertility cases, making the proper evaluation and management of male infertility a critical part of the care of the infertile couple. The evaluation of the infertile male aims to identify correctable causes of infertility that can guide therapeutic decision making for the infertile couple while also detecting significant medical problems related to infertility. The management of male infertility involves a combination of lifestyle, medical, and surgical strategies, and with the advent of advanced reproductive techniques, even the most severe male factor infertility can often be successfully overcome.

Keywords

Male infertility, semen analysis, azoospermia, oligospermia, ejaculation, vasal reconstruction, sperm retrieval, ART

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of regular, unprotected intercourse, affects 8 million couples in the United States, of which up to 50% have a male contributory factor. Overall, up to 12% of men of reproductive age worldwide suffer from male infertility. Fortunately, the past 50 years has seen a tremendous increase in our understanding of male infertility and has paved the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to help this cohort of infertile patients. In particular, the advent of advanced reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) has enabled men, for whom fatherhood could be achieved previously only through donor sperm or adoption, to now father biological offspring.

Currently, both the American Urological Association and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine advocate that the initial screening evaluation of the infertile couple include investigation of both partners in parallel. In this chapter, we will provide an up-to-date outline of evaluation and treatment algorithms that guide the management of the infertile male.

Evaluation of Male Infertility

- ◆

Initial screening evaluation of male infertility should include a thorough history, a physical examination, and two semen analyses.

- ◆

Semen analyses should be performed after 1 to 5 days of abstinence and be spaced at least 7 days apart.

- ◆

While not diagnostic of male infertility, semen analysis is a cornerstone in the evaluation of male infertility.

- ◆

Further investigations of male infertility are directed by the initial screening evaluation, which may be broken up into low semen volume, oligoasthenoteratospermia, or azoospermia.

- ◆

Endocrine evaluation of male infertility should include at least serum testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

When and On Whom to Perform an Evaluation of Male Infertility

An initial screening evaluation on both partners is recommended if a couple has not conceived a pregnancy after 12 months of regular, unprotected intercourse. Alternatively, an earlier evaluation is justified if the female partner is older than 35 years old, if either partner has a medical history or physical findings suggestive of decreased reproductive potential, or if either partner is concerned about the male’s reproductive potential. Men who do not have a partner but who are concerned about their reproductive potential should also undergo an initial screening evaluation.

The goals of the evaluation of male infertility are to identify and treat correctable causes of male infertility that could then result in natural pregnancy, to guide treatment options in those for whom natural pregnancy is unlikely to occur, and to identify significant medical problems that are associated with infertility ( Box 23.1 ).

Adult polycystic kidney

Brain tumors

Cystic fibrosis

Diabetes

Hemochromatosis

Hypopituitarism

Klinefelter syndrome

Multiple sclerosis

Pituitary adenoma

Prostate cancer

Retroperitoneal tumors

Spinal cord tumors

Testis cancer

Thyroid disease

Urinary tract infection

Initial Screening Evaluation

The initial screening evaluation of the infertile male should include a detailed history and physical examination as well as a minimum of two semen analyses.

History and Physical Examination

A thorough reproductive history ( Table 23.1 ) is a critical component of the initial screening evaluation of the infertile male and should cover coital frequency and timing, duration of infertility, prior fertility, developmental history and childhood illnesses (including hypospadias, congenital anomalies, and onset of puberty), current systemic illnesses (especially diabetes mellitus, cystic fibrosis, cancer, and infections), surgical history (with a focus on scrotal, pelvic, retroperitoneal, and inguinal surgeries), sexual history (with a history of sexually transmitted diseases), medications and allergies, and exposure to gonadotoxins (both chemical and environmental toxins, such as heat [ Table 23.2 ]). Additionally, a family history of cryptorchidism, infertility, disordered sexual differentiation, or hypogonadism, and/or a social history with frequent alcohol, tobacco, or recreational drug use may suggest potential etiologies for male infertility.

| Infertility history |

|

| Sexual history |

|

| Past medical history |

| Developmental history |

|

| Medical history |

|

| Surgical history |

|

| Family history |

|

| Medications |

| Social history |

|

| Medications |

|

| Environmental |

|

A general physical examination with an emphasis on the genitalia can also provide important information. Upon initial inspection, note should be taken of obesity, secondary sex characteristics, hair distribution, and gynecomastia. Specific examination of the genitalia should include the phallus, which should be examined for hypospadias, penile curvature, and plaques that may interfere with proper semen deposition within the vagina. Both testes should be examined for size, consistency, and the presence of masses. Eighty-five percent of testicular volume is made up of seminiferous tubules in which spermatogenesis occurs, and testicles smaller than the normal adult size of 20 mL (or 4 cm × 3 cm) may be associated with impaired spermatogenesis.

Careful attention should be paid to the presence, consistency, and nodularity of the epididymides, which may help to identify obstruction and/or infection, while palpation of both vasa deferens can diagnose vasal agenesis, atresia, or injury. More specifically, congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) is a clinical diagnosis that can be made on physical examination. Palpation of both spermatic cords in the supine and standing positions both with and without Valsalva enables the diagnosis of varicocele, which is also a clinical diagnosis. Scrotal ultrasound may be used to confirm the diagnosis of varicocele, but those subclinical varicoceles found only on ultrasound (and not on physical exam) are unlikely to be clinically relevant. Finally, a digital rectal exam may help identify dilated seminal vesicles, ejaculatory duct cysts, or utricular cysts that may contribute to obstructive etiologies of male infertility.

Semen Analysis

Along with a thorough history and physical examination, semen analysis has long been the pillar upon which male infertility is evaluated and managed. While an abnormal semen analysis (with the exception of azoospermia) cannot delineate between fertile and sterile, abnormal semen quality is associated with decreased chances of natural conception.

To account for the large degree of biological variability between semen samples, at least two semen analyses should be performed. Patients should be given specific instructions regarding the need for 2 to 5 days of abstinence prior to undergoing semen analysis with the two semen analyses preferably spaced at least 1 week apart. The semen sample can be collected either by masturbation into a specimen cup or by intercourse with the use of a special semen collection condom that does not contain any spermatotoxic agents. In particular, lubricants should be avoided. If a specimen cannot be produced at the laboratory for analysis, it should be kept at room or body temperature during transport and delivered to the laboratory for analysis within 1 hour. Further delays can affect semen and sperm parameters, such as sperm motility, which decreases dramatically after 2 hours.

Parameters examined in routine semen analysis can be broken up into macroscopic and microscopic parameters. Key macroscopic parameters include semen volume, viscosity, color, pH, and coagulation/liquefaction; key microscopic parameters include sperm count/concentration, sperm motility, and sperm morphology. After analyzing the semen analyses of 1859 new fathers from eight countries across three continents, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the normal reference ranges for most of the key parameters of semen analysis ( Table 23.3 ). To establish the reference ranges, the WHO applied a one-sided lower reference limit of the 5th percentile to the semen parameters of the 1859 new fathers. While this methodology does provide lower thresholds for semen parameters in fertile men, it fails to answer the more relevant clinical question of which specific semen parameters and cutoffs are able to delineate between male fertility and subfertility. Efforts to identify specific semen parameters that can distinguish between male fertility and subfertility have instead found that while semen parameters are associated with fecundity, neither sperm concentration, morphology, nor motility could be considered diagnostic of infertility either alone or in combination. Rather than a direct diagnostic test of male infertility, the semen analysis should instead be considered an important contributor to the overall picture of male fertility.

| Semen Analysis Parameter | Reference Value |

|---|---|

| Ejaculate volume | 1.5 mL |

| Sperm concentration | 15 million sperm/mL |

| Sperm count | 39 million sperm/ejaculate |

| Total motility | 40% |

| Total progressive motility | 32% |

| Sperm morphology | 4% normal (strict criteria) |

| Sperm viability | 58% |

| Sperm agglutination | Absent |

| White blood cells | <1 million leukocytes/mL |

Further Investigations and Complete Evaluation

Results from the initial screening evaluation of male infertility may be normal or abnormal. Men with unremarkable reproductive histories and normal semen analyses are highly unlikely to harbor male infertility, and an in-depth assessment of potential female factors should be undertaken. However, if any abnormalities are detected on the initial screening evaluation of male infertility, further investigations that constitute the complete evaluation (often driven by the specific abnormalities detected) are required.

Endocrine Evaluation

While a specific endocrine cause of impaired sperm production is identified in only 2% of men with male factor infertility, an endocrine evaluation is still indicated in men with abnormal semen analyses (especially in those with sperm concentrations less than 10 million/mL), abnormal sexual function, or findings suggestive of endocrinopathy. At minimum, an endocrine evaluation for male infertility should include serum FSH and morning testosterone levels. A low serum testosterone level (<300 ng/dL) should prompt the testing of a second morning serum testosterone level alongside serum LH and prolactin levels. The importance of obtaining a second morning serum testosterone level should not be understated since gonadotropins and testosterone are typically released in a pulsatile manner, and testosterone levels commonly demonstrate a physiologic decline over the course of the day. The characteristic hormone profiles for various etiologies of male infertility are described in Table 23.4 . In particular, while normal FSH levels (≤7.6 IU/L) do not guarantee normal spermatogenesis, elevated FSH levels often indicate an abnormality with spermatogenesis.

| Condition | Testosterone | FSH | LH | Prolactin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Primary testicular failure | ||||

| Hypospermatogenesis | Normal/Low | High | High/Normal | Normal |

| Maturation arrest | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Sertoli cell only | Low | Very high | High | Normal |

| Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism | Low | Low | Low | Normal |

| Hyperprolactinemia | Low | Normal/Low | Low | High |

| Klinefelter syndrome | Low | Very high | High | Normal |

Low Semen Volume

- ◆

Low semen volume may be attributable to ejaculatory dysfunction, hypogonadism, ejaculatory duct obstruction, or CBAVD.

- ◆

An endocrine evaluation, postejaculatory urinalysis, and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) can help identify the cause of low semen volume.

Postejaculatory Urinalysis

The presence of low semen volume (<1.0 mL) should prompt a systematic algorithm to delineate the cause ( Fig. 23.1 ). Potential etiologies for low semen volume include improper collection, CBAVD, hypogonadism, ejaculatory dysfunction, and ejaculatory duct obstruction. In men with normal serum testosterone levels and palpable vasa deferentia, a postejaculatory urinalysis should be performed to rule out retrograde ejaculation. The presence of a greater sperm count in the urine specimen pellet postejaculation following centrifugation is indicative of retrograde ejaculation.

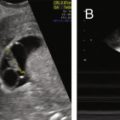

Transrectal Ultrasound

The absence of seminal fructose or a seminal pH less than 7 may suggest absence/atrophy of the seminal vesicles or ejaculatory duct obstruction. The diagnostic tool of choice for ejaculatory duct obstruction is TRUS. The presence of midline cysts, dilated seminal vesicles (anterior-posterior diameter >1.5 cm), or dilated ejaculatory ducts (>2.3 mm) on TRUS is suggestive, but not diagnostic, of complete or partial ejaculatory duct obstruction. If dilated seminal vesicles are seen on TRUS, TRUS-guided seminal vesicle aspiration may be performed to confirm the diagnosis (with simultaneous cryopreservation of any sperm found). Patients with unilateral absence of the vas deferens and low volume azoospermia may have a variant of CBAVD and should undergo genetic screening for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) before TRUS. Forty percent of men with CBAVD and a negative CFTR screen will demonstrate renal anomalies and should be additionally screened with abdominal ultrasound. On the other hand, those with CBAVD and a positive CFTR screen rarely exhibit renal anomalies and do not warrant abdominal ultrasound. Men with detectable CFTR mutations should undergo thorough genetic counseling prior to any fertility treatment.

Oligospermia/Asthenospermia/Teratospermia

- ◆

Oligoasthenoteratospermia may be caused by varicocele, genetic abnormalities, immunologic infertility, or gonadotoxic exposures.

- ◆

Genetic testing comprises primarily of karyotype and Y-microdeletion testing and is indicated in men with severe oligospermia or nonobstructive azoospermia (NOA).

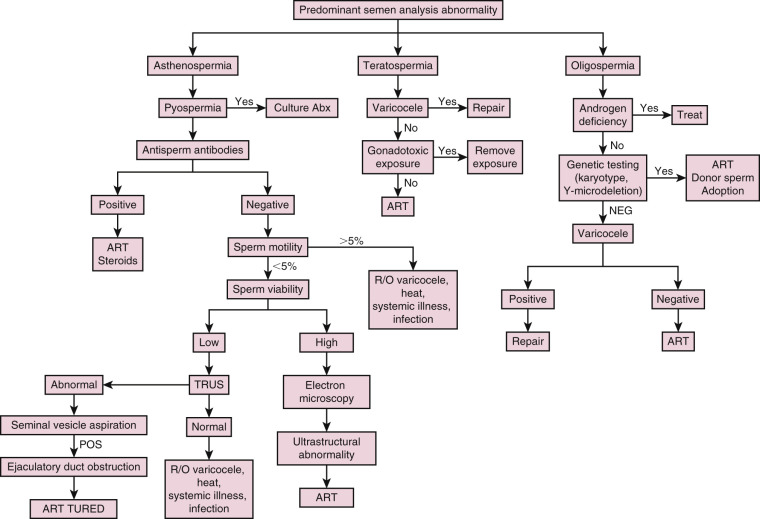

Infertile men may demonstrate abnormalities in sperm concentration (oligospermia), motility (asthenospermia), and/or morphology (teratospermia), which are often seen together. Potential causes for these abnormal semen parameters include endocrinopathies, genital tract infections, immunologic antisperm antibodies (ASA), varicoceles, and genetic abnormalities ( Fig. 23.2 ).

Semen Leukocytes

Genital tract infection or inflammation may result in the presence of leukocytes in the semen, which can negatively affect sperm motility and function via the overproduction of reactive oxygen species. Since both leukocytes and immature germ cells appear as “round cells” on microscopy, differentiating between the two types of cells can be tricky, but can be accomplished using cytologic staining or immunohistochemistry. Those with pyospermia (>1 million leukocytes/mL) should be evaluated further to rule out or treat genital tract infection or inflammation. Since 83% of semen cultures in asymptomatic infertile men with pyospermia are positive with multiple organisms, the workup should include an examination of expressed prostatic secretion for leukocytes instead, as well as a urethral culture for Chlamydia and Mycoplasma .

Antisperm Antibodies

Patients with isolated asthenospermia or sperm agglutination may be bound by ASA, which are a rare cause of male infertility that can form following a breach of the blood-testis barrier after vasectomy, trauma, torsion, biopsy, or testicular cancer. ASA, which are not routinely tested for, can be found in the serum or seminal plasma via indirect antibody agglutination assays or directly bound to the sperm via a direct immunobead test. ASA are considered significant if over 50% of sperm are bound by ASA. Since the presence of ASA correlates with spermatogenesis, the detection of serum ASA also may be clinically useful in differentiating azoospermic men with obstructive etiologies versus those with nonobstructive etiologies without the need for a diagnostic testicular biopsy. Azoospermic men with positive ASA are more likely to have an obstructive etiology.

Genetic Testing

Genetic abnormalities can cause problems with sperm production or transport, and men with severe oligospermia (sperm concentration <5 million/mL) or NOA should be worked up for genetic abnormalities ( Table 23.5 ). In addition to the previously discussed CFTR mutations, karyotypic chromosomal abnormalities and Y-microdeletions are of concern. In total, genetic abnormalities are estimated to account for 15% to 30% of male infertility, though the overwhelming majority of these abnormalities have yet to be discovered or understood.

| Genetic abnormality | Phenotype | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal abnormality | ||

| Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) |

| 1 : 500 of newborn males |

| 47,XYY |

| 1 : 1000 of newborn males |

| 46,XX male |

| 1 : 20,000 of newborn males |

| Chromosomal translocations/inversions |

| 1 : 600–1 : 1000 of newborn males |

| YCMD | 10%–15% of men with severe oligospermia or NOA | |

| AZFa |

| 2%–5% of YCMD |

| AZFb |

| 13%–16% of YCMD |

| AZFc |

| 60%–75% of YCMD |

| Combination deletions |

| 10%–14% of YCMD |

| Single gene mutations | ||

| CFTR gene mutations |

| 1 : 25 carriers, 1 : 2500 of live births |

| Kallman syndrome ( KAL1 and FGFR1 ) |

| 1 : 30,000 of live births |

| AR gene mutations |

| 1 : 60,000 of live births |

| INSL3-LGR8 |

| 4%–5% of newborn males |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree