Males infrequently develop breast cancer; hence the dearth of prospective randomized trials in male breast cancer. Our knowledge of the disease has been derived mostly from retrospectives studies. Due to the similarities of disease behavior in men and women with breast cancer, the management and treatment of male breast cancer has been guided by conclusions drawn from studies conducted in women.

Breast cancer represents less than 1% of all cancers in men1; the male to female ratio is 1:100.2 Since 1973 there has been a gradual increase in the incidence of male breast cancer, the reasons for which are unclear. Nonetheless the overall incidence remains low, at about 1 case per 100,000 population per year.3 Unlike women, where breast cancer displays a bimodal distribution, the disease in men increases exponentially with age. The median age at presentation for male breast cancer is 65 to 71, unlike with women, in whom breast cancer is seen about 5 to 10 years earlier.4 The epidemiology of breast cancer in men is similar to that in women, such that North America and Europe see the highest incidences, while Japan has the lowest.5 Interestingly, in sub-Saharan countries in Africa where infectious liver damage is common, such as in Zambia6 and Uganda,7 7% to 14% of breast cancer cases occur in men. In the United States, tumor registries indicate that male breast cancer is most common in African American men, intermediate in non-Hispanic Caucasian men and Asian-Pacific Islanders, and lowest in Hispanic men. In 2009, the American Cancer Society estimated that 1910 men will have been diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States, with 440 deaths.8

Similarly to women, hormonal factors seem to play an important role in the development of breast cancer in men. A frequently cited risk factor is Klinefelter syndrome, where an extra X chromosome is inherited in these male patients. The risk of developing breast cancer in patients with Klinefelter syndrome is increased by 58-fold, with an absolute risk of 3%.9 Patients with this syndrome have atrophic testes with high levels of gonadotropins, low levels of testosterone, and normal to low levels of estrogen, leading to a high estrogen to testosterone ratio. Also suggestive that hormonal factors may play a role, male breast cancer is seen in hermaphrodites, men having undergone feminizing surgery, and men who have received exogenous estrogen for prostate cancer, where cases of bilateral breast cancer have been described.10,11 As Klinefelter syndrome and male breast cancer are both rare diseases, it is very unlikely that a health care provider will encounter this situation; however, a breast lesion in a patient with Klinefelter syndrome must be considered suspiciously. It has been reported that 4% of men with breast cancer have Klinefelter syndrome.12

It has been suggested that male breast cancer and gynecomastia represent different ends of the same spectrum, or that gynecomastia may be a premalignant lesion. This assumption was based on the observation that men with breast cancer have the clinical and histologic diagnosis of gynecomastia in 4% to 23% and 26.5% to 88%, respectively.13 In autopsy studies of men dying from other causes than breast cancer, gynecomastia was found in 40% to 55% cases.14 Currently there is no conclusive evidence to support a causal relationship between male breast cancer and gynecomastia; it is possible, however, that both are the result of a hormonal imbalance.

Other risk factors cited in the literature include liver disorders (cirrhosis and bilharziasis), testicular injury, orchitis, history of head injury with resulting hyperprolactinemia, and prostate cancer.15 Male breast cancer has been seen more frequently in boys being treated with chest irradiation for lymphoma as well as in men exposed to nuclear fallout, such as Japanese men following World War II. Additionally, it has been proposed that electromagnetic fields and the exposure of the testis to heat may be occupational hazards.16

As in women, a family history of breast cancer is a risk factor in men. A history of breast cancer in a mother or sister confers respectively a 2.33 or 2.23 relative risk of developing breast cancer in men.17 This risk increases if the affected first-degree female relative developed breast cancer before the age of 45 years. Furthermore, 30% of men with breast cancer have a history of one or more affected first-degree relatives. Genetic predisposition to the development of male breast cancer has also been identified.18 Men who carry the BRCA1, and particularly the BRCA2, gene mutations may not only transmit them to their offspring, but are also at increased risk of developing breast cancer themselves.19 Men with the BRCA2 mutation have a 100-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer, with a lifetime risk of approximately 7% by age 80. BRCA2 is thought to represent about 15% of breast cancer in men. Men with the BRCA1 mutation are at increased risk but to a lesser degree, with a 1.2% risk by age 70.20 Men of Ashkenazi Jewish descent have a higher prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2, and therefore an increased risk of developing male breast cancer.21 Currently there are no established screening guidelines for men with higher risk of breast cancer.22

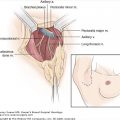

The most common presentation of male breast cancer (75%-95%) is a palpable mass. The lump is discovered by the patient in 60% of these cases.23,24 On physical exam the breast mass is painless, eccentric, and ill-defined. In as many as 80% of cases, the mass may be associated with nipple discharge. On the other hand, serosanguinous nipple discharge in a male patient is associated with breast cancer in 75% of cases. Due to the smaller size of the male breast, involvement of the skin and nipple–areola complex or the underlying chest wall is more frequently seen in men than in women. Skin fixation and ulceration is seen in 44% and 13% of cases, respectively.25

The most frequent breast complaints for which men seek medical advice are breast enlargement, a palpable mass, or breast pain.26 History and physical exam are very helpful in differentiating benign from malignant disease. Age is important, as men younger than 40 years rarely develop breast cancer. The most common diagnosis of men, even the older patients, presenting with a palpable mass remains gynecomastia.27 In a review of more than 800 male breast biopsies, 96% were benign, gynecomastia being the most common (91%) entity.28 In this series, other benign findings included lipoma, fibrosis, inflammatory changes, and normal breast tissue. Medications such as cimetidine, antipsychotics, and antihypertensives, as well as recreational drugs such as anabolic steroids and marijuana, have been implicated as causes for gynecomastia.29

Clinically, patients with gynecomastia are often seen to have diffusely enlarged and frequently tender breasts bilaterally, rather than a carcinoma, which is usually a hard palpable mass involving one breast. Nipple discharge is not a physiologic condition in men; it is most likely associated with malignancy, and requires further workup. Masses associated with skin ulceration or fixation are highly suspicious and necessitate a biopsy. The differential diagnosis of breast enlargement may also include pseudogynecomastia, which is breast enlargement due to adiposity. While no clinical finding is pathognomic of cancer or gynecomastia, those listed in Table 21-1 may be helpful in rendering a diagnosis.

| Feature | Gynecomastia | Carcinoma |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Young | Old |

| Mass | Diffuse | Localized |

| Mobile | Fixed | |

| Rubbery/smooth | Hard | |

| Centered nipple–areola | Frequently eccentric | |

| Pain | Occasionally | Uncommon |

| Skin fixation | Rare | Frequent |

| Ulceration | None | Frequent |

| Nipple discharge | Infrequent | Common |

| Nipple deformity | None | Common |

| Bilateral | Common | Rare |

| Skin | Normal | Thickened, red, or ulcerated |

| Axilla | Normal | Axillary adenopathy |

Mammography is a useful tool in the diagnosis of male breast cancer. The mammographic findings seen in breast cancer, in order of frequency, are mass, architectural distortion, or microcalcifications.27 False-negative mammography is seen more commonly in men than in women (10%-20%).30 Sonography is recommended as an adjunct to mammography, in order to further define a breast mass or to examine the breast in the case of a negative mammogram. Solid and complex cystic masses are suspicious findings at sonography.16 Sonography may also be used to assess the axillary lymph nodes. Sonography and mammography are both useful in differentiating cancer from gynecomastia. Unlike women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer, the use of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the male patient remains to be defined. The extent of systemic disease may be ascertained as clinically appropriate, by using laboratory evaluation, chest radiography, bone scan, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, or positron emission tomographic/computed tomographic (PET/CT) scan.

Pathologic evaluation of a breast mass in men can be easily performed with fine- needle aspiration (FNA) or core needle biopsy (CNBx).31 FNA is a cytologic test performed with a 10-mL syringe and a 22-gauge needle. It is important to note that the reliability of an FNA depends on the experience of the institution and the cytopathologist. CNBx is a histologic test and is performed percutaneously through a 2-mm skin incision, requiring a dedicated device. We prefer a 14-gauge needle and retrieve 5 or 6 cores of tissue. We also prefer to perform CNBx to FNA, as the former renders more tissue, which allows the differentiation between invasive and in situ cancer, as well as the estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR), in addition to HER-2/neu oncogene status. This subsequently allows for definitive surgery to be planned. The incidence of a false-negative result with either FNA or CNBx ranges from to 3% to 10%.31 The rate of an equivocal, atypical, or inadequate specimen, however, depends on the experience of the person performing the needle biopsy and/or the pathologist.

While the gold standard of managing a palpable male breast mass is excisional biopsy, the similarities to women have seen the application of the triple test (clinical exam, imaging evaluation, and pathologic assessment) to men. Should all 3 tests be consistent with a benign process, and the pathologic results are concordant with the imaging features, the patient may be observed and an excisional biopsy avoided. Furthermore, if pathologic evaluation reveals a malignant process, definitive surgery can be planned.

Men in whom breast cancer is diagnosed may develop clinically significant anxiety or depression. There are no psychosocial studies in this regard, but there is evidence that men, like women diagnosed with breast cancer, may benefit from psychosocial interventions.32 Unfortunately, there is little sex-specific information or support for the male patient.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree