Fig. 49.1

(a, b) Extratruncular and truncular LM (a) depicts a typical “extratruncular” lymphatic malformation (LM) lesion presenting as a localized swelling along the right neck extended to the submandibular region (left panel). Such lesion generally presents as a soft boggy mass along the soft tissue plane, but it could be the tip of a quite extensive lesion beneath it infiltrating to deeper tissue/structure, often seen in the head and neck region. (b) shows a common clinical condition of “truncular” LM as primary lymphedema (right panel), affecting the right lower extremity of a young male patient. It manifests as a diffuse swelling along the entire area affected by lymphatic obstruction/stasis often due to the hypoplasia of the lymph-transporting vessel

Such primitive vascular tissue from the “early” stage of embryogenesis maintains its unique mesenchymal cell characteristics originated from (lymph)angioblast. They have such evolutional potential so that they will never disappear (cf. hemangioma) but continue to grow when stimulated (e.g., female hormone, menarche, pregnancy, trauma, surgery) through the rest of life [1–3].

On the contrary, the truncular lesion is the outcome of defective development along the “later” stage of lymphangiogenesis, while the lymphatic vessel trunk is formed so that it no longer possesses the mesenchymal cell characteristics to grow/progress. But it is directly involved to the lymph-transporting system – vessels and/or nodes – resulting in various defective conditions as aplasia, hypoplasia, and hyperplasia so that the impact to the lymphatic function is more serious, clinically known as a primary lymphedema [16–18] (Fig. 49.1b).

Infrequently, both extratruncular and truncular lesions may exist together; therefore, a clear understanding on this distinctive difference between two different groups (extratruncular versus truncular lesions) from different stages of lymphangiogenesis is mandated for safe management of extratruncular LM lesions [5, 7, 9] (Fig. 49.2).

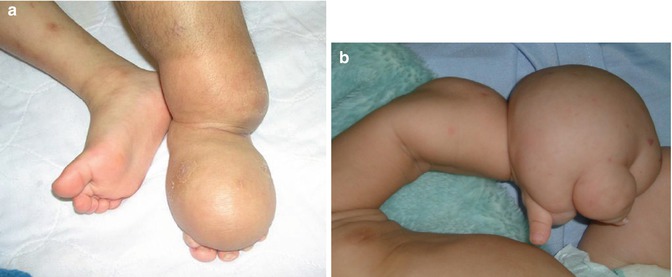

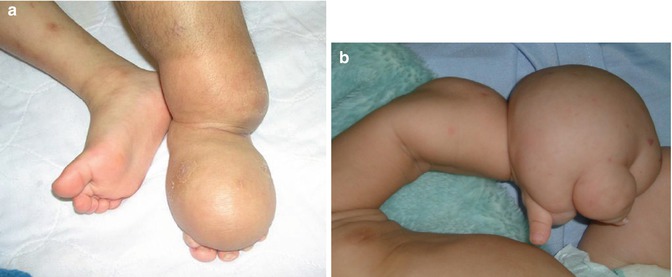

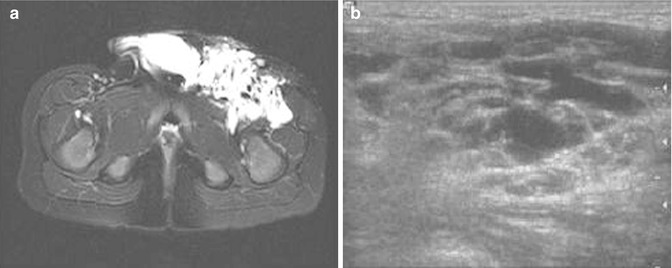

Fig. 49.2

(a, b) Mixed condition of truncular and extratruncular LM lesions (a, b), both show massive swelling of the foot (a) or hand (b) caused by combined condition of truncular and extratruncular LM lesions. A proper combination of various noninvasive and occasionally invasive tests such as direct puncture percutaneous lymphangiography is sufficient for the diagnosis, but if there is any doubt of its status, a tissue biopsy is recommended before the treatment decision is taken

General Principles and Guidelines

The vast majority of extratruncular LMs occur as independent lesions, known as a lymphangioma. Therefore, the treatment decision should follow a complete and appropriate assessment of recurrence risk involved in these unique embryological/mesenchymal cell characteristics, because “recurrence” often follows unnecessary stimulation by ill-planned treatment, especially with incomplete excision [1–3, 19].

But, by the nature/pathophysiology of the CVM development, both extratruncular and truncular LM lesions may further develop together with other CVMs. They could exist with venous malformations (VMs) [20–22] and/or arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) [23–25] further complicating the clinical picture.

These complex lesions are separately classified as hemolymphatic malformations (HLMs) and are also known as vascular malformation components of the Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome [26–28] and Parkes Weber syndrome [29–31]. Knowledge and thorough understanding of these mixed CVMs is required for proper diagnosis and appropriate management of the LM itself (Figs. 49.3 and 49.4).

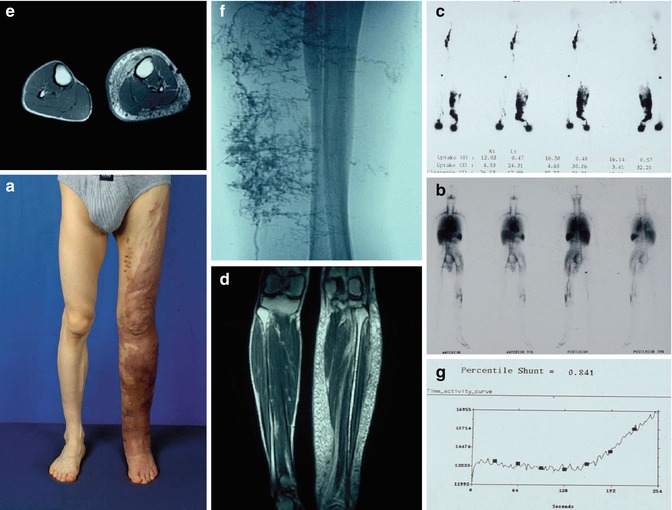

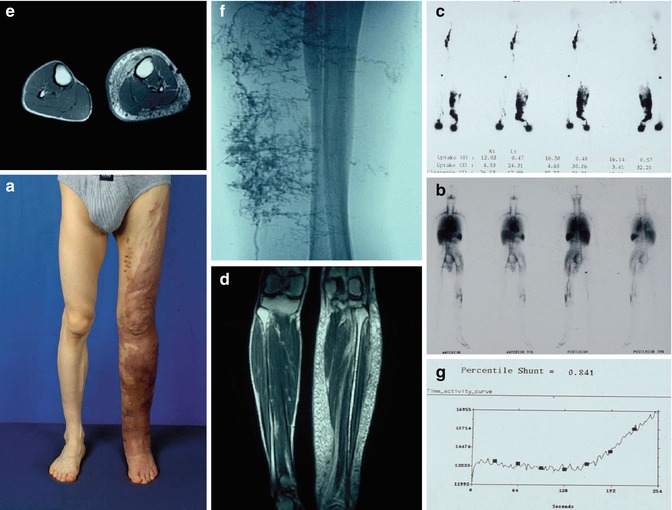

Fig. 49.3

(a–f) A complex form of lymphatic/vascular malformation. (a) illustrates a clinical condition of the swollen left lower extremity by a complex form of vascular malformation that consisted of venous, lymphatic, and capillary malformations. They altogether represent the vascular malformation component of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS). Due to the complex nature of vascular malformations, its proper management warrants precise information on each malformation involved, as well as its severity. Generally, noninvasive studies can provide basic information for the diagnosis without difficulty. (b) represents whole-body blood pool scintigraphy (WBBPS) showing the exact location and severity of coexisting venous malformation (VM) lesions as an abnormal blood pool throughout the whole body in addition to the left lower extremity itself. (c) displays radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy to identify the accurate condition/severity of lymphatic dysfunction caused by a truncular LM lesion so that lymphedema management can be initiated based on this finding. (d) and (e) represent MRI study which is essential to assess VM and LM together: a honeycomb-type image of the soft tissue is the hallmark of chronic lymphedema to confirm clinically observed diffuse swelling of the limb as primary lymphedema. (f) demonstrates typical percutaneous direct puncture lymphangiography findings of extratruncular LM lesions showing ‘lace pattern’ structure as its hall mark. (g) displays transarterial lung perfusion scintigraphy (TLPS) findings performed to rule out any

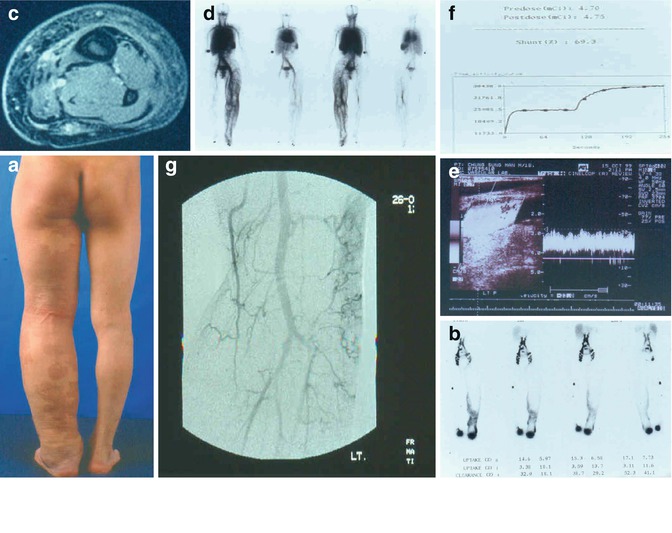

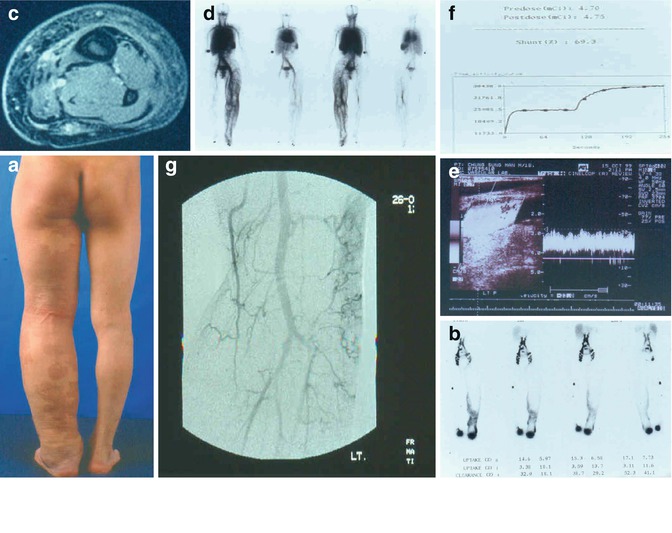

Fig. 49.4

(a–g) (a) depicts the clinical feature of Parkes Weber syndrome (PWS) affecting the left lower extremity, which looks similar to common KTS as shown in Fig. 49.3. But PWS has the AVM as an additional vascular malformation component to LM, VM, and CM. Initial evaluation with radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy (b) and MRI (c) confirmed a truncular LM lesion as the cause of primary lymphedema, while WBBPS (d) confirmed the VM component. However, duplex ultrasonography (e) shows the evidence of AVM to cause hyperdynamic arterial condition; AVM lesion (f) was further assessed to 69.3 % shunting status by the TLPS. Finally, arteriography (g) confirmed superficially located multiple micro-shunting AVM lesions scattered through the lower extremity (From Lee et al. [51])

Nevertheless, compared to other CVMs (e.g., VM and AVM), LMs are rarely life- or limb-threatening and take relatively benign course. They generally remain as the source of compression to the surrounding structure if not as the source of lymphatic leakage and subsequent infection. Therefore, not all the (extratruncular) LM lesions are mandated for aggressive care (cf. AVM) and its limited cases are indicated for the treatment.

Further, the treatment modalities associated with high morbidity (e.g., absolute ethanol sclerotherapy) [32–34] should only be considered after lower morbidity treatments have failed. Therapy often begins with safer and less risky treatment methods, such as OK-432 [35–37]. Although these methods carry less risk and morbidity, they are also associated with a higher risk of lesion recurrence. On the other hand, the treatments associated with higher morbidity, such as ethanol, carry a lower risk of lesion recurrence.

LM treatment with sclerotherapy and/or surgical (excisional) therapy should be given to lesions located near vital organs and anatomic structures that threaten vital functions with priority, e.g., respiration, vision, hearing, or eating (Fig. 49.5). Early treatment should also be considered for lesions with accompanying complications, such as lymph leakage, bleeding (LM lesions with a mixed venous component), or recurrent infections or cellulitis (Fig. 49.6). Symptomatic lesions, with or without cosmetically severe deformities or functional disability, such as of the hand, foot, wrist, and ankle, should also be considered for early therapy [38–40].

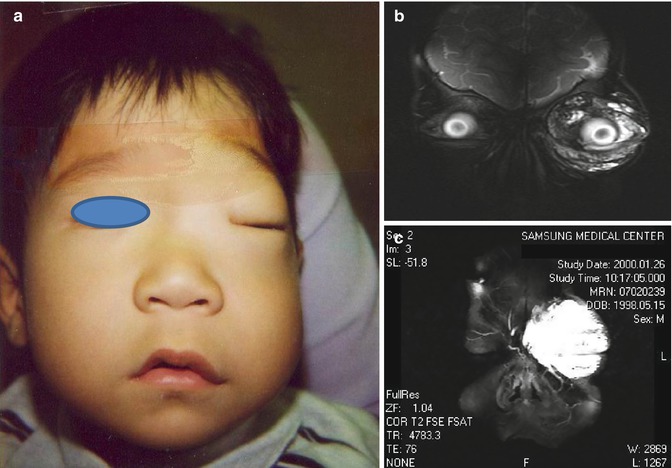

Fig. 49.5

(a–c) (a) shows a massive swelling of the left eye which was previously known as the condition of moderately puffy eyelids with mild periorbital swelling due to the infiltrating extratruncular LM, as shown in MRI findings (b, c). Such sudden complete blockage of the vision following mild infection to this LM lesion is as dangerous, if not more, than the VM or AVM lesion in terms of acute/urgent necessity of the immediate treatment which is particularly true to an infant before vision is fully matured

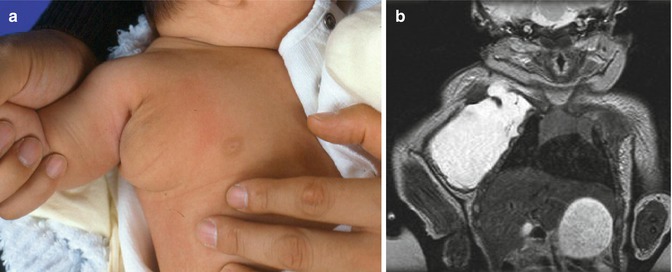

Fig. 49.6

(a–c) is the worst combination for the of LM lesions. (a) reveals the clinical outcome of chronic infection combined with lymph leakage along the scrotum. The LM lesion itself is relatively benign although it extends into the retropelvic structure as a mixed cystic type, but the infection combined with the lymphatic leakage as its complication remains a poor prognosis as a potentially life-threatening condition which may progress to general sepsis. (b) presents a difficult condition with recurrent ruptures of lymph vesicles on the hand/fingers which is already compromised with lymphedema, allowing the progression of acute skin infection. (c) shows the leakage of lymphatic fluid from the posterior thigh due to the chylo-reflux from truncular LM lesion; it is further complicated with chylo-ascites by intra-abdominal LM. This patient also has extratruncular LM lesions along the left lower extremity in addition to truncular LM lesion. These complications as well as morbidities indicate early aggressive care with priority

Definitive treatment in children should be delayed until the child reaches an age at which the risk of therapy is reduced. Unless the lesion is located at a life- or limb-threatening region and requires immediate and/or urgent treatment, conservative management, such as compression therapy, should be continued. Conservative management is usually continued in the young pediatric age group until the age of two or older, when the child can better tolerate the treatment.

Emergency lifesaving measures may be required, especially in neonatal and young pediatric patients where LM lesions cause acute respiratory or alimentary problems (Fig. 49.7).

Fig. 49.7

This massive extratruncular LM lesion affecting the entire neck became the source of an acute infection resulting in acute airway obstruction; it required a limited debulking operation to relieve the airway obstruction as an emergency lifesaving procedure. The child subsequently underwent a more radical operation to remove an expanding residual lesion along the left side of the neck

Treatment Modalities

The treatment strategy for extratruncular LM lesions has changed substantially based on observations regarding their embryology. Incomplete excision is followed by inevitable recurrence, such as cystic hygroma, and often becomes a potential source of significant complications and morbidity. Traditional surgical excision has its role in the treatment of (extratruncular) LM along with a multidisciplinary approach combined with endovascular therapy [19, 41, 42].

Surgical excision is no longer considered as a first-line therapy or as a sole treatment modality because LMs rarely become life-threatening. The combination of conventional surgical excision and endovascular therapy based on sclerotherapy should be considered initially. Endovascular therapy with either OK-432 or ethanol is usually the first treatment option. This is especially true in difficult lesions that are surgically inaccessible [35–37].

OK-432 Sclerotherapy

OK-432 is the preferred initial treatment for LM lesions. OK-432 is a lymphatic sclerosing agent. OK-432 is the lyophilized exotoxin of the low-virulence Su strain of type III group A Streptococcus pyogenes and also known as Picibanil. It is produced after removing streptolysin S-producing activity and has a specific affinity for lymphatic endothelium resulting in selective injury via a relatively benign inflammatory process [35–37].

OK-432 can easily be injected into a macrocystic lesion or cavity. Outcomes are excellent, with minimal morbidity in the majority of cases (Fig. 49.8) [35–37]. Microcystic cavernous lesions, on the other hand, are virtually impossible to treat/inject so that its efficacy is quite limited with comparatively poor outcomes. In addition, these honeycombed lesions are more likely to communicate with the lymph-transporting system, posing the additional risk of injury to the lymphatic system and perilymphatic tissues (e.g., nerves and blood vessels). Therefore, selective use with precaution is warranted although OK-432 is relatively safe compared to other sclerosing agents even when extravasation occurs.

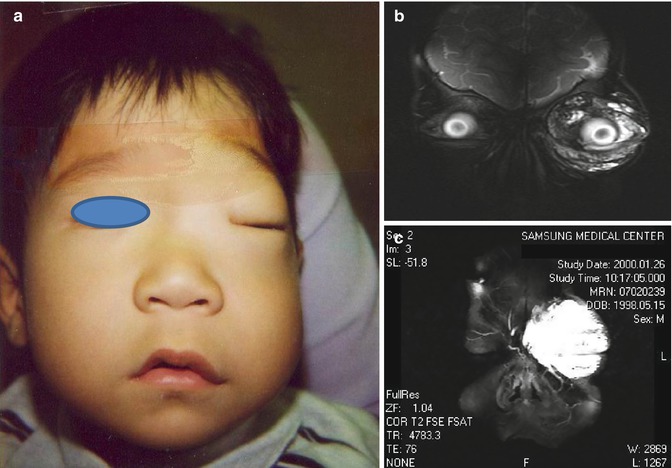

Fig. 49.8

(a, b) Indications for sclerotherapy with OK-432. (a) presents a young baby born with a relatively small soft mass lesion near the right armpit. But, lately it grew suddenly in size as shown. MRI (b) study showed a large cystic lesion extending to the root of the right side of the neck with the proximity to the brachial plexus. Therefore, OK-432 was used as scleroagent to control the lesion very effectively since it was a “macrocystic” lesion with minimal septa

Multicystic, lobulated lesions are also good candidates for OK-432 therapy. The risk of complication by the extravasation is relatively lower, especially in a mixed lesion with a microcystic component (Fig. 49.9). These lesions, however, require multiple treatment sessions in order to reduce significant local and systemic reactions.

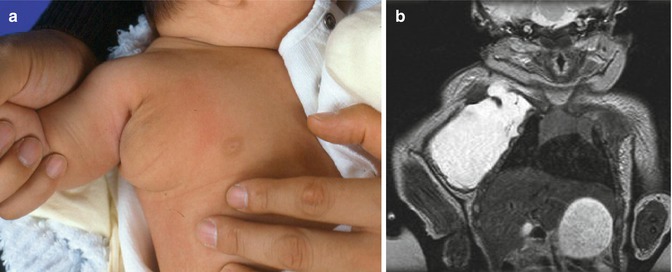

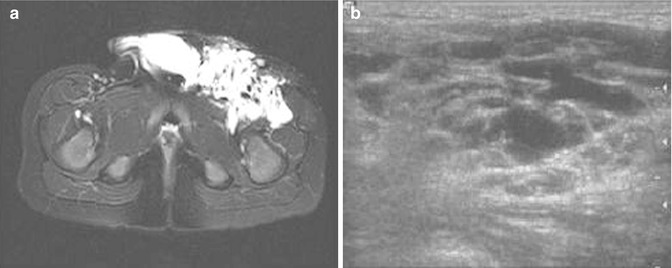

Fig. 49.9

(a, b) Microcystic LM lesions. (a) depicts extensive multicystic lesions affecting the left groin extended into the retroperitoneal space, mostly consisting of “microcystic” LM lesions. This condition was further confirmed with duplex ultrasonography (b). It became the constant source of local cellulitis. In view of the extensive nature of the lesions with proximity to the iliac-femoral neurovascular structures, OK-432 was selected to minimize the potential risk involved in multiple session therapy. However, if the recurrent/residual lesion should become a major problem in the future, a combined approach will be considered with surgical excision limited to the critically located lesion and supplemental ethanol sclerotherapy to other safer parts of the lesion when the child is grown old enough to tolerate such difficult therapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree