Locoregional spread of melanoma to its draining lymph node basin is the strongest negative prognostic factor for patients. Exclusive of clinical trials, patients with sentinel lymph node–positive (microscopic) or clinically palpable (macroscopic) nodal disease should undergo lymphadenectomy. This article reviews the management and technical aspects of surgical care for regional metastases. Adjunct therapies (immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and radiation) may supplement lymphadenectomy in certain patient populations. Surgical morbidity after lymphadenectomy can be substantial, creating opportunities for improvement via minimally invasive techniques or refined patient selection.

Key points

- •

Stage III melanoma necessitates surgical intervention via complete dissection of the affected lymph node basin.

- •

Patients with stage III disease can be divided into 2 categories: those with microscopic disease and those with macroscopic disease.

- •

The surgical approach to lymphadenectomy for sentinel lymph node–positive (microscopic) or clinically palpable (macroscopic) nodal disease varies depending on the site.

- •

Videoscopic inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy offers a new approach to traditional groin dissection with an improved morbidity profile and maintains acceptable short-term oncologic outcomes.

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma continues to present a considerable health problem in the United States. According to data collected by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 76,000 people in the United States were estimated to develop melanoma of the skin and more than 9000 people were expected to die from melanoma in 2014. However, the incidence of this disease continues to increase rapidly for both genders. Although research is underway to improve systemic therapies and several new treatment options have been approved for use, the prognosis for metastatic disease remains poor, with a 5-year survival of less than 20%.

Nodal status is the strongest single prognostic factor in patients with melanoma. The mainstay of treatment of node-positive (stage III) disease is surgical intervention via complete dissection of the affected lymph node basin. In the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), patients with occult disease are detected early, and there is evidence that shows a benefit to immediate completion lymphadenectomy with improved disease-free and melanoma-specific survival. Despite these data, a recent assessment of the quality of cancer care in the United States indicates that close to 50% of patients with positive nodes do not undergo appropriate surgical intervention, likely secondary to concerns about potential morbidity of lymphadenectomy. With the incidence of melanoma continuing to increase, new systemic therapeutic options, and improved diagnostic and staging techniques, a complete understanding of the surgical approach to stage III melanoma is paramount.

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma continues to present a considerable health problem in the United States. According to data collected by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 76,000 people in the United States were estimated to develop melanoma of the skin and more than 9000 people were expected to die from melanoma in 2014. However, the incidence of this disease continues to increase rapidly for both genders. Although research is underway to improve systemic therapies and several new treatment options have been approved for use, the prognosis for metastatic disease remains poor, with a 5-year survival of less than 20%.

Nodal status is the strongest single prognostic factor in patients with melanoma. The mainstay of treatment of node-positive (stage III) disease is surgical intervention via complete dissection of the affected lymph node basin. In the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), patients with occult disease are detected early, and there is evidence that shows a benefit to immediate completion lymphadenectomy with improved disease-free and melanoma-specific survival. Despite these data, a recent assessment of the quality of cancer care in the United States indicates that close to 50% of patients with positive nodes do not undergo appropriate surgical intervention, likely secondary to concerns about potential morbidity of lymphadenectomy. With the incidence of melanoma continuing to increase, new systemic therapeutic options, and improved diagnostic and staging techniques, a complete understanding of the surgical approach to stage III melanoma is paramount.

Patient evaluation overview

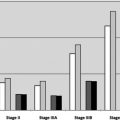

Stage III melanoma is locoregional disease. It is characterized by nodal disease, local recurrence, or in-transit disease. This article focuses solely on nodal disease. In assessing treatment strategies, patients with stage III disease can be divided into 2 categories: those with microscopic disease and those with macroscopic disease.

Microscopic Disease

Indications and approach to SLNB are covered in detail elsewhere in this issue. Data have shown that 16% to 20% of patients with a positive SLNB harbor additional positive lymph nodes and are at greater risk for disseminated disease. Current practice is to perform completion lymph node dissection (CLND) in patients with a positive SLNB; this practice is supported by the MSLT-1 trial that showed improved 10-year disease-free survival rates in patients undergoing immediate versus delayed lymphadenectomy.

Patients with microscopic disease do not warrant preoperative imaging unless symptomatic because routine radiographic staging rarely yields significant information. In addition, in the setting of microscopic disease, anatomic considerations are almost uniformly negligible, and therefore imaging to assess resectability in this patient population is not indicated. As these patients have likely been evaluated for general anesthesia previously, they do not require additional preoperative testing.

Macroscopic Disease

Individuals with palpable nodal disease carry a significantly worse prognosis than those with microscopic disease. Confirmation of metastatic disease in patients with clinical or radiographically identified lymphadenopathy should be obtained with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA). FNA is preferred rather than excisional biopsy for histologic confirmation of disease before surgical intervention, although there is conflicting evidence regarding regional control with lymphadenectomy after FNA in contrast with excision. In patients with macroscopic disease, staging evaluation (computed tomography [CT], PET/CT, MRI) is advocated before intervening surgically in order to identify those people who might harbor occult metastatic disease and in whom surgical control of regional disease has only a limited role.

Preoperative considerations for patients intended to undergo completion lymphadenectomy include physiologic and anatomic concerns. As with all procedures, ability to tolerate general anesthesia remains paramount. Although some experts consider performing lymphadenectomies under sedation or regional anesthesia, the authors of this article do not find that a feasible approach and exclusively use general anesthesia. In addition, it is very unusual for lymphatic metastases without prior treatment to be inseparable from major neurovascular structures. Given this, it is rare that volume of disease proves prohibitive to surgical resection. Nonetheless, extent of disease and proximity to or involvement of neurovascular structures should be considered on preoperative evaluation.

In the absence of a clinical trial for neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and with histologic confirmation and no evidence of distant metastases, surgical intervention is recommended. The specific procedure performed depends on the site and extent of disease, which is detailed in later sections.

Nonsurgical treatment options

The following means of therapy (neoadjuvant/adjuvant, radiation, and so forth) are discussed in detail elsewhere in this issue. This article limits the discussion of these modalities to their context in the setting of surgical lymphadenectomy.

Pharmacologic Treatment Options: Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy

Patients at high risk of recurrence following surgical treatment are candidates for adjuvant therapy. Both high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI) and pegylated interferon, characterized by a longer half-life, are approved for the adjuvant treatment of patients at high risk for relapse. Randomized controlled trials have identified bulky lymph node disease as well as ulceration of the primary tumor as independent predictors for benefit from adjuvant interferon. HDI and pegylated interferon alfa-2b are associated with improved relapse-free survival in patients with stage II and III melanoma compared with low-dose interferon or observation alone. Despite statistical significance, many specialists are still hesitant to use interferon, particularly in older patients, because the response rate is modest and side effects are significant.

The use of neoadjuvant therapy is gaining popularity as understanding of tumor biology improves. One study used HDI in patients with bulky lymphadenopathy (stage IIIb–c) to enhance surgical resectability and minimize risk of relapse. Advances in immunomodulation and targeted therapies have improved systemic treatment of disseminated disease and are being studied in both the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings. Monoclonal antibodies targeting extracellular T-cell receptors programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) as well as those targeting intracellular pathways such as BRAF inhibitors and mitogen activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitors have gained much attention given their success in the treatment of advanced metastatic disease.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment Options: Radiation Therapy

Recent data published from randomized clinical trials indicate a role for adjuvant radiotherapy in the treatment of melanoma. Patients with bulky lymphadenopathy and features correlating with high risk of recurrence are most likely to benefit. Although several studies report reduction in lymph node field relapse in patients receiving radiation therapy after complete lymphadenectomy, there is no clear survival benefit. Additional information regarding the long-term morbidities associated with radiotherapy and quality-of-life outcomes is being collected; however, given these uncertainties, many clinicians are still cautious regarding its use.

Combination Therapies

With the introduction of new immunotherapies targeting specific cell receptors and intracellular pathways, optimizing combinations of these medications could lead to major improvements in medical management. For example, ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA4 antibody, has recently been combined with pembrolizumab, an anti-PD1 antibody, with tumor regression rates greater than 80% in most responders. As the treatments for disseminated disease evolve, their use can be studied in both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, maximizing surgical control.

Surgical treatment options and technique

Surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment of patients with positive lymph nodes, whether detected by SLNB, imaging, or clinical examination. For patients with regional disease identified via SLNB, completion lymphadenectomy of the involved basin is performed. Patients with clinically palpable nodes also undergo lymphadenectomy, alternatively termed therapeutic lymphadenectomy.

Note that, in the setting of microscopic disease, lymph node basins should be managed based on the sentinel node status of that particular basin. Involved regional basins amenable to surgical intervention include cervical, axillary, inguinal, pelvic (iliac), and less commonly the epitrochlear or popliteal nodal basins, which is particularly important in patients with drainage to multiple basins or in those with unusual drainage patterns. Occasionally, lymphoscintigraphy identifies an aberrant or interval lymph node basin outside the typical regions listed earlier. Although the management of these lymph nodes is discussed later, appropriate biopsy is imperative at the time of the initial SLNB.

Cervical Lymphadenectomy

Cervical lymph node basins can harbor metastases from the head and neck, the upper trunk, and occasionally from an unknown primary site. In general, a modified neck dissection including levels II, III, IV, and V (sparing the spinal accessory nerve, the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), and the internal jugular vein) is the procedure of choice in patients with positive lymph node basins in this region. Patients with drainage through the parotid gland, with nodes identified in the parotid, and those with tumors on the frontal scalp and temporal areas should undergo concurrent superficial parotidectomy. According to validated melanoma quality indicators, a patient undergoing cervical lymphadenectomy with involvement of 4 or more levels should have at least 20 nodes resected and evaluated. Radical neck dissections are reserved for patients showing direct tumor extension to one of these structures. In patients with microscopic disease, there may be a role for selective neck dissection (involving even fewer anatomic regions), although evidence supporting this remains lacking.

Incisions for neck dissection can be oriented in a variety of ways. For a posterolateral dissection, an L-shaped incision allows better visualization of the 11th cranial nerve and level V lymph nodes. The incision runs along the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid and curves laterally along the clavicle, thus forming an L shape; when needed, an anterior extension may be performed to create an inverted T ( Fig. 1 ). The procedure can be simplified into the following steps:

- •

The external jugular vein is identified and divided near the upper limits of dissection, along the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- •

The external jugular vein and all associated lymph nodes and fatty tissue are dissected free in a cephalad to caudad manner.

- •

The sternocleidomastoid is then elevated and fatty and lymphatic tissue is dissected off the internal jugular vein, also moving cephalad to caudad.

- •

At the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid, the omohyoid is divided as it crosses the jugular vein.

- •

Dissection is carried to the base of the neck and the surgical specimen is carefully separated from the posterior aspect of the clavicle.

- •

The external jugular vein is divided inferiorly and the omohyoid divided laterally, and the operative specimen is removed en bloc.

- •

For deep dissection, the deep cervical fascia is identified. Fatty and lymphatic tissue just above this fascia is removed, moving in a caudad to cephalad direction.

- •

Cranial nerve XI is skeletonized to its most proximal extent behind the apex of the sternocleidomastoid.

- •

In general, transverse cervical nerve roots are sacrificed, leaving only a sensory deficit for the patient.

Once the specimen has been removed, it is necessary to ensure hemostasis. The patient is often placed in Trendelenburg position and a Valsalva maneuver is implemented. In the case of significant dissection, lymphatic leaks may be evident and suture ligation of individual lymphatics is necessary. Although in recent years the advent of a multitude of different energy devices has prompted consideration of newer devices, potentially reducing the incidence of lymphatic leakage, this has not been borne out in any analysis to date. Topical sealants have not been shown to reduce the incidence of lymphatic leak either. The sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid may be mobilized and placed over leaky tributaries, if desired. In addition, a closed suction drain should be placed within the surgical bed.

Disease occasionally extends into the central neck, mediastinum, or below the clavicle, and this is evident via imaging or intraoperative findings. The presence of pathologically involved lymph nodes should direct the extent of surgery.

In general, hospital stay after cervical lymphadenectomy is brief, with patients discharged home on postoperative day 1. Patients should be given a diet before discharge in order to assess drain output for chyle. In the presence of high-volume lymphatic leaks (>200 mL per day), immediate surgical intervention with ligation of the involved lymphatic tributaries is recommended. For low-volume lymphatic leaks, patients can be placed on fat-restricted diets and drain output monitored. Drains are left in place until daily output is less than 15 mL, which is usually within 1 week.

Axillary Lymphadenectomy

A complete axillary dissection of levels I, II, and III with resection and evaluation of at least 20 nodes is routinely performed for melanoma. In an era when extent of surgery is being questioned, and in which as many as 80% of patients with sentinel lymph node–detected disease do not have additional disease at completion lymphadenectomy, at least 1 recent study has called into question the need for a level III dissection. Until additional data regarding this are available or MSLT-2 reaches maturity, the standard recommendations remain for complete dissection.

A lazy-S incision is used, beginning along the edge of the pectoralis major muscle and extending downward across the axilla. The incision continues inferiorly along the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The dissection extends superiorly to the tendinous portion of the pectoralis major and inferiorly to the junction of the latissimus and serratus muscles. The steps of dissection are as follows:

- •

Fascia along the lateral aspect of the latissimus is mobilized and dissection proceeds up to the insertion of this muscle, protecting the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle lying inferiorly.

- •

Fascia of the pectoralis major is mobilized and dissection performed posteriorly, accessing those nodes between the pectoralis major and minor (Rotter nodes) Fig. 2 .