Fig. 52.1

a Contrast CT demonstrating solitary liver lesion in the right hemi-liver detected on routine CT scan 4 years after lumpectomy for breast cancer. b Positron emission topography scan of the same patient showing a PET-avid lesion in the liver, with no extrahepatic disease

52.2 Hepatic Resection

Numerous small series have reported on outcomes after liver resection for breast cancer metastases. A 2011 systematic review [11] identified 19 studies over an 11-year period reporting on hepatic resection of at least ten patients. Hepatectomy was performed infrequently, with an average of 1.8 (range 0.7–7.7) cases per year in reported series. Although metastatic disease is now almost universally considered synchronous (with occult micrometastases already present at diagnosis and treatment of the primary), patients selected for resection had slowly progressive disease with a median time between diagnosis and resection of 40 months (range 23–77). Although the number of resections for breast cancer metastases was low, all were performed in high volume liver resection centres, and so mortality and morbidity after surgery were low at 0% (range 0–6%) and 21% (range 0–44%), respectively, in keeping with reported rates after resection for other liver lesions. Median overall survival from hepatectomy was 40 months (range 15–74) with a median 5-year survival rate of 40% (range 21–80). Although these results appear impressive, all the included studies were retrospective single-centre series without a comparator group. In addition, all used different patient selection criteria and medical treatment protocols, and so prognostic markers were difficult to identify. The authors suggested that a histologically positive margin after liver resection and hormone refractory disease were associated with inferior long-term outcomes, although the impact of case selection itself on outcome cannot be assessed and may have had a profound effect on observed survival rates as has previously been suggested in mathematical modelling studies [12]. In addition, the impact of improved systemic therapy for metastatic disease over the 11-year study period could not be assessed.

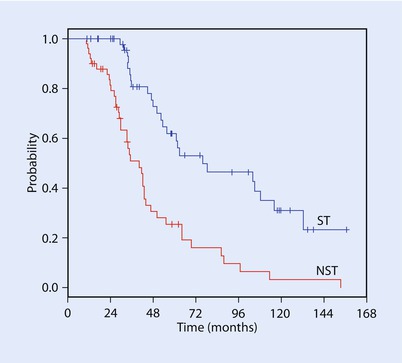

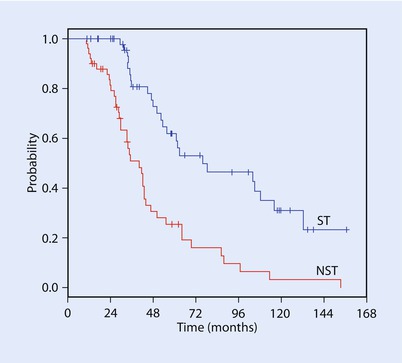

Since this review, two case-control series have been published that offer the advantage of a comparator group. Mariani and colleagues [13] reported a case-matched control study of 51 highly selected patients with stable breast cancer liver metastases and compared medical treatment alone versus surgery plus medical treatment. Patients were selected for surgery if they had technically resectable liver metastases (≤4) and demonstrated at least disease control with systemic therapy. No extra hepatic disease was allowed apart from controlled bone metastases. Patients were matched for known prognostic factors (such as stage, hormone receptor status and histopathological subtype) as well as the year of diagnosis to account for evolution in palliative treatment outcomes over time. The authors suggested that patients undergoing surgery plus systemic therapy had better survival compared with chemotherapy alone with a 3-year disease-specific survival of 81% versus 51%, respectively (P < 0.001) (see ◘ Fig. 52.2). Multivariate analysis suggested a relative risk of 3.04 (CI: 1.87–4.92) (p < 0.0001) in favour of surgical treatment, although median follow-up was not reported. The authors identified the nodal status of the primary disease, the number of regimens of systemic therapy to achieve disease control, the presence of bone metastases and surgical resection of liver metastases as independent prognostic markers of long-term survival.

Fig. 52.2

Mariani and colleagues performed a case control series which suggested improved overall survival after liver resection for breast metastases [13]. A statistically significant difference was dem-onstrated using the log-rank test (p < 0.0001) (Reprinted from Mariani et al. [13] with permission from Elsevier)

The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) group published a 167-patient case-control series comparing medically treated patients and those treated with surgical resection +/−ablation [14]. Patients were matched for ER status, adjuvant chemotherapy after breast surgery, adjuvant radiotherapy after breast surgery, treatment with hormonal therapy, number of metastases, time from breast cancer diagnosis to metastases and type of breast surgery. The selection for surgical intervention was performed on a case-by-case basis at a multidisciplinary meeting where a consensus concerning resectability and appropriateness of liver resection were determined. Most presented as metachronous disease, had one or two liver metastases, unilobar in distribution and a longer interval between breast cancer detection and diagnosis of metastases as compared to the medical cohort. Interestingly, the percentage of patients who underwent hepatectomy and/or ablation declined from 54% in the first half of the study period (1991–2002) to 36% in the latter half (2003–2014). Surgery was safe, with a 0% 90-day mortality and 23% 90-day morbidity. Patients in the surgical cohort more frequently had oestrogen receptor-positive tumours and received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for their primary breast tumour. The hepatic tumour burden was less, and the interval from breast cancer diagnosis to detection of metastases was significantly longer (53 months vs. 30 months) in the surgical cohort. Patients undergoing surgical treatment had a median recurrence-free interval of 28.5 months (95% confidence interval CI: 19–38) with ten patients (15%) recurrence-free after 5 years. Despite the high case selectivity (which appeared to increase through the study period), there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) between the surgical and medical cohorts (median OS 50 vs. 45 months; 5-year OS: 38% vs. 39%). However, over half the patients were free of recurrent disease and off chemotherapy for 2 years after resection, which the authors highlighted as having significant implications in terms of quality of life and cost of therapy. It is important to also note in this context that surgery and ablation are now safe therapies associated with short-lived and manageable morbidity.

Spolverato and colleagues [15] attempted to characterise this putative benefit further by performing a cost-utility analysis of liver resection combined with systemic therapy versus systemic therapy alone and suggested that liver resection in patients with breast cancer liver metastasis was cost-effective, particularly when used for oestrogen receptor-positive tumours or when newer biological agents (letrozole and palbociclib for ER + patients; docetaxel, trastuzumab or pertuzumab for HER2 + patients) were used. For example, Markov modeling suggested that for patients with ER+ disease, surgery combined with letrozole gave a net health benefit (a combination measure of survival benefit and incremental cost) of 10.9 quality-adjusted life months compared with chemotherapy alone. By contrast, resection plus chemotherapy was not as cost-effective for patients with HER2+ tumours with a net health benefit of 0.3 quality-adjusted life months compared with treatment with trastuzumab-based systemic therapy.

As well as formal surgical resection, there is limited evidence surrounding thermal ablation of breast cancer liver metastases. Meloni and colleagues [16] reported 52 patients undergoing ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation. Worryingly, local tumour progression occurred in 25% – significantly higher than the reported lesional recurrence rate after the ablation of colorectal liver metastases (≈4% [17]). Whether this is due to technical issues or differences in underlying disease biology remains unclear. The authors reported a median and 5-year survival rate of 30 months and 27%, respectively. Mack and colleagues [18] described a technique using magnetic resonance image-guided laser ablation using laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy applied in 232 patients where median survival was 52 months and 5-year survival was 41%, with a more reasonable lesional failure rate of 5%. However, comparisons with surgical resected or medically managed patients are impossible.

52.3 Radioembolisation

The unique blood supply of the liver, with portal flow supplying healthy hepatic parenchyma and arterial flow supplying metastatic disease, has led to the concept of delivering liver-only therapy in an effort to increase metastatic exposure to the agent whilst reducing the systemic dose and off-target side-effects. Radioembolisation involves the delivery of yttrium-90-loaded resin microspheres, which are pure β-emitters with a half life of around 65 h, to the liver in an effort to provide local radiotherapy (SIRT, selective internal radiotherapy). The total dose delivered depends on the number of microspheres delivered but is typically between 2 and 3 GBq.

Three retrospective studies have assessed the efficacy of SIRT in liver-limited breast cancer (see ◘ Table 52.1). Coldwell and colleagues [19] treated 44 women with symptomatic liver metastases (primarily RUQ pain) who had failed third-line systemic therapy and were not candidates for ablation or resection. Extrahepatic disease was also present in 66% of cases. A median of 2.1 GBq was delivered in a single session using SIR-Spheres microspheres (Sirtex Medical Ltd., Sydney, Australia). Eight patients (18%) required overnight hospitalisation for post-embolisation syndrome (consisting of pain and nausea), with no mortality. Imaging 6 weeks after SIRT demonstrated a 95% disease control rate. In the six patients who did not experience a measurable response on CT scan, survival was dismal (median 3.6 months). However responders experienced a longer survival, which, with a follow-up of 14 months, had not yet reached median.

Table 52.1

Survival after treatment with radioembolisation for breast cancer liver metastases

Investigator | n | Treatment type | ORR | SD | PFS | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prospective series | ||||||

Bangash et al. [22]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| ||||||