- Lifestyle interventions to improve glucose, blood pressure and lipid levels, and to promote weight loss or at least to avoid weight gain remain the underlying strategy throughout the management of diabetes even when additional medications are needed.

- Metabolic variables, such as HbA1c, post-prandial blood glucose concentrations, serum triglyceride and low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, can be used to suggest the most appropriate intakes of carbohydrate-containing foods.

- Vegetables, legumes, fruits and wholegrain cereal-based foods should be part of the diet because they are rich in dietary fiber, low in glycemic index or load and provide a range of micronutrients.

- In those treated with insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, the timing and dosage of medication should match the quantity and nature of carbohydrate to avoid hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Blood glucose self-monitoring may help to make appropriate choices.

- Saturated, trans-unsaturated fatty acids and dietary cholesterol should be restricted to reduce the risk for vascular disease, whereas oils rich in monounsaturated fatty acids as well as oily fish rich in n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are useful fat sources.

- In patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes without evidence of nephropathy, usual protein intake (up to 20% of the total energy intake) need not be modified. In those with established nephropathy, protein restriction to 0.8 g/kg normal body weight per day may be beneficial.

- Alcohol intake should be moderate.

- Alcohol intake should be moderate.

- Foods naturally rich in dietary antioxidants, trace elements and other vitamins are encouraged. Routine supplementation and the use of so-called special diabetic foods are not recommended.

- Individual dietary advice by physicians and dietitians and structured nutritional training are an essential part in the continuing treatment and education process of people with type 1 and 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Nutritional management in diabetes aims to assist in optimizing metabolic control and reducing risk factors for chronic complications. This includes the achievement of blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels as close to normal as is safely possible and serum lipid concentrations as well as blood pressure values that may be expected to decrease the risk for macrovascular disease. Individual therapeutic needs and the quality of life of the person with diabetes have to be considered when nutritional objectives are defined [1,2].

Diabetes health care teams should use the best available scientific evidence while giving dietary advice to the individual patient with diabetes. During recent years, the development of evidence-based guidelines in the management of type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has adopted a more formal approach to the evaluation of evidence underlying the guidance [3].

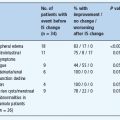

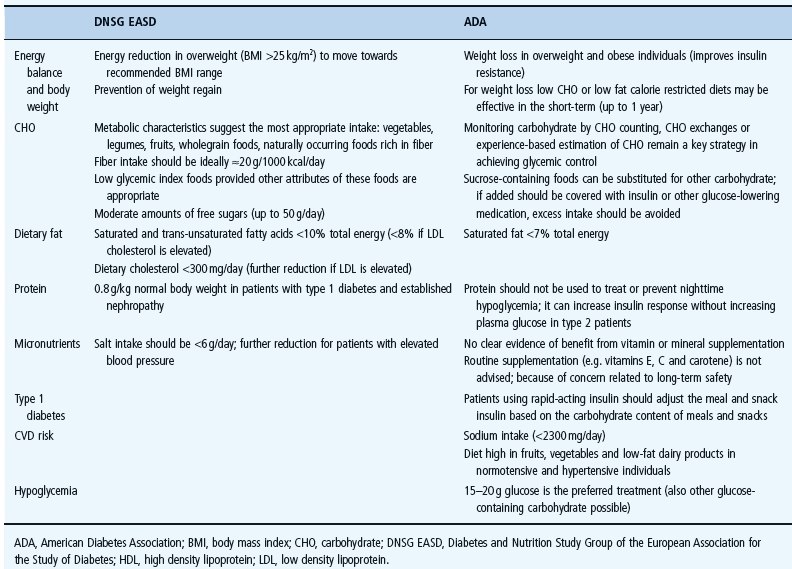

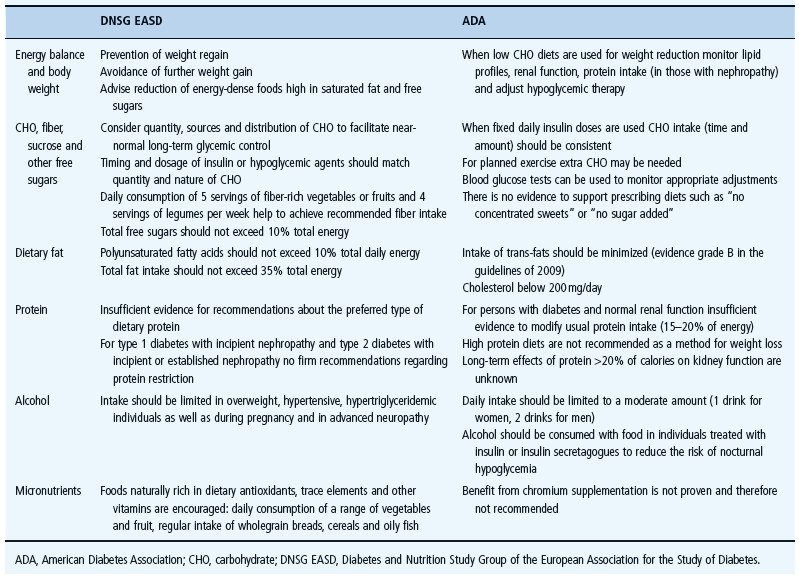

Currently available evidence-based nutritional recommendations for individuals with diabetes have involved a formal search of the literature using agreed sets of descriptors and relevant databases. The strength of evidence for the different nutritional recommendations is graded according to the type and quality of published studies as well as by statements from expert committees, which also take into account clinical experiences of respected authorities. Ideally, evidence-based guidelines are formulated from trials with fatal or non-fatal clinical endpoints; however, as this information is often not available, surrogate endpoints, such as glycemia, body composition, lipoprotein profile, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity and renal function, are frequently used to determine the potential of dietary modification to influence glycemic control and risk of acute and chronic complications of diabetes [1]. Tables 22.1–22.3 provide important dietary recommendations for people with T1DM and T2DM and the degree of evidence assigned to these recommendations by the Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (DNSG EASD) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Table 22.1 Nutritional recommendations with the evidence grade A for persons with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Evidence obtained from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials or at least one randomized controlled trial [1,2].

Table 22.3 Nutritional recommendations for persons with type 1 and type 2 diabetes with lower grades (C-E) of evidence. Evidence obtained from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experiences of respected authorities [1,2].

Energy balance and body weight

Controlling body weight to reduce risks related to diabetes is of great importance. When weight loss and increased levels of activity are achieved and maintained, in T2DM in particular, these interventions represent an established and effective therapeutic strategy for achieving target glycemic control [1,2,4]. Therefore, there is a consensus that such lifestyle interventions should be initiated as part of the treatment of new-onset T2DM [5–8]. Even modest weight loss, especially in abdominal fat, improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance and reduces serum lipid concentrations and blood pressure. Weight loss may lead to greater benefit for cardiac risk factors in people with a high waist circumference [1,4]. Visceral body fat, as measured by waist circumference, is used in conjunction with body mass index (BMI) to assess the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Overweight patients with T1DM may also become insulin resistant and weight reduction in these people may lead to a decrease of the insulin dose and improved glycemic control [1].

Prevention of weight regain is an important target in those who have lost some excess weight. Long-term restricted energy intake is necessary to sustain the metabolic improvements that can be achieved by weight reduction.

Losing weight is particularly difficult for those genetically predisposed to obesity. Nevertheless, the potential of structured weight loss programs should be exploited in overweight patients to achieve the possible beneficial effects [1,4,9]. Standard weight loss strategies plan 500–1000 fewer calories than estimated for weight maintenance. This may result in an initial loss of 0.5–1.0 kg body weight per week; however, many people regain the weight they have lost, and continued support by the health care team is needed to achieve long-term improvements of body weight and waist measurement. Advice concerning the reduction of high-fat and energy-dense foods, in particular those high in saturated fat and free sugars, will usually help to achieve weight loss. In addition, fiber intake should be encouraged. Regular physical activity should also be an important component of lifestyle approaches to the treatment of overweight. So far, the consensus by experts is that the use of very low energy diets, as an approach to promote initial weight loss, should be restricted to people with a BMI >35kg/m2 [1,2]. The evidence for recommendations regarding energy balance and body weight published by the ADA and by the DNSG EASD is summarized in Tables 22.1 and 22.3.

Macronutrient distribution in weight loss diets

The optimal macronutrient distribution of weight loss diets has not yet been established [2,10–12]. Low fat diets have been traditionally and effectively promoted for weight loss [1,13]; however, recently it has been demonstrated that low carbohydrate, higher fat diets may result in even greater weight loss over short periods of time, up to 6 months [2,10,14]. Although changes in serum triglycerides and high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were more favorable with low carbohydrate, higher fat diets than with high carbohydrate and lower fat diets in these trials, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was significantly higher in patients on high fat, low carbohydrate diets [2]. However, long-term metabolic effects of low carbohydrate, high fat diets are unclear and no controlled long-term trials are available to prove their safety with regard to CVD. Such diets eliminate several foods that are important sources of fiber, vitamins and minerals. It has also been shown that it was difficult to substitute monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) as the favorable fat source for carbohydrate because foods providing appreciable amounts of MUFA are limited, and even in Mediterranean areas, nowadays, people tend to consume undesirably high amounts of saturated fat in high fat diets. The ADA has summarized the current recommendations for weight loss in diabetes as follows: “For weight loss either low-carbohydrate or low-fat calorie restricted diets may be effective in the short-term (up to 1 year)” [2]. After initial weight loss it is important to avoid regain of weight [1].

Weight loss in the prevention of diabetes

With regard to weight loss in the prevention of diabetes in individuals at high risk for developing T2DM, lifestyle changes that included a reduced energy and a reduced dietary fat intake, and an increased fiber consumption together with regular physical activity (e.g. 150 minutes/week) [15,16] have shown improvements in several vascular risk factors including dyslipidemia, hypertension and markers of inflammation in addition to the significant reduction of the development of T2DM. So far, clinical trials on the efficacy of low carbohydrate diets for primary prevention of T2DM are not available.

Carbohydrate and diabetes

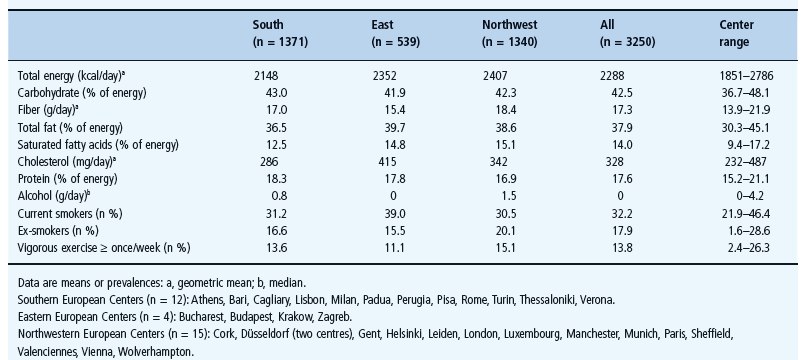

It is important that the advice for carbohydrate intake is individualized, based on the patient’s nutrition assessment, metabolic results and treatment goals [1,2,17–19]. There is a broad range of possible carbohydrate intake in people with diabetes (e.g. 45–60% of total energy intake). This advice is mainly based on recommended restrictions for the intakes of fat and protein. In many European countries, the mean carbohydrate intake of people with diabetes is only around 42% of total energy intake (Table 22.4) [20,21]. In the EURODIAB Complications Study, which included 3250 people with T1DM coming from 31 different European centers, the mean carbohydrate intake did not show major changes at the 7-year follow-up investigation compared with these intakes at baseline. Similar relatively low proportions of carbohydrate consumption and high intakes of total and saturated fatty acids have also been demonstrated in people with T2DM from the Mediterranean area [22,23].

Table 22.4 Nutritional intake and further life-style factors in persons with type 1 diabetes. Data are presented for the total EURODIAB cohort (31 centres, n = 3250) and different European regions [21].

Usually, carbohydrate intake in people with diabetes is lower than recommended by nutrition associations for the general population who receive advice to consume around 50% of total energy intake as carbohydrate. Many people with diabetes tend to reduce their carbohydrate intake because they fear an increase in blood glucose concentrations after the ingestion of carbohydrate-containing foods. In affluent countries, lower carbohydrate diets are usually accompanied by high fat, predominantly an undesirable high saturated fat intake. With such a diet it is also difficult to achieve sufficient fiber intake to meet recommendations [1,24,25]. Having this in mind, it does not appear to be productive to overemphasize the present renaissance of low carbohydrate strategies in diabetes. Furthermore, several recent reports on this topic do not clearly define what is meant by “low” or “high” carbohydrate and whether a carbohydrate intake of around 40% of total energy, which is consumed by many people with diabetes, already corresponds to a low carbohydrate diet [26,27].

Glycemic effects of different carbohydrate

Not only the amount of carbohydrate, but also the quality of carbohydrate is important for individuals with diabetes. Vegetables, legumes, fresh fruit, wholegrain foods and low fat milk products should be part of a healthy diet [1,2]. These foods provide also a range of micronutrients and fiber.

The amount of carbohydrate is an essential factor for postprandial glucose results in people with T1DM and T2DM [28–30]. In the process of achieving desirable glycemic control, many individuals with diabetes use either carbohydrate counting, carbohydrate exchanges or experience-based estimation of carbohydrate intake as a helpful means to monitor their consumption of carbohydrate at meals or snacks [2]. Different carbohydrates have different glycemic effects. Besides the amount of carbohydrate, other factors including the nature of starch, the amount of dietary fiber and the type of sugar influence the glycemic response to carbohydrate-containing foods [31–34].

The glycemic index (GI) of a carbohydrate-containing food describes its post-prandial blood glucose response over 2 hours in the area under the blood glucose curve compared with a reference food with the same amount of carbohydrate, usually 50g glucose (or white bread in some studies). Foods can be differentiated into high (GI: 70–100), average (GI: 55–70) or low (GI: <55) glycemic index foods; however, measured GIs are only available for a range of foods, with the data mainly coming from investigations in Canada and Australia. The glycemic load considers the amount as well as the quality of carbohydrate and is defined as gram of carbohydrate within the food multiplied with the GI of the food divided by 100.

It has been shown that the use of the GI or glycemic load of a food may confer moderate additional benefits-over that observed when only total carbohydrate is considered-not only for postprandial glycemia, but also for the lipid profile [2,35]. Therefore, foods with known low GI (e.g. legumes, pasta, parboiled rice, wholegrain breads, oats, certain raw fruits) should be substituted when possible for those with a high GI (e.g. mashed potatoes, white rice, white bread, cookies, sugary drinks) [36–39]. For example, eating fresh fruits is superior to a fruit juice with the same amount of carbohydrate. Low GI foods are only favorable, however, provided other attributes of these foods are also in line with a healthy nutrition [1]. Some foods with a low GI are high in fat and energy. Chocolates are such an example, with low GI but a high content of saturated fat. Some products specifically advertised for people with diabetes have reduced the GI of usual foods by replacing sucrose with sugar alcohols or fructose. A substantial benefit from these expensive so-called “diabetic” preparations has not been proven. Therefore, special foods for people with diabetes are not recommended. Proper food labeling may help the person with diabetes to make healthy choices from available usual foods.

Potential of dietary fiber

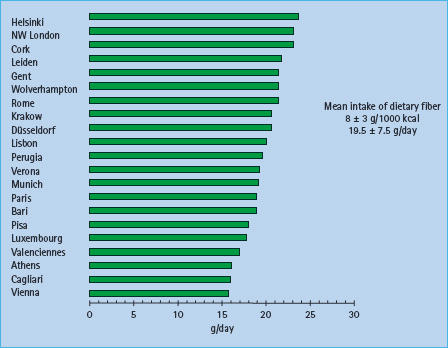

In many countries, people with diabetes consume only few foods that are rich in dietary fiber and therefore total fiber intake is much lower than recommended (Figure 22.1). With the relatively low carbohydrate intake in people with diabetes it is not easy to meet recommended quantities of fiber. Total dietary fiber intake in the EURODIAB Complications Study was on average only 8.0g/1000kcal or 19.5g/day [20,21]. People with diabetes should be encouraged to choose a variety of fiber-containing foods (vegetables, fruits, wholegrain products) to profit from the proven benefits for glycemic control, insulinemia and serum lipid concentrations [32–34,40]. Although total fiber intake was not high, epidemiologic data based on the EURODIAB Complications Study showed an inverse association between dietary fiber intake and HbA1c independent of possible confounders [32], an inverse association between fiber and LDL cholesterol and a positive association between fiber and HDL cholesterol. In addition, dietary fiber was inversely and significantly related to cardiovascular disease [34]. Dietary fiber was also associated with lower levels of BMI [26]. The degree of evidence for recommended carbohydrate and dietary fiber intakes is shown in Tables 22.1–22.3.

Figure 22.1 Fiber intake (g/day) in persons with type 1 diabetes (total n = 1102) from 21 centers in Europe. Data from EURODIAB Complications Study [20,21].

Sucrose and other sugars

Moderate intake of sucrose (<10% total energy) or other added sugars may be included in the diet of people with diabetes without worsening glycemic control [1,2,25,41]. Although fructose produces a reduction in post-prandial glycemia when it replaces sucrose, this potential benefit is tempered by the fact that fructose may adversely effect serum triglycerides as well as uric acid levels [1,8]. There is no reason to recommend that people with diabetes should avoid naturally occurring fructose (e.g. in fruits, vegetables or other foods) [1,2]; however, added fructose, added sugar alcohols or other nutritive sweeteners are energy sources that do not have substantial advantage over sucrose and therefore should not be encouraged. Higher quantities of sugar substitutes may promote undesirable gastrointestinal side effects. Furthermore, it is unlikely that energy-containing sugar substitutes such as sugar alcohols in the amounts likely to be consumed will contribute to an appreciable reduction in total energy intake although they are only partially absorbed from the small intestine [2,8].

Approved non-nutritive sweeteners may also be used by people with diabetes although a special long-term benefit in metabolic control has not been proven. Nevertheless, they are safe when acceptable daily intakes (ADI values) are followed [2,8].

Adjustment of insulin or insulin secretagogues to carbohydrate intake

For people who are treated with insulin or hypoglycemic agents, it is important to match the medication with the amount, type and time of carbohydrate intake to avoid hypoglycemia as well as excessive post-prandial hyperglycemia [1,2]. Individuals receiving intensive insulin treatment should adjust their premeal insulin dose based on the amount of carbohydrate in snacks or meals while considering also the GI of these foods [37,42,43]. This advice is now part of many nutrition education programs for people with diabetes who are treated with intensified insulin regimens [18,44]. Self-monitoring of blood glucose offers a helpful means of determining the most appropriate timing of food intake and to make optimal food choices [1]. Individual preferences and the needs of different treatment strategies remain the most important determinants of appropriate meal frequency, portion sizes and carbohydrate intake. Extra carbohydrate may be needed prior to exercise although adjustment of the insulin dosage in those on intensified insulin treatment is often an alternative and preferred choice. Structured training and continuing advice by the diabetes team is needed to enable the people with diabetes to adjust the insulin dosage while considering all three components: blood glucose results, amount and quality of carbohydrate intake as well as the degree of physical activity.

Dietary fat

The primary goal concerning dietary fat intake is to restrict the consumption of saturated fatty acids, trans-fats and dietary cholesterol to reduce the risk for vascular disease [1,2,45,46]. Compared with the non-diabetic population, people with diabetes have an increased risk of developing vascular disease. Fat modification in people with diabetes is an established principle to assist in achieving desirable serum lipid concentrations and to avoid vascular lesions in high-risk groups. Although most of this evidence is obtained from studies of people without diabetes, it seems that the recommendations are also relevant in the diabetic population as their risk for vascular disease is even higher than in the general population [1,47]. Even if statins are often needed to meet the treatment goals for serum lipid concentrations, possible lifestyle modifications should always be exploited, and remain the basic therapeutic approach to achieve a desirable lipid profile. The degree of evidence for the recommendations relating to the recommended amounts of fat intake or fat modification, respectively, is shown in Tables 22.1–22.3.

Reduction of saturated fatty acids

It is suggested that saturated fatty acids could be either replaced by carbohydrate foods rich in fiber or by unsaturated fatty acids, particularly by cis-monounsaturated fatty acids for people on a weight-maintaining diet. Such diets have been shown to achieve improvements in glycemia, insulin sensitivity and serum lipid values, compared to diets high in saturated fat [47–51].

Omega-3-fatty acids

Observational evidence supports the intake of n-3 polyunsaturated (omega-3) fatty acids as they have the potential to reduce serum triglycerides and have beneficial effects on platelet aggregation and thrombogenicity, thus offering cardioprotective effects [52]. A consumption of 2–3 servings of oily fish and plant sources such as rapeseed oil, soya bean oil and nuts will help to ensure an adequate intake of n-3 fatty acids [1,2,53,54].

Trans-fats and dietary cholesterol

Unfortunately, in most countries, the quantity of trans-unsaturated fatty acids is not well documented on many food products. The effects of trans-fats are similarly adverse as those of saturated fatty acids in raising LDL cholesterol. Therefore, their intake should be minimized [1,2]. Trans-fats are found in many manufactured products such as biscuits, cakes, confectionery, soups and some hard margarine. Food labeling informs whether hydrogenated fats and oils were added to a food product and the ranking of ingredients on the food label gives at least some information whether high quantities of trans-fats could have a role.

Data from healthy people and individuals with T1DM support the recommendation to restrict dietary cholesterol. With increasing intake, serum cholesterol levels may increase and contribute to the development of CVD [1,55].

Current fat intake in individuals with diabetes

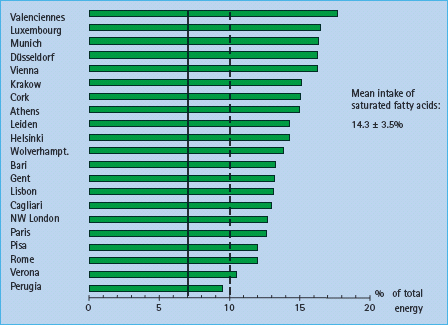

Fat intake data of European people with T1DM from the EURODIAB Complications Study demonstrated that on average the current target to keep the intake of saturated fatty acids below 7% of total energy was not achieved (Table 22.4). In the whole cohort of this study, the mean intake of saturated fatty acids was 14% of total energy (twice as high as recommended by the ADA) (Figure 22.2) [20,21], and even patients from the Mediterranean area who traditionally consumed a favorable fat intake no longer reach the goal to remain below 7% of saturated fat consumption [22,23]. In conclusion, fat modification remains an important target nutritional education topic to reduce the risk for vascular disease in people with both T1DM and T2DM.

Figure 22.2 Intake of saturated fatty acids (% of energy) in persons with type 1 diabetes (total n = 1102) from 21 centers in Europe. The solid vertical line marks the currently recommended upper limit of intake for saturated fatty acids by the ADA (7% total energy) The dotted vertical line represents the limit of 10% total energy for saturated fatty acids recommended by Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (DNSG EASD) in 2004. Data from the EURODIAB Complications Study. [20,21].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree