Major Concepts

Symptoms

In 1976, a frightening new severe respiratory illness emerged during a meeting of the American Legion in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that was later named Legionnaires’ disease and was found to result from a bacterial infection. In its early stages, Legionnaires’ disease is characterized by low-grade fever, headache, decreased energy, myalgia, and loss of appetite. Later symptoms include high fever, chills, cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain, vomiting and diarrhea, abdominal pain, rigor, and delirium. Infection often leads to a form of pneumonia that may be responsible for 15% to 30% of the cases of pneumonia treated in intensive care units. The causative bacteria may cause wound infections, pericarditis, endocarditis, and kidney impairment. A much milder, self-limiting form of infection is Pontiac disease, a flulike disease with fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgia, nausea, and a dry cough. This disorder is believed to be the consequence of an allergic response to dead bacteria.

Infection

Legionnaires’ disease is caused by infection with bacteria of the genus Legionella of the γ-2 subdivision of the family Proteobacteria, most commonly L. pneumophila and less often L. longbeachae. The bacteria are non-spore-forming, gram-negative rods with flagella. Forty-eight species of Legionella are known, and at least 20 of these are human pathogens. The bacteria have a complex life cycle that involves infection of freshwater protozoa and human monocytes and macrophages. They may also exist in biofilms. L. pneumophila inhabit natural and artificial water sources, including lakes, rivers, air-conditioning cooling towers, water-heating units, showerheads, grocery store misting machines, humidifiers, hot tubs, whirlpools, ventilators, and nebulizers. Infection results from inhalation of aerosols and sprays generated by these sources. Smokers and persons with respiratory illness are at higher risk for developing disease because they are less able to prevent aspiration of infectious droplets. Infants using respiratory equipment are also vulnerable. L. longbeachae may be acquired via cutaneous exposure to contaminated potting soil.

Immune Response

The innate and adaptive immune responses act in a cooperative manner to defend against infection with Legionella. The bacteria infect predominantly macrophages, triggering the toll-like receptors, which in turn stimulate the cells to produce the cytokine IL-12. IL-12 induces production of IFN-γ by Th1 helper cells. IFN-γ activates macrophages to generate reactive oxygen species that kill intracellular bacteria. The bacteria attempt to evade death by decreasing host production of IFN-γ.

Protection

Legionnaires’ disease is typically treated by either erythromycin or an azithromycin type of drug. Tigecycline is also protective in animal models. Treatment is usually effective if begun promptly. Preventive measures include stopping the smoking of cigarettes, wearing a HEPA-filtered mask when cleaning or collecting water samples from cooling towers, rinsing respiratory equipment with sterile rather than distilled water, and raising water temperature at the fixtures. Water sources containing the bacteria are often difficult to decontaminate but may be subjected to heat-and-flush treatment; chlorine, monochloramine, or ozone treatment; UV radiation, or copper-silver electrode ionization.

In 1976, a mysterious and sometimes lethal respiratory disease struck the city of Philadelphia, generating fears of widespread infection of unknown cause. That same year saw the reappearance of a strain of H1N1 influenza virus, antigenically similar to the virus responsible for the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, which left tens of millions of people dead throughout the world. The year also witnessed the appearance of another frightening and often fatal viral disease, Ebola hemorrhagic fever, in two unrelated outbreaks in Zaire (today’s Democratic Republic of Congo) and Sudan. The Philadelphia respiratory outbreak was later named Legionnaires’ disease and was found to result from exposure to Legionella species bacteria. These bacteria are also responsible for the mild, self-limiting Pontiac fever. Approximately 90% of Legionella exposures in the United States appear to involve Legionella pneumophila; this may be an overestimation because most diagnostic tests are specific to that particular species. In some outbreaks, a portion of infected individuals develop Legionnaires’ disease and the remainder experience Pontiac fever. In the United States alone, more than 25,000 cases of Legionnaires’ disease occur annually, resulting in 8,000 to 18,000 hospitalizations and more than 4,000 deaths. Although large outbreaks do occur (approximately 11% of cases), most incidences of this disease involve only a person or two. A preponderance of cases of the disease (90% to 98%), however, are believed to remain undetected. Since 1980, an annual average of around 350 cases have been reported to the CDC.

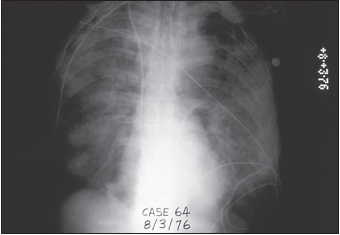

The first reported occurrence of Legionnaires’ disease was July 21–24, 1976, in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia. At that time, the hotel was hosting a meeting of the Pennsylvania branch of the American Legion. A total of 221 people became ill with bacterial pneumonia, two-thirds were hospitalized, and 34 (15%) died. The incidence of disease correlated with the amount of time spent in the hotel lobby.

Serological data available from a 1966 outbreak of acute pneumonia in a psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C., were later found to record antibodies to the bacteria linked to Legionnaires’ disease. That outbreak involved 94 cases with 16 deaths, for a fatality rate of 17%. Even earlier, a “rickettsia-like agent,” isolated in 1947, was later shown to be the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium.

More recently, a series of outbreaks occurred between July and October 1993 in Massachusetts (11 persons, 3 deaths), a state prison in Michigan (17 persons, 1 death), and Rhode Island (17 persons, 2 deaths), all of which were associated with cooling towers from which L. pneumophila serogroup 1 was cultured. This serogroup is the one most commonly recovered from the environment. Overall, Legionella bacteria may be cultured in up to 40% of cooling towers. In July and August 1994, the New Jersey State Department of Health informed the CDC of 14 cases of Legionnaires’ disease (and another possible 28 cases) in persons who had recently sailed to Bermuda on the cruise ship Horizon. This was the first report of Legionnaires’ disease from a cruise ship docking in a U.S. port. Whirlpool usage correlated with the development of illness, and Legionella was cultured from a sand filter used for recirculation of whirlpool water.

Many cases of Legionnaires’ disease are acquired by nosocomial transmission. Two hospitals (in Arizona and Ohio) were found in 1996 to have sustained transmission of this pneumonia for an extended period of time. In the Arizona hospital, 16 definite cases of Legionnaires’ disease (resulting after ten days of continuous hospitalization for a nonpneumonia illness) and 9 possible cases occurred between 1987 and 1996. Most of the patients had received either a heart-lung or bone marrow transplant (76%), and the others were either immunocompromised or had a chronic illness; 48% died during their hospitalization. L. pneumophila serogroup 6 was cultured from taps and showers in the patients’ rooms, from droplets small enough to be inhaled from air samples of the showers, from a carpet-cleaning unit from the transplant unit, and from the hospital’s hot-water distribution system and water softeners. In the Ohio hospital, 9 definite cases and 29 possible cases of Legionnaires’ disease were identified between 1989 and 1996. Of these, 39% had a chronic medical condition and another 34% were immunocompromised; 16% were inpatients on the psychiatric ward, and 29% died during their hospital stay. Nonpsychiatric cases were more likely to have received medication by nebulizer; however, only 40% were medicated by this route. This equipment was at times rinsed with tap water between doses. L. pneumophila serogroup 1 was cultured from both the psychiatric and nonpsychiatric buildings’ hot-water distribution systems, including potable water samples. Several rounds of decontamination were required to stop the nosocomial transmission at both hospitals.

Legionnaires’ Disease (Legionellosis)

Many persons with confirmed exposure to Legionella species seroconvert but nevertheless remain asymptomatic. Other persons develop Legionnaires’ disease, a severe multisystem disorder, an important feature of which is pneumonia. Approximately 2% to 5% of people exposed to the responsible Legionella species subsequently develop this disease manifestation. It is not uncommon, however, being found in 15% to 30% of pneumonia cases in intensive care units. After infection, an incubation period of two to ten days ensues. Early symptoms include low-grade fever, headache, decreased energy, myalgia, and loss of appetite. Subsequently, a high fever of 38.9°C to 40°C (102°F to 104°F), chills, productive or nonproductive cough, difficulty in breathing, chest pain, vomiting and diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rigor occur. Other manifestations include confusion, delirium, and dyspenia. In many cases, pneumonia results. Legionella-induced pneumonia is clinically indistinguishable from forms of pneumonia arising from other sources. Chest X-rays are inconclusive as well; however, alveolar infiltrates occur at higher frequencies in individuals with Legionnaires’ disease. L. pneumophila has also been associated with wound infections, pericarditis, endocarditis, and kidney impairment.

Fatality rates typically range from 5% to 30% in this form of Legionella infection. While even healthy people may present with this disease manifestation, the populations at greatest risk are smokers, heavy drinkers, the elderly and the immunosuppressed (including transplant recipients and individuals with cancer, diabetes, and kidney disease), and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. In nosocomial infections (about 23% of the total number of cases), fatality rates approach 40%. Procedures associated with Legionella infection include heart-lung or bone marrow transplants and rinsing respiratory equipment, such as nebulizers, with tap water.

Pontiac Fever

Most people (90% to 95%) exposed to L. pneumophila develop Pontiac fever rather than Legionnaires’ disease. Pontiac fever is a mild, self-limiting illness without symptoms of pneumonia. The incubation period ranges from hours to three days. Spontaneous recovery occurs after two to five days. No deaths have been reported from this form of the disease.

Pontiac fever manifests as a flulike illness in normally healthy people. Its symptoms include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgia, nausea, and a dry cough. Pontiac fever is associated with exposure to dead Legionella bacteria and may result from allergic responses to them.

The Bacteria

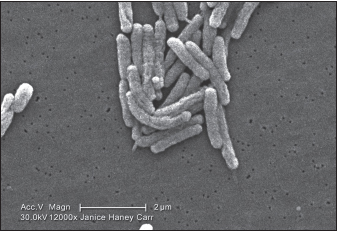

Legionnaires’ disease is caused by live bacteria of the genus Legionella of the γ-2 subdivision of the family Proteobacteria. The bacteria are non-spore-forming, gram-negative motile rods with lateral or polar flagella. Some 48 species encompassing 70 serogroups of Legionella are currently recognized; 20 species (39 serogroups) are known human pathogens. Most cases of Legionnaires’ disease, however, result from infection with L. pneumophila serotype 1, isolated in 1977. As early as 1943, Hugh Tatlock isolated strains of Legionella, using procedures designed for Rickettsia. In 1954, Wincenty Drozanski isolated a Legionella species from free-living soil bacteria. The organism most closely related to Legionella is Coxiella burnettii, another bacterial pathogen that causes Q fever.

FIGURE 9.2 Legionella pneumophila bacilli

Source: CDC/Margaret Williams, Claressa Lucas, and Tatiana Travis.

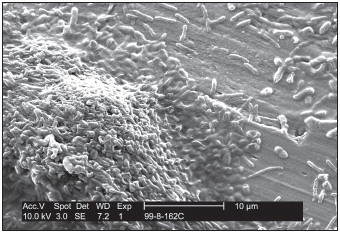

Legionella bacteria are intracellular parasites of freshwater protozoa (14 amoeba species, 2 species of ciliated protozoa, 1 species of slime mold) that live in artificial or natural warm-water systems with temperatures of 25°C to 42.2°C (77°F to 108°F). They grow best at 35°C to 45°C (95°F to 113°F). The bacteria were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 80% or more of the tested freshwater sites. In aquatic systems where the water temperature is artificially elevated, the balance between protozoa and bacteria is altered, with ensuing rapid bacterial growth. Increasing numbers of such systems over the past half century have made Legionella-induced illness, once extremely rare, much more common. Construction projects have also been sites of disease outbreaks as changes in water pressure led to descalement of plumbing systems. The bacteria similarly multiply within mammalian phagocytic cells, although such hosts are opportunistic. Most Legionella species survive within biofilms. One such biofilm contains Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pnuemoniae, Flavobacterium, and the amoeba Hartmannella vermiformis. The presence of the amoeba appears to be required for Legionella growth in this system.

FIGURE 9.3 Scanning electron micrograph demonstrating the association of Hartmannella vermiformis amoebas with Legionella pneumophila on a potable water biofilm containing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Flavobacterium

Source: CDC/Janice Carr.

Several genes of Legionella encode virulence factors involved in host cell infection. One such gene is mip, which codes for a 24 kilodalton homologue of FK506-binding proteins. Mip is required for infection of both amoebas and human phagocytic cells. Other such genes belong to the type IV secretion system of the Dot/Icm loci. Their products help in the transfer of plasmid DNA between bacteria by conjugation. Other genes are involved in bacterial survival and growth, such as pilE , pilD, mak, mil, and pmi that produce proteins found in bacterial flagella, kill macrophages, and allow infection of human and protozoan host cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree