Preoperative Preparation

Once a thorough history is obtained, a physical exam is performed. Palpable supraclavicular or inguinal nodes or the presence of hepatomegaly or ascites may preclude further operative intervention. However, tissue confirmation of widely disseminated disease is needed before abandoning potentially curative surgery. Digital rectal exam is performed in all patients. If a tumor is palpated, rigid proctoscopy should be performed to assess degree of circumferential involvement, potential for local (transanal) excision, and likelihood of sphincter preservation. Digital rectal examination may also reveal extraluminal tumor within the cul-de-sac which would also argue against radical curative surgery. Further assessment of the local extent of disease rectal neoplasms can be obtained with rectal ultrasound, whereby the degree of mural penetration and the presence of mesorectal nodal metastases can be determined with confidence. Routinecomplete blood counts and liver function tests,in addition to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA),are obtained in all patients. The CEA becomes useful when assessing the patient for tumor recurrence postoperatively. In the absence of obstruction or perforation, the entire lower gastrointestinal tract should be assessed with either a complete colonoscopy or a barium enema to rule out synchronous lesions.

A preoperative abdominal CT and serum transamnasesare not always necessary for a patient with normal physical exam (no hepatomegaly). However, systematic CT allows to eventually discover hepatic metastases and suspect adjacent organs invasion. The likelihood of occult liver metastases is low in these patients. However, in the subset of patients where liver metastases are suspected (weight loss, ascites, palpable liver), a physical exam reveals a large fixed abdominal tumor, and/or laboratory values are abnormal, a CT scan can be very useful in preoperative planning to rule out metastatic disease and involvement of adjacent organs.

For elective colon resections, the patient is usually admitted the day of surgery. Preoperatively the patient should be counseled about bowel preparation, which consists of a clear liquid diet the day prior to surgery and a mechanical bowel cleansing (oral cathartics or lavage). The use of oral nonabsorbable antibiotics is associated with significant gastric side effects and many surgeons choose to omit oral antibiotics in favor of intravenous antibiotics given perioperatively. On the morning of surgery, the patient may be given an enema to clear residual stool from the distal colon. The traditional Nichols protocol consists of 1 g of erythromycin base and 1 g of neomycin given at 1300,1400,and 2300 -hours the day before surgery.10 If a multiorgan resection is anticipated, the patient is admitted a few days before the operation, depending on his/her general state or specific preoperative examination or preparation.

If a stoma, either temporary or permanent, is being contemplated, it is essential that the site be marked preoperatively, taking into consideration certain important anatomic landmarks. It is advisable to mark both lower quadrants of the abdominal wall in the event that operative circumstances require ileostomy, rather than colostomy, placement. Performing this task before surgery helps the patient prepare emotionally for the possibility of a stoma and certainly is preferable to waking up after anesthesia finding a stoma in place. Frequently, the surgeon must mark the optimum site for a stoma, however, if their services are available, this task is better carried out by a trained enterostomal therapy nurse. The consequences of an improperly placed stoma can be more devastating than the effects of the operation itself, since the patient must live with the limitations imposed upon them which, if they are significant enough, could require further surgery to correct.

In choosing the proper site, one must avoid the groin, the waistline, the costal margins, the umbilicus, skin folds and scars. These all may interfere with appliance adherence and lead to stool leakage and skin breakdown. It is helpful to have the patient lie in the recumbent position and tense the abdominal wall; this helps to highlight the borders of the rectus sheath through which the stoma should be delivered at the time of surgery. The stoma should be placed in the middle of an imaginary triangle whose apices are the umbilicus, anterior superior iliac spine, and the pubis. The patient should then be placed in the upright position to determine whether the proposed site is still visible to them. Obese patients or those with a large pannus may find that the initial site is no longer visible in the upright position, consequently the site should be replaced in a more cephalad direction. It is also helpful to inquire as to the patient’s preference for clothing style, since the stoma should ideally be placed below the belt line. Lastly, it is helpful to place the appliance face piece for 24 hours to verify that it adheres to the abdominal wall during routine daily activities and the patient does not manifest signs of an allergic reaction to the appliance or the adhesive.

Since pulmonary embolism (PE) is a leading cause of in-hospital mortality following surgery, proper prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is essential. A variety of prophylaxis methods are available, the method chosen is determined by patient risk factors. Low risk factors include patient age less than 40 years, minor surgery lasting 30 minutes or less, and no associated conditions such as paralysis, malignancy, obesity, prolonged immobilization, history of varicose veins, or use of estrogens. For these patients, the postoperative incidence of calf DVT is less than 10%,proximal DVT less than 1%, and PE less than 1%. Prophylactic measures for these patients consist simply of early ambulation. Moderate risk factors include patient age greater than 40 years, duration of surgery longer than 30 minutes, and the presence of the associated conditions listed above. For these patients, the incidence of calf DVT is 10–40%, proximalDVT-2–10%, and PE 0.1–0.7%. Prophylaxis may consist of graduated compression stockings, sequential pneumatic compression devices, or low dose heparin (5000 u) administered subcutaneously 2 hours before surgery and every 12 hours thereafter. Rare complications of low-dose heparin include skin necrosis and thrombocytopenia. Patients at highest risk have factors including the moderate factors listed above and those undergoing orthopedic operations, pelvic or abdominal cancer operations, have a prior history of DVT or PE and those with hereditary or acquired coagulopathies such as protein C and S deficiencies, antithrombin III deficiency, or anticardiolipin antibodies. For these patients, the risk of calf DVT is 40–80%, proximal DVT10–20%, and PE 1–5%. For the patients at highest risk, a combination of graduated compression stockings, sequential pneumatic compression devices, and subcutaneous heparin is recommended. Low molecular weight heparin may be used but this may have a higher incidence of bleeding and is more expensive.11,12

Operative Technique

Operative Technique

Although regional anesthesia may be used exceptionally for high-risk patients, general endotracheal intubation is the preferred method. After induction, a Foley catheter is placed; postoperatively, it can be removed once the volume status of the patient has stabilized. For operations that involve a pelvic dissection, the Foley catheter should remain in place for up to 5 days. Ureteral catheters are not routinely inserted. They are, however, selectively employed in patients who are undergoing reoperative procedures where scarring and abnormal tissue planes may make identification of the ureters difficult. Ureteral catheters can also be helpful when operating on bulky tumors or tumors that invade the retroperitoneum or kidney. Although ureteral stents aid in identifying the ureters either by palpation or illumination, they should not lull the surgeon into a false sense of security. Furthermore, successful identification of the ureter at one location, e.g., upper abdomen, does not guarantee that the same ureter can be spared from injury at another anatomic location or time during the same operation. It is important to remember that there is no substitute for careful dissection when working around the ureters.

The patient is placed in a supine position and the legs are positioned in stirrups to allow transperineal access to the rectum and pelvis. Pressure points, especially the lateral aspect of the legs, are padded. A midline incision allows easy access to the abdomen and provides excellent exposure with adequate retraction. A midline incision is also ideal if a stoma becomes necessary because it leaves both sides of the abdomen free for placement. Some surgeons prefer a transverse incision. However, this provides somewhat limited access to the abdomen and is less ideal for stoma placement. For better access to the operative site and pelvis, slight Trendelenburg positioning, rotation of the table, and packing of the upper abdominal viscera with a lap pad will help keep the small bowel out of the operative field.

Once the abdomen is opened, careful and systematic exploration will allow one to determine the extent and involvement by the primary tumor. Adjacent visceral involvement should be assessed to determine if an en bloc resection is possible. The liver and peritoneal surfaces should be assessed for metastatic disease. Small scattered liver metastases should not preclude palliative resection, however, if extensive disease is present, resection may not be advisable.

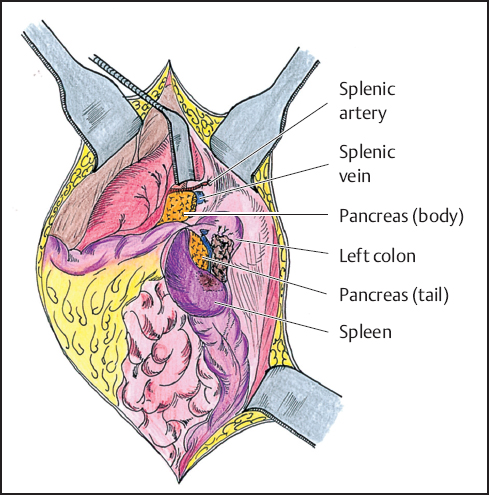

Fig. 9.1 Example of splenic flexure tumor invading the tail of the pancreas. The flexure is mobilized en bloc with the spleen and tail of the pancreas. The body of the pancreas is oversewn or stapled.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree