Major Concepts

Symptoms

Lassa virus causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF) in approximately 20% of infected persons. Although the mortality rate is only 1% overall, it climbs to 15% to 20% in hospitalized patients and 60% in persons who are untreated. Symptoms include joint and lower back pain, severe muscle pain, headache, a nonproductive cough, epigastric pain, vomiting and diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, myocarditis, and hemorrhagic manifestations. Severe cases of disease may report edema of the face and neck, conjunctival hemorrhaging, mucosal bleeding, central cyanosis, bradycardia, pleural effusions, hepatitis, and encephalopathy with neurological manifestations. Large amounts of blood loss result from hemorrhaging and movement of fluid into the tissues, potentially leading to shock or death. Unlike most other hemorrhagic fevers, pathology during LHF is not associated with the production of large necrotic lesions or inflammation but rather results from loss of function of platelets, endothelial cells, monocytes and macrophages, and lymphocytes. Approximately 25% of individuals with LHF develop some degree of hearing loss, which is often permanent. Infection during pregnancy usually results in death of the fetus or the mother (or both).

Infection

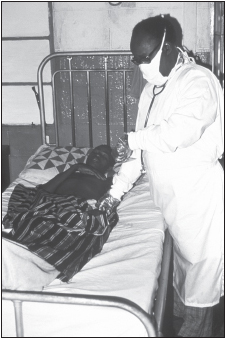

Lassa virus is an Old World arenavirus. It is considered a BioSafety Level 4 organism and is closely related to the New World arenaviruses responsible for the American hemorrhagic fevers as well as several nonpathogenic Old World viruses that infect humans. Lassa virus is endemic to several West African countries, where the annual incidence of infection is 100,000 to 500,000, resulting in approximately 5,000 deaths per year. A rodent, the multimammate rat, serves as the reservoir host for Lassa virus, as is the case for other pathogenic arenaviruses. Humans may be infected by internalization of rat excreta via inhalation or ingestion, by being bitten by an infected rat, or during the preparation or eating of rats. Human-to-human transmission also occurs via exposure to body fluids or clinical samples or by sexual contact with an infected male. Nosocomial infection is also common.

Immune Response

Lassa virus inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-8. This state of immunosuppression appears to aid in viral evasion of the immune response. Lassa virus infection of monocytes and macrophages is responsible, in part, for decreased immunity because infected cells are less able to produce proinflammatory cytokines or to express major histocompatibility complex type I molecules. These latter aid in activation of CD8+ killer T lymphocytes, which are among the most important forces behind host antiviral activity. Other arenaviruses that do not alter cytokine production are not pathogenic to humans.

Protection

Ribavirin is the drug of choice in the treatment of LHF and is fairly efficacious when administered early after the beginning of symptomatic disease. A newer drug, T-705, appears to be less toxic and is effective when given to patients with advanced disease. Several candidate vaccines have been developed. Some of these use live, avirulent viruses, while other vaccines incorporate Lassa virus glycoprotein or nucleoprotein genes (or both) into a vaccinia virus vector. This latter approach may be problematic in that inoculation with vaccinia-based vaccines may prove fatal to immunosuppressed individuals, and HIV infection is common in regions endemic for the Lassa virus.

Lassa virus, the causative agent of Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF), is a member of a family of viruses, the arenaviruses, which cause severe hemorrhagic fevers with high fatality rates in people from Africa and the Americas. Lassa virus is the most prevalent member of the family that infects humans: it is estimated to infect 100,000 to 500,000 people in West Africa annually. Most infections are asymptomatic, but LHF causes a severe and potentially fatal disease in individuals who do report symptoms. Many residents in some regions have developed antibodies to the virus, suggesting past undetected infection. The reservoir for Lassa virus is a rodent that is common in large areas of Africa, including many areas in which LHF has not yet been reported. Because the rodent frequently enters human habitations and is considered a delicacy among inhabitants of the region, contacts between humans and this rodent are very common. The large geological range of the viral reservoir, the frequency of interactions with humans, the low rate of overt disease, and the presence of other causes of hemorrhagic fever in Africa suggest the possibility that asymptomatic or otherwise undetected infections may be occurring in other areas of Africa. Furthermore, a new arenavirus that causes hemorrhagic fever in humans has recently been identified in South Africa and Zambia. Arenaviruses and arenavirus-associated hemorrhagic fevers may thus pose a more serious threat to the health of residents of Africa than previously suspected.

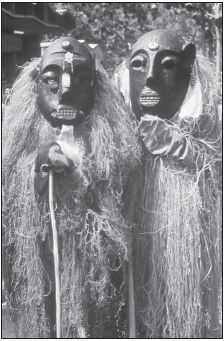

FIGURE 14.1 Lassa witch doctors

Note: The causes of infectious diseases are often not understood by residents of developing areas of the world who may turn to traditional healers for treatment.

Source: CDC.

A small number of cases have been found in people from Europe and North America after they have visited West Africa. LHF has been tested by some groups for use as a bioweapon, as has been the case for other related viral hemorrhagic fevers. Nonendemic regions of the world thus need to be prepared to deal with potential outbreaks of this disease in the future.

The first reported cases of LHF occurred during 1969 in a missionary hospital in Nigeria in western Africa. A nurse became infected while manually clearing secretions from the mouth of the first known Lassa fever patient. Infectious material entered her body through a cut on her finger. Within a week, she was acutely ill and died three days later. Sixteen secondary infections were reported at that time.

A larger outbreak occurred in 1996 in which 470 persons became ill in Sierra Leone and the fatality rate among the hospitalized was 23%. In the first four months of 1997, a total of 328 persons were hospitalized, with a 14.6% fatality rate. The 1997 epidemic originated by human consumption of food that had been contaminated by rodent urine and later cases resulted from human-to-human transmission. In that year, the blood of health care workers from six centers in Nigeria was screened for the presence of antibodies to Lassa virus: 12.3% of those tested showed signs of past infection, the highest rate being among ward aides. Cases of Lassa fever have also been seen in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, and Israel. Some infected individuals were residents of Africa who were transported to Europe or North America for medical care. Other infected persons had traveled to western Africa as students, soldiers, or members of a peacekeeping force in Sierra Leone.

In September and October 2008, an outbreak of a new type of viral hemorrhagic fever occurred in Zambia and South Africa caused by the Lojo virus. This is the only Arenavirus reported to cause disease in southern Africa. The first known cases involved a paramedic (the index case), the person cleaning his room, and the nurse caring for the index case. These reports were followed by the infection of a safari agent and her nurse. Four of the five infected individuals died. The nurse caring for the paramedic received ribavirin and recovered. None of the other patients received this antiviral drug.

Infection with the Lassa virus is usually asymptomatic or mild, and the proportion of infected individuals who become ill ranges from 9% to 26%. Among those who become symptomatic, many will develop a severe, multisystem disease that may result in death or permanent disability. Hundreds of thousands of infections occur annually in western Africa, resulting in approximately 5,000 deaths. In some areas of Sierra Leone, LHF is responsible for 10% to 16% of hospital admissions, and as much as 40% of the general population has antibody to the virus, indicating previous exposure or infection.

Disease severity is related to viral load. Pathogenic manifestations differ from those of filovirus-induced hemorrhagic fevers (Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers) and appear to result from alteration of cellular functions rather than an inflammatory response or the presence of lesions. Endothelial cell, platelet, and lymphocyte functions are suppressed, resulting in loss of fluid from blood vessels, decreased blood coagulation, hemorrhaging, and reduced antiviral immunity, including suppressed production of proinflammatory cytokines.

The virus initially replicates at the site of infection, generally the lungs or the bloodstream, if acquired through a break in the skin. During later stages of the disease, high levels of virus are found in the lymphatic system, including the spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. Very high viral titers have been reported in the mammary glands and placenta, and the ovaries, lungs, kidneys, adrenal glands, and myocardium of the heart are also infected. Unlike the case of Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers, infection of these organs does not result in significant production of lesions. After an incubation period of one to three weeks, infected individuals present with chills and high fever, exudative pharyngitis, weakness, and generalized malaise. This is followed by the gradual onset of joint and lower back pain, severe muscle pain, headache, a nonproductive cough, epigastric pain, vomiting and diarrhea with abdominal discomfort, myocarditis, and hemorrhagic manifestations, such as bleeding from the gums, nose, and lungs. Petechiae, pinpoint skin lesions, may be found on the upper chest, shoulders, and neck. Laboratory findings often include early lymphopenia, late neutrophilia, abnormal platelet functions, hemoconcentration as fluid leaves the circulatory system, and proteinuria (the presence of protein in the urine) due to kidney dysfunction. Jaundice and skin rash are rare.

After one week, individuals with mild infections begin to recover and the more severe cases begin to deteriorate. The most severe cases may be accompanied by edema of the face and neck, conjunctival hemorrhaging, mucosal bleeding, central cyanosis (bluish color), bradycardia (slowed heart rate), pleural effusions, hepatitis, and encephalopathy. Neurological manifestations may include intention tremors of the tongue, pharynx, larynx, and later, the extremities, followed by generalized convulsions. Loss of blood volume due to hemorrhaging and fluid entering the tissues may result in shock or death. In some of the early cases of LHF, death occurred about a week after the development of symptoms. Findings during the autopsy of those individuals included fluid in the lungs; enlarged pale livers; congestion of the heart, spleen, and kidneys; and a low number of lymphocytes. Although the overall mortality among infected persons is 1%, the mortality rate among hospitalized patients is much higher (15% to 20%) and approaches 60% among those who are not treated. Transient hair loss and ataxia (unsteady movement) may occur during recovery. Unlike the case with other hemorrhagic fevers, 25% of persons developing LHF experience some degree of unilateral or bilateral eighth cranial nerve deafness. Only half of these recover some degree of function after one to three months.

LHF is particularly severe for pregnant women and their fetuses. If infection occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy, a spontaneous abortion will usually result. If infection takes place during the third trimester, however, both mother and fetus typically will die. This unusual severity may result from the extremely high viral titer found in the placenta. The precise cause of death in these cases remains unknown as pathological lesions are not found in infected fetuses.

Lassa virus is a member of the Old World group of Arenaviridae

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree