(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

Management of the regional lymph nodes in clinically localized melanoma remained controversial from 1892, when Show [1] advocated the routine node dissection of the regional nodes, until the early 1990s, when the technique of intraoperative lymphatic mapping (LM), sentinel lymphadenectomy (SL), and selective complete lymph node dissection (SCLND) pioneered by Morton et al. [2], resolved this issue definitively. In this period, the proponents of the orderly, sequential spread of melanoma cells to the regional nodal basin first and then through the thoracic duct(s) into the bloodstream and distant organs supported routine elective node dissection, believing that a certain percentage of patients with melanoma metastatic to the regional nodes without detectable hematogenous dissemination to distant organs could be cured of their disease [3, 4]. Proponents of the hypothesis that melanomas often metastasized directly into the bloodstream without a prior “incubation” period in the regional nodes supported a policy of observation of the regional nodes, with surgical intervention if the nodes clinically grew to palpability. Retrospective studies tended to show higher survival in patients with elective dissection for microscopically positive lymph nodes than for patients who underwent therapeutic dissection of palpable positive nodes. However, three prospective, randomized studies showed no survival benefit for patients undergoing elective lymph node dissection (ELND) compared with those on observation who underwent therapeutic dissection upon clinical development of enlarged regional lymph nodes [5–7]. The most recent randomized study, by Balch et al. [8], showed survival improvement with ELND in patients without ulceration of the primary melanoma, those less than 60 years of age, and those with tumor thickness 1.0–2.0 mm. But this study also showed no overall improvement in survival for patients with ELND. On the other hand, knowledge of the histologic status of the regional nodes has been recognized as the most significant prognostic criterion for survival and therefore is a valuable indicator of the advisability of adjuvant therapy, being an important stratifying parameter in any adjuvant study of clinically localized melanoma.

The problem with ELND has been the appreciable rate of surgical complications suffered by patients and the cost of this treatment, considering that only about 20 % of the patients had microscopically positive nodes. The other 80 % were subjected to an unnecessary procedure because of our inability to determine the histological status of the regional nodes with less invasive means.

Since 1977, cutaneous lymphoscintigraphy has been increasingly used for trunk melanomas in order to identify the lymph basins at risk of metastasis [9]. During lymphoscintigraphy, one will often observe a lymphatic channel leading to a lymph node. (Occasionally two channels lead to two nodes.) On mere theoretical consideration, the lymphatic channels issuing from a melanoma site would not be likely to be connected to and drain their lymph to all lymph nodes of the nodal basin simultaneously or nearly so, but rather to communicate with one node or occasionally two. The lymph they carry is filtered through these nodes to higher-echelon nodes and finally into the bloodstream. Any cells in the lymph are likely to be trapped in the first lymph node, from which, after some growth, they can spread to higher nodes and the bloodstream. Feline experiments provided visual confirmation of the flow of a patent blue V dye to a single node, the sentinel node (SN), from which the dye could travel to higher echelons of nodes [10].

In the initial clinical study by Morton et al. [2], 223 patients with localized cutaneous melanoma underwent lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymphadenectomy (LM/SL) using isosulfan blue or patent blue V dye. SNs were identified in 82 % of basins. Complete node dissection was performed in all patients to ascertain that for all patients with negative SNs, the rest of the nodes were also negative. Only 2 (1 %) of 194 basins had metastases confined to nonsentinel nodes, apparently owing to some failure in the application of this technique to identify all sentinel nodes. A false negative rate of 1 % is reassuringly low, of course, but given that the rate of microscopic regional involvement for patients with localized melanoma is about 20 %, it is clear that the false negative rate (i.e., the rate at which the technique misses a positive sentinel node, when present) is 5 %.

Technique of Sentinel Node Biopsy

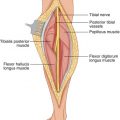

To avoid distortion of the lymphatic flow from the primary site or at the nodal basin, local anesthesia is avoided; general or regional anesthesia is preferred. According to the technique originally described by Morton et al. [2], 1–2 mL of vital blue dye, isosulfan blue (Lymphazurin) is distributed by intradermal injection at four sites around the primary lesion or biopsy incision. The injection site is gently massaged for 4–5 min. The incision at the regional basin is made in the same location and orientation as for node dissection but is shorter in length. A skin flap is then raised in the direction of the primary site, searching in the subcutaneous fat for afferent, blue-stained lymphatic channels arriving from the primary site, which one may follow to a blue-stained lymph node (sentinel). The adjacent nodes are also examined to rule out the presence of a second SN, which would have to be removed. If a blue-stained lymphatic channel or node is not identified after 20 min of dissection, the injection of the blue dye is repeated at the primary site, and the dissection is resumed after 5 min [2].

The original technique of SN biopsy was later supplemented in all patients with preoperative cutaneous lymphoscintigraphy and the use of an intraoperative gamma probe. With the concomitant use of an intraoperative probe, Morton’s group [11] modified the technique of dissection by following the guidance of the probe directly to the SN without raising any flaps. Colloidal antimony trisulfide is used in Australia, human albumin nanocolloid in some European centers, and technetium-99m (99mTc)–labeled albumin colloid (CIS-US, Inc., Bedford, MA), 99mTc sulfur colloid (CIS-US), or 99mTc human serum albumin (Amersham Mediphysics, Arlington Heights, IL) in the United States. About 18.5–30 MBq (0.5–0.8 mCi) of radiopharmaceutical is injected at four sites around the primary site [12]. A scintillation camera follows the drainage pattern from the primary site to the regional lymph nodes. SNs are identified often within 30 min. By 4 h, it becomes difficult to differentiate between SNs and nonsentinel nodes because the radiocolloid migrates to higher-echelon nodes while retaining the glow of its radioactivity. The nuclear medicine physician (NMP) marks on the patient the skin area corresponding to the SN(s) depicted on the screen.

A few observations regarding lymphoscintigraphy: (1) The marking on the skin of the SN location at the basin by the NMP is often 2 or more centimeters away from the hottest spot identified by the gamma probe. The site indicated by the probe is the correct one. Sites marked by the NMP that contain no differential radioactivity by the probe may be ignored. (2) If the radiocolloid injected around the primary site does not migrate to a regional basin within 2 h, one may wait up to 3 h or so after injection, as infrequently the migration to the basin takes this long. (3) If the radiocolloid does not migrate to a nodal basin anatomically consistent with the location of the primary lesion, it may be worthwhile to use the probe to check the nodal basin likely to be draining the primary site, on an anatomical clinical basis, by sliding the receiving end of the probe slowly over the entire skin area covering the basin, looking for a spike in radioactivity that may indicate the SN site. In melanomas of the head and neck area, the NMP uses the perceived “hot” spot on the screen to mark the corresponding site on the skin, but this mark may be grossly inaccurate. One should rely on the gamma probe, which can be slowly carried over the entire neck area from the primary site to the clavicle and can pinpoint the location of the SN.

The radiocolloid injection is helpful in several ways: (1) to demonstrate the nodal basin(s) draining the primary site; (2) to pinpoint with the use of a handheld gamma probe the site of SNs at the basin, so that the incision is centered over the hot spot; (3) to guide the dissection intraoperatively as the probe points toward the SN site; and (4) to suggest or disallow the presence of additional SNs, depending on the amount of relative residual radioactivity at the basin after removal of the SN. Thus, removal of all blue-stained nodes and nodes with greater than 10 % of the hottest node’s radioactivity leads to a low nodal recurrence rate because in most instances all SNs have been completely removed [13]. Removal of all blue nodes and all nodes with radioactivity counts that are greater than the background radioactivity of the nodal basin has also been used successfully as a criterion [11].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree