Staging is the classification used to define the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality. Cancer staging is useful for assessing prognosis and defining care for individuals and for defining the changes in cancer incidence and outcome for populations. A number of classifications systems for defining the extent or “stage” of cancer are used worldwide, each with its own historical basis and purpose. Three systems are used widely in the United States: the Extent of Disease (EOD) system used by the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER); the Summary Stage system used primarily by state cancer registries; and the Tumor, Node, Metastases (TNM) system. The EOD and Summary Stage systems are used by population registries primarily for the purpose of population cancer surveillance. These systems generally do not change over time, allowing evaluation of temporal changes in cancer incidence and presentation.

The TNM staging system is based on the major morphologic attributes of a tumor that determine its behavior: size of the primary tumor (T), presence and extent of regional lymph node involvement (N), and presence of distant metastases (M). It includes 4 classifications: clinical, pathologic, recurrence, and autopsy. Clinical classification (cTNM) is based on evidence that is gathered before initial treatment of the primary tumor, and is used to make local/regional treatment recommendations. It includes physical examination, imaging studies (including mammography and ultrasound), and pathologic examination of the breast or other tissues as appropriate (usually needle biopsies) to establish the diagnosis of breast cancer. Pathologic classification (pTNM) includes the results of clinical staging, as modified by evidence obtained from surgery and from detailed pathologic examination of the primary tumor, lymph nodes, and distant metastases (if present). It is used to assess prognosis and to make recommendations for adjuvant treatment. Classification of a recurrent tumor (rTNM) includes all information available at the time when further treatment is needed for a tumor that has recurred after a disease-free interval. Autopsy classification (aTNM) is used for cancers discovered after the death of a patient, when the cancer was not detected prior to death.

TNM staging is the most clinically relevant staging system and is used primarily to support clinical decision-making and for evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, TNM undergoes periodic revision to maintain its clinical relevance. This allows incorporation of advances in the understanding of factors affecting cancer prognosis. The TNM system is maintained and revised by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Interanationale de Cancer Controle (UICC). These groups empanel disease-site expert teams that recommend changes to TNM and publish TNM revisions every 6 to 8 years. The sixth edition was effective for patients diagnosed after January 1, 2003. The next revision (the seventh edition) will be published in October 2009, to be effective for cancers diagnosed on or after January 1, 2010 and is described at the end of the chapter.

Earlier in 2000, a Breast Task Force consisting of 19 internationally known experts in breast cancer management was convened to recommend revisions for the breast cancer chapter of the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.1 While the general standards for defining the tumor, nodes, and metastases were largely unchanged, major changes were made in the definition of lymph nodes with minimal involvement and for the classification of nodal metastases defined by the then-new technique of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).

Undoubtedly the most controversial change in this area is the assignment of a strict size criterion to distinguish isolated tumor cells (ITCs) from micrometastases. There are conflicting data about the clinical importance of these very small entities. With increasing numbers of patients being diagnosed with very small primary tumors and minimal lymph node involvement, answering this question is more important than ever. The majority of these patients, up to 75%,2,3 may have no need for systemic therapy, but finding the cutoff point between this group and the 25% who will prove to have more aggressive disease has been problematic.

To facilitate the collection of clinical outcome data that would be comparable across studies, the sixth edition of the AJCC defined strict quantitative criteria to separate ITCs, micrometastases, and macrometastases. Has this strategy been successful over the ensuing 5 years? To some extent it has, but problems have surfaced.

In this chapter, we will provide a brief overview of the major changes in breast cancer classification in the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, followed by a review of recent papers examining clinical outcomes as a function of size of lymph node metastases. We will assess some of the problems that have arisen in implementing these changes, and consider what the future might hold for breast cancer staging.

Review of Major Changes for Breast Cancer Staging in the Sixth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual

The revised staging system for breast cancer adopted for the sixth edition, has been discussed in great detail elsewhere.4-8 The definitions relating to tumor size are unchanged from the fifth edition. Definitions related to distant metastases are largely unchanged, except that the M1 classification no longer includes metastases to ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes (reclassified as N3). Overall stage groupings are also largely unchanged, except that breast disease classified as T1-4/N3/M0 has been moved from stage IIIB to a new stage IIIC.

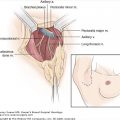

Changes related to method of detection, size, number, and location of regional lymph node metastases are summarized in Table 13-1. The changes related to the number and location of lymph node metastases were made to reflect published data and widespread clinical consensus. On the other hand, changes related to method of detection and size of metastasis are an innovative component in the sixth edition, in that they are directed toward the future collection of data about the clinical importance of these characteristics.

| Changes Related to Method of Detectiona |

|---|

Identifiers have been added to indicate the method of detection of lymph node metastases: |

Sentinel lymph node dissection—(sn) |

Molecular techniques—(mol+) or (mol−) |

Changes Related to Size of Regional Lymph Node Metastases |

Micrometastases are distinguished from isolated tumor cells on the basis of size: |

Micrometastases are defined as tumor deposits larger than 0.2 mm but not larger than 2.0 mm and classified as pN1mi |

Isolated tumor cells are defined as tumor deposits not larger than 0.2 mm and classified as pN0 |

Changes Related to Number of Axillary Lymph Node Metastases |

Major classifications of lymph node status are defined by the number of affected axillary lymph nodes: |

Metastases in 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes are classified as pN1 |

Metastases in 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes are classified as pN2 |

Metastases in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes are classified as pN3 |

Changes Related to Location of Regional Lymph Node Metastases |

Metastases to the infraclavicular lymph nodes are classified as N3 |

Metastases to the internal mammary nodes are classified as pN1, N2/pN2, or N3/pN3, based on the size of the lesion and the presence or absence of concurrent axillary lymph node metastases |

Metastases to the supraclavicular lymph nodes are classified as N3 |

In the fifth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual,9 micrometastases were defined as metastatic lesions no larger than 2.0 mm and recognized as clinically relevant. While many have hypothesized that there would be a lower size limit below which lesions would no longer be clinically important, there were insufficient data to test this hypothesis. To answer this need, the sixth edition defined a new size class called “isolated tumor cells” (ITCs) that were no larger than 0.2 mm and classified as pN0(i+). Micrometastases were redefined as lesions larger than 0.2 mm but no larger than 2.0 mm and classified as pN1mi. Importantly, this size classification is the only defining characteristic used in the AJCC classification. Method of staining (immunohistochemical [IHC] or hematoxylin & eosin [H&E]) and location of the metastases were not included in the definitions for micrometastases or ITCs. (In practice, virtually all ITCs are detected by IHC, but they may be verified by H&E staining. While it is technically possible that an ITC might be detected initially by H&E, it is unlikely.) Because of this strict, quantitative definition, it was hoped that subsequent studies examining the effects of small metastases on outcome could be more easily compared.

Nine studies published from 1993 to 2008 reported outcomes associated with micrometastases and/or ITCs in any axillary lymph node (Table 13-2).10-18 In most studies published after 2003, the size criteria specified in the sixth edition were used, while precise definitions of ITCs and micrometastases varied in earlier studies. Although most of these studies are still not strictly comparable, they support the decision to classify ITCs as pN0, with 6 of 8 studies that looked at ITCs reporting no clinical importance. The results were mixed for micrometastases: of the 7 studies that looked at micrometastases, 4 reported a significant clinical impact and 3 reported no impact. Across all 9 studies, outcomes associated with ITCs and micrometastases were not consistently related to tumor size, follow-up time, or whether patients received systemic therapy.

| Study | No. Patients | Median Follow-up (mo) | % Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy | % Patients with Tumor Size > 2 cm | Size of Nodal Deposit | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasser et al, 199310 | 159 | 132 | 0% | N.A. | ≤ 0.2 mm | Survival rate comparable to those without occult metastasis |

| > 0.2 mm | Recurrence, DFS, OS significantly worse than those without occult metastasis | |||||

| Colpaert et al, 200111 | 104 | 92 | 0% | 50% | ITCs vs larger deposits, all < 2 mm | No significant correlation between either type of occult metastasis and prognostically important features of the primary tumor (eg, size and grade) |

| Cummings et al, 2002 12 | 208 | 120 | 2% | 38% | No mets | 80% DFS; 80% OS |

| ≤ 0.5 mm | 75% DFS, RR = 1.17; 78% OS | |||||

| > 0.5 mm | 48% DFS, RR = 7.98; 60% OS | |||||

| Millis et al, 200213 | 477 | 227 | <1% | 50% | IHC only (0.01-0.03 mm) vs H&E (0.01-2.9 mm) vs missed (1.8-10 mm)b | Overall survival and relapse-free survival not related to the presence of occult metastases, regardless of size |

| Umekita et al, 200214 | 148 | 84 | 61% | 58% | No mets | 93% DFS; 96% OS |

| < 0.1 mm | 71% DFS; 76% OS | |||||

| Susnick et al, 200415 | 48 | 180 | 10% | 0% | ≤ 0.2 mm | OR for distant metastasis = 2.1 (p = 0.31) |

| > 0.2 mm and ≤ 2.0 mm | OR for distant metastasis = 9.5 (p = 0.04) | |||||

| Kahn et al, 200616 | 214 | 96 | 5% | 45% | ≤ 0.2 mm or node negative vs > 0.2 mm and ≤ 2mm | No significant difference between groups in OS or DFS |

| Chen et al, 200717 | 209,720c | 120 | N.A. | 22%-43%d | No mets | 76% OS |

| ≤ 2.0 mm | 71% OS | |||||

| > 2.0 mm | 65% OS | |||||

| Tan et al, 200818 | 368 | 211 | 0% | 33% | No mets | DFS 81% |

| ≤ 0.2 mm | DFS 64% | |||||

| > 0.2 mm and ≤ 2 mm | DFS 41% |

Since the publication of the sixth edition, SLNB has become the treatment standard for a large percentage of breast cancer patients, especially those with minimal disease. Overall, patients with no metastases detected in the sentinel node are unlikely to have metastases in other nodes, while approximately 50% of patients with sentinel node metastases will prove to have additional lesions in the non-sentinel nodes. However, it appears that the probability for non-sentinel node metastases is in part a function of the size of the sentinel node lesion. Thus, very small lesions are less likely to predict for additional metastases, and should be associated with better outcomes. This is reflected in 6 studies published since 2004 that have reported no significant effect on local recurrence, relapse-free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, or overall survival in association with ITCs in the sentinel node (Table 13-3).19-24 Note that several of these studies define ITCs as those lesions that are positive for IHC and negative for H&E, rather than measuring the lesions.

| Study | No. Patients | Median Follow-up (mo) | Size of Nodal Deposit | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imoto et al, 200419 | 164 | 53 | SLN negative vs SLN IHC+/H&E−, ≤ 2.0 mm | No significant difference between SLN negative and SLN IHC+ in 6-year RFS |

| Chagpar et al, 200520 | 84 | 40 | SLN negative vs SLN IHC+/H&E−, median size of met = 0.5 mm | No significant difference between SLN negative and SLN IHC+ in 5-year OS or DMFS |

| Fan et al, 200521 | 390 | 31 | SLN negative | LR 3.3% |

| SLN H&E positive, ≤ 2.0 mm | LR 2.2% | |||

| SLN H&E positive, > 2.0 mm | LR 8.7% | |||

| Langer et al, 200522 | 224 | 42 | SLN negative or lesions ≤ 0.2 mm, IHC and/or H&E | LR 0.8% |

| > 0.2 mm and ≤2.0 mm, IHC and/or H&E | LR 0% | |||

| > 2.0 mm, IHC and/or H&E | LR 1.4% | |||

| Hansen et al, 200723 | 624 | 73 | SLN negative vs | No significant difference among 3 groups for 8-year OS or DFS |

| SLN IHC+/H&E− vs | ||||

| SLN H&E positive, ≤ 2.0 mm | ||||

| Herbert 200624 | 16 | 30 | ITC | No recurrence during follow-up et al, period |

Although these data indicate that ITCs are probably not associated with poor outcomes, it is somewhat disappointing that the recent literature continues to be highly variable, especially with respect to the clinical relevance of micrometastases. Even though the size distinctions used to define ITCs and micrometastases in the sixth edition were highly specific, there have been problems in standardizing implementation.

When the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual was being formulated, SLNB for breast cancer patients was still in its final validation stages, and methods had not been (and still are not) standardized. With respect to SLNB, the sixth edition specified only that if this technique was used, then a descriptor (sn) was to be added to the pathologic classification. What has become clear in the last 5 years is that there is wide variation in how SLNB is implemented among different institutions.

In the pre-SLNB era, most patients, except those whose disease was very limited, received full axillary lymph node dissections, usually removing 10 or more nodes per patient. The standard was to bivalve the retrieved nodes, examining 1 or 2 H&E-stained sections per node. With SLNB, only those nodes believed to provide the primary lymphatic drainage from the identified tumor are harvested, typically only 1 or a few nodes per patient. However, these nodes are examined in much greater detail, using multiple sections per node and employing immunohistochemical staining instead of, or in addition to, H&E staining. Not surprisingly, the number of very small lesions detected has gone up dramatically, as approximately one-third of patients who are negative on H&E evaluation will be positive on serial sectioning and IHC staining.25

Unfortunately, the exact methodology for pathologic examination of the sentinel nodes differs from institution to institution, and sometimes from pathologist to pathologist. There are differences in the number of sections that are examined and the thickness of the sections. Some practitioners continue to use only H&E, others use IHC only in cases that are H&E negative or for certain types of cancers (eg, lobular cancer), and still others use IHC on all patients.

Practitioners also differ in whether a completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) should be recommended in patients with a finding limited to ITCs or micrometastases in the sentinel node. As many as 10% of patients with ITCs may have additional metastases in non-sentinel nodes,26 and elaborate nomograms, based on characteristics of the metastatic lesion and of the primary tumor, are being constructed to better predict the possibility of additional non-sentinel metastasis.27 Some feel that expanding the radiation field to include the axilla will provide sufficient control. In addition, results of a limited number of studies suggest that non-sentinel node metastases are unlikely in patients with sentinel node ITCs and very small primary tumors (T1a,b).28-33

Pending the availability of long-term outcome data from large ongoing clinical trials (ACOSOG Z0010, ACOSOG Z0011, ALMANAC, EORTC AMAROS, and IBCSG 23-01), patients and their physicians should discuss the risk of non-sentinel node metastasis as a function of sentinel node status. For the patient with a small primary tumor (T1a,b) in conjunction with ITCs in a single sentinel node, the omission of axillary surgery may be suggested, with XRT used as a substitute for completion ALND, raising the tangential port to include the lower axilla. For patients with larger primary tumors with or without more extensive lesions in the sentinel node, lymph node status has little or no impact on the choice of systemic treatment options, which are primarily based on characteristics of the primary tumor (eg, size, grade, hormone, and HER2 status). However, with larger tumors, the risk of additional nodal metastases may be higher, leading most practitioners to advise full axillary dissection for women with a positive sentinel node.

The strict size criteria laid out in the sixth edition to distinguish ITCs from micrometastases were intended to assist in generating comparable data about the clinical importance of microscopic lesions. In practice, this strategy has achieved only moderate success. There are a variety of reasons for this, broadly divided into 2 overlapping categories: (1) failure to use the recommendations of the sixth edition; and (2) confusion about how to implement the recommendations, especially in areas in which the sixth edition did not provide enough information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree