Infections in Long-Term Care Facilities

Nimalie D. Stone

Chesley L. Richards Jr.

INTRODUCTION

Long-term care is broadly defined as “an array of health, personal care, and social services, provided over a sustained period of time to persons with chronic conditions and with functional limitations” (1). While these services can be provided in the home and community settings, the focus of this review will be on infection control issues that are relevant to licensed longterm facilities (LTCFs), mainly certified nursing facilities (nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities). In contrast to acute care facilities, LCTF residents generally stay in the facility from several weeks to years, and in some instances may represent the final home for many individuals. Consequently, staffing and policies are oriented toward maximizing function, independence, social function, and resident and family satisfaction. The traditional LTCF resident is a cognitively or functionally impaired elderly adult. However, recent trends have seen increases in the number of individuals entering LTCFs to receive postacute care services (e.g., rehabilitation following a surgical operation or acute illness) or skilled nursing services (e.g., intravenous antimicrobials, parenteral or enteral nutrition, or aggressive wound care) following a hospitalization. This chapter will review LTCF characteristics, selected infections in LTCF residents and facilities, and infection control issues in LTCF.

CHARACTERISTICS OF LTCF RESIDENTS, STAFF, AND CLINICIANS

LTCF CHARACTERISTICS

In the United States, >40% of adults will reside in an LTCF at some point during their life (2,3). Of 3.3 million people who spent time in certified nursing facilities in the United States in 2009, most were female (65%), age >75 years (69%), and white (83%); however, the population of nursing facility residents is becoming more ethnically diverse and proportion of people <65 years is increasing (4). Additionally, >50% of residents in nursing facilities require extensive support with activities of daily living, such as toileting, bathing, eating, dressing, or transferring.

In 2004, the median stay in nursing facilities was 463 days, and most residents came from a hospital (36%) or private residence (29%) (5). However, a growing proportion of residents are entering nursing facilities from hospitals. In a cohort of 230,730 newly admitted residents in 9,738 nursing facilities, 70% entered the facility following discharge from hospitals with Medicare coverage for skilled care (6). In 2005, only 27% of unique individuals admitted to a certified nursing facility for the first time remained in the facility >90 days (7). The rise in admissions receiving postacute, skilled nursing services suggests that nursing facilities are no longer serving as destinations, but often are bridging the transition between hospitalization and return to home in the community.

LTCF staffing is lower than staffing in acute care hospitals. Nationally, LTCFs have one-third the number of full- or part-time employees (1.7 million vs. 5.0 million) at acute care hospitals (8), even though there are more LTCFs than acute care hospitals (15,700 vs. 5,800) and >50% more LTCF beds. Of the 900,000 nursing staff working in LTCFs, >600,000 are certified nurse’s aides (5). Consequently, nurse’s aides provide the bulk of direct resident care in most LTCFs, while registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) supervise overall care and provide medical services, such as medication distribution. Especially during evening/night shifts or during weekends, a typical 100-bed LTCF may have only one or two RNs or LPNs on duty. Improving the ratio of nursing staff to residents and expanding the presence of RNs has been proposed as important steps toward improving the quality of care in nursing homes (1).

Less than 20% of LTCFs have a physician on staff and direct medical care rarely is provided by physicians. The majority of physicians (77%) do not spend time caring for nursing home residents (9). For physicians who provide nursing home care, the median effort is 2 hours per week, or approximately 4% of the physicians’ overall practice time. Very few physicians (3%) spend >5 hours per week providing medical care in nursing homes. Barriers to optimal medical practice in LTCFs by physicians include inadequate documentation, lack of nursing support, and insufficient reimbursement (10). Consequently, nonphysician clinicians provide much of the direct medical care in LTCFs. In a national survey of LTCFs, 63% reported having nurse practitioners with a median of two nurse practitioners per facility (11). On-site nonphysician clinicians can reduce hospitalizations of LTCF residents and overall costs (12,13).

In addition to practicing clinicians, each nursing home is required to have a medical director who is responsible for providing “oversight and participate in drug utilization review and quality assurance programs and to work with attending physicians on appropriate drug therapies and medical care issues” (1). Most medical directors are either internists or family physicians and on average spend 10 to 20 hours per month performing medical director responsibilities, which include infection control and resident safety. At a national level, the American Medical Director’s Association (AMDA) is the primary professional organization for medical directors and provides training and certification for medical directors (14).

LTCFs often have consultant pharmacists on staff or available by contract who evaluate medication prescribing in the facility and provide consultation regarding drug therapy issues. In most LTCFs, consultant pharmacists perform mandatory medication reviews and provide feedback to the LTCF administrator and medical director. Consultant pharmacists may offer an important on-site perspective and expertise in improving the management of a wide range of medications, including antimicrobials, and should be seen as a potential resource for clinicians and medical directors regarding antimicrobial management (15). During disease outbreaks in LTCFs, consultant pharmacists also may provide valuable resident and family counseling regarding medication side effects or support regarding the distribution of prophylactic antimicrobials (e.g., oseltamivir) (16).

FACTORS THAT IMPACT PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF INFECTIONS IN LTCFs

RESIDENT POPULATION

Many of the residents in LTCFs have underlying risk factors which increase their susceptibility to infections. Age-related changes to immune functioning (immunosenescence), chronic diseases, and malnutrition all interact to diminish host defenses to infections and blunt response to preventative measures like vaccination (17,18). Cognitive deficits, functional impairments (e.g., fecal and urinary incontinence, immobility, diminished cough reflex), and frailty also increase vulnerability to infections by limiting an individual’s ability to maintain personal hygiene and increasing dependence on caregivers (19) (Table 29.1). Medical interventions, such as indwelling devices and wounds, have been shown to increase the risk of infection (20,21). Indeed, with the growth of subacute or postacute care, many LTCFs now have residents receiving medical care (e.g., central venous catheters, hemodialysis, parenteral antimicrobial or nutrition therapy, or mechanical ventilation) equivalent in complexity to interventions performed in many acute care hospitals.

TABLE 29.1 Individual-Level Risk Factors for Infection in LTCF Residents | |

|---|---|

|

Challenges identifying infections arise because LTCF residents may present atypically. A study assessed the clinical signs and symptoms of older adults (>75 years) with bacteremic urinary tract infections and found 10/37 (27%) did not mount a fever >37.9°C and 48.6% failed to report any localizing urinary tract symptoms (e.g., dysuria, urgency or frequency) (22). A large study reviewing clinical presentations of nursing home residents with and without radiologic evidence of pneumonia found that cough and sputum production did not discriminate between residents with and without pneumonia, while new somnolence or confusion seemed more prevalent among those with confirmed evidence of pneumonia on X-ray (23). Therefore, nonspecific signs and symptoms should prompt further investigation for potential infections in this population, and absence of typical clinical signs of infection may not reliably rule out an infection being present.

FACILITY ENVIRONMENT AND STRUCTURE

Although there are increases in the short-term skilled nursing and rehabilitation services being provided, the majority of LTCFs continue to serve as primary residences for a population of frail and aging individuals who are no longer able to reside independently in the community. Culture-change and resident-centered care movements advocate for the creation of a “home-like” environment to reduce the institutional feel of these facilities (24). Communal living arrangements, such as a dining hall, resident lounge, and group activities, all foster socialization and enhance relationship building among residents, staff, and visitors both in and outside the nursing home. However, the frequent close interactions within large groups of individuals and use of shared equipment also can facilitate the spread and acquisition of communicable infectious diseases through both direct person-to-person spread and indirect exposure to contaminated surfaces and materials (25,26).

LTCF staffing and other processes of care also may have impact on the risk of infections among residents. Studies have identified turnover among RNs and low staff levels of all levels of nursing staff including aides have been associated with increased risk of infection among residents and more frequent receipt of infection control program deficiency citations during facility inspections (27,28). In a study of outbreaks among New York LTCFs, institutional risk factors for respiratory or gastrointestinal infection outbreaks included larger homes (risk ratio 1.71 per 100 bed increase), nursing homes with a single nursing unit, or with multiple units but shared staff. Risk for outbreaks was lower in LTCFs with paid employee sick leave (29).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SELECT INFECTIONS IN LTCFs

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

A study estimated the burden of infections occurring in LTCFs to range from 1.6 million to 3.8 million annually (30). Data used to calculate these burden estimates were limited

to reports from research studies involving small numbers of facilities using different methodologies to define infections. Additionally, these studies exclusively represent skilled nursing facilities and nursing homes (SNF/NH) and were conducted many years ago. With the rising number of individuals receiving more complex medical care in SNF/NHs, it is possible that these numbers underestimate the true magnitude of infections in this setting. Data are lacking from other settings, such as assisted living facilities or senior residential care settings. Most infection rates are calculated only for endemic infections and fail to account for the many infections related to outbreaks which frequently affect this population. Morbidity and mortality due to infections in LTCF is substantial. Infections are among the most frequent causes of transfer to acute care hospitals and 30-day hospital readmissions from LTCF (31,32). Infections also have been associated with increased mortality in this population (33,34).

to reports from research studies involving small numbers of facilities using different methodologies to define infections. Additionally, these studies exclusively represent skilled nursing facilities and nursing homes (SNF/NH) and were conducted many years ago. With the rising number of individuals receiving more complex medical care in SNF/NHs, it is possible that these numbers underestimate the true magnitude of infections in this setting. Data are lacking from other settings, such as assisted living facilities or senior residential care settings. Most infection rates are calculated only for endemic infections and fail to account for the many infections related to outbreaks which frequently affect this population. Morbidity and mortality due to infections in LTCF is substantial. Infections are among the most frequent causes of transfer to acute care hospitals and 30-day hospital readmissions from LTCF (31,32). Infections also have been associated with increased mortality in this population (33,34).

Providers working in LTCFs face many challenges in identifying and initiating appropriate management for suspected infections. As outlined above, underlying conditions commonly affecting LTCF residents result in atypical manifestation of infections and difficulties eliciting clinical signs and symptoms. Clinical providers are frequently off-site and therefore make management decisions based on the assessments communicated by front-line staff. The use of surrogate assessments and the lack of immediate access to provider follow-up likely drive antimicrobial use and frequent hospital transfers. Many facilities have limited diagnostic testing (e.g., laboratory or radiology) available for febrile or potentially infected residents. Most laboratory services are contracted out to a local hospital or reference laboratory which can lead to delays in obtaining specimens, processing, and reporting results back to providers. To address the challenges faced by providers working in LTCF, several clinical guidelines outlining the evaluation and criteria for defining infections in nursing home residents have been published (35,36). Implementation of these guidelines could standardize the process for evaluating residents with suspected infection to ensure appropriate information is being identified and communicated by nursing staff to clinical providers.

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS (UTIs)

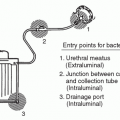

UTIs account for 25% to 30% of all bacterial infections in LTFC residents and are among the most common bacterial infections in LTCF residents (21,37). Although ordinarily the bladder is sterile, many older individuals have alterations in the functionality of the urinary tract due to medical conditions (e.g., stroke, diabetic neuropathy, prostate hypertrophy) that result in incomplete emptying of the bladder, urinary retention, and chronic bacteriuria. The use of urinary catheters to manage urinary drainage issues also facilitates bacterial entry into the urinary tract. The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), bacteriuria without localizing signs or symptoms of infection, ranges from 25% to 50% in noncatheterized LTCF residents and 100% among those with long-term urinary catheters; ASB is accompanied by pyuria (e.g., ≥5 white blood cells/high power field on direct microscopic exam of the urine) in >90% of instances (37). Therefore, use of pyuria or bacteriuria as indicators of UTI in frail elderly patients or catheterized patients without clinical symptoms is not recommended. The unreliable clinical assessment for infections in LTCF residents coupled with the diagnostic uncertainties in differentiating

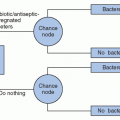

ASB from infection contributes to inappropriate antimicrobial use and its related complications. Suspected UTIs account for 30% to 60% of antimicrobial prescriptions in the LTCF setting (38,39,40). Antimicrobial use for prevention or treatment of ASB in LTCF residents, does not confer any long-term benefits in prevention of symptomatic UTI or improving mortality, but has been shown to increase the incidence of adverse drug events and result in subsequent infections with antibiotic-resistant pathogens (41).

RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS (RTIs)

Similar to UTI, RTIs are frequently reported and are a major driver for antimicrobial use. In a 3-year surveillance study of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) outbreaks in 5 LTCFs, the overall rate of LRTI was 1.75 per 1,000 resident-days (range within different nursing homes 1.4 to 2.8), with 43% of those infections occurring in the context of an outbreak (42). Antimicrobial use for LRTI can be as high as 50% with appropriateness ranging from 87% for pneumonia to only 35% for episodes of acute bronchitis (42,43). Morbidity and mortality associated with outbreaks of LRTIs in LTCFs can be significant. Between 2000 and 2002, LRTIs were the leading infectious disease cause of both hospitalization and death among people >65 years old (44). In a cohort study of 353 LTCF residents with LRTI, 22% were transferred to the hospital and 9% died within 30-days of infection (45).

The variety of bacterial and viral pathogens which cause LRTIs in LTCFs creates a unique set of challenges for prevention and control. The cognitive and functional impairments (e.g., difficulty swallowing, impaired cough, limited mobility, oxygen dependence) increase an individual’s risk for pneumonia and other LRTIs. The impaired immunity of elderly persons, allows viral upper respiratory infections (URIs) which are generally mild in adult populations to cause significant disease in LTCF residents (46). Clinical presentation of LRTIs in LTCFs may not discriminate severe viral infections from pneumonia, so early implementation of respiratory precautions for residents with cough and fever, until a definitive diagnosis has been determined, may help reduce transmission of communicable infections.

INFLUENZA AND OTHER VIRAL RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS

Although influenza is the most commonly reported cause of LRTI outbreaks, many respiratory viruses which are not generally thought to cause severe infections in adults have emerged as significant causes of LRTIs in LTCFs (47). Parainfluenza virus, human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human adenovirus, and rhinoviruses all have been implicated in outbreaks of LRTIs in nursing home settings, with attack rates as high as 50% to 70% (46,48,49,50,51,52). While most commonly occurring in the winter season, influenza and other respiratory viruses can circulate throughout the year, and small off-peak outbreaks can be missed by surveillance programs (42). Use of molecular-based respiratory diagnostic testing for viral LRTIs (e.g., multiplex polymerase chain reaction assays), could increase the identification of respiratory viruses causing LRTI outbreaks and hasten initiation of appropriate management. However, even before a causative pathogen has been identified, LTCFs should be proactively implementing infection control

measures, such as use of respiratory droplet precautions, cohorting of symptomatic residents, and enhanced surveillance for LRTI symptoms among residents, healthcare personnel (HCP), and visitors, to reduce the spread of infection throughout the facility.

measures, such as use of respiratory droplet precautions, cohorting of symptomatic residents, and enhanced surveillance for LRTI symptoms among residents, healthcare personnel (HCP), and visitors, to reduce the spread of infection throughout the facility.

Vaccination of residents and HCP is one of the main cornerstones of preventing influenza outbreaks in LTCFs. Studies have demonstrated preventive efficacy rates of influenza vaccination in elderly residents of LTCFs to be 23% to 43% for influenza-like illness, 0% to 58% for influenza, 46% for pneumonia, 45% for hospitalization, 42% for death from influenza or pneumonia, and 60% for death from all causes (53,54). Since 2005, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has required that certified nursing homes offer residents annual influenza vaccination and started reporting vaccine coverage rates among residents as a quality measure. A recent study of patterns in influenza vaccination coverage in certified nursing homes showed that although the median coverage was 73%, there was evidence of significant differences in vaccine coverage between black and white residents, as high as 10%, at the state level due to lower vaccination rates in facilities which cared for a predominantly black resident population (55). This finding highlights the importance of culturally appropriate strategies for promoting influenza vaccination in LTCFs. Improving rates of HCP influenza vaccination in LTCFs also has been associated with better outcomes among residents during outbreaks (56,57,58). In a national survey of clinical nursing assistants (NA) working in LTCFs, only 37% reported receiving influenza vaccine. Multivariable analysis showed longer tenure in the facility, higher numbers of benefits offered by the facility, and self-reported feeling of being “respected/rewarded for their work” as factors which increased receipt of vaccine (59). Facilities which actively work to promote HCP influenza vaccination can show improvements in coverage, however, barriers which must be overcome include individual perceptions of the risks and benefits to the vaccine as well as facility-level factors such as staff turnover (60).

PNEUMONIA

Nursing home acquired pneumonia (NHAP) is one of the leading infectious causes of hospitalization and death in the LTCF population (61). In a 3 year prospective cohort study in 5 LTCFs, the rate of NHAP was 0.7/1,000 resident-days, with 31% requiring hospitalization and 9% dying within 14 days of the diagnosis (62). Many risk factors for NHAP result from aging and/or underlying conditions, such as impaired swallowing or cough reflex, advanced dementia, malnutrition, functional decline/mobility impairment, and presence of feeding tube. However, potentially modifiable risk factors include witnessed aspiration events, use of sedating medication, and lack of oral care (63,64).

Identification of a causative pathogen in episodes of NHAP often is limited by access to diagnostics and quality of specimen collection. In a prospective cohort of patients >65 years presenting with either community acquired pneumonia (CAP) or NHAP, an etiology was identified in <30% of episodes despite >90% of subjects undergoing diagnostic testing (65). Similar to a previous study of LRTI in LTCF residents, this study showed respiratory viruses were the most commonly identified etiology in instances of NHAP (61,65). Data are mixed in the literature about the most common bacterial etiology of NHAP. Streptococcus pneumoniae was identified as the bacterial cause in 58% of episodes in one 10-year prospective study of 150 patients with NHAP, while gram-negative bacilli (e.g., Haemophilus influenza, Pseudomonas sp. Klebsiella sp.) were more common than S. pneumoniae in a cohort of 115 episodes (65,66). Neither study showed high prevalence of multidrugresistant organisms causing NHAP, but these episodes often were more severe. Although infrequently identified as a cause of NHAP in prospective studies, Legionella spp. have been reported in several outbreaks of pneumonia in LTCFs and should be considered as a cause of sporadic NHAP if there is evidence of Legionella colonizing the water distribution system of a facility (67).

A multifaceted approach should be taken to assess the risk of and implement strategies to prevent NHAP in LTCF residents. As outlined previously, identifying and addressing modifiable risk factors, such has improving oral hygiene, has been shown to be feasible and effective (68). A universal approach to LRTI prevention has been through promotion of both influenza and pneumococcal vaccination (69). Despite concerns about decreased vaccine efficacy in the aging population, the use of the influenza and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines has been shown to confer protection against invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumonia-related hospitalizations and mortality in nursing home residents (70,71

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree