T-Cell and Natural Killer–Cell Neoplasms With Primarily Leukemic Involvement

T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia

Overview and Incidence

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an aggressive, mature T-cell malignancy affecting predominantly older adults and accounts for 2% of chronic leukemias. There is an approximate 3:1 male predominance. Patients with ataxia telangiectasia show an increased incidence of T-PLL.

Etiology and Histopathology

The peripheral blood and bone marrow demonstrate a proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphocytes, with round to oval nuclei, mature chromatin, characteristic blebbing of the cytoplasm, and usually a prominent nucleolus, although in a minor subset of cases the nucleoli may not be visible (small cell variant) ( Fig. 13.1 ). , The bone marrow typically shows effacement with variable reticulin fibrosis. The liver, spleen, and lymph nodes can additionally be involved. The neoplastic cells are positive for most T-cell markers, including CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD7. The CD4 + /CD8 − immunophenotype is present in 60% of cases, the CD4 + /CD8 + in 25%, and the remaining 15% are CD4 − /CD8 + . CD52 is frequently expressed and is a targetable antigen.

A recurrent cytogenetic abnormality involving chromosome 14 can be detected in almost 75% of T-PLL cases, more commonly inv(14)(q11q32) and less commonly t(14;14)(q11q32), both of which juxtapose the TRA locus with the TCL1A and TCL1B oncogenes. This leads to overexpression of TCL1 , which can be detected by immunohistochemistry, aiding in the diagnosis. Mutations in genes involved in the JAK/STAT pathway are frequent ( JAK1, JAK3, STAT5B ).

Clinical Features

Patients are often asymptomatic but can present with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and circulating disease with associated cytopenias. Cutaneous involvement and pleural effusions can be seen on occasion. The clinical course is typically very aggressive, with poor response to conventional chemotherapy and median survival of 1 to 2 years. ,

Diagnostic Studies

Examination of the peripheral blood is a key diagnostic test, and flow cytometry (FC) is often helpful in establishing the immunophenotype. T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 1 (TCL1) oncoprotein overexpression and demonstration of inv(14)(q11q32) or t(14;14)(q11q32) can also be used to support the diagnosis.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

T-PLL does not have a formal staging scheme.

T-Cell Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia

Overview and Incidence

T-cell large granular lymphocytic (T-LGL) leukemia accounts for 2% to 6% of chronic lymphoproliferative disorders, characterized by a persistent increase in large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) that are clonal and not attributable to a secondary identifiable cause. It is a disease of older adults, with a median age of 60 years. ,

Etiology and Histopathology

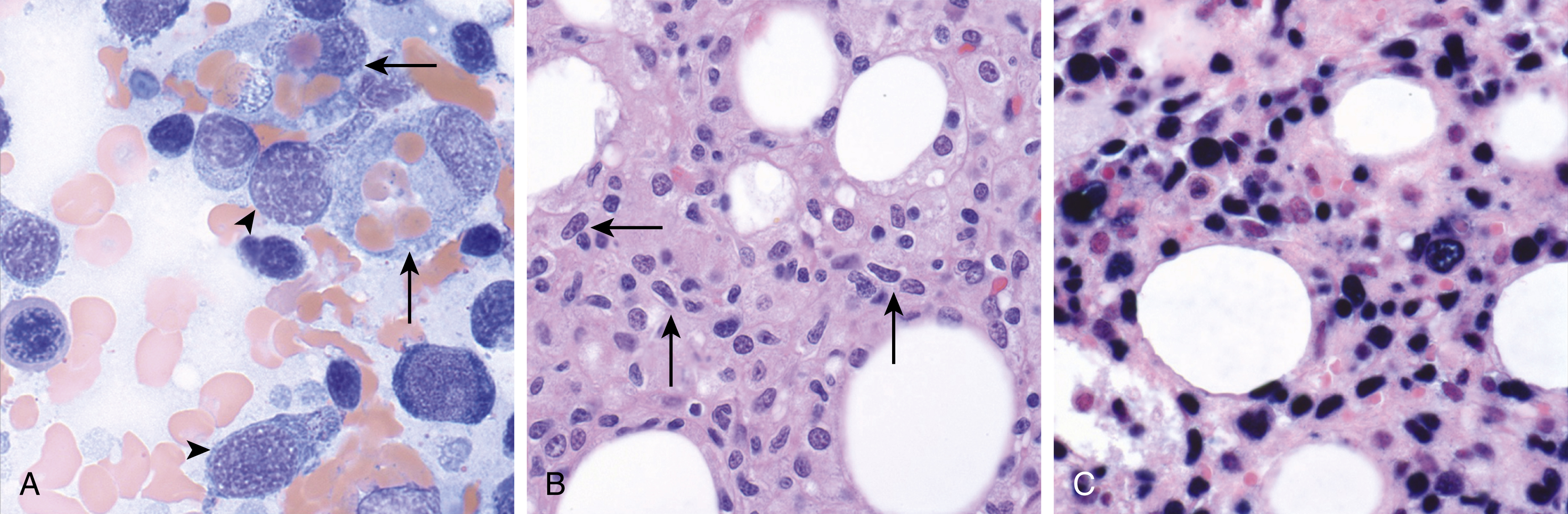

The pathogenesis of T-LGL leukemia is not entirely clear, although there is some thought that it may arise as the result of chronic antigenic stimulation, because it is associated with autoimmune diseases, in particular rheumatoid arthritis. T-LGL leukemia is characterized by increased circulating peripheral blood neoplastic LGLs (usually 2–20 ×10 9 /L), which show similar morphologic features as reactive LGLs (enlarged nuclei with mature chromatin, abundant pale cytoplasm, with azurophilic granules) ( Fig. 13.2 ). The bone marrow and spleen can also be involved classically in a sinusoidal pattern ( Fig. 13.2 ). T-LGL leukemia typically shows a cytotoxic T-cell immunophenotype, with expression of CD2, CD3, CD8, CD16, and CD57, and α-β T-cell receptor (TCR). Rarely, CD4 + or γ-δ TCR variants are seen. CD5 and CD7 partial or complete loss can be seen, and CD56 expression is uncommon. Although no recurrent cytogenetic abnormality has been identified, the majority of cases demonstrate activating mutations in STAT3 and a subset show activating mutations in STAT5B .

Clinical Course

T-LGL leukemia often presents with peripheral blood lymphocytosis and can cause splenomegaly, although a significant percentage of patients are asymptomatic, and their disease is discovered incidentally. Patients can present with neutropenia and associated bacterial infections. Patients who are asymptomatic and without significant disease-related cytopenias may not require treatment at diagnosis. The majority of cases show an indolent course, with 5-year survival noted at 89% according to a large French study.

Diagnostic Studies

Most frequently, T-LGL leukemia is diagnosed on a peripheral blood smear, showing persistent large granular lymphocytosis. FC and TCR clonality studies are often used to aid in the diagnosis. Some caveats: although technically a T-LGL count of less than 2 × 10 9 /L could be diagnosed according to current criteria as T-LGL leukemia (provided other parameters are met), it is controversial whether these cases truly represent a malignancy. Furthermore, it is important to bear in mind that clonal expansions of T-LGLs can be seen in the setting of bone marrow transplants or in association with other malignancies, and it is only when other causes are excluded that a diagnosis of T-LGL leukemia can confidently be made.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

No formal staging system is used for T-LGL leukemia.

Aggressive Natural Killer–Cell Leukemia

Overview and Incidence

Aggressive natural killer–cell leukemia (ANKL) is an exceptionally rare neoplasm of mature natural killer (NK) cells. The majority of cases have been reported in East Asia, Central America, and South America in young to middle-aged adults, with two peaks: one in the third and the other in the fifth decade of life. There is no definite sex predilection. ,

Etiology and Histopathology

The pathophysiology of this disease remains elusive; however, there is a strong association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), supportive of a critical role in its development. Morphologically, the peripheral blood and bone marrow (and often the liver and spleen) show involvement by an atypical mononuclear cell infiltrate, which can show variable morphology. Cells generally show a moderate amount of cytoplasm with sparse, variably prominent granules, and the nuclear features can range from mature (resembling large granular lymphocytes) to blastic (with some cases morphologically indistinct from acute myeloid leukemia) ( Fig. 13.3 ). Nucleoli are variably prominent. The degree of bone marrow involvement and burden of circulating disease are also highly variable. The bone marrow is typically involved in an interstitial pattern and can be associated with necrosis. There is a high association with hemophagocytosis, in which the macrophages may obscure the ANKL.

The neoplastic cells in ANKL are positive for CD2, CD3 (cytoplasmic, but not surface), CD56, T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), and EBER by in situ hybridization. CD5 is typically negative and CD16 is frequently positive. The morphology and immunophenotype can be similar to that of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (NKTCL), nasal type; however, NKTCL affects older patients and primarily the nasal cavity and nasopharynx and is typically CD16 negative. ,

Clinical Course

Patients typically present with systemic symptoms (fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss), hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and circulating disease. The clinical course is highly aggressive and is often complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, multiorgan failure, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Durable remissions are rare. There is no standard of care for treatment of this disease. Rarely, ANKL can evolve from a long-standing chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells and can be EBV − .

Diagnostic Studies

Examination of the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow is typically used for diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry (with EBER in situ hybridization) and FC can be quite useful in identifying subtle infiltrates.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

There is currently no formal clinical staging scheme for ANKL.

Chronic Lymphoproliferative Disorder of Natural Killer Cells

Overview and Incidence

Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells (CLPD-NKs) is defined as a sustained increased in peripheral blood mature NK cells of 2 × 10 9 /L or more for longer than 6 months without a clear cause (i.e., reactive etiologies must be excluded). This is a rare entity, which typically affects older adults (median age 60 years). There is no known sex predilection.

Etiology and Histopathology

Unlike many other NK cell disorders, CLPD-NKs is not associated with EBV. There is some speculation that NK cell activation via chronic infection plays a role, but this is not confirmed. The blood and bone marrow are involved by a population of large granular lymphocytes with enlarged nuclei, mature chromatin, moderate to abundant pale cytoplasm, and azurophilic granules ( Fig. 13.4 ). Although these features resemble T-LGL leukemia morphologically, the immunophenotype is that of a mature NK cell, with expression of cytoplasmic CD3, but not surface CD3, CD16, CD56 (often dim), CD2, TIA-1, and granzyme. CD2, CD5, CD7, and CD57 are often dim or absent. , Aggressive NK cell leukemia may also be in the differential diagnosis. However, CLPD-NK is not associated with EBV; the clinical features differ between these two entities. Clonality can be demonstrated by restricted expression of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs); however, in some cases of CLPD-NK, restricted KIR expression is absent. In recent years activating STAT3 and STAT5B mutations have been identified in this neoplasm.

Clinical Course

Many patients are asymptomatic and are incidentally diagnosed by an abnormal routine complete blood cell count (CBC). Others present with symptoms related to cytopenias. Hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy are rare. The natural history is indolent in most cases, with no treatment necessary, although transformation to an aggressive NK disorder can be seen.

Diagnostic Studies

An abnormal increase in circulating mature NK cells can generally be demonstrated through morphologic and immunophenotypic evaluation of the peripheral blood by FC. This finding, in the appropriate clinical setting, is diagnostic of CLPD-NKs. KIR studies can be pursued to establish clonality, which may be helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Of note, bone marrow involvement may be subtle, and staining for CD3 and TIA-1 prove helpful in identifying focal infiltrates.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

No formal staging system is used for CLPD-NKs.

Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma (ATLL)

Overview and Incidence

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is an uncommon mature helper T-cell malignancy causally linked to human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV)-1. As such, it is largely restricted to endemic HTLV-1 areas, including central Africa, southwestern Japan, Iran, and the Caribbean basin. Owing to a long latency period after infection, ATLL is a disease of adults.

Etiology and Histopathology

A postthymic helper T-cell infected with HTLV-1 expresses the viral protein p40 tax, which has various downstream cellular functions transcription of genes that mediate proliferation and resistance to apoptosis (including activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), Akt signaling, and cyclin-dependent kinases, and silence of p53 functions). In additional, the HTLV-1 basic leucine zipper factor (HBZ) is thought to play a role in maintenance of T-cell proliferation and oncogenesis after the initiating events.

ATLL is characterized by blood and bone marrow involvement by a population of atypical lymphocytes with morphology that can be quite variable ( Fig. 13.5 ). The neoplastic cells can range in size from small to large and can show blastic or mature chromatin. The prototypical ATLL cell is medium to large, shows mature chromatin, and a distinctive nuclear lobation, sometimes referred to as a “flower cell.” The neoplastic cells typically show a helper T-cell immunophenotype, with expression of CD4, although rarely CD4 − /CD8 + , CD4 + /CD8 + , and CD4 − /CD8 − variants have been described. CD2, CD3, and CD5 are typically retained, but loss of CD7 is common and associated with poor prognosis. , CD25 is strongly expressed in virtually all cases.

Clinical Course

ATLL can be subdivided into multiple forms: smoldering, chronic, lymphomatous, and acute (leukemic). The smoldering form is defined by more than 5% abnormal T-cell lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, in the setting of a normal lymphocyte count, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), calcium, and absence of lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and bone marrow infiltration. The chronic form is similar to the smoldering form except it can be associated with lymphocytosis, slightly increased LDH, and mild hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. The lymphomatous form presents with diffuse involvement of the lymph nodes. The acute (leukemic) form presents with constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss), as well as elevated LDH, hypercalcemia, and lytic bone lesions. Multiple organs may be involved, and hepatosplenomegaly and bone marrow infiltration are common. Of these, the lymphomatous and acute leukemic forms are typically aggressive, with a median overall survival of less than 1 year. By comparison, the chronic and smoldering forms have a more indolent clinical course, but they can also progress to a more aggressive form in a subset of patients.

Diagnostic Studies

A careful clinical history demonstrating HTLV-1 exposure or demonstration of positive HTLV-1 serology in conjunction with evaluation of the peripheral blood, bone marrow, and lymph nodes with ancillary testing (FC immunophenotyping, immunohistochemistry) can lead to the diagnosis of ATLL.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

There is no formal staging scheme for ATLL; however, the four clinical variants of ATLL (see previous section) can provide significant prognostic information.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas With Significant Leukemic Involvement

Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome

Overview and Incidence

Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) are variant presentations of a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. MF primarily involves the skin, whereas SS is defined by a triad of erythroderma, diffuse lymphadenopathy, and circulating disease. MF is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, affecting primarily adults and the elderly, and accounts for 50% of all cases of primary cutaneous lymphoma.

Etiology and Histopathology

The pathophysiology of MF/SS is not well understood, but there is some speculation that it may initially arise owing to persistent antigenic stimulation, possibly caused by infectious agents. Morphologically, MF skin lesions vary with the stage of disease. Early patch lesions show a superficial bandlike or lichenoid infiltrate, composed of small- to medium-sized atypical lymphocytes that classically show cerebriform nuclei and a perinuclear halo. Diagnosis of early MF can be quite challenging, and there is a morphologic overlap with inflammatory skin conditions. In the earliest premycotic stage, there is a mild lymphocytic infiltrate mainly in the upper epidermis without significant epidermotropism. Biopsy findings at this early stage may be nondiagnostic. Plaque-stage MF shows a denser dermal infiltrate, with a greater degree of epidermotropism and occasionally a well-defined collection of atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis (Pautrier microabscesses). Tumor-stage MF is often more florid, showing nodular infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes, which often show greater size and shape variability. Large cell transformation, defined as more than 25% of the infiltrate, can also be seen. MF variants, including pagetoid reticulosis (marked intraepidermal component), folliculotropic MF (infiltration of hair follicles, with sparing of epidermis), syringotropic MF (infiltration of eccrine ducts and glands), granulomatous slack skin (granulomatous dermal infiltrate containing atypical T-cells admixed with macrophages and multinucleated giant cells), and hypopigmented/hyperpigmented MF, each with distinct clinicopathologic findings, also exist. Folliculotropic and syringotropic MF often co-occur.

SS can be preceded by MF (and should be termed secondary SS) or can present de novo. In SS, the peripheral blood shows atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei ( Fig. 13.6 ). The histopathology of erythrodermic skin biopsy specimens shows a range of findings, including nonspecific histologic appearances more in line with chronic dermatitis, as well as a dermal bandlike infiltrate with atypical lymphocytes, similar to MF. Lymph nodes show partial or total effacement by a monotonous population of lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei. Other organs, including the liver, lungs, spleen, central nervous system, and so on, can be involved, although the bone marrow is often spared.

The lymphomatous cells in both MF and SS are almost always of T-helper cell lineage with expression of CD4, although rare CD4 − /CD8 + , CD4 + /CD8 + , or CD4 − /CD8 − variants are seen. Classically CD7 and CD26 are lost, and there can be dim expression of CD2, CD3, CD4, and/or CD5. Clonal TCR rearrangements can be detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or high-throughput sequencing, and FC can also be used to assess the V region on the β chain (Vβ analysis) to establish clonality. CD30 expression is variable and can often be seen in the setting of large cell transformation.

Clinical Course

In the premycotic period, MF presents with nonspecific skin lesions that can wax and wane over years and never progress. If there is to be progression, it typically occurs in a stepwise fashion from patch to plaque to tumor stage. Most lesions are on the trunk, but lesions can arise anywhere on the body. SS, on the other hand, presents with diffuse lymphadenopathy, intensely pruritic diffusely erythrodermic skin, and lymphocytosis. MF shows an indolent clinical course overall; however, prognosis is highly dependent on stage. SS is characterized by an aggressive clinical course, with median survival of less than 2.5 years. ,

Diagnostic Studies

A careful clinical examination in conjunction with a skin biopsy is required for diagnosis of MF. Immunohistochemical stains, FC, and assessment for T-cell clonality can aid in the diagnosis. SS is often diagnosed through morphologic and flow cytometric evaluation of the peripheral blood. Furthermore, demonstration of an identical clone in the peripheral blood as the skin can also help establish a diagnosis of SS.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

In 2007, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) recommended revisions to the original Mycosis Fungoides Cooperative Group (MFCG) staging system to reflect advances in our understanding of MF/SS. The ISCL/EORTC staging system is shown in Table 13.1 .

| TNM Stages | Description |

|---|---|

| Skin | |

| T1 | Limited patches, papules, or plaques covering <10% of skin surface |

| T2 | Patches, papules, or plaques covering ≥10% of skin surface |

| T3 | One or more tumors (≥1 cm diameter) |

| T4 | Confluence of erythema covering ≥80% of skin surface |

| Lymph Nodes | |

| N0 | No clinically abnormal peripheral lymph nodes; biopsy not required |

| N1 | Clinically abnormal lymph nodes, histopathology Dutch grade 1 or NCI LN 0–2 |

| N1a | Nonclonal TCR rearrangement |

| N1b | Clonal TCR rearrangement |

| N2 | Clinically abnormal lymph nodes, histopathology Dutch grade 2 or NCI LN 3 |

| N2a | Nonclonal TCR rearrangement |

| N2b | Clonal TCR rearrangement |

| N3 | Clinically abnormal lymph nodes, histopathology Dutch grade 3–4 or NCI LN 4 , clonal or nonclonal TCR rearrangement |

| Nx | Clinically abnormal lymph nodes, no histologic confirmation |

| Visceral | |

| M0 | No visceral organ involvement |

| M1 | Visceral organ involvement (must have pathologic confirmation, except spleen and liver, which may be diagnosed by imaging criteria) |

| Blood | |

| B0 | ≤5% of peripheral blood lymphocytes are Sézary cells |

| B0a | Nonclonal TCR rearrangement |

| B0b | Clonal TCR rearrangement |

| B1 | >5% of peripheral blood lymphocytes are Sézary cells |

| B1a | Nonclonal TCR rearrangement |

| B1b | Clonal TCR rearrangement |

| B2 | ≥1000/μL Sézary cells, clonal TCR rearrangement |

Predominantly Extranodal (Noncutaneous) With Significant Leukemic Involvement

Hepatosplenic T-Cell Lymphoma

Overview and Incidence

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTL) is a rare aggressive subtype of T-cell lymphoma that involves not only the liver and spleen, but also frequently involves the bone marrow, resulting in cytopenias and, on occasion, circulating disease. It is quite rare, accounting for 1% to 2% of all peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), with peak incidence occurring in adolescents and young adults with a slight male predominance. , ,

Etiology and Histopathology

Up to 20% of HTSLs arise in the setting of chronic immunosuppression, including in the setting of solid organ transplants (in which case, classification should be as a posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, HSTL-type) as well as treatment for autoimmune disease (e.g., Crohn disease).

Morphologically, HSTLs demonstrate a sinusoidal pattern of infiltration in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow ( Fig. 13.7 ). The lymphomatous cells are characterized by small- to medium-sized nuclei with coarse chromatin and a moderate amount of pale cytoplasm ( Fig. 13.7 ). These lymphomas typically show a γ’δ T-cell immunophenotype and are CD2 + , CD3 + , CD5 − , CD7 + / − , CD4 − , CD8 − , CD56 + , and CD57 + / − . Activation antigens CD25 and CD30 are usually negative. Granzyme B and perforin are typically negative, and TIA-1 is almost always positive. , , , T-cell γ-receptor genes are rearranged in most cases, and isochromosome 7q has been identified in most cases studied. ,

Clinical Features

Patients classically present with hepatosplenomegaly and cytopenias (marked thrombocytopenia, and often anemia and leukopenia), as well as systemic symptoms, including fever, fatigue, and weight loss. Lymphadenopathy is virtually always absent. The prognosis is typically poor. Although most patients initially respond to chemotherapy, relapses are common and the median survival is less than 2 years.

Diagnostic Studies

Liver or spleen and bone marrow biopsy are typically used in the diagnosis of HSTL. Ancillary testing, including FC, and molecular studies (PCR for clonal T-cell receptor rearrangements) can aid in the diagnosis.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

Staging for HSTL is currently performed according to the Ann Arbor staging system ( Table 13.2 ).

| Principal Stages | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Involvement of 1 lymph node region only |

| Stage II | Involvement of ≥2 lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm |

| Stage IV | Diffuse or disseminated disease involving one or more extralymphatic organs or tissues, with or without lymph node involvement a |

| Systemic symptoms | Fever, drenching night sweats, or weight loss (at least 10% over the past 6 months) |

| A | Absent |

| B | Present |

| E | Extranodal involvement by direct extension |

| X | Bulky disease (largest deposit >10 cm), or mediastinum is wider than 1/3 of the chest on imaging |

a D + , skin and subcutaneous tissue; H + , liver; L + , lung; M + , marrow; O + , bone; P + , pleura.

Systemic EBV + T-Cell Lymphoma of Childhood

Overview and Incidence

Systemic EBV + T-cell lymphoma (TCL), no longer referred to as a “lymphoproliferative disorder” of childhood, is a rare but aggressive disease, characterized by a clonal proliferation of EBV-infected T cells. It is most prevalent in Asia, especially in Japan and Taiwan. There is no sex predilection.

Etiology and Histopathology

The etiology of systemic EBV + TCL of childhood is unknown, but it typically occurs shortly after acute EBV infection or in the setting of chronic active EBV (CAEBV). The association with EBV and racial predilection suggests a genetic defective immune response to EBV.

Morphologically, there is an infiltrating T-cell proliferation that most commonly involves the liver and spleen, followed by the lymph nodes and bone marrow. The lesional cells may be small and lack significant cytologic atypia; in other instances, pleomorphism may be seen ( Fig. 13.8 ). The liver and spleen show a sinusoidal pattern of infiltration with marked hemophagocytosis. , ,

The neoplastic cells show an activated cytotoxic immunophenotype, with expression of CD2, CD3, and TIA-1. CD56 is typically negative. Cases that arise after an acute EBV infection are generally CD8 + , whereas those that arise in the setting of CAEBV are typically CD4 + . An EBER in situ hybridization stain is positive in the lymphomatous cells. A clonal TCR rearrangement is demonstrable in the vast majority of cases.

Clinical Course

Patients present with acute onset of fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and occasionally lymphadenopathy. Liver failure, pancytopenia, and hemophagocytic syndrome with multiorgan failure may follow. The prognosis is poor; most patients have a fulminant clinical course leading to death usually within days to weeks.

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnosis relies heavily on characteristic clinical and laboratory findings (including EBV serology, EBV PCR) in the setting of a tissue biopsy confirming the presence of the neoplastic EBV-infected T-cells. Demonstration of a clonal TCR may also aid in the diagnosis.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

There is currently no formal staging system for systemic EBV + TCL of childhood.

Chronic Active EBV Infection of T- and NK-Cell Type, Systemic Form

Overview and Incidence

Systemic CAEBV of T- and NK-cell type shows a strong racial predisposition, affecting Asian populations primarily, including Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China. There is no sex predilection. ,

Etiology and Histopathology

Although the pathogenesis of this disease remains unclear, the association with EBV and racial predilection suggests a genetically linked defective immune response against EBV. This is further evidenced by the observation that EBV-specific cytotoxic T-cell activity is frequently impaired in patients with CAEBV. The liver and spleen show involvement by a population of cells that do not show morphologic changes suggestive of a neoplastic proliferation. The liver shows sinusoidal and portal infiltrates suggestive of viral hepatitis, whereas the spleen shows congestion of the red pulp with atrophy of the white pulp. The lymph nodes show variable morphology, including paracortical and follicular hyperplasia, focal necrosis, and epithelioid granulomas. The immunophenotype of the EBV-infected cells is variable. They can show a T-cell or NK-cell phenotype. Progression to NK/T-cell lymphoma or aggressive NK-cell leukemia occurs in a subset of cases. Systemic CAEBV can be polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal. Cases of systemic CAEBV with monoclonality can be challenging to distinguish from EBV + T-cell lymphoma of childhood. ,

Clinical Course

In general, patients present with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, persistent hepatitis, lymphadenopathy, and variable skin findings. The clinical severity is dependent on the viral load and immune response. Patients with T-cell CAEBV often present with more prominent systemic symptoms, including fever, high titers of EBV antibodies (antiviral capsid antigen and anti-early antigen immunoglobulin [Ig] G) and high levels of circulating EBV DNA. In contrast, patients with NK-cell CAEBV show milder systemic symptoms, often have skin findings (rash/severe mosquito bite allergy), and high levels of IgE. Hemophagocytic syndrome is seen in a subset of cases (24%). Other complications are quite varied and include coronary artery aneurysm, myocarditis, hepatic failure, interstitial pneumonia, central nervous system (CNS) involvement, and gastrointestinal (GI) perforation. , ,

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnosis of systemic CAEBV of T- and NK-cell type is heavily reliant on the clinical presentation and laboratory findings (EBV serology, EBV DNA viral load). Tissue biopsy of the liver and/or spleen may confirm the presence of infiltrating T- or NK-cells, further supporting the diagnosis.

Current Clinical and Radiologic Staging

No formal staging system exists for systemic CAEBV.

Nodal-Based T-Cell Lymphomas

Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified

Overview and Incidence

The PTCL, not otherwise specified (NOS) category represents not a single disease, but a heterogeneous group of TCLs that do not fit well into other specifically defined entities. As such, these tumors account for approximately 30% of mature TCLs. PTCL, NOS typically occurs in middle-aged or older adults and is quite rare in the pediatric population.

Etiology and Histopathology

Morphologically, involved lymph nodes are diffusely effaced or show paracortical expansion if architecture is retained. A wide range of cytologic appearances can be seen; the cells can be small, medium, or large, and the infiltrate can be monomorphic or pleomorphic. There is often an associated mixed inflammatory background composed of small lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and large B cells. , , Overt peripheral blood involvement is rare ( Fig. 13.9 ), but the bone marrow is frequently involved and can show a range of infiltrative patterns.