- The diabetes epidemic is not sparing hospital practice. Approximately 12–24% of all hospital inpatients have diabetes.

- A significant proportion of hospital inpatients with hyperglycemia have undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia.

- Hospitalization frequently presents a missed opportunity to diagnose diabetes and to identify those at risk for diabetes.

- In-hospital hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia are associated with poor outcomes in a broad range of specialties.

- There are few randomized controlled trials demonstrating benefit from interventions in the inpatient care setting.

- Hospital inpatients with diabetes frequently have multiple co-morbidities and complex medical and nursing requirements.

- Ward-based staff are frequently poorly trained and therefore ill-equipped to manage diabetes care safely and effectively.

- Care of the critically ill patient with diabetes and hyperglycemia requires highly skilled and appropriately trained staff.

- Insulin and diabetes management errors continue to compromise patient safety.

- Structured diabetes care delivered by appropriately trained staff and supported by a dedicated specialist inpatient team in partnership with the patient improves the patient experience, reduces diabetes prescribing and management errors and length of stay in many clinical settings in hospital.

- Patients with diabetes are more likely to undergo in-hospital procedures and should be individually managed by agreed and audited protocols.

- Patients undergoing surgery should have a preoperative assessment, a robust risk assessment and an individualized care plan including a safe and effective discharge plan.

- Standards of care for hospital inpatients have been defined by professional organizations but are not globally implemented.

- Audit of inpatient care reveals poor standards of care and patient experience and demonstrates the inadequacy of present systems and processes.

Introduction

Known diabetes in hospital

The global burden of diagnosed diabetes has reached epidemic proportions. The International Diabetes Federation predicts that by the year 2030 prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes will have increased by approximately 20% in Europe and by 65–98% in less economically developed countries [1]. Disproportionate numbers of people admitted to hospital have diabetes. The prevalence of diabetes in the inpatient population is almost certainly underestimated because of poor coding of diabetes as a co-morbidity. This applies equally to both planned and emergency care. Conservative estimates of diagnosed diabetes are between 12% and 24% of all inpatients in the USA [2]. Every year people with diabetes spend approximately 1.34 million days in hospital and it is estimated that in the UK there are 80 000 excess bed days per year. The cost of caring for inpatients with diabetes is around £485 million per year [3].

Undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia in hospital

The number of hospital inpatients with diabetes has increased and is rising inexorably. This only represents the tip of the iceberg, however, as it takes no account of those patients with a raised plasma glucose level without a diagnosis of diabetes. In addition to those with diagnosed diabetes, there are two other groups of patients with hyperglycemia in hospital. First, there are those with unrecognized diabetes occurring during hospitalization and subsequently confirmed after discharge and, secondly, those with so-called “hospital-related” hyperglycemia (fasting plasma glucose >126mg/dL (7mmol/L) or random >198mg/dL (11 mmol/L), occurring during hospitalization, which reverts to normal after discharge (also known as “stress hyperglycemia”). Recent studies suggest that these two groups may add a further 30% to the total numbers with raised plasma glucose levels [4]. So when the burden of “in-hospital hyperglycemia” is considered to include all three groups, then the prevalence is approximately 40% of all hospital inpatients.

Evidence of harm from in-hospital hyperglycemia and benefit of glucose lowering

There is compelling evidence that poorly controlled blood glucose levels are associated with a higher in-hospital morbidity and mortality, prolonged length of stay, unfavorable post-discharge outcomes and significant excess health care costs [5–9]. Umpierrez et al. [4] showed that patients with new hyperglycemia had an 18-fold increased in-hospital mortality and patients with known diabetes had a 2.7-fold increased in-hospital mortality when compared with normoglycemic patients [4]. In 2004, a joint position statement from the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control concluded that hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is a common, serious and costly health care problem [10]. There was a strong recommendation for early detection of hyperglycemia and an aggressive management approach to improve outcomes.

Randomized trials have demonstrated improved outcomes resulting from more aggressive management of hyperglycemia in the following areas.

Acute coronary syndromes

It is not clear whether high glucose is a marker or mediator of poor outcomes in acute coronary syndromes (ACS). In the management of myocardial infarction a meta-analysis of 15 studies showed that blood glucose (BG) >120mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L), with or without a prior diagnosis of diabetes, was associated with an increased in-hospital mortality and subsequent heart failure [11]. Current evidence supports the use of intravenous insulin in the first 24 hours and intensified subcutaneous insulin for 3 months in the setting of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) where the DIGAMI 1 study showed a 29% reduction in mortality at 1 year [12]. Other randomized controlled trials such as DIGAMI-2 and CREATE-ECLAT have failed to reproduce these findings [13,14].

Observational data from the UK Myocardial Infarction National Audit Programme (MINAP) of patients with troponinpositive ACS demonstrated poorer outcomes in those with an elevated BG on admission, with 30-day mortality of 20.2% in those with BG >170mg/dL (9.4mmol/L) compared with 3.3% in those with BG <170mg/dL (9.4mmol/L). Of 38864 patients recorded on the MINAP database, around 10% (of those with no prior diagnosis of diabetes) had an admission BG > 250 mg/dL (14 mmol/L). Patients who did not receive treatment with intravenous insulin had a relative increased risk of death of 56% at 7 days and 51% at 30 days [15].

Cardiac surgery

Most of the outcome data for patients undergoing cardiac surgery relates to the Portland Diabetic Project, which was a non-randomized observational study of 5510 patients undergoing cardiac surgery during 1987–2005. This has shown that patients with hyperglycemia managed with an intravenous infusion titrated to normoglycemia for 3 days postoperatively had improved mortality, reduction in deep sternal wound infections and reduction in length of stay [16].

Critical care setting

The landmark study by Van den Berge et al. [17] showed that postoperative intensive insulin therapy (IIT) reduced mortality and morbidity in patients in the surgical intensive treatment unit (ITU). In a later study by the same group in medical ITU patients, IIT reduced morbidity but not mortality [18]. Randomized trials of IIT have shown inconsistent effects on mortality and increased rates of severe hypoglycemia. A recent meta-analysis of 26 trials involving 13 567 patients including the recent NICE-SUGAR trial, the pooled relative risk of death with IIT compared with conventional therapy was 0.93 (95% CI 0.83–1.04). Fourteen trials reported hypoglycemic events and showed a significant increase in severe hypoglycemia with a relative rate (RR) of 6.0 (95% CI 4.5–8.0). The different targets of IIT did not influence either mortality or risk of hypoglycemia [19].

Pathophysiology of hyperglycemia in acute illness

A key goal of inpatient diabetes management is minimizing the metabolic decompensation from the stress of illness and surgery. Stress-induced hyperglycemia is caused by the combined effects of integrated endogenous hormonal, cytokines and counter-regulatory nervous system signals on glucose metabolic pathways [20]. Inflammatory and counter-regulatory responses to critical illness alter the effect of insulin on hepatic glucose production and skeletal muscle. Stress leads to the increased secretion of counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon, epinephrine, norepinephrine, cortisol and growth hormone), which stimulates hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Peripheral uptake of glucose is inhibited. A major consequence of severe hyperglycemia is osmotic diuresis accompanied by dehydration and electrolyte disturbances (sodium, potassium, magnesium and phosphate). This increased osmotic state is procoagulant.

The stress hormones also accelerate fat and protein breakdown leading to a generalized catabolic state. In the surgical setting, starvation preoperatively and postoperatively can be a large contributor to this process. In people without diabetes, a compensatory increase in insulin secretion helps to mediate against these catabolic effects. Patients with an absolute insulin deficiency are prone to unopposed lipolysis and ketone body formation that can ultimately result in diabetic ketoacidosis.

Stress increases the release of inflammatory mediators, leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia [21]. Inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-α) may directly or indirectly enhance both hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. TNF-α alters the signaling properties of insulin receptor substrate, leading to enhanced target organ insulin resistance.

Wound healing and the susceptibility to infection are also affected by hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency, as demonstrated by in vitro studies looking at white blood cell functioning [22]. Hyperglycemia-induced abnormalities in the phagocytic and bactericidal actions of neutrophils are reversed with improved glucose control.

There are other causes of hyperglycemia, which may be more specifically related to the hospital admission [23]. These include co-administered medications such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants (e.g. cyclosporine, tacrolimus). Immobility secondary to surgery, trauma or acute illness can accelerate both hyperglycemic and procoagulant states.

Effects of glucose lowering and intravenous insulin therapy

The mechanisms behind the improved outcomes from intravenous insulin are numerous. The vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects of insulin have been studied. In vitro, insulin induces a dose-dependent increase in nitrous oxide synthase production in the endothelium. Ultimately, insulin treatment may improve endothelial function in patients with diabetes [24].

Current recommended standards of care for hospital inpatients with diabetes

Several professional organizations from different countries have published suggested standards of care for hospital inpatients. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) is an umbrella organization of over 200 national diabetes associations in over 160 countries which has also published a standards document about inpatient care in type 2 diabetes. The content of the major publications are reviewed below. There are a number of recurring themes which include equitable access to specialist services, empowerment of patients, delivery of care by agreed guidelines, setting of glycemic targets and embedding effective and audited hyperglycemic management protocols.

International Diabetes Federation 2005

Within the guideline produced by the IDF on the care of patients with type 2 diabetes, a number of recommendations were made concerning inpatient care [25]. The standard recommendation of the IDF group fell broadly into four categories:

American Diabetes Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2006

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Technical Review on the Management of Diabetes and Hyperglycemia in Hospital was published as an in-depth review of the literature on this topic and outlined practical management strategies [26]. The implementation of these policies and recommendations had remained an elusive goal in everyday clinical practice. Therefore, in 2006, the ADA and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) produced a further consensus statement entitled Inpatient Diabetes and Glycemic Control: A call to action in an attempt to identify and overcome barriers to change in practice to facilitate improvement in inpatient diabetes care [27]. This was updated in 2009 with new glycemic targets based on recent publications that have demonstrated concern about the harmful effect of in-hospital hypoglycemia in some clinical settings [28].

Canadian Diabetes Association

The Canadian guidelines include separate sections on peri-operative and peri-acute coronary syndrome glycemic control, recommending glucose levels of 6.1 mmol/L in post surgical ITU patients and 128–180mg/dL (7.1–10mmol/L) in peri-myocardial infarction patients [29].

UK Diabetes Services

National Service Framework for Diabetes 2004

The Diabetes National Service Framework set out the first set of national standards for the treatment of diabetes [30]. Two standards were set for hospital care.

National Diabetes Support Group (NHS Diabetes) 2008

In 2008, the National Diabetes Support Group produced a document focusing on improvement of diabetes inpatient services and the commissioning of these services [31]. NHS Diabetes has now updated the commissioning toolkit to include the commissioning of emergency and inpatient care [31].

Diabetes UK 2009

Diabetes UK has produced a document for patients entitled “What care to expect in hospital”, available from Diabetes UK [32]. It is hoped that this empowerment of patients will help to drive up in-hospital standards of care. Diabetes UK in partnership with NHS Diabetes and a number of other professional bodies through the “Putting Feet First’ campaign have recently promoted the dissemination of a national guideline for the management of patients with acute diabetic foot problems in hospital.

National Health Institute of Innovation and Implementation 2009

The National Health Institute of Innovation and Implementation recently launched a package of recommendations to improve standards of care in hospital inpatients. This was branded the “Think Glucose” campaign and has been cascaded to all UK hospitals. Each acute hospital in the UK has been provided with a set of recommendations and a toolkit to drive improvement in standards [33].

Aims of diabetes inpatient care

Diabetes care in hospital inpatients poses a real challenge as most patients are admitted to a hospital bed with a condition unrelated to their diabetes, be that electively or as an emergency. Non-diabetes specialists are often in charge of their care, and they may often have little understanding of diabetes management and its importance on patient outcomes. As a result, there can be an increased risk of harm from issues such as lack of insulin dose adjustment or prescribing errors.

Achieving a good outcome

Patients should come to no harm because of their diabetes management. Hypoglycemia and excessive hyperglycemia are both are associated with poorer clinical outcomes and should be managed according to local protocols. Clinical guidelines supported by the use of integrated care pathways should be in place to drive up standards of care. Management by a specialist team with agreed protocols against agreed standards improves care for those admitted to hospital [34].

Supporting a rapid recovery

Patients with diabetes are twice as likely to be admitted to hospital and stay twice as long in a hospital bed [35]. Minimizing excess length of stay should be one of the principal aims of good inpatient care. Prolonged length of stay occurs for a multiplicity of reasons but is often because of diabetes mismanagement secondary to poor staff knowledge and lack of education. There is evidence that involvement of the specialist diabetes team, and in particular diabetes inpatient specialist nurses (DISNs), significantly reduces length of stay and insulin errors and improves the patient experience [36–38]. This requires a culture that invests in excellent communication between the person with diabetes, diabetes specialists and non-specialist teams to activate timely intervention by avoiding glycemic deterioration during hospital stay.

Facilitating a good patient experience and patients expressed concerns about inpatient care

Patients are accustomed to managing their own diabetes. Traditionally, patients are disempowered in the management of their diabetes as soon as they are admitted to a hospital bed. For those people with diabetes accustomed to self-management by insulin adjustment this is a negative experience [35]. The ADA [28] and Diabetes UK [32], while acknowledging the importance of diabetes self-management, highlighted the need to educate people with diabetes to deliver safe self-care in the hospital setting. Individuals suitable for self-management in hospital must be competent adults with a stable level of consciousness who successfully manage their diabetes at home. In addition, while in hospital it is advised that these patients have the physical skills appropriate to self-administer insulin; be accustomed to performing self-monitoring of blood glucose; and have adequate oral intake. In the event that self-care is deemed unsafe or impossible (e.g. critically ill, post surgery or unwilling), then there must be a governance arrangement to assess patient competency and if necessary supersede patients’ right to self-care.

Encouraging and supporting patients to have as much responsibility for their diabetes management as they wish for, and their clinical status allows, is likely to enhance the patient experience during a hospital stay. The Diabetes UK position statement on what care adults with diabetes should expect in hospital clearly focuses on the importance of patient self-management, while reminding health care professionals of the importance of policies and strategies being in place to support this concept in the ward setting (Table 32.1).

Table 32.1 Patients’ experiences of in-hospital diabetes care [60].

| 1 Experiences of disempowerment and distress. Patients felt that they were not engaged as partners in their care during their admissions, and in some cases patronized by staff members |

| 2 Food/food timings and their coordination with medication. This often refl ected a lack of understanding amongst staff of the relationship between food and good diabetes management |

| 3 Medicines mismanagement in hospital. People were given the wrong medication or dose |

| 4 Lack of communication between different multidisciplinary team members and with the person with diabetes. This led to basic failures in communication such as notifi cation of both changes in timings of procedures and dosages of medications to the patient |

| 5 Lack of hospital staff knowledge of diabetes management both in terms of basic care and respecting patient autonomy |

| 6 Importance of people with diabetes being allowed to self-manage and thereby respecting the role of the person with diabetes in usually self-managing their condition on a daily basis |

| 7 Positive experiences of good diabetes management and proactively allowing patients to self-manage |

Barriers to safe and effective diabetes care delivery in hospital

Systems failures

It is essential that the patient with diabetes is identified and flagged at an early stage of the admission process. The ADA recommends that all patients admitted to hospital should be identified in the medical record as having diabetes. The UK NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement also recommends a diabetes identifier as a prerequisite for ensuring quality of care [33]. Yet this has not been achievable in the UK in secondary care because of systems failure as a result of poor coding and inadequate information systems technology. In addition, if we are to identify those patients with undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia and make an impact on their poor outcomes there needs to be a policy of routine blood glucose screening for all hospital inpatients. This is not standard practice in the UK.

Ward environment factors

Basic diabetes care is often not well delivered in hospital. An analysis of 44 US hospitals revealed persistent shortcomings in diabetes management, including persistent excessive hyperglycemia [39]. The hospital environment is one that is characterized by instability and unpredictability for the patient. It is a major contributor to the difficulty of managing inpatient diabetes well. Intercurrent illness, in-hospital changes to a patient’s usual outpatient regimen, and the scheduling and unpredictability of tests and procedures contribute to glycemic instability [40]. A patient’s dietary intake may also be erratic, because of poor appetite, palatability of food or timeliness of delivery.

Staff training challenges

In the UK, qualified staff numbers have been reduced to a minimum and ward staff have little or no protected time for education and training other than mandatory training (fire, manual handling, back care, infection control) defined by the employing organization. Despite the large numbers of patients with diabetes in hospital, the only mandatory training in diabetes is in blood glucose monitoring. People with diabetes, who generally have a high level of knowledge about their condition, are therefore often being managed by nursing and medical staff with only a rudimentary training in diabetes care [41].

Insulin prescribing and delivery errors

Insulin treatment in hospital can be life-saving. It also has the potential to be life-threatening given its narrow therapeutic index. The prescribing of insulin is a minefield of ignorance and error. Insulin has been identified as one of the top five high-risk medications in the inpatient environment [42,43]. There is a wealth of material, predominantly from the USA and the UK, describing both medical errors and adverse events in the general inpatient population (Box 32.1). Medical errors, including those related to insulin treatment, are described as common in hospitals worldwide [44,45]. Insulin medication errors can occur at any stage in the process of prescribing, preparing and delivering the medication to the patient [46]. The potential consequences of error can be catastrophic. One-third of all inpatient medical errors that cause death within 48 hours of the error involve insulin administration [47].

Medical prescribing

A common recommendation emerging in both diabetes management and prescribing errors has been the need for appropriate medical staff education in diabetes and insulin treatment. Hellman [47] suggests that endocrinologists take on this role and maintain that junior doctors should be taught the principles of drug dosage and prescription writing before starting their ward placements. A report from the National Patient Safety Agency 2007 [49] devotes one entire page to insulin errors and advocates changes to pre-registration training to incorporate the principles and therapeutics of safe prescribing. The curriculum for junior doctors has been revised in recent years and new models of education have been implemented yet this has not reduced insulin prescribing errors in junior hospital doctors and therefore the process merits review.

Non-medical prescribing

In the UK, legislation for nurse prescribing, now known as non-medical prescribing, was implemented in 2003. The editorial by Aronson et al. [50] compared medical student training (approximately 61 hours) to that of nurse prescribers (162 hours of theory and 90 hours in practice). The authors called for the adoption of the British Pharmacological Society’s prescribing and assessment processes to be applied for doctors in training in the teaching of diabetes and insulin treatment. Aronson also called for the formation of an independent systematic review of medical prescribing and teaching by a multi-organizational body in order to inform practice. This process has yet to be implemented but if introduced could form the basis for training in diabetes medicines management.

Delivering effective diabetes care: the role of diabetes inpatient team

Diabetes inpatient teams are multidisciplinary; the health care professionals involved individually contribute specialist skills and together provide a holistic approach to patient care. As well as operating as a discreet unit, the team works closely with other medical specialities including the specialist diabetic foot team. The defined roles forming the diabetes specialist inpatient team include the following.

The Patient

Central to the diabetes team is the patient. The majority of people living with diabetes have developed highly competent and individualized management skills, therefore it is essential, where possible, that the patient is encouraged to participate in the formulation and conduct of their own care plan while in the ward setting.

Consultant physician

The primary role of the consultant physician is as leader of the multidisciplinary team. The consultant physician has ultimate responsibility for the clinical care of diabetes inpatients. They work closely to provide clinical support to diabetes specialist nurses (DSNs) and certified diabetes educators (CDEs), while being heavily involved in the training and education of other diabetes and non-diabetes health care professionals. With the need to maintain standards of care and update clinical guidelines, physicians are also frequently involved in audit and research work in order to ensure the highest quality of diabetes care for inpatients with diabetes.

Certified Diabetes Educator

In 2009, the Association of Diabetes Educators published a position statement, which emphasized the key role of CDEs in patient and staff education, the promotion and implementation of glycemic control strategies and appropriate nutritional therapies. In close partnership with social work, case managers and home care coordinators, they are able to facilitate a smooth patient pathway from hospital to home at discharge.

Diabetes specialist nurse

The work of DSNs is exclusively in diabetes care. In 2009, there were 1361 DSNs in the UK working in primary and/or secondary care settings. DSNs deliver patient-centered care wherever required and influence care delivery at every stage of the patient journey, including inpatient care. The role of the DISN has evolved in recent times and specifically focuses on supporting inpatients and the ward staff caring for them. Aside from clinical care, DISNs are frequently involved in medical and nursing education and also in guideline production and update. Not only can DISNs significantly reduce inpatient length of stay [36,37]. but if they also obtain non-medical prescribing skills, have also been seen to reduce insulin and diabetes management errors significantly [38].

Diabetes specialist dietitian

Diabetes specialist dietitians have a pivotal role in the care of diabetic inpatients with complex nutritional needs, in particular those patients who are unable to swallow or those required to adhere to a complex dietary regimen as in renal failure, cystic fibrosis and the elderly.

Other team members may include ward-based diabetes link nurses and diabetes specialist pharmacists.

Which type of patient needs to be seen by the diabetes specialist team?

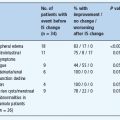

The correct answer to this question is that all patients with diabetes should have access to specialist diabetes services; however, given that up to 20% of all inpatients now have diabetes then in real world it is going to be almost impossible for specialist team members to see every patient. Specialist teams therefore, driven by need, have drawn up a priority list for which patients should be referred for assessment. An example of one of these referral criteria documents from Leicester, UK, is seen in Table 32.2.

Table 32.2 Indications for referral to diabetes inpatient specialist nurses (DISN). Adapted from University of Leicester Hospitals, UK.

| Always refer | Hyperglycemic emergencies (e.g. DKA, HHS) Acute coronary syndromes Severe or repeated hypoglycemia New diagnosis of diabetes Problems with intravenous insulin infusion or duration >48 hours Active foot ulceration Reduced consciousness Enteral or parenteral nutrition Vomiting and sepsis Patient request Persisitent hyperglycemia Pregnancy |

| Consider refer | Educational needs Stress hyperglycemia NBM >24 hours Poor wound healing |

| Rarely refer | Minor hypoglycemia Routine dietetic advice Simple educational needs Well-controlled and managed diabetes |

DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; HSS, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome; NBM, nil by mouth.

Management of in-hospital hyperglycemia

All hospitals should have a policy for glycemic management and or blood glucose monitoring in place according to the ADA [28] or the National Institute for Health, Innovation and Improvement (NHSIII) standards of care. The newly introduced UK “Think Glucose” campaign from the NHSIII has as its mantra, “It is as unacceptable for hospitals not to have a glycemic management policy as it is for them not to have an infection control policy” [33].

Hyperglycemia in hospital is a common problem and occurs in around 25% of all hospital inpatients. The majority of patients with diabetes are not admitted to hospital to address and treat complications associated with the disease. Control of blood glucose often becomes secondary to the care of the primary diagnosis requiring admission. In patients without diabetes who develop hyperglycemia during an acute illness, high glucose levels are often ignored or treated inappropriately. Poor glycemic control is common among inpatients with diabetes, particularly in those treated with insulin, for many reasons. Poorly defined management plans, poor coordination of care, overly high or absent glycemic targets, lack of therapeutic adjustment, over utilization of “sliding scales” which are often not adjusted to optimize control and under-utilization of insulin infusions represent some of the reasons for poor control of blood glucose. A further important contributing factor has been the fear of provoking hypoglycemia.

Intravenous insulin to treat in-hospital hyperglycemia

Insulin provides the greatest flexibility in the hospital setting to achieve optimal blood glucose control. As protocols for tight glucose control are introduced in a variety of hospital settings it will be essential to implement safeguards to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia and ensure patient safety. The systemic problems that create obstacles to appropriate and safe care of patients receiving insulin in hospital are well recognized [45]. Insulin administration errors could be minimized and clinical outcomes improved by thorough analysis of the setting, additional training for ward staff, setting of goals focused on patient safety, double checking of insulin prescription and administration and regular audit of adverse incidents.

Indications for an intravenous insulin infusion

Whether the patient has previously recognized diabetes or not, insulin provides the greatest flexibility to meet rapidly changing requirements in different hospital settings to achieve optimal blood glucose control. Intravenous infusion of insulin is the only insulin treatment strategy specifically developed for use in the hospital setting. The American College of Endocrinologists advised that intravenous insulin infusion should be used to control glycemia in certain indications (Box 32.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree