Autogenous tissue reconstruction is generally thought to produce the most natural looking and feeling breast(s). Although the permanency of these results and lack of dependancy on a permanent prosthesis is also advantageous, the relative magnitude of these procedures is great. Many women will instead opt for a prosthetic reconstruction, choosing a less invasive operative procedure with a faster recovery and the capability of achieving excellent results. In fact, of the nearly 60,000 women in the United States who had postmastectomy reconstruction in 2007, the majority (approximately 70%) elected to pursue implant-based, postmastectomy reconstruction.1

Current options for implant-based reconstruction include the following: (1) single-stage implant reconstruction with either a standard or an adjustable, permanent prosthesis; (2) 2-stage tissue expander/implant reconstruction; and (3) combined implant/autogenous tissue reconstruction.

Immediate, single-stage breast reconstruction with a standard implant is best suited to the occasional patient who has a small, nonptotic breast and adequate skin at the mastectomy site, which will allow for immediate placement of a permanent implant. Selection criteria for single-stage, adjustable implant reconstruction is similar, yet it is the preferred technique when the ability to adjust the volume of the device postoperatively is desired. In small-breasted women where the skin deficiency is minimal, the implant can be partially filled at the time of reconstruction and gradually inflated to the desired volume postoperatively. In addition, disadvantages of this technique include the placement of a remote port and the need for its subsequent removal. Finally, many suggest that the aesthetic outcomes tend not be as good as 2-stage reconstruction and/or revisional procedures are often necessitated. Consequently, this approach is not used for a majority of implant-based reconstructions.1

Although satisfactory results can be obtained with single-stage reconstruction, in the vast majority of patients, a more reliable approach involves 2-stage expander/implant reconstruction.2 Tissue expansion is used when there is insufficient tissue after mastectomy to create the desired size and shape of a breast in a single stage. A tissue expander is placed in a submuscular pocket at the primary procedure. In the early postoperative period, the tissue expander is serially inflated with saline as a weekly office-based procedure. Once the expansions are completed (6-8 weeks), the tissues are allowed to relax and adjust to the new position for another 1 to 2 months (or until after adjuvant chemotherapy is completed). Exchange of the temporary expander for a permanent implant occurs at a subsequent operation. At the time of the secondary procedure, access to the implant pocket allows for release of capsular contracture, adjustment of the inframammary fold, and selection of the optimum-shaped and optimum-sized implant, which, in turn, maximizes the aesthetic result. Thus the 2-stage technique of tissue expander/implant reconstruction has become the most common approach to implant-based reconstruction.1,3,4

Many patients who undergo postmastectomy reconstruction are candidates for tissue expander/implant reconstruction. However, the absence of an adequate skin envelope is an absolute contraindication to expander/implant reconstruction alone. A large skin resection at the time of mastectomy, due to previous biopsies or locally advanced disease, may preclude the primary coverage of a tissue expander. In patients without the volume of soft tissue required to permit a tension-free closure over an expander, autogenous tissue (most commonly the ipsilateral latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap) can provide additional soft tissue.5 The combination of a latissimus dorsi flap and tissue expansion may also be appropriate in cases in which the remaining mastectomy skin is of insufficient quality to tolerate any tissue expansion. This is typically the case in the insetting of delayed reconstruction after mastectomy and postoperative radiation therapy.6 The addition of autogenous tissue to implant reconstruction increases the length and complexity of the procedure, and addition of a donor site can increase the morbidity. Thus the combined autogenous tissue and tissue/implant reconstruction is generally reserved for a highly select patient population.

Immediate postmastectomy reconstruction is currently considered the standard of care in breast reconstruction. Immediate reconstruction is assumed to be advantageous, as studies have shown that women who undergo immediate reconstruction have less psychological distress about the loss of a breast and have a better overall quality of life when compared with delayed procedures.7 Technically, reconstruction is facilitated in the immediate setting because of the pliability of the native skin envelope and the delineation of the natural inframammary fold. In addition, immediate reconstruction has proven to be cost-effective and is less inconvenient for the patient.

The increasing use of postoperative radiotherapy for earlier-stage breast cancers has, however, challenged this thinking. Adjuvant radiotherapy has been shown to increase the risk of postoperative complications.8-12 Given this data, whether or not to perform immediate reconstruction for patients in whom radiation therapy is planned remains controversial. Similarly, for those who may be unable to decide about reconstruction while adjusting to their cancer diagnosis, delayed expander/implant reconstruction remains an option.

In patients for whom the postoperative administration of adjuvant radiotherapy is likely, a decision to undergo expander/implant reconstruction may be delayed. In the setting of delayed expander/implant reconstruction, placing a prosthesis beneath healed, viable mastectomy flaps eliminates the concern for flap necrosis and expander exposure. However, the amount of skin is often greatly reduced because it comes from non–skin-sparing mastectomies. Therefore, expansion may be more uncomfortable and achieve less volume, making achievement of ptosis difficult.

In the situation where a tissue expander is already in place and the need for radiation therapy becomes evident only after final primary tumor and nodal pathology is available, proceeding with implant reconstruction is still a viable option. In this scenario, patients undergo expansion during chemotherapy, undergo the exchange procedure approximately 4 weeks after chemotherapy, and start radiation therapy as soon as 4 weeks after the exchange procedure. Patients who undergo reconstruction using this approach have been found to clearly have higher rates of capsular contracture; however, a successful reconstruction is still achieved greater than 90% of the time, and patient satisfaction remains high.3,4

The immediate insertion of a tissue expander as a first stage followed by removal and implant placement or removal and autogenous flap reconstruction is an alternative approach offered by some.13 Stage 1 of this 2-stage approach consists of skin-sparing mastectomy with insertion of a tissue expander until the results of the permanent pathology are known. After review of permanent sections, patients who do not require radiation undergo stage 2 of the “delayed-immediate” reconstruction. Those patients who do require radiotherapy undergo deflation of the tissue expander, receipt of radiotherapy, and delayed reconstruction with autogenous tissue alone or combined autogenous tissue–implant reconstruction. Proponents of this approach suggest that patients who require postmastectomy radiation can avoid the aesthetic problems associated with the receipt of radiotherapy after immediate reconstruction. Future larger-scale evaluation of this approach is needed (see Areas of Uncertainty).

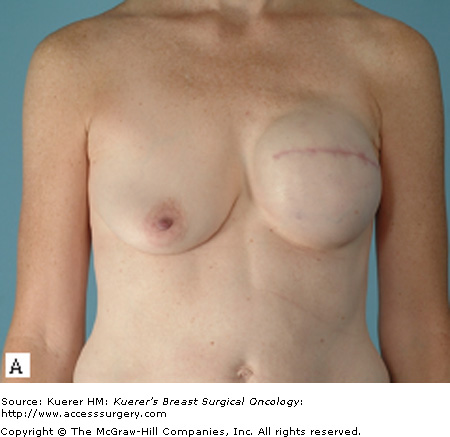

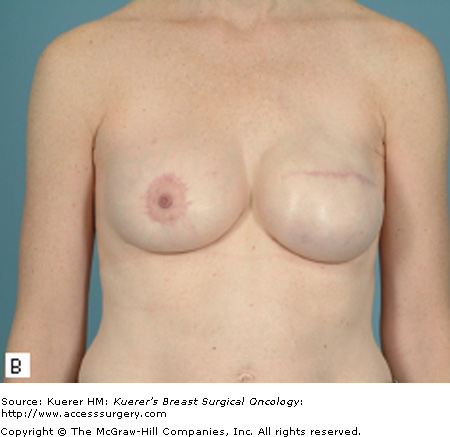

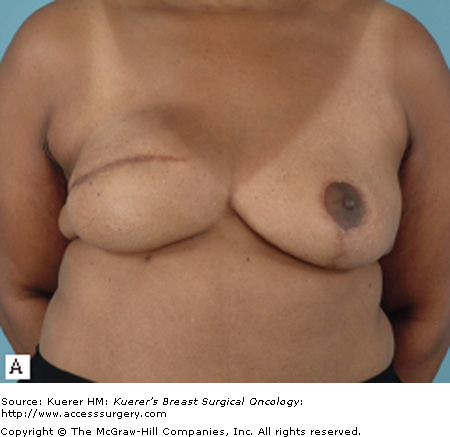

Most patients who undergo a mastectomy will be candidates for tissue expander/implant reconstruction. The most favorable results will be achieved, however, in patients who have a moderate breast volume (500 g or less) and mild to moderate ptosis. Patients with large or markedly ptotic breasts will generally require some type of matching procedure in order to obtain symmetry with a prosthetic reconstruction (Figs. 79-1 and 79-2). Tissue expander/implant reconstruction requires less operative time than does autologous reconstruction; therefore, it may be well suited for patients with comorbidities that preclude long procedures. Patients who undergo bilateral mastectomies may also be well suited to expander/implant reconstruction. Bilateral implant reconstructions can generally produce very favorable results, due to the fact that both breast contour and degree of ptosis are symmetrical.3

Relative contraindications to expander/implant reconstruction include smoking, obesity, and hypertension.14,15 These comorbid conditions have been shown to contribute to increased local wound complications and are associated with an increased risk of reconstructive failure. It is important to note, however, that the overall incidence of complications after tissue expander/implant reconstruction in patients with these identifiable risk factors remains acceptably low. Thus patients who have these factors, such as obesity, should not be discouraged from undergoing expander/implant reconstruction; instead, these patients should be informed about the risks and benefits of the procedure as they pertain to themselves as individuals.

Previous chest wall irradiation and/or postmastectomy radiotherapy are also considered by many to be a relative contraindication for implant-based breast reconstruction. Earlier breast cancers are being increasingly treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in an attempt to increase survival. It has been shown that chemotherapy does not increase the risk of postoperative complications after expander/implant reconstruction.16,17 The possible implications of adjuvant radiotherapy on the outcomes after breast reconstruction are, however, both profound and controversial. Not only is tissue expansion difficult in previously irradiated tissues, but the risks of infection, expander exposure, and subsequent extrusion are increased.18,19 Patients should be offered tissue expander/implant reconstruction only after a preoperative assessment determines the skin quality to be favorable and the presumed ability to perform a skin-sparing mastectomy. In this setting, a relative excess of skin is necessitated in order to permit a tension-free closure over an expander.

Studies have also shown that patients who receive postoperative radiotherapy have a significantly higher incidence of capsular contracture than controls.4,12 Although some view postmastectomy radiation as an absolute contraindication to implant/expander reconstruction because of poor cosmesis and increased complications, others have demonstrated that outcomes may vary with respect to differences in timing and dosing of radiation. Cordeiro et al12 recently published their findings from a large consecutive series of patients who were uniformly treated with radiation 4 weeks after the exchange procedure. Although complication and contracture rates were increased in the tissue/expander group compared with controls, patient ratings of reconstructive success and satisfaction ultimately remained high, confirming similar conclusions made by Krueger et al.11

Postmastectomy implant reconstruction has the distinct advantage of combining a lesser operative procedure with the capability of achieving excellent results in well-selected patients. Donor-site morbidity is eliminated with the use of a prosthetic device, and in general, no new scars are introduced. Where necessary, tissue expansion provides skin with similar qualities of texture and color compared with that of the contralateral breast.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree