Hypopharynx

There is a strong association between tobacco use and the development of hypopharynx cancer.1–3 Due to the rich lymphatic network in this anatomic region, patients commonly present with regional nodal metastases. Many hypopharynx cancer patients also carry significant medical comorbidities and social issues that present additional challenges to the successful delivery of aggressive cancer therapy. As for all complex tumors of the head and neck (H&N) region, multidisciplinary evaluation and management are critical and should involve the H&N surgeon, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, nurse, nutritionist, speech or swallow therapist, and social worker. Although a selected cohort of early-stage tumors may be amenable to organ preservation surgery, more radical surgery such as laryngopharyngectomy is often required for patients who undergo a primary operative approach for hypopharynx cancer. This ablative procedure can induce significant cosmetic and functional changes, and postsurgical rehabilitation efforts guided by knowledgeable professionals are very important to assist in patient adaptation. Increasingly, hypopharynx cancer patients are being considered for nonoperative treatment approaches using definitive radiation or chemoradiation as a means of obtaining tumor control with preservation of organ function. Regardless of the specific treatment approach, all patients require active rehabilitation therapy in an effort to maximize their ultimate speech and swallow function. Despite stepwise advances in the diagnosis and treatment of hypopharynx cancer, the overall outcome for these patients is relatively poor compared with other H&N cancer sites.4 As with most tumors of the H&N region, there is significant interest in combining molecular targeted therapies with traditional cytotoxic therapy in an effort to further improve outcomes.

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

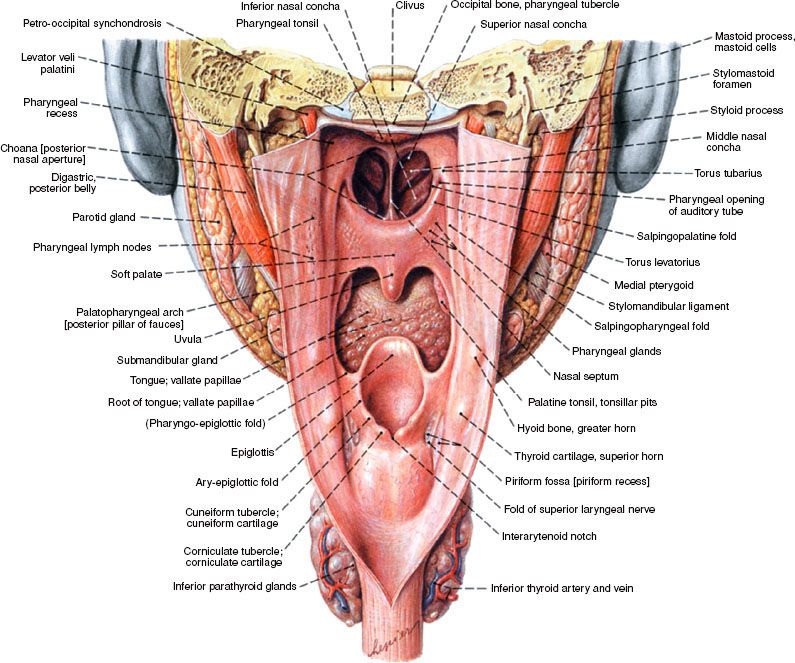

The hypopharynx, sometimes referred to as the laryngopharynx, is contiguous superiorly with the oropharynx and inferiorly with the cervical esophagus (Fig. 46.1). As general landmarks, the superior border of the hypopharynx is demarcated by the hyoid bone and the inferior border by the cricoid cartilage. With regard to cancer diagnosis and staging, there are three primary anatomic subsites within the hypopharynx: the bilateral pyriform sinuses, the postcricoid region, and the posterior pharyngeal wall.

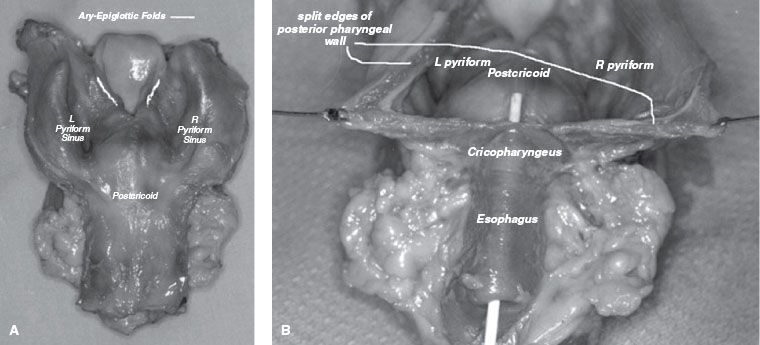

The pyriform sinuses are essentially inverted pyramids with the medial, lateral, and anterior walls narrowing inferiorly to form the apices. Posteriorly, the pyriform sinuses are open and contiguous with the pharyngeal walls. Superiorly, the sinuses are surrounded by the thyrohyoid membrane through which passes the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. Tumor involvement of the sensory branches of this nerve can result in referred otalgia. The postcricoid region is comprised of the mucosa overlying the cricoid cartilage, with the arytenoid and esophageal mucosa forming the superior and inferior borders, respectively. The posterior pharyngeal wall predominantly comprises the squamous mucosa covering the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles and is separated from the prevertebral fascia by the retropharyngeal space. Typically, the mucosa lining the pharyngeal wall is <1 cm in thickness and provides a minimal barrier to direct tumor infiltration. The posterior pharyngeal wall is contiguous with the lateral wall of the pyriform sinus (Fig. 46.2).

Sensory innervation of the hypopharynx is provided by the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve as well as fibers deriving from the glossopharyngeal nerve. The recurrent laryngeal nerve and the pharyngeal plexus provide the primary motor supply. The arterial supply of the hypopharynx is derived primarily from branches of the external carotid artery: superior thyroid arteries, ascending pharyngeal arteries, and lingual arteries.

There is a rich network of lymphatics within the hypopharynx that drain directly through the thyrohyoid membrane and into the jugulodigastric lymph nodes, most commonly involving the subdigastric node. Additionally, there may be direct drainage into the spinal accessory nodes. Tumors involving the posterior pharyngeal wall can also drain to the retropharyngeal nodes, including the most cephalad retropharyngeal nodes of Rouviere.

FIGURE 46.1. Posterior view of the hypopharynx shows the relationship of the pyriform sinus, pharyngeal wall, and postcricoid region within the head and neck. (From Putz R, Pabst R, Sobotta: Atlas der Anatomie des Menschen, 2001. © Elsevier GmbH, Urban & Fischer Verlag München, with permission.)

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

Hypopharynx cancers are relatively uncommon. Approximately 1,800 cases per year were diagnosed annually in the United States from 1990 to 2004,4 and the population-adjusted annual incidence rate in the United States was 0.7 per 100,000 from 2000 to 2008, according to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End-Results (SEER) database.5 Hypopharyngeal cancers accounted for 5.2% of upper aerodigestive tract cancers during that time. Approximately three-fourths of hypopharyngeal cancers occur in men, with a mean age of 65 years. Over 90% of patients with hypopharynx cancer report past cigarette use.6 Alcohol appears to potentiate the carcinogenic effects of tobacco. Additionally, alcohol consumption at medium to high levels for a long period of time can increase the likelihood of hypopharynx cancer in nonsmoking patients.7 The index hypopharynx cancer often occurs within a field of diseased mucosa characterized by high-grade dysplasia. This “field cancerization” reflects widespread mucosal exposure to carcinogens and is responsible for the high rate of synchronous and metachronous primary tumors identified in patients with hypopharynx cancer. Successful counseling with particular emphasis on smoking cessation can enhance treatment tolerance and diminish the risk of developing subsequent cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Patients with occupational exposure to coal dust, steel dust, iron compounds, and fumes have also shown an increased risk for developing hypopharynx cancer.8,9 Overall, the incidence of hypopharynx cancer has shown some gradual decline in the United States. From 1975 to 2001, the incidence decreased by approximately 35%, perhaps as a result of smoking cessation efforts.10

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is well established as a risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the gynecologic tract, particularly uterine cervix. The relation between HPV and H&N cancer is now becoming much better appreciated, particularly for cancers of the oropharynx, where it may approach 60% to 70% in some series. Studies have demonstrated that approximately 20% to 25% of patients with hypopharynx cancer test positive for HPV DNA,11,12 and seropositivity for antibodies against the HPV-16 E6 and E7 antibodies has been associated with a significantly elevated risk of hypopharyngeal cancer.13 The clinical implications of the presence of HPV in hypopharynx cancer are yet to be defined.

There is a recognized increased risk of developing cancers of the postcricoid region for patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome, characterized by iron-deficiency anemia, hypopharyngeal webs, weight loss, and dysphagia.7 Favorable changes in the epidemiology of hypopharynx cancer have resulted from changes in nutrition. The addition of iron to flour has made Plummer-Vinson syndrome quite rare in the upper Midwestern United States and Scandinavian countries where it was formerly more common. An associated decrease in hypopharynx cancer involving the postcricoid region has followed.

FIGURE 46.2. A: Posterior view of resected larynx and hypopharynx specimen afforded by incision through the posterior pharyngeal wall, cricopharyngeus, and cervical esophagus in the posterior midline. The aryepiglottic folds (marked) and arytenoids separate the pyriform sinuses (hypopharynx) from the larynx. B: The three primary anatomic subsites (posterior pharyngeal wall, postcricoid region, and pyriform sinuses) are revealed in this posterior view of the hypopharynx with the posterior pharyngeal wall incised.

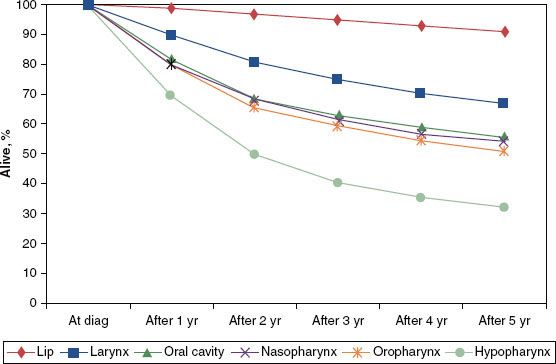

FIGURE 46.3. Five-year survival by mucosal site for head and neck cancers from 1990 to 1999 cases. (From Cooper JS, Porter K, Mallin K, et al. National Cancer Database report on cancer of the head and neck: 10-year update. Head Neck 2009;1:748–758, with permission.)

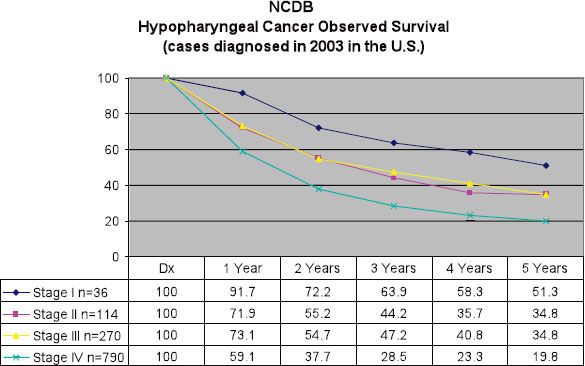

FIGURE 46.4. Observed survival for hypopharyngeal cancer in the United States is calculated for new cases identified in the NCDB in 2003 and includes all pathologic types and the selected anatomic sites: C129, C130, C131, C132, C138, C139. Staging according to sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. (From National Cancer Data Base. Commission on Cancer. American College of Surgeons. Benchmark Reports. Available at: http://cromwell.facs.org/BMarks/BMPub/Ver10/bm_reports.cfm, with permission.)

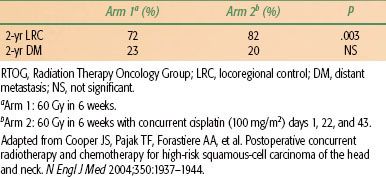

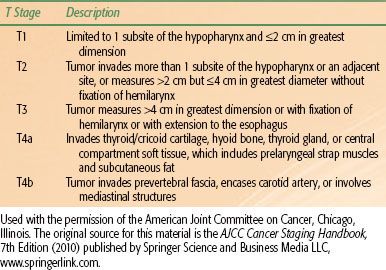

TABLE 46.1 AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE ON CANCER 2010 T STAGING FOR HYPOPHARYNX CANCER

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Several prognostic factors have been identified for patients with hypopharynx cancer. Age, particularly older than 70 years, has been identified as an unfavorable predictor of outcome.7 This may simply reflect the diminished likelihood of elderly patients to successfully tolerate the aggressive therapy approaches required for locoregionally advanced cancers of the H&N. Women have been found to achieve somewhat improved outcomes compared to men, although this may in part be a manifestation of earlier-stage disease at diagnosis.14,15 In addition, tumor location has an impact on outcome, with cancers of the pyriform sinus generally faring better than those arising in the postcricoid or posterior pharyngeal wall regions.14,15 As a whole, hypopharynx cancer patients fare poorly in comparison with patients harboring tumors from other H&N sites (Figs. 46.3 and 46.4).4,16 To a lesser extent, tobacco, alcohol, and dietary factors (carotenoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, and flavonoids) may also have an impact on outcome.17

Biologic factors have been investigated for their potential role in hypopharyngeal cancer. The presence of p53 gene mutations has been associated with bulkier tumors and younger patients along with higher expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). However, p53 has not shown correlation with multiple primary tumors, tumor grade, or DNA ploidy.18,19 Further, there are conflicting data regarding the prognostic significance of EGFR expression for patients with hypopharyngeal cancer.20 Some studies suggest EGFR overexpression portends a worse prognosis for patients undergoing (chemo)radiotherapy but not for patients treated with primary surgical resection.21,22

STAGING

STAGING

The most commonly used staging system for hypopharynx cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) 2009 seventh edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook and is based on a combination of clinical and radiographic data (Table 46.1).23 No significant changes were made between the sixth and seventh editions other than to alter the classification of extension to the esophagus (previously T4a, from the tumor-node-metastasis [TNM] classification) toT3. The nodal and group staging is similar to other sites within the pharynx with the exception of nasopharynx. Although AJCC staging is a useful tool to broadly group similar cancer types, it should not be used as a blueprint for management. Patient factors, including age, comorbid medical conditions, and motivation for organ preservation, are beyond the scope of the staging system but nevertheless represent important factors for consideration with each individual patient.

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

Local Extension

It is sometimes difficult to definitively assign tumor origin to a specific subsite in the hypopharynx when the tumor overlaps more than one subsite. Of the hypopharynx cancer cases recorded in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER database between 2000 and 2008, 83% of tumors with a known subsite arose in the pyriform sinus. An additional 9% arose from the posterior pharyngeal wall, and 4% originated in the postcricoid region.5

Due to the high propensity for advanced primary disease as well as regional nodal involvement, the majority of hypopharynx cancer patients present with stages III and IV disease. In a retrospective study from Washington University, 87% of patients with cancers of the pyriform sinus and 82% of patients with posterior pharyngeal wall tumors presented with stage III or IV disease.24

Cancers arising from the pyriform sinus may spread superiorly to involve the aryepiglottic folds and arytenoids and invade the paraglottic and pre-epiglottic space. Lateral tumor extension can involve portions of the thyroid cartilage, allowing entry into the lateral compartment of the neck. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often useful for optimal assessment regarding the extent of tumor invasion. For tumors arising from the medial wall, the most common site of involvement for pyriform sinus tumors, there is a likelihood of tumor involvement of intrinsic muscles of the larynx resulting in vocal cord fixation. Inferior tumor extension beyond the apex can involve the thyroid gland.

Cancers arising within the postcricoid region can extend circumferentially to involve the cricoid cartilage or anteriorly to involve the larynx with resultant vocal cord fixation. Tumor involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve can also precipitate vocal cord fixation. Primary postcricoid tumors are often quite extensive and can involve the pyriform sinus, trachea, or esophagus. As a result, these tumors generally carry a worse prognosis in comparison to tumors from other subsites of the hypopharynx.14 Nodal spread to the paratracheal nodes and inferior deep cervical nodes is not uncommon. Tumors arising from the posterior pharyngeal wall can extend to involve the oropharynx superiorly, the cervical esophagus inferiorly, and the prevertebral fascia and retropharyngeal space posteriorly.

Many cancers of the hypopharynx have a propensity for submucosal spread. It can therefore be difficult to accurately quantify the full microscopic extent of disease. This is particularly true for cancers of the posterior pharyngeal wall and postcricoid regions. Careful study through serial sectioning of surgical specimens has identified that 60% of hypopharynx cancers demonstrate subclinical spread with a range of 10 mm superiorly, 25 mm medially, 20 mm laterally, and 20 mm inferiorly.25 This extensive pattern of tumor infiltration can present considerable challenge in the effort to achieve clear surgical margins or full dosimetric coverage with radiotherapy.

Regional Disease

Due to the rich lymphatic drainage of the hypopharynx, more than 50% of patients will manifest clinically positive cervical lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis, and ultimately 65% to 80% of patients will have nodal involvement, as 30% to 40% of N0 necks harbor micrometastatic disease when electively dissected.26 Jugular chain nodes, levels II to IV, as well as retropharyngeal nodes are all at high risk of harboring regional metastases in patients with hypopharynx cancer. Postcricoid tumors may also spread directly to pre- and paratracheal nodal basins. In light of cross-draining lymphatics, there is a significant risk of bilateral cervical node metastasis (Fig. 46.5).27,28

Distant Metastases

The most common site for distant metastasis to develop in patients with cancer of the hypopharynx is the lung. Previously, approximately one-quarter of patients diagnosed with hypopharynx cancer presented with distant metastases, although this incidence in more recent reports is estimated at approximately 16%.29 For those patients not rendered free of locoregional disease following initial therapy, the incidence of distant metastases increases notably with the length of time following initial treatment.30

Field Cancerization

Carcinogens can induce dysplastic changes throughout the mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract, leading to an increased risk for field cancerization that enhances the likelihood of synchronous or metachronous secondary primary tumors. Approximately 7% of patients with hypopharynx cancer will manifest a second primary tumor at initial diagnosis and between 10% to 20% will develop a secondary primary tumor over time. In fact, this second tumor risk is a significant cause of mortality in patients who survive more than 2 years following initial treatment.6

FIGURE 46.5. Nodal distribution patterns for a series of 267 patients with hypopharynx cancer as summarized by admission records at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. (From Lindberg R. Distribution of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. Cancer 1972;29:1446–1449, with permission.)

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

In light of the nonspecific nature of early symptoms, the majority of patients with cancers of the hypopharynx present with advanced local or regional disease. Frequently, there is a delay between presentation and diagnosis as patients are often managed for presumed infectious or gastrointestinal etiology. The majority of symptoms are related to local tumor spread, including dysphagia and odynophagia. There may be frank pharyngeal obstruction, invasion of constrictor muscles, prevertebral space invasion, or strap muscle invasion. Common presenting signs and symptoms include dysphagia, sore throat, hoarseness, weight loss >10 pounds, and neck mass. The majority of patients present with more than one of these signs and symptoms.31 Roughly 25% of patients will present with clinical stage III disease and 50% with clinical stage IV disease; however, reflux symptoms can be a common presentation leading to diagnosis of stage I or II hypopharyngeal tumors.6 Selected patients may first come to medical attention with complaints of unilateral ear pain (referred otalgia) due to tumor involvement of the visceral sensory nerves of the pharynx.

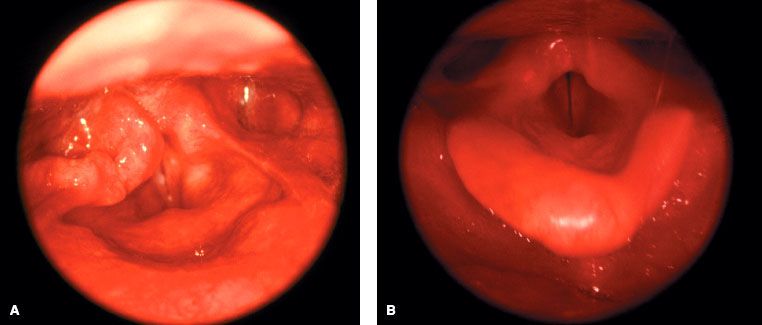

FIGURE 46.6. A: Outpatient clinic photograph taken through a rigid endoscope mounted with a 35-mm camera of a newly diagnosed exophytic T2 tumor arising from the right pyriform sinus with involvement of the adjacent aryepiglottic fold. There was no compromise of vocal cord mobility, and clinical staging of the primary lesion was T2. B: Photographic examination 1 year following 70-Gy radiation and concurrent cisplatin chemotherapy with complete tumor regression and excellent functional status of the laryngopharynx. Note mild to moderate mucosal edema of supraglottic structures following high-dose radiation.

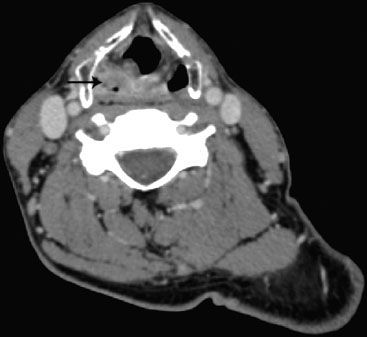

FIGURE 46.7. Axial computed tomography image from the same case as in Figure 46.6, depicting the T2 hypopharynx tumor involving the right pyriform sinus.

PRETREATMENT EVALUATION AND STAGING WORKUP

PRETREATMENT EVALUATION AND STAGING WORKUP

A comprehensive workup for patients with cancers of the hypopharynx should include a detailed history focusing on the duration of symptoms, amount of weight loss, the presence of otalgia, changes in voice quality, and degree of dysphagia. A previous history of another upper aerodigestive tract malignancy and a history of tobacco smoking are commonly associated. The physical examination should include direct and indirect visualization of the full laryngopharyngeal axis with particular attention to the size, location, and anatomic positioning of the primary tumor as well as the mobility status of the true vocal cords. Dentition and oral health should be assessed. If the patient presents with cervical adenopathy, the size, number, location, texture, and mobility of these nodes should be documented.

Although cervical adenopathy associated with hypopharynx cancer may be analyzed with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, there is little value in this approach, because most patients will receive advanced radiographic imaging to further define the nodal involvement. On rare occasions FNA may be useful to help distinguish other coexisting causes of lymphadenopathy such as lymphoma. Most patients will undergo a direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia in conjunction with esophagoscopy. This panendoscopy allows not only biopsy confirmation of the primary tumor site, but also mapping of the extent of the tumor as well as the ability to survey for synchronous primary tumors (Fig. 46.6A). Use of transnasal fiberoptic techniques makes it possible for a panendoscopy to be done for selected patients without anesthesia in the clinic setting.

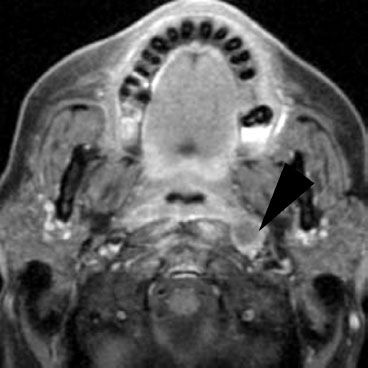

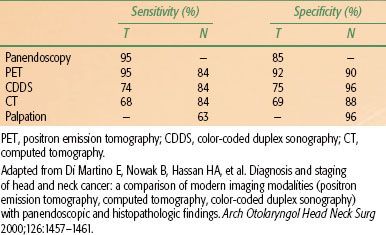

In addition to panendoscopy, patients should undergo either high-resolution CT with contrast (or MRI) extending from the skull base to below the clavicle to help assess the extent of the primary tumor and to quantitatively and qualitatively assess cervical adenopathy (Figs. 46.7 and 46.8).27 Although a chest x-ray has traditionally been used to assess for the presence of pulmonary metastasis, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) imaging (with accompanying CT for coregistration) is increasingly used to assess the extent of regional adenopathy and to survey for the presence of distant metastasis. FDG-PET is becoming an increasingly valuable adjunct to CT or MRI in the radiation treatment planning process, particularly for patients treated with conformal intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) or tomotherapy techniques. Di Martino et al.32 compared CT, PET, color-coded duplex sonography, palpation, and panendoscopy in assessment of tumor and nodal status. The results of this study are summarized in Table 46.2 and support the promising sensitivity and specificity of PET scanning in H&N cancers. Schwartz et al.33 examined standardized uptake value (SUV) of primary and nodal metastasis in H&N cancer patients and their relationship to clinical outcome. A primary tumor SUV >9.0 was associated with a significantly lower local recurrence-free survival and disease-free survival. However, there was no correlation between nodal SUV and clinical outcome.

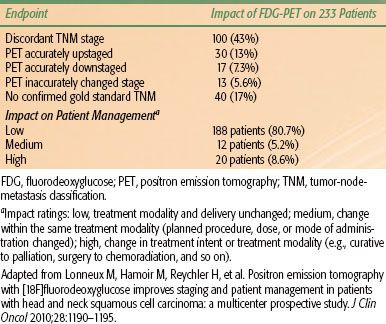

A recent prospective multicenter study of 233 H&N squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) patients (including 46 hypopharyngeal cancer) highlighted the potential impact of PET imaging on H&N SCC management.34 TNM staging and therapeutic decisions were first determined based on conventional workup, and then physicians were unblinded to FDG-PET data and asked to restage the patients and reanalyze their therapeutic decisions. PET and conventional workup revealed discordant TNM staging in 100 patients (43%). PET was deemed significantly more accurate than conventional staging and improved the staging in 20% of patients. Incorporation of PET data ultimately impacted management in 32 patients (13.7%) (Table 46.3), supporting the use of FDG-PET in H&N SCC staging.

Many patients with hypopharynx cancer present with concurrent medical and social comorbidities that require consideration before initiating cancer-directed therapy. Commonly, there is a progressive history of dysphagia and odynophagia with associated weight loss. Whether these patients are treated with surgical or nonsurgical approaches, a gastrostomy tube may need to be considered as a temporary measure. It is important to optimize or at least stabilize the patient’s nutritional status prior to initiating definitive therapy.

It is valuable for hypopharynx cancer patients to undergo evaluation by a speech and swallow therapist to determine the degree of dysfunction prior to therapy. This may be done as a bedside study of swallowing capacity, a fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing, or (usually preferably) through the more definitive fluoroscopic barium swallow study. This modified barium swallow study is called a cookie swallow, video pharyngogram, or oropharyngeal motility study and is most commonly done with a speech pathologist in attendance. If objective swallowing dysfunction is present, patients may be taught adaptive techniques to improve the effectiveness and safety of their oral intake. Additionally, close follow-up with the same speech and swallow therapist is highly desirable during and after therapy to maximize the patient’s long-term functional capabilities.

Because many hypopharynx patients have an active history of alcohol and tobacco use, it is important to counsel accordingly and encourage all patients to take advantage of methods and programs to facilitate smoking and alcohol cessation. All patients should undergo comprehensive dental evaluation and cleaning as well as basic education regarding oral hygiene. For patients treated with conventional radiation therapy techniques, there is a significant likelihood of long-term xerostomia that can promote dental decay. If existing dentition is in poor condition, dental extractions should be considered prior to therapy, particularly for teeth that will reside within the high-dose radiation region. Typically 10 to 14 days are required following dental extractions to allow for healing prior to the initiation of radiation therapy. Custom fluoride carrier trays should be fabricated and discussed for long-term use in an effort to diminish the rate of dental decay for patients with chronic xerostomia.

Finally, many patients with hypopharynx cancer will have social issues, including lack of family support, financial limitations, transportation issues, poor nutrition, and hygiene habits that may hamper their ability to successfully receive adequate care. Often, the involvement of a case manager or social worker is of central importance to assist patients who require support both during as well as following cancer therapy.

FIGURE 46.8. Axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image scan with fat-saturation depicting metastatic lateral retropharyngeal node with evidence of central necrosis and peripheral enhancement.

TABLE 46.2 COMPARISON OF VARIOUS MODALITIES FOR STAGING

TABLE 46.3 IMPACT OF FDG-PET ON STAGING, MANAGEMENT FOLLOWING CONVENTIONAL WORKUP

PATHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION

PATHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION

In SEER data from 2000 to 2008, 93.9% of hypopharynx cancers were squamous cell carcinoma, with lymphoma, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma each accounting for approximately 0.5% of cases.5 Similarly, the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) Benchmark Reports evaluated 17,654 cases of hypopharyngeal cancer in the United States between the years of 2000 and 2008. Over 90% of cases were SCC.16

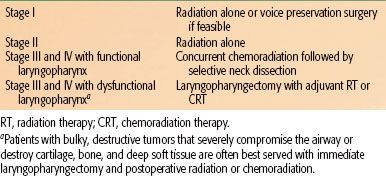

TABLE 46.4 GENERAL TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS BASED ON HYPOPHARYNX TUMOR STAGE

TABLE 46.5 FIVE-YEAR ONCOLOGIC OUTCOMES FOR TRANSORAL MICROLASER SURGERY FOR T1 OR T2 HYPOPHARYNGEAL TUMORS

MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT

For patients presenting with early-stage, resectable disease, voice-preserving surgery and definitive radiotherapy alone are viable and acceptable treatment options. The vast majority of patients, however, present with stage III or IV disease and warrant multimodality treatment. A key consideration in determining the favored approach for these patients is the likelihood and motivation to preserve laryngopharyngeal function (Table 46.4).

Primary Surgery

T1 and T2 Tumors

Contemporary indications for primary surgical management of patients with early cancers of the hypopharynx include those with a history of previous H&N radiation, those in whom organ conservation approaches are deemed possible, and those who refuse radiation. Even for hypopharynx cancer patients who will receive nonoperative treatment approaches, it remains critical for the H&N surgeon to remain actively involved. The role of the surgeon in these cases may include endoscopic biopsy with detailed assessment of tumor extent, methods to secure the airway (tracheotomy or laser debulking), and methods to ensure adequate nutrition (gastrostomy). The surgeon will also play a vital role in multidisciplinary oncologic follow-up after nonoperative treatment.

Selected T1 and T2 hypopharynx cancers may lend themselves to surgical excision. These favorable subsites include the upper pyriform sinus and the posterior pharyngeal wall. The standard supraglottic laryngectomy encompasses the aryepiglottic fold and may be extended to include part of the arytenoids, the base of the tongue, and the upper pyriform sinus. Small cancers isolated to the posterior pharyngeal wall may be removed by endoscopic laser resection or removal using an open approach. Dysphagia requiring nothing by mouth status is common from an open approach, especially if reconstruction of the posterior wall is effected with an adynamic and insensate free flap. Relative contraindications to organ conservation surgery for hypopharynx cancers include cartilage invasion, vocal fold fixation, postcricoid invasion, deep pyriform sinus invasion, and extension beyond the larynx.

Innovations with free-flap reconstruction have allowed retention of speech, swallowing, and breathing functions of the larynx despite extensive resection by way of a hemilaryngopharyngectomy. The temporoparietal flap and radial forearm free flap coupled with rigid cartilaginous support have been employed to retain function in patients with hypopharynx cancers without extension to the postcricoid region or apex of the pyriform sinus.35

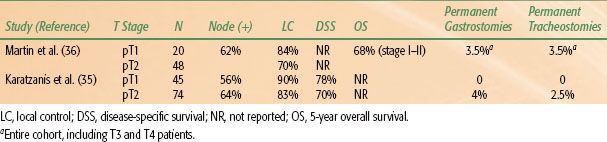

In recent years, advancements in organ preservation surgery have included the use of transoral laser microsurgery and transoral robotic surgery. For selected cases, these approaches can achieve oncologic tumor removal, while limiting normal tissue disruption, thereby potentially avoiding tracheostomy and the use of feeding tubes.36–39 This approach may involve concurrent or delayed neck dissection following transoral resection of the primary lesion (to allow for final margin assessment). The necks in some T1N0 patients may be observed with close interval follow-up CT scans. Adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy is utilized in the majority of patients using this approach (see “Postoperative Radiotherapy” below for indications) and should generally encompass the primary tumor site as well as bilateral necks and supraclavicular fossae. Recent results have demonstrated that appropriately selected T1 or T2 lesions can achieve negative margins by transoral laser microsurgery or transoral robotic surgery.36 Oncologic outcomes appear similar to open surgical approaches using this technique and are likely accompanied by lower rates of permanent gastrostomy tube or tracheostomy placement (Table 46.5).

T3 or T4 Resectable Tumors

Favorable T3 hypopharynx cancers that present in the upper aspect of the pyriform sinus and allow full extirpation by either an extended supraglottic laryngectomy or extended vertical partial laryngopharyngectomy with free flap reconstruction are infrequent. Most T3 and T4 hypopharynx cancers that are treated surgically will require total laryngectomy with efforts to preserve a posterior strip of the hypopharynx spanning the oropharynx to the esophagus. This preserved posterior wall of the hypopharynx may be tubed and closed on itself in selected cases. In the past it was common practice to accept primary reconstruction of this segment as adequate for swallowing if closure over a nasogastric tube was possible. More recently primary closure has been discouraged for cases with less than a 3- to 3.5-cm width of posterior pharyngeal wall mucosa to tube on itself. Most commonly superior swallowing results when the anterior and lateral walls of the remaining hypopharynx are reconstructed with a pedicled or free flap.

For more bulky tumors of the hypopharynx, total laryngopharyngectomy, removal of the larynx and the entire hypopharynx, is required. This procedure creates a gap between the oropharynx and esophagus that must be reconstructed with a tubed fasciocutaneous flap such as the radial forearm free flap or anterolateral thigh flap, a free jejunum, or a tubed pedicled myocutaneous flap. The myocutaneous flaps are technically difficult to tube due to the bulk of the fat and muscle underlying the skin paddle.

Laryngopharyngectomy with esophagectomy may be performed if the hypopharynx cancer extends inferior to the cricopharyngeus to ensure the inferior margin. In this case, gastric pull-up or colon interposition are reconstructive options used to restore the conduit for food and saliva extending from the oropharynx to the stomach.

TABLE 46.6 RESULTS OF RTOG POSTOP CHEMORADIATION TRIAL