Major Concepts

Diseases

Bacteria of the Ehrlichieae group cause several tickborne infections of humans and animals which include human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME; caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis), human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA; caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum), human disease due to Ehrlichia ewingii, and sennetsu fever (caused by Neorickettsia sennetsu). Tickborne fever of sheep, cattle, and goats and pasture fever of sheep, cattle, bison, deer, and rodents, as well as serious disease in horses, dogs, and cats, may resulting from infection with A. phagocytophilum as well.

Symptoms

Although many ehrlichial infections remain asymptomatic, severe illness may occur, with up to half of infected individuals hospitalized. Early symptoms include fever, malaise, muscle and bone aches, headache, and gastrointestinal abnormalities with or without rash. Blood cell numbers are decreased. Serious disease manifestations include prolonged fever, kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, meningoencephalitis, seizures, coma, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Death occurs in 2% to 5% of the cases for HME and 7% to 10% of cases of HGA. The latter is associated with fungal or viral infection, possibly indicating an immunosuppressive effect of the bacteria. Immunosuppressed persons, especially those who are HIV-positive, are more likely to develop severe disease: the fatality rate in this group is 25%. Alveolar damage and interstitial pneumonia; lymphohistiocytic infiltrates; focal necrosis of the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes; and diffuse hemorrhaging may occur during cases of lethal infection. E. ewingii also causes serious disease in immunosuppressed persons. Sennetsu fever is a rare and mild disease.

Infection

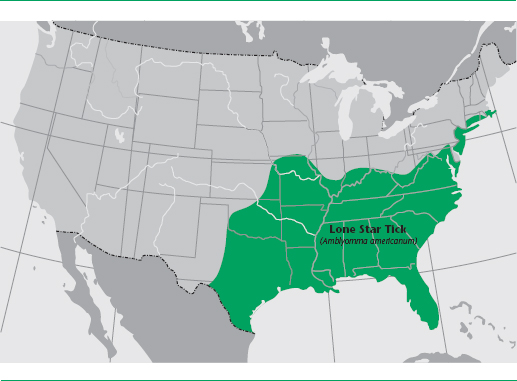

The ehrlichial bacteria are small, obligate, intracellular, gram-negative cocci residing within phagocytic white blood cells, such as monocytes and macrophages or neutrophils, in which they may form microcolonies called morulae. E. chaffeensis is transmitted primarily by adult lone star ticks. High rates of infection occur in Arkansas, North Carolina, Missouri, Oklahoma, New Jersey, and Tennessee. Because these diseases are tickborne, the majority of cases occur in rural settings or, less commonly, in suburban locations. The median age of infected individuals is 44 years, and males are more commonly infected than females. Persons spending large amounts of time in wooded areas (foresters, rangers) have an increased risk of infection. A. phagocytophilum is spread by nymphal and larval stages of the blacklegged and western blacklegged ticks in the United States and is found in Connecticut, Minnesota, Rhode Island, New York, Wisconsin, and California. HGA is also found in a number of European countries, including Slovenia, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Croatia, Poland, Italy, Austria, and France. A number of animal species serve as reservoir hosts for these bacteria, including white-tailed deer, dogs, wolves, coyotes, sheep, cattle, goats, horses, and some rodents.

Immune Response

Protective immunity against ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis is provided by CD4+ T helper cells and CD8+ T killer cells, the cytokines interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, and antibodies produced by B lymphocytes. Ehrlichia bacteria evade the immune response by (1) not expressing lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan typically used by immune cells to recognize bacteria, (2) preventing lysosomes from fusing with endosomes containing bacteria, (3) failing to activate enzymes within the host cells that generate bacteriotoxic reactive oxygen species, and (4) blocking apoptotic self-destruction by infected cells.

Treatment and Prevention

HME and HGA may be successfully treated by antibiotics such as doxycycline, another tetracycline, or rifampin. Preventive measures include avoiding exposure to or attachment of ticks, their prompt removal, and elimination of tick habitat.

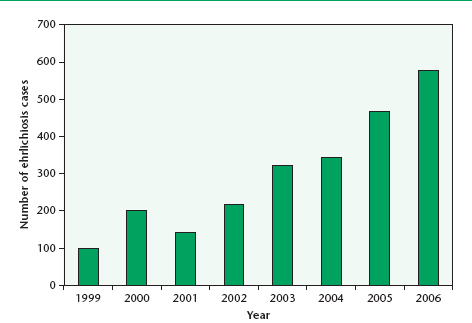

Some 1,200 cases of human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis were reported to the CDC between 1986 and 1997. Ehrlichia species are found globally, mainly in temperate regions of the world. Individuals with antibody reactivity to Ehrlichia chaffeensis have been seen in countries as diverse as Argentina, Belgium, Israel, Italy, Mali, Mexico, Portugal, Thailand, and the United States. Human infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum has been reported in Belgium, Denmark, Hungary, Slovenia, and Sweden, and antibody reactivity to the granulocytic form has been found in Germany, Israel, Italy, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States.

Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tickborne zoonoses and are transmitted by some of the same vector species as Borrelia burgdorferi, resulting in the possibility of coinfection. Most infections occur during the spring and summer (55% to 70% between May and July), reflecting times of greatest exposure to the appropriate life stage of the tick vectors. Infection rates are higher among older adults (usually over the age of 40), with the highest rates found in adults aged 70 to 79. The resulting diseases, when present, range in severity from mild to very severe, especially in immunosuppressed persons. In addition to humans, infection is found in many common domestic and wild animal populations.

The first human disease found to result from infection with an Ehrlichia-like species was sennetsu fever, caused by Neorickettsia (formerly Ehrlichia) sennetsu, in Japan in 1953. This is a mononucleosis-like illness with fever and swollen lymph nodes. It is very rare, with most of the cases occurring in western Japan and Malaysia. There have been no reported deaths.

Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME) was described in 1986 in Arkansas and is found mainly in the southern and southeastern parts of the United States. The causative bacterium was isolated in 1990 from Fort Chaffee, Arkansas. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA; formerly human granulocytic ehrlichiosis) was first recognized by Johan Bakken in 1994 after the discovery of microcolonies of an Ehrlichia-like species in a patient’s neutrophils.

One of the important factors in the recent increase of HGA is the explosive rise in the population of white-tailed deer, which increased an estimated 50-fold during the twentieth century. The deer is the primary host for all stages of the tick vector. Populations of other hosts for this tick, including the wild turkey and the coyote, have grown as well. There has also been an increase in the number of humans particularly vulnerable to severe disease manifestations, including individuals who are older, have cancer, or are immunosuppressed.

Infected individuals may remain asymptomatic. In those in whom disease does develop, symptomatic illness follows an incubation period of five to ten days. Initial signs include fever, malaise, muscle and bone aches, headache, and gastrointestinal abnormalities. Rash may or may not be present, in contrast to Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a similar condition in which rash is typically found. Individuals may become severely ill, and up to half of them require hospitalization. Severe reactions occurring in these illnesses include prolonged fever, kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, meningoencephalitis, seizures, coma, or adult respiratory distress syndrome. Death occurs in 2% to 3% of the cases, with HME being more pathogenic, while HGA infection may lead to serious secondary infections due to A. phagocytophilum–induced loss of neutrophil competence. Individuals with prior immunosuppression are at the highest risk for severe disease manifestations.

Human Monocytotropic Ehrlichiosis (HME)

HME is a moderate to severe disease whose symptoms include fever (occurring in more than 95% of cases), headache (60% to 75%), myalgia (40% to 60%), nausea (40% to 50%) and vomiting (36%), joint pain (30% to 35%), rash (35%, mostly pediatric cases or HIV-positive adults), cough (25%), sore throat, diarrhea, swollen lymph nodes, abdominal pain, and neurological symptoms (meningitis- or encephalitis-like illness, cognitive impairment) (10% to 40%). Adult respiratory distress syndrome may also occur. Laboratory reports often indicate a decrease in the numbers of red blood cells (50% of cases), white blood cells (60% to 70%), and platelets (70% to 90%), accompanied by increased lymphocyte counts (45% to 85% of the white blood cells). Elevated levels of liver enzymes (transaminase—80% to 90%; alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin—25% to 60%) occur. Hyponatremia (decreased urination) is seen in up to 50% of infected adults and 70% of infected children. Serum sodium levels may be under 130 milliequivalents per liter. Some 41% to 63% of patients are hospitalized (median duration of seven days). HME closely resembles the granulocytic forms of the disease, but rash, central nervous system involvement, and gastrointestinal disturbances are more common.

Asymptomatic cases have also been reported but not conclusively documented. Disease is particularly severe in the immunosuppressed and may involve acute kidney or respiratory failure, metabolic acidosis, a profound decrease in blood pressure, widespread blood clotting within vessels (disseminated intravascular coagulopathy), liver failure, adrenal insufficiency, and myocardial dysfunction. One study indicated a 25% mortality rate in immunosuppressed patients; 67% of the fatalities were HIV-positive. Respiratory symptoms in patients with severe disease may include interstitial pneumonitis, pulmonary edema, pleural effusions, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Other hematological manifestations include pulmonary or conjunctival hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, subdural hematoma, and bloody urine (hematuria). Secondary infections with cytomegalovirus, Candida, and Aspergillus suggest that immunosuppression may be occurring. The overall mortality rate is 2% to 5%. In immunosuppressed patients with fatal outcome, alveolar damage and interstitial pneumonia; lymphohistiocytic infiltrates; focal necrosis of the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes; and diffuse hemorrhaging have been seen. In a retrospective study of 133 HIV-positive individuals in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1999, two cases of HME were detected by indirect immunofluorescence, for a seroincidence rate (percentage of persons with antibodies to the microbe) of 6.7% among symptomatic individuals and an overall rate of 1.6%. One of the two patients required hospitalization. False negative readings by serology are possible due to the suppressed immunity found in this population.

Both cell-mediated and humoral immunity appear to play important roles in defense against attack by E. chaffeensis. Major histocompatibility complex class II antigens, TLR4, and production of IL-6 by macrophages have been implicated in efficient clearance of bacteria. SCID mice, which lack mature T and B lymphocytes, do not survive infection. In the absence of anti-ehrlichial antibodies, infected monocytes produce the cytokines IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10, while in the presence of hyperimmune serum, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α are also made. Several of these cytokines are proinflammatory or induce fever. Lymphocytosis (elevated lymphocyte count) is a common finding, with unusually high numbers of rare CD3+CD4−CD8− γ∼GD T cells. This T cell subset is also elevated during infection with other intracellular pathogens, such as Listeria, Mycobacterium, and Leishmania species.

HME is spread primarily by nymphal or adult lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum, but bacteria have been found by PCR in the dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) and the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) as well. Both male and female ticks feed on humans, but the females are believed to be primarily involved in disease transmission. All stages of the tick life cycle bite humans, and prevalence ranges from 5% to 15%. Adult ticks may acquire their infections by transstadial transmission from the nymphal stage or directly by feeding on an infected vertebrate host. Transovarial infection of eggs or unfed larvae has not been documented. White-tailed deer (definitive host), dogs, wolves, goats, coyotes, and red foxes are naturally infected with E. chaffeensis and may serve as disease reservoirs. This tick may be found in meadows, woodlands, and hardwood forests. No incidence has been reported in rodents. From 1997 to 2001, there were 503 cases reported in the United States; 338 of these were confirmed, occurring in 23 states, particularly in Arkansas, North Carolina, Missouri, Oklahoma, New Jersey, and Tennessee. The incidence rate is 7 to 57 per 1,000,000 population. Severe HME has been found to be more common in Georgia and North Carolina than Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a tickborne disease that it resembles.

FIGURE 4.2 Lone star tick

Source: CDC/Amanda Loftis, William Nicholson, Will Reeves, and Chris Paddock.

Most of the cases occur in rural locations and the remainder primarily in suburban locales. The majority of cases are found in males (more than twice as often as in females), and the median age of patients is 44 years.

Human Granulocytotropic Anaplamosis (HGA)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree