!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC “-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.1//EN” “http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml11/DTD/xhtml11.dtd”>

33HPB Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Injuries to the liver, extrahepatic biliary tree, and pancreas are often deadly and always challenging. This area is also commonly referred to as the “surgical soul.” They will engage all of your senses, test your skills, and demand great teamwork from you and your colleagues.

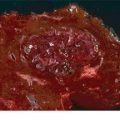

HEPATIC INJURIES

Although textbooks are often filled with a complex hierarchy of operative interventions and maneuvers for treating hepatic trauma, the vast majority of liver injuries are treated nonoperatively. This process involves diagnosis with cross-sectional imaging (CT), serial clinical observation, and laboratory (hemoglobin, white blood cell count [WBC], and liver function tests/enzymes) monitoring. This algorithm allows the clinician to successfully treat and predict both the initial injury and potential complications such as delayed/ongoing hemorrhage and interval formation of a biloma. Clearly, any patient who presents with hypotension and/or peritonitis (i.e., concurrent injuries) requires emergent operative therapy.

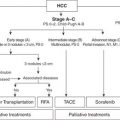

Management

Preoperative Considerations

The dominant challenge with hepatic trauma is management of the hemodynamically unstable patient with ongoing hemorrhage from a high-grade liver injury. These patients often present in physiologic extremis and therefore require damage control resuscitation techniques. Early recognition of their critical condition, as well as immediate hemorrhage control, is essential to survival.

Patients with major injury caused by blunt trauma or right upper quadrant penetrating mechanisms must undergo an immediate F.A.S.T. (i.e., Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) examination in the trauma bay to confirm the presence of large-volume intraperitoneal fluid. This exam is repeatable and can be used to reevaluate patients in urban centers who present immediately following their injuries. Massive transfusion protocols as part of a damage control resuscitation must be initiated early during the patient assessment process. If the patients rapidly stabilize their hemodynamics, they should undergo an emergency CT scan of the torso (blunt and gunshot). If they remain clinically unstable, however, patients must be transferred to the operating theater without delay. Hemorrhage control is the dominant driver in these patients. Collateral issues such as optimal intravenous access, imaging of other areas (brain, spine, bones), and fracture fixation are important but, nevertheless, secondary priorities. In summary:

1.In hemodynamically stable patients without CT evidence of a hepatic arterial blush or other reasons to proceed to the operating theater, admission and close observation are warranted.

2.In hemodynamically stable patients with a hepatic arterial extravasation/blush, immediate transfer to the interventional angiography suite (or hybrid O.R.) is mandated for hepatic angiography and/or portography with selective embolization. Autologous clot or absorbable embolization medium is optimal.

3.In patients with persistent hemodynamic instability, immediate transfer to the operating theater for laparotomy is essential. Delays will lead to loss of life.

Operative Care and Technical Tips

The patient should be rapidly prepared and draped with available access from the neck to the knees. Vascular instruments and balloons must be open and ready within the theater. A midline laparotomy from xiphoid process to pubic bone should be performed with three passes of a sharp scalpel. The peritoneal cavity should be packed in its entirety with laparotomy sponges for patients with blunt liver injuries. The falciform ligament should be left intact to provide a medial wall against which to improve medial packing pressure. The right upper quadrant (and midline vascular structures) should be evaluated prior to any intraperitoneal packing for penetrating injuries. If hemorrhage continues, an early Pringle maneuver (clamping of the porta hepatis with a vascular clamp) is mandated. This is both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. If bleeding continues despite application of a Pringle clamp, a retrohepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) or hepatic venous injury is likely. Critically injured patients in physiologic extremis do not tolerate extended Pringle maneuvers to the same extent as patients with hepatic tumors undergoing elective hepatic resection. Forty minutes represents the upper limit of viability. If the liver hemorrhage responds to packing (which describes the vast majority of cases 85% to 99% depending on the series) but continues to hemorrhage when unpacking is completed, the patient should be repacked and transferred to the ICU with an open abdomen once damage control of concurrent injuries is complete. Cover the liver with a plastic layer of sterile x-ray cassette material to avoid capsular trauma upon eventual unpacking. Topical hemostatic agents are also helpful. If control of the liver hemorrhage is dependent on maintenance of a Pringle maneuver despite packing (i.e., the retrohepatic IVC hematoma has ruptured), call for senior assistance, mobilize the right lobe, and suture the IVC or hepatic veins with 4-0 Prolene on SH needles or 5-0 Prolene on RB1 needles (assuming that a replaced left hepatic artery is not the source of inflow occlusion failure). These patients may also require total vascular exclusion (TVE) of the liver (complete occlusion of the infrahepatic IVC, suprahepatic IVC, porta hepatis (Pringle maneuver), as well as an aortic cross-clamp within the abdomen). If TVE is pursued without concurrent clamping of the aorta, the patient will arrest due to a lack of coronary perfusion. I prefer to obtain suprahepatic IVC control within the abdomen in patients with a normal length of IVC inferior to the diaphragm. An alternate option includes access of the IVC within the pericardium itself (i.e., as it enters the heart). This 2-cm length of IVC is easily accessible by opening the pericardial sac after dividing the diaphragm. Alternatively, the suprahepatic IVC can also be accessed from the thorax if a thoracotomy has already been performed. Veno–veno bypass is also a theoretical option but rarely used due to a lack of transplant training for most trauma/general surgeons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree