Breast cancer is being detected at earlier stages due to improvements in imaging and increased public awareness of the breast health guidelines. The American Cancer Society recommends monthly self-breast exams, an annual clinical breast exam (CBE), and annual screening mammography for women over 40.1 With increased compliance, primary care physicians are being overwhelmed with self-reported breast lumps or changes in the CBE or mammogram. Prompted in part by fear of litigation of missed breast cancer coupled with patient demand for expertise in breast diseases, referrals to breast specialists or diagnostic breast clinics (DBCs) are increasing. In fact, a whole new generation of breast surgeons is cropping up to meet this demand.

Despite specialization, the foundation of any new patient evaluation begins with a comprehensive history and physical examination. The information gained will then guide the ordering of appropriate imaging studies. This chapter’s goal is to outline the necessary information for an appropriate evaluation of common breast problems.

Evaluation of common breast problems at our institution occurs in diagnostic breast clinic that has on-site imaging including a dedicated breast MRI. Our 3 advanced registered nurse practitioners (ARNPs) see over 1500 patients per year under the supervision of 4 breast surgeons. The ARNP performs a complete history and physical examination, has any outside films reviewed by our on-site breast radiologist, obtains any additional imaging needed, and designs a plan with the breast surgeon. Image-guided core biopsies are performed a few days later to allow for insurance approval, cessation of blood-thinning agents, and to accommodate the patient’s schedule. Rarely excisional biopsies are used as the primary diagnostic procedure. Biopsy results are given by the ARNP and patients with benign results are followed for 2 years with CBE and diagnostic imaging. Excisional biopsies are performed if the core biopsy revealed atypia.

The first step in the evaluation of a new patient involves obtaining a thorough history and physical examination in a patient and supportive manner, as many women will present with significant anxiety. The patient must be considered the expert on her own body, and her concerns must be given every consideration. She must feel empowered to perform breast self-exams and feel comfortable seeking evaluation for changes. Fortunately for most, the outcome will be benign, but the initial approach is similar for all patients.

The essential elements of the history should include the chief complaint (symptoms) such as skin changes, nipple inversion/retraction, nipple discharge, redness, breast pain, and palpable changes. Detailed analysis of symptoms should include onset, duration, precipitating/alleviating factors, recent trauma or infection, changes in medications, changes in weight, changes in medical conditions. Additionally, previous breast history should be recorded including details of prior breast biopsies, breast augmentation/reduction, breast problems, compliance with screening guidelines, and imaging history. Exploring the past medical history can elicit relevant risk factors or comorbidities. In addition, certain conditions such as diabetes mellitus or congestive heart failure can affect the breast. Allergies are important to note. Medications can affect the breast as well, most commonly by causing nipple discharge. Coumadin and aspirin can contribute to a bloody discharge. Reproductive history includes age at menarche, menstrual and pregnancy history, breastfeeding, and use of hormones (contraception, infertility treatment, and hormone replacement). This information is important in evaluating the breast on clinical exam or imaging and assessing risk of breast cancer. The date of the last menstrual period must be taken into consideration on CBE and any diagnostic breast imaging obtained, especially breast MRI. Family history of cancer is important for individual risk assessment and potential need for genetic counseling. Social history is not unique to evaluation of breast patients, but is helpful in determining patient support and resources. Additionally, smoking is associated with poor wound healing and increases risks of infection such as a recurrent retroareolar abscess. The history of alcohol intake is important, especially when assessing males for gynecomastia. Prior breast imaging with reports should be reviewed in conjunction with current imaging. Outside films should be reviewed at the facility for concordance. Similarly, any outside pathology slides should be reviewed at the institution’s pathology department to confirm diagnosis, especially when atypia are found on a core needle biopsy.

History-taking should be conducted with the woman fully clothed and preferably not on the examination table, making her more comfortable and less vulnerable. Then when it is time for the physical examination, have the gown (cape) open to the front. Consider having a chaperone for this part even if you are the same sex as the patient.

Assessment begins from the first moment, whether it’s observing the patient walking to the exam room or an interaction while taking vital signs. Is she cradling one of her breasts? Observe the overall demeanor of the patient, and eye contact. Is there anyone accompanying the patient for the consultation?

Although the most important part of the examination is the CBE, a thorough, relevant physical exam is ideal. Start with the patient in the sitting position and palpate the cervical region for lymphadenopathy and thyromegaly (thyroid conditions are common with breast diseases). Also include an assessment of any supraclavicular or infraclavicular lymphadenopathy. Examine the heart and lungs, and assess for peripheral edema, pulses, spinal tenderness, and costovertebral angle tenderness. While the patient is still sitting, the CBE includes elements of inspection and palpation of the breast and axillae. Stand in front of the patient, open her gown without removing it, and have her press her hands into her hips. Then have her move her arms slowly out to her side and continue moving her arms until they are above her head. Look for size, shape, symmetry (most women have slight differences), and changes in the contour of the breast (retraction, puckering, dimpling, bulging, and changes in the nipple). Inspection includes the entire breast and nipple looking for edema, erythema, rashes, and ulceration.

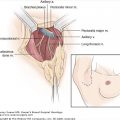

For palpation, begin with a superficial exam, allowing the woman to trust your touch. Watch her facial response as you do the examination. This is also an ideal opportunity to assess the comfort level of self-exams and to provide teaching in the technique. Palpation is performed by placing one hand underneath her breast for support. With your other hand palpate the entire breast mound. Relax the breast and then exam in the axilla by cradling her arm in yours and supporting the elbow. Palpate the axillary contents from the latissimus muscle, behind the pectoralis muscle, to the ribcage. Moving her arm will allow entry to the apex of the axilla. Palpation begins with the pulp of the fingers and insinuation inside the axilla with the arm initially raised, and then lower, allowing for better appreciation of the subclavicular and central group of nodes on deep palpation. Palpation along the chest wall and the subscapularis should also be routinely performed. Any palpable lymph node is evaluated for size, mobility, consistency, and for evidence of matted lymph nodes. The skin overlying the axilla and the ipsilateral arm should also be examined for presence of any sinus tracts, previous surgeries, or signs of infection. Lymph nodes may be palpably enlarged from folliculitis, an arm infection, or even acrylic nails, but they should be soft and mobile. Document any palpable nodes for future reference. Suspicious lymph nodes need further assessment with imaging. Repeat your exam on the other side.

Have the patient recline for the abdominal exam and a repeat of the CBE. A variety of techniques for CBE exist, such as the radial search pattern, the concentric circular pattern, and the MammaCare method.2-4 This latter method utilizes the vertical strip pattern and adaptations continue to be recommended today.5 In this pattern, the pads of the 3 middle fingers are used with light, medium, and deeper levels of pressure applied at each area of tissue palpated. The key is consistency in the individual technique and that the entire breast is reliably and reproducibly examined. The area to be examined includes the tissue from the clavicle to the inframammary ridge and from mid-sternum to mid-axillary line. The superficial tissue as well as the deeper layers of breast tissue should be examined in a thorough pattern. Subtle changes may be noted, including areas of thickening, in addition to palpable masses. Nodularity of the breast tissue is usually more prominent in the upper outer quadrants and shortly before the menstrual flow. Avoid squeezing the nipple unless there is a history of spontaneous nipple discharge.

CBE is a skill that improves with experience. Standardized training with simulated breast models has been evaluated, and increased comfort levels in medical students were seen with training.6-8 Residents’ ability to detect breast masses improved utilizing a standardized vertical strip, 3-pressure method. This effort incorporated a self-study program and a trained patient surrogate in addition to the use of a silicone model.7 The use of deep pressure and the time spent performing the exam both correlated significantly with finding a breast mass. Core components of this technique included “consistent search pattern, deep palpation, circling downward, and adequate overlap of coverage.” Documentation also improved with the training initiative. In a randomized controlled trial of CBE training, Campbell and associates found duration of the exam to be an independent predictor of sensitivity.8 The bottom line is that a thorough CBE takes time.

Documentation of the CBE should include any pertinent positive and negative findings. Any palpable areas of concern noted on CBE or by the patient should be indicated by position (clock face and centimeters from the nipple), size, shape, depth, attachment to overlying skin or chest wall, associated skin changes, and mobility. This provides pertinent information for further evaluation by diagnostic imaging, possible biopsy, and appropriate follow-up.

Pain is typically considered a “warning sign.” This can vary in different cultural contexts, but most individuals in the United States consider pain to equate with a physical problem. In fact, it is the most common breast-related complaint seen in primary care clinics and affects some 70% of women.9 An underlying fear of breast cancer is what prompts these patients to seek health care. Although the vast majority of breast cancers do not hurt, the woman may relate an anecdotal story of a friend who had breast pain for years before her cancer was detected. Thus, a significant amount of time will be spent listening, reassuring, and seeking to prove that it is not breast cancer. About 85% of women with mild to moderate mastalgia are successfully managed with just reassurance.10

Breast pain without imaging abnormality is the hardest subset of breast pain to treat, as the causative agent usually cannot be identified. In a minority of women, the pain is a result of a change in hormonal status, as with perimenopause, stopping or starting birth control pills, or hormone replacement therapy. Treatment is supportive. If the pain arises from initiating birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy and does not abate in a few months, consider switching the brand.

Next, deduce whether the pain is cyclical or noncyclical. Cyclical breast pain peaks just before the menstrual flow begins and mostly involves the upper outer quadrants of the breasts. First and foremost, treatment is reassurance and then supportive—sleep with a sports bra, intermittent anti-inflammatory medicine, and a trial of limiting caffeine intake. If persistent and significantly impacting her quality of life, one can consider medical therapy. Fortunately cyclical breast pain is more responsive to medical intervention than noncyclical mastalgia.11

Supplement a general history and physical examination with an assessment of when it began, duration, aggravating and alleviating factors, whether it is unilateral or bilateral, point location or generalized through the breast, description of the character of the pain (sharp, burning, throbbing, itching, dull ache), and any new medications or health problems. This type of mastalgia is not associated with the menstrual cycle, can involve any part of the breast especially the inner breasts, and can be unilateral or bilateral. A CBE should identify areas of abnormality in terms of point tenderness, mass, or skin/nipple retraction; then a mammogram and a focused ultrasound should be performed. Treatment should be directed at any underlying factor if one is identified.

If no culprit is found, assess the impact of caffeine withdrawal and wear a sports bra while sleeping for 1 month. The belief is that the sports bra stabilizes the breast, minimizing inflammation.12 She can repeat the cycle of wearing the sports bra as needed.

One can also offer a trial of vitamin E 400 U/day for 1 month (Fig. 12-1). Vitamin E, a lipid-soluble antioxidant, acts as a defense against oxidative stress and has been used to treat breast pain for over 40 years. Despite this fact, only limited clinical trials using vitamin E are available, showing little or no benefit over placebo or other agents such as danazol.12,13 In our experience, it either works or it does not. If the vitamin E does not work, try evening of primrose oil (EPO) 3 g daily for 4 months. EPO is a rich source of essential fatty acids that lessens inflammation via the prostaglandin pathway. Both vitamin E and EPO take weeks before showing any effect. Studies using EPO have shown a benefit in breast pain reduction upwards of 58% in cyclical breast pain, 38% in noncyclical mastalgia.11 Yet a recent meta-analysis failed to show any benefit from EPO.14 Despite conflicting results, EPO has the most tolerable side-effect profile and should be tried before prescription medications are attempted.

EPO failures commit to a daily diary recording each and every episode of pain with descriptors. She is to return for a CBE, review of the log, and repeat imaging in 2 months (6 months from presentation). Most women do not return for several reasons: (1) the pain is better; (2) realization that the pain is not as “constant” as they thought; (3) they were not compliant with keeping the log. If, however, she returns, take the time to review the log looking for a pattern or causative events that may be treatable. If no cause can be elicited and repeat CBE with imaging remains negative, embark on a trial of medical management aimed at quieting the breast via hormonal manipulation. Tamoxifen 10 mg daily, danazole 200 mg a day, or bromocriptine 1.25 mg at night can be offered. A common breast cancer treatment, tamoxifen blocks estrogen receptors and has the fewest side effects compared to danazole or bromocriptine. The success rate is upward of 80% to 90% by 6 months with a 30% relapse rate.15 Due to a risk of endometrial cancer with use over 6 months’ duration, the recommendation is to stop therapy at 6 months. Danazole, an anti-gonadotropin, acts on the pituitary–ovarian axis, and bromocriptine is an inhibitor of prolactin secretion. Both danazole (used for endometriosis) and bromocriptine (used for amenorrhea and nipple discharge) are more effective than tamoxifen but at the cost of being much less tolerable. Many women thus opt out of trialing these medications, but those that do often find that side effects are worse than the breast pain itself and self-discontinue. If they stay on the medication, 77% with cyclical breast pain will have significant benefit versus 19% in the placebo control arms.10 The noncyclical mastalgias do not fare quite as well, with a 44% response to drug therapy versus 9% in the placebo group.10 If the woman fails therapy with one agent, try another drug, as about one-third of women will respond to second-line therapy. At the Cardiff Mastalgia clinic, the women with cyclical breast pain who had an excellent or substantial response to medical management had an 80% chance of long-term reduction of significant breast pain 6 months after stopping the medication, but the women with noncyclical mastalgia had only a 40% chance of long-term benefit.10

Focal pain without imaging abnormality should be followed for a minimum of 1 year with CBE and imaging to confirm the localized pain was not from a very early breast cancer. Other agents such as neurontin have been used with limited success for the treatment of pain caused by herpes zoster and postmastectomy pain syndromes, but there are no controlled trials in the literature using neurontin for benign breast pain.

Costochondritis (Tietze syndrome) is inflammation of the costochondral joint spaces and is common in all ages of women, especially middle-aged women. Inflammation can be trauma or sports-related and leads to irritation of the intercostal nerves. The medial intercostal nerves that traverse these joint spaces supply sensation to the medial and central portion of the breast. Gently pushing on the joint spaces will elicit the breast pain; no abnormalities will be identified within the breast. Confirmation is obtained by lifting the breast off the chest wall while the woman is supine and palpating the breast sideways to avoid applying pressure on the joint spaces. No pain within the breast will be invoked by this maneuver. A similar phenomenon can occur laterally where the ribs curve anterior and the lateral intercostal nerves travel to get to the lateral breast. Trauma to the ribs in this area, spasm or irritation of the latissimus muscle, and herpes zoster all can lead to aggravation of these nerves and thus pain on the lateral to central aspects of the breast. On physical examination, pain can be elicited by pressing on the ribs in the anterior axillary line or latissimus muscle.

Costochondritis is predominantly a unilateral process (92% of the time) and involves either medial or lateral nerves but not both.16 Treatment is supportive. Steroids with local injection of anesthetics are also effective therapies.16 Duration is weeks to months long (mean time = 17 months) before symptoms resolve.

The most common cause of point tenderness with a corresponding imaging abnormality is a simple cyst. Other causes of focal mastalgia with imaging abnormalities but without skin changes include gynecomastia, fibroadenoma, diabetic mastopathy, lactating adenomas, galactoceles, and certain cancers (phyllodes tumor, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and lymphoma).

Mastalgia with skin changes, for the most part, will have an underlying etiology. Skin changes can be a color change, skin edema or thickening, exaggeration of hair follicles, rash, or dimpling/retraction of the skin. The skin of the breast is similar to skin elsewhere and the disease process may be of skin origin, such as intradermal inclusion/sebaceous cysts, hydradenitis (usually affecting the skin on the lower half of large pendulous breast), eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and yeast infections of the inframammary fold (usually affects larger-breasted women). Chronic yeast infections result in a hyperpigmented outline of the pendulous breast on the abdominal skin.

A simple cyst can become inflamed or infected causing pain. If that cyst is pushing on the overlying breast skin, the skin can appear red/pink. If the area is confirmed to be a cyst on ultrasound, aspiration should be performed.

Mondor disease or superficial thrombophlebitis of the breast is an uncommon entity with an incidence less than 1%.17 Common causes include trauma, tight clothing, infections, and surgical procedures of the breast, and rarely include cancer. One-third of the time no inciting event or cause can be found. The history is one of a sudden development of localized pain in the breast followed by a visible and palpable tender cordlike groove under the native breast skin. The overlying skin may be red from inflammation. These veins are usually branches of the lateral thoracic vein or thoracoepigatric vessels.18 Interestingly, the presentation is more common in middle-aged women. On physical examination the “cord” is easily palpable as a long tubular structure. Mammogram will be normal or show a tubular density. Ultrasound will show a hyperechoic cordlike lesion with possibly an intraluminal thrombus. Fortunately, the process is self-limiting and resolves in 2 to 8 weeks. Warm compresses, anti-inflammatory medications, and loose-fitting clothes are usually all that is necessary. Rarely surgical intervention is warranted to remove the affected area or rule out cancer.

A woman presents with a pink or red heavy breast. Important to elicit in the history is duration of symptoms, insidious or abrupt onset, change or growth of the area of color over time, trauma, bug bites, nipple discharge, pain, systemic symptoms, and history of breast, axillary, or shoulder surgery. Physical exam should try to differentiate erythema (inflammation/infection) from hyperemia. With the woman supine, lift her breast off the chest wall and hold for several minutes. Observe if the pink hue fades as the breast drains (hyperemia). In inflammation (cellulitis), the redness persists and the breast is usually painful whereas hyperemia is not sensitive to touch. Anytime a woman presents with redness or a pink hue to the breast, the surgeon must eliminate inflammatory breast cancer from the differential. Most times it can be made by clinical presentation and appearance of the breast, but sometimes imaging and a punch biopsy of the affected skin are necessary.

Hyperemia can be accompanied by varying degrees of skin edema (exaggeration of the hair follicles, pitting, and thickness of the skin). The hyperemia and edema are caused by blockage of drainage (venous or lymphatic) from the breast and are usually found centrally and in the lower breast skin in pendulous breasts. Causes are seromas from breast biopsies or lumpectomies, curvilinear incisions in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, axillary surgery (sentinel lymph node biopsy, axillary node dissection), breast radiation, trauma, resolving infection, superficial vasculitis, and sometimes in young women hormonal variation. The history and physical findings will guide what diagnostic imaging to order. The mammogram is useful for identifying masses within the breast, demonstrating skin thickening and edema within the breast parenchyma, or no abnormality. The ultrasound can demonstrate a seroma/hematoma, an abscess, cancer recurrence, axillary adenopathy, or recurrence. If venous congestion is suspected (history of central venous access devices, congestive heart failure, or trauma to the shoulder/clavicular area), then ultrasound, venography, or echocardiogram may be warranted.19 Treatment of the underlying diagnosis will alleviate the hyperemia in most cases. For women without a treatable cause, the process is usually self-limited, but breast massage by a lymphedema specialist may be beneficial. Breast compression garments are helpful but are not well tolerated by the woman.

Erythema is not dependent on the position of the breast for drainage. It can be focal from an underlying abscess or diffuse from cellulitis or mastitis. The history should attempt to decipher if the origin was within the breast spreading to the skin or vice versa. Bug bites, spider bites, cat scratches, poison ivy, and so forth should be treated as appropriate for the specific type of skin infection. Mastitis, on the other hand, originates in the breast, is most commonly pregnancy/lactationally related, and treated by the patient’s obstetrician. The woman is referred if she fails to improve, if an abscess develops, or to rule out cancer as the underlying cause. An abscess less than 3 cm in greatest diameter is treated with ultrasound-guided aspiration with irrigation of the cavity.20-21 Oral antibiotics are also given and the success rate is ~90% with a single aspiration. For those failing this treatment or having a larger abscess, the surgical treatment is incision and drainage. Mastitis in a nonlactating woman is less common and is called periductal mastitis.22 Periductal mastitis is more common in younger women and in smokers (more than 10 cigarettes/day). Smoking increases risk of abscess and fistula formation (78% in smokers).23,24 These women present with a red, hot, uncomfortable breast and may have systemic complaints such as fever. The cause of the infection is usually unknown but can be related to oral or hand contact to the nipple–areolar complex. Many organisms have been identified including Staphylococcus and rare organisms such as Mycobacterium species. Imaging should be aimed at identifying an abscess and allaying fears of an underlying cancer. If there is an abscess, treatment consists of ultrasound-guided aspiration. The fluid is sent for culture and sensitivity to allow for antibiotic selection. Operative management is warranted for fistulas and if conservative measures fail.

Recurrent retroareolar abcesses are associated with squamous metaplasia of the lactiferous ducts (SMOLD). SMOLD is commonly identified in smokers and leads to peri-areolar fistulous tracts despite antibiotics, incision, and drainage. The treatment includes treating the active infection and smoking cessation. The fistulous tract, the abscess, and the affected nipple duct need to be removed.25

Patients may also present with a chief complaint of a palpable area (lump) noted on self-exam, CBE, or by a partner/significant other. This palpable area may not be a new finding. A variety of reasons may postpone evaluation: financial hardship or access to health care, denial of breast changes, fear, anxiety, or blaming it on a past traumatic injury. Some women wait until a menstrual cycle prior to making an appointment. An abnormal mammogram or breast sonogram will prompt self-examination or recollection of previous palpable concerns. Males of all ages tend to delay seeking evaluation. Regardless, all palpable concerns merit a thorough evaluation. The majority of changes evaluated will ultimately reveal benign disease, but the patient’s perception of the experience lays the groundwork for the future. A woman’s breast cancer risk increases with age and she must feel comfortable seeking evaluation should another problem arise in the future.

In conjunction with the history and physical exam, ascertain characteristics and duration of the lump. If premenopausal, ask about changes in reference to her menstrual cycle. Palpable changes can present as subtle thickening, focused nodularity, discrete mass, or as multiple palpable changes. Women of all ages may present with diffuse fibronodular changes, making the assessment challenging. Normal glandular tissue can be mistaken for a mass, but skilled CBE can help differentiate this. A common finding on ultrasound of palpable abnormalities is a prominent fat lobule.

Triple assessment refers to the combination of CBE, breast imaging, and biopsy. In women younger than 30 years of age, a focused breast ultrasound should be the initial diagnostic imaging study. In women aged 30 and older, both a diagnostic mammogram and focused ultrasound are recommended. The requisition for diagnostic imaging should specify the exact location of any palpable masses. Ultrasound can determine a cystic versus solid mass and may identify abnormalities not evident on mammogram. Diagnostic mammography in symptomatic women has a higher sensitivity and lower specificity than screening mammography.26 Negative imaging prompts a short-term follow-up with CBE and imaging in 3 to 4 months. If clinically suspicious, biopsy should not be delayed if the imaging was negative.

Solid breast masses require histocytologic diagnosis. Percutaneous core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) offer less invasive alternatives to surgery and can further help distinguish solid from cystic lesions. Ariga and associates evaluated FNA in women with palpable breast masses in a study of 1158 FNA procedures subsequently confirmed on histopathology.27 Sensitivity and specificity were 98%, positive predictive value 99%, and the false-negative rate 9%. In women upto 40 years, a malignancy was diagnosed in 51%, and 74% in those older than 40. Correlation of lesions seen on both mammogram and sonogram is important to avoid missing a lesion. Concordance between imaging and pathology is another critical component of the assessment. Prompt communication of the results to the patient will allay anxiety.

Breast cysts are often seen in pre- and perimenopausal women (aged 35-50), but can be seen in women of all ages. Women often find cysts on self-exam and relate a history of a rapidly enlarging palpable change. Cysts can be single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, tender, firm, mobile, and can vary in size from a few mm to very large. They are well circumscribed and anechoic on ultrasound. Oil cysts can be idiopathic or result from trauma or previous surgery and are confirmed on mammogram.28 Complex cysts have both anechoic and echogenic (solid) findings on ultrasound and can be due to fibrocystic change and resolving cysts. Ultrasound-guided aspiration and/or core biopsy is recommended if a solid component or intracystic mass is seen on imaging. Hematomas and seromas are tender, palpable fluid collections seen after surgery or trauma. Fat necrosis, a very firm mass, can appear as a complex cyst on ultrasound and is common after surgical procedures here there is local destruction of fat cells. On mammogram the indeterminate calcifications, spiculated areas of increased opacity, and focal masses mimic a malignancy. A tissue diagnosis will confirm the diagnosis.29

Fibroadenomas are benign tumors of the breast that are composed of stromal and epithelial (glandular) cells and are most commonly seen in younger women, typically during their 20s and 30s, but can occur in older women. It is the most common breast lesion in adolescence and typically is a firm, rubbery, mobile mass that is well circumscribed, but can be lobulated and irregular. Multiple fibroadenomas (defined as 3 to 5 lesions in one breast) occur in 10% to 15% of patients with the diagnosis. Giant fibroadenomas by definition are greater than 5 cm or 500 g.30

A retrospective study of 605 women under the age of 40 with palpable breast masses detected on self-exam (n = 484) and on CBE (n = 121) found a dominant mass detected on CBE by a surgeon in 36% and 29% of the women, respectively.31 Fibroadenoma proved to be the most common diagnosis in this group at 57%; cysts accounted for 10%. In addition, carcinoma was diagnosed in 18% of the young women in this study, including biopsies indicated for abnormal mammographic findings unrelated to any palpable mass. Vargas found fibroadenoma to be the most common diagnosis (72%) in over 500 young women and cysts accounted for 4%, fibrocystic changes 3%, and malignancy 1%.32 Interestingly, 53% of abnormalities detected on self-exam were true masses compared to 18% detected by primary care providers.

Phyllodes tumors (formerly termed cystosarcoma phyllodes) are similar to fibroadenomas but much less common. They occur later in life, typically after the fourth decade, but can be seen in adolescence. In addition to a palpable, rubbery, mobile mass, these patients may present with benign lymphadenopathy. A classic presentation is a lump that suddenly popped up after a trauma. On CBE and imaging they may be impossible to differentiate from a fibroadenoma and therefore require diagnostic biopsy. A review of 443 phyllodes cases (median age of 40 years) found 64% were benign, 18% borderline, and 18% malignant.33

Papillomas, friable tumors with a central fibrovascular core, can be associated with palpable masses and are sometimes intracystic lesions. Solitary papillomas are often associated with nipple discharge. Multiple peripheral papillomas may appear as lobulated masses or clusters of punctuate calcifications on mammogram. Intracystic, intraductal, and solid masses can be seen on ultrasound.28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree