After completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Distinguish among the causes of localized versus generalized, soft tissue versus mucocutaneous, and acquired versus congenital bleeding. 2. List laboratory tests to differentiate among acquired hemorrhagic disorders of trauma, liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, and kidney failure, and interpret results when given. 3. Interpret laboratory assay results to diagnose and subtype von Willebrand disease. 4. Use the results of laboratory tests to identify and monitor the treatment of congenital single coagulation factor deficiencies such as deficiencies of factors VIII, IX, and XI. 5. Explain the principle and rationale for the use of each laboratory test for the detection and monitoring of hemorrhagic disorders. 6. Discuss the laboratory monitoring of therapy for hemorrhagic disorders. Hemorrhage is a severe form of bleeding that requires intervention. Hemorrhage may be localized or generalized, acquired or congenital. To establish the cause of either a bleeding event or a patient’s tendency to bleed, the physician must obtain a complete patient and family history and do a thorough physical examination before ordering diagnostic laboratory tests.1 Generalized bleeding may exhibit a mucocutaneous or a soft tissue (anatomic) pattern. Mucocutaneous hemorrhage may be manifested as bruises or purpura, purple lesions of the skin caused by extravasated (seeping) red blood cells (RBCs).2 Petechiae and ecchymoses are purpura of less than or greater than 3 mm, respectively, and the presence of more than one such lesion may indicate a disorder of primary hemostasis. Other symptoms of defects of primary hemostasis are menorrhagia (profuse menstrual flow), bleeding from the gums, hematemesis (vomiting of blood), and epistaxis (uncontrolled nosebleed). Although nosebleeds are common and mostly innocent, especially in children, they suggest a primary hemostatic defect when they occur repeatedly, last longer than 10 minutes, involve both nostrils, or require physical intervention or transfusions. Mucocutaneous hemorrhage tends to be associated with thrombocytopenia (platelet count lower than 150,000/mcL), qualitative platelet disorders, von Willebrand disease (VWD), or vascular disorders such as scurvy or telangiectasia (see Chapters 43 and 44). A careful history and physical examination distinguishes between mucocutaneous and anatomic bleeding, and the distinction helps direct investigative laboratory testing and treatment. Anatomic (soft tissue) hemorrhage is seen in acquired or congenital defects in secondary hemostasis, or plasma coagulation factor deficiencies. Examples of anatomic bleeding include recurrent or excessive bleeding after minor trauma, dental extraction, or a surgical procedure. In such cases, hemorrhage may immediately follow a traumatic event, but is often delayed or recurs minutes or hours after the initial blood flow is stopped. In other patients, anatomic bleeding episodes are spontaneous. Most anatomic bleeds are internal, such as bleeds into joints, body cavities, muscles, or the central nervous system, and may initially have few visible signs. Because joint bleeds cause swelling and acute pain, they may not be immediately recognized as hemorrhages, although hemophilia patients usually know what is happening from experience. Repeated joint bleeds (hemarthroses) cause painful inflammation, with swelling and permanent cartilage damage that immobilize the joint. Repeated joint bleeds cause painful inflammation and permanent cartilage damage that swells and immobilizes the joint. Bleeds into soft tissues such as muscle or fat may cause nerve compression and subsequent temporary or permanent loss of function.3 When the bleeding involves body cavities, it causes symptoms related to the organ that is affected. Bleeding into the central nervous system, for instance, may cause headaches, confusion, seizures, and coma and must be managed as a medical emergency. Bleeds into the kidney may present as hematuria and may potentially be associated with acute kidney failure. Whenever a soft tissue or mucocutaneous generalized hemostatic disorder is suspected, hemostasis laboratory testing is essential. Emergency department physicians often must begin to intervene in cases of acute hemorrhage, even before taking a history or waiting for the results of laboratory assays. In these instances, group-matched or O-negative RBCs, frozen plasma (FP), platelet concentrate, cryoprecipitate, recombinant activated coagulation factor VII (rFVIIa; NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk, Inc., Princeton, N.J.) or the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron, Pfizer, New York, N.Y.) may be used to correct coagulation factor and platelet deficiencies to stop hemorrhage.4–6 Box 41-1 lists symptoms that suggest generalized hemorrhagic disorders. Liver disease, kidney failure, chronic infections, autoimmune disorders, obstetric complications, dietary deficiencies such as vitamin C or vitamin K deficiency, blunt or penetrating trauma, and inflammatory disorders may all be associated with coagulopathy. If a patient’s bleeding episodes began after infancy, are associated with some disease or physical trauma, and are not duplicated in relatives, they probably are caused by an acquired, not a congenital, condition. When an adult patient comes for treatment of generalized hemorrhage, the physician first looks for an underlying disease or event and takes a personal and family history. The important elements of patient history are age, sex, current or past pregnancy, any systemic disorders such as diabetes or cancer, trauma, and exposure to drugs, including over the counter drugs or drugs of abuse. The physician determines the trigger, location, and volume of bleeding, then orders laboratory assays (Table 41-1). The initial coagulopathy test profile should consist of a complete blood count (CBC) that includes a platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and fibrinogen assay.7 These tests take on clinical significance when the history and physical examination already have established the existence of abnormal bleeding. They are not effective as screens for healthy individuals. TABLE 41-1 Screening Tests for a Generalized Hemostatic Disorder Congenital hemorrhagic disorders are uncommon, occurring in 1 per 100 people, and are usually diagnosed in infants or young children, who often have relatives with similar symptoms. Congenital bleeding disorders lead to repeated hemorrhages that may be spontaneous or occur following minor injury or may occur in unexpected locations, such as joints, body cavities, retinal veins and arteries, or the central nervous system. Patients with mild congenital hemorrhagic disorders may have no symptoms until they reach adulthood or experience some physical challenge, such as trauma, dental extraction, or a surgical procedure. The most common congenital deficiencies are VWD, factor VIII and IX deficiencies (hemophilia A and B), and platelet function disorders. Inherited deficiencies of fibrinogen, prothrombin, and factors V, VII, X, XI, and XIII also exist, but are rare (Box 41-2). Far more patients have acquired bleeding disorders secondary to trauma, drug exposure, or chronic disease than have congenital or inherited coagulopathies. Chronic diseases or disorders commonly associated with bleeding are liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, and renal failure. In all cases, laboratory test results are necessary to confirm the diagnosis and guide the management of acquired hemorrhagic disorders.8 In North America, unintentional injury is the leading cause of death among those aged 1 to 45 years. The total rises when felonious, self-inflicted, and combat injuries are included: in the United States alone, trauma causes 93,000 deaths per year.9 Severe neurologic displacement accounts for 50% of deaths, with most occurring before the patient arrives at the hospital; however, of initial survivors, 20,000 die of hemorrhage within 48 hours.10 Acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock (ACOTS) accounts for fatal hemorrhage; 3000 to 4000 of these deaths are preventable. ACOTS is triggered by the combination of injury-related acute inflammation, platelet activation, tissue factor release, hypothermia, acidosis, and hypoperfusion (poor distribution of blood to tissues caused by low blood pressure), all of which are elements of systemic shock. For in-transit fluid resuscitation, colloid plasma expanders such as 5% dextrose are used to counter hypoperfusion.11 The administration of plasma expanders has a dilutional effect that is compounded by emergency department transfusion of RBCs, and although these measures are life saving, they intensify the coagulopathy, as does subsequent surgical intervention. Massive transfusion, defined as administration of 4 to 5 RBC units within 1 hour or 8 to 10 units within 24 hours, is essential in otherwise healthy trauma victims when the systolic blood pressure is less than 110 mm Hg, pulse is greater than 105 beats/min, pH is less than 7.25, hematocrit is less than 32%, hemoglobin is less than 10 g/dL, and PT is prolonged to greater than 1.5 times the mean of the reference interval or generates an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5.12 According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists surgical practice guidelines, RBC transfusions are required when the hemoglobin is less than 6.0 g/dL and are contraindicated when the hemoglobin is greater than 10.0 g/dL.13 For hemoglobin concentrations between 6.0 and 10.0 g/dL, the decision to transfuse is based upon the acuity of the patient’s condition as determined by physical evidence of blood loss; current blood loss rate; blood pressure; arterial blood gas values, especially pH and oxygen saturation; urine output; and laboratory evidence for coagulopathy, provided there is time for specimens to be collected and laboratory assays completed. During surgery, coagulopathy is assessed based on microvascular bleeding, which is evaluated by measuring the volume of blood filling suction canisters, surgical sponges, and surgical drains. Platelet concentrate is ordered when the platelet count is less than 50,000/mcL unless the surgeon anticipates limited blood loss. Platelet concentrate therapy is generally ineffective when the patient is known to have immune thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In patients with these conditions, therapeutic platelets are rapidly consumed, and their administration may therefore be contraindicated, although they may provide temporary rescue. Platelet concentrate is never ordered when the platelet count is greater than 100,000/mcL. Platelet administration may be necessary when the platelet count is between 50,000 and 100,000/mcL provided there is bleeding into a confined space such as the brain or eye; if the patient is taking aspirin or clopidogrel; if there is a known platelet disorder such as a release defect, Glanzmann thrombasthenia, or Bernard-Soulier syndrome (see Chapter 43); or if the surgery involves cardiopulmonary bypass, which suppresses platelet activity. Although many refer to frozen plasma as “fresh frozen plasma,“ this term no longer applies, because most FP is prepared up to 24 hours after the time of collection rather than within 8 hours, as was the traditional practice.14 High-volume trauma centers such as combat facilities may maintain a small inventory of thawed FP ready for administration. Thawed FP may be stored at 1° C to 6° C for up to 5 days subsequent to thawing. The activity of von Willebrand factor (VWF) and coagulation factors V and VIII decline to approximately 60% after 5 days of refrigerator storage; however, the product may still be transfused.15 Most trauma center transfusion service directors require surgeons and emergency department physicians to transfuse 1 unit of FP for every 4 units of RBCs, although there is battlefield evidence that a ratio of 1 unit of FP per single unit of RBCs may lead to more favorable mortality statistics.16 The latter approach places a strain on the FP supply, however. When administration of RBCs, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and FP fails to achieve hemostasis, activated prothrombin complex concentrate (FEIBA [factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity], Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, Ill.; Autoplex T, Nabi Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.), recombinant activated coagulation factor VII (NovoSeven), or the antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) may be employed. Autoplex T or FEIBA may be used at a dosage of 50 units/kg every 12 hours not to exceed 200 units/kg in 24 hours. The dose-response relationship of FEIBA is variable, and because FEIBA contains activated coagulation factors it raises the risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). NovoSeven has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in treating hemophilia A or B when factor VIII or factor IX inhibitors are present, respectively; its application in the treatment of ACOTS is off label. A NovoSeven dosage of 30 mcg/kg is instantly effective in stopping microvascular hemorrhage in nonhemophilic trauma victims, and NovoSeven does not cause DIC.17,18 However, one study found a possible link between off-label NovoSeven use and arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with existing thrombotic risk factors.19 Cyklokapron may be used at a loading dose of 1 g administered over 10 minutes followed by infusion of 1 g over 8 hours. First approved in 1986 to prevent bleeding in hemophilic patients who are about to undergo invasive procedures, Cyklokapron is effective for ACOTS, but this is an off-label use. Liver disease predominantly alters the production of the vitamin K–dependent factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X and control proteins C, S, and Z. In liver disease, these seven factors are produced in their des-γ-carboxyl forms, which cannot participate in coagulation (see Chapter 40). At the onset of liver disease, factor VII, which has the shortest plasma half-life at 6 hours, is the first coagulation factor to exhibit decreased activity. Because the PT is particularly sensitive to factor VII activity, it is characteristically prolonged in mild liver disease, serving as a sensitive early marker.20 Vitamin K deficiency caused by dietary insufficiency independent of liver disease produces a similar effect on the PT (see the case study in this chapter). Declining coagulation factor V activity is a more specific marker of liver disease than deficient factor II, VII, IX or X because factor V is non–vitamin K dependent and is not affected by dietary vitamin K deficiency. The factor V activity assay, performed in conjunction with the factor VII assay, may be used to distinguish liver disease from vitamin K deficiency.21 Fibrinogen is an acute phase reactant that is frequently elevated in early or mild liver disease. Moderately and severely diseased liver produces fibrinogen that is coated with excessive sialic acid, a condition called dysfibrinogenemia in which the fibrinogen functions poorly. Dysfibrinogenemia causes generalized soft tissue bleeding associated with a prolonged thrombin time and an exceptionally prolonged reptilase clotting time.22 In end-stage liver disease, the fibrinogen level may fall to less than 100 mg/dL, which is a mark of liver failure.23 VWF and factors VIII and XIII are acute phase reactants that may be unaffected or elevated in mild to moderate liver disease.24,25 In contrast to the other coagulation factors, VWF is produced from endothelial cells and megakaryocytes and is stored in endothelial cells and platelets. Moderate thrombocytopenia occurs in a third of patients with liver disease. Platelet counts of less than 150,000/mcL may result from sequestration and shortened platelet survival associated with portal hypertension and resultant hepatosplenomegaly. In alcoholism-related hepatic cirrhosis, acute alcohol toxicity also suppresses platelet production. Platelet aggregation and secretion properties are often suppressed; this is reflected in reduced platelet aggregometry and lumiaggregometry results. Occasionally platelets are hyperreactive. Aggregometry may be used to predict bleeding and thrombosis risk.26 Chronic or compensated DIC (see Chapter 42) is a significant complication of liver disease that is caused by decreased liver production of regulatory antithrombin, protein C, or protein S and by the release of activated procoagulants from degenerating liver cells. In addition, the failing liver cannot clear activated coagulation factors that are regularly produced by abdominal organs and transported through the portal circulation. In primary or metastatic liver cancer, hepatocytes also may produce procoagulant substances that trigger chronic DIC, leading to ischemic complications. In acute, uncompensated DIC, the PT, PTT, and thrombin time are prolonged; the fibrinogen level is reduced to less than 100 mg/dL; and fibrin degradation products, including D-dimers, are significantly increased.27 If the DIC is chronic and compensated, the only elevated test result may be the D-dimer assay value, a hallmark of unregulated coagulation and fibrinolysis.28 Although DIC can be resolved only by removing its underlying cause, its hemostatic deficiencies may be temporarily corrected by administering RBCs, FP, platelet concentrates, activated protein C, or antithrombin concentrates.29,30 The PT, PTT, thrombin time, fibrinogen concentration, platelet count, and D-dimer concentration are useful in characterizing the hemostatic abnormalities in liver disease (Table 41-2). Factor V and VII assays may be used in combination to differentiate liver disease from vitamin K deficiency. Both factors are decreased in liver disease, but only factor VII is decreased in vitamin K deficiency. TABLE 41-2 Hemostasis Laboratory Tests in Liver Disease Acute renal failure may be associated with acute gastrointestinal bleeding caused by specific anatomic lesions, but this does not necessarily indicate that a coagulopathy or platelet dysfunction is present.31 Chronic renal failure of any cause is commonly associated with platelet dysfunction and mild to moderate mucocutaneous bleeding.32 Platelet adhesion to blood vessels and platelet aggregation are suppressed, perhaps because the platelets are coated by guanidinosuccinic acid or dialyzable phenolic compounds.33 Decreased RBC mass (anemia) and thrombocytopenia contribute to the bleeding and may be corrected with dialysis, erythropoietin or RBC transfusions, and interleukin-11 therapy.34,35 Hemostasis activation syndromes that deposit fibrin in the renal microvasculature reduce the function of the glomeruli. Examples of such disorders are DIC, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Although these are by definition thrombotic disorders, they invariably cause thrombocytopenia, which may lead to mucocutaneous bleeding. Fibrin also may be deposited in renal transplant rejection and in the glomerulonephritis syndrome of systemic lupus erythematosus. This may be associated with a rise in quantitative plasma D-dimer, thrombin-antithrombin complexes, or prothrombin fragment 1 + 2, which are markers of coagulation activation (see Chapter 45).36 Laboratory tests for bleeding in renal disease provide only modest information with little predictive or management value. The bleeding time may be prolonged, but is too unreliable to provide an accurate diagnosis or to assist in monitoring treatment.37 Platelet aggregometry test results may predict bleeding. The PT and PTT are expected to be normal. Management of renal failure–related bleeding typically focuses on the severity of the hemorrhage without reliance on laboratory test results. Renal dialysis improves platelet function, particularly when anemia is well controlled. Desmopressin acetate may be administered intravenously (DDAVP) or intranasally (Stimate) to increase the plasma concentration of high-molecular-weight multimers of VWF, which also aids platelet adhesion and aggregation.38 Patients with renal failure should not take aspirin, clopidogrel, or other platelet inhibitors, because these drugs increase the risk of hemorrhage. Nephrotic syndrome is a state of increased glomerular permeability associated with a variety of conditions, such as chronic glomerulonephritis, diabetic glomerulosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, amyloidosis, and renal vein thrombosis.39 In nephrotic syndrome, low-molecular-weight proteins are lost through the glomerulus into the glomerular filtrate and the urine. Coagulation factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, X and XII have been detected in the urine, as have the coagulation regulatory proteins antithrombin and protein C. In 25% of cases, loss of regulatory proteins takes precedence over loss of procoagulants and leads to a tendency toward venous thrombosis.40 Because of their sterile intestines and the minimal concentration of vitamin K in human milk, newborns are constitutionally vitamin K deficient.41 Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn was common in the United States before routine administration of vitamin K to infants was legislated in the 1960s, and it still occurs in developing countries. The activity levels of factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X are lower in normal newborns than in adults, and premature infants have even lower concentrations of these factors.42 Breastfeeding prolongs the deficiency, because passively acquired maternal antibodies delay the establishment of gut flora. The γ-carboxylation cycle of coagulation factors is interrupted by coumarin-type oral anticoagulants such as warfarin that disrupt the vitamin K epoxide reductase and vitamin K quinone reductase reactions (Figure 41-1). In deficient γ-carboxylation, the liver releases dysfunctional des-γ-carboxyl factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X, and proteins C, S, and Z; these inactive forms are called proteins in vitamin K antagonism (PIVKA). Therapeutic overdose or the accidental or felonious administration of warfarin-containing rat poisons may result in moderate to severe hemorrhage because of the lack of functional factors. The effect of brodifacoum or “superwarfarin,“ often used as a rodenticide, lasts for weeks to months, and treatment of poisoning with this substance requires repeated administration of vitamin K with follow-up PT monitoring.43 Warfarin overdose is the single most common reason for hemorrhage-associated emergency department visits. Acquired autoantibodies that specifically inhibit factors II (prothrombin), V, VIII, IX, and XIII and VWF have been described in nonhemophilic patients.44 Anti-VIII is the most common. Patients who develop an autoantibody to factor VIII, which is diagnostic of acquired hemophilia, are frequently older than age 60 and have no apparent underlying disease. Acquired hemophilia is occasionally associated with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, or lymphoproliferative disease. It also may occur in women of childbearing age 2 to 5 months after delivery. Patients with inhibitor autoantibodies are given immunosuppressive therapy, although autoantibodies that develop after pregnancy typically disappear spontaneously. Acquired hemophilia has an overall incidence of 1 per 1 million people per year. Patients experience sudden and severe bleeding in soft tissues or bleeding in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract. Acquired hemophilia, even when treated, remains fatal in at least 20% of cases. Autoantibodies to other procoagulants are less frequent, but create similar symptoms.45 The in vitro kinetics of factor VIII neutralization by inhibitor are nonlinear. Although there is early rapid loss of factor VIII activity, residual activity remains, which indicates that the reaction has reached equilibrium. This is called type II kinetics (Figure 41-2). In contrast, alloantibodies to factor VIII, which develop in 20% to 25% of patients with severe hemophilia in response to factor VIII therapy, exhibit type I kinetics. In the latter, there is linear in vitro neutralization of factor VIII activity over 1 to 2 hours, which results in complete inactivation. In type I kinetics in vitro measurement is relatively accurate, whereas in type II kinetics the titration of inhibitor activity is semiquantitative.46

Hemorrhagic Coagulation Disorders

Symptoms of Coagulopathies

Mucocutaneous versus Anatomic Hemorrhage

Acquired versus Congenital Bleeding Disorders

Test

Assesses for

Hemoglobin, hematocrit, reticulocyte count

Anemia associated with chronic bleeding; bone marrow response

Platelet count

Thrombocytopenia

PT

Deficiencies of factors II (prothrombin), V, VII, or X (clotting time prolonged)

PTT

Deficiencies of all factors except VII and XIII (clotting time prolonged)

Thrombin time

Hypofibrinogenemia and dysfibrinogenemia

Acquired Coagulopathies

Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock

Management of Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock

Use of Frozen Plasma in Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock

Use of Activated Prothrombin Complex Concentrate, Recombinant Activated Factor VII, and Tranexamic Acid in Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock

Liver Disease

Procoagulant Deficiency in Liver Disease

Platelet Abnormalities in Liver Disease

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Liver Disease

Hemostasis Laboratory Tests in Liver Disease

Assay

Interpretation

Fibrinogen

>400 mg/dL in early, mild liver disease; <200 mg/dL in moderate to severe liver disease causing hypofibrinogenemia or dysfibrinogenemia

Thrombin time

Prolonged in dysfibrinogenemia, hypofibrinogenemia, elevation of fibrin degradation products, and therapy with unfractionated heparin

Reptilase time

Prolonged in hypofibrinogenemia, significantly prolonged in dysfibrinogenemia; assay rarely used

PT

Prolonged even in mild liver disease due to presence of des-γ-carboxyl factors in place of normal factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X. Report PT in seconds, not INR, when testing for liver disease.

PTT

Mildly prolonged in severe liver disease due to DIC or des-γ-carboxyl factors II (prothrombin), IX, and X

Platelet count

Mild thrombocytopenia, platelet count <150,000/mcL

Platelet aggregometry

Mild suppression of platelet aggregation and secretion to most agonists

D-dimer

>240 ng/mL by quantitative assay

Euglobulin clot lysis time

Lysis in <2 hr in primary or secondary systemic fibrinolysis; assay rarely used

Renal Failure and Hemorrhage

Nephrotic Syndrome and Hemorrhage

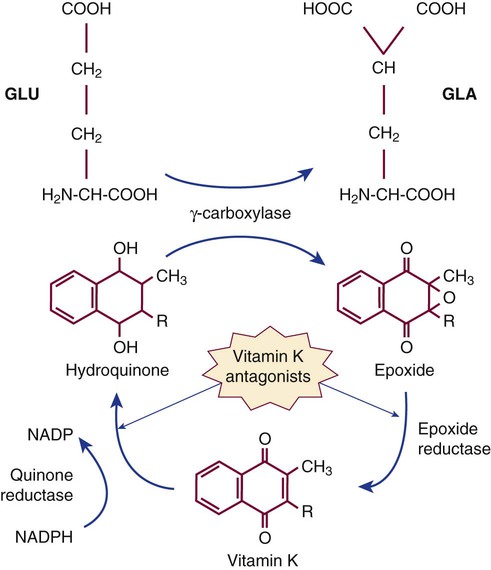

Vitamin K Deficiency

Hemorrhagic Disease of the Newborn Caused by Vitamin K Deficiency

Vitamin K Antagonists

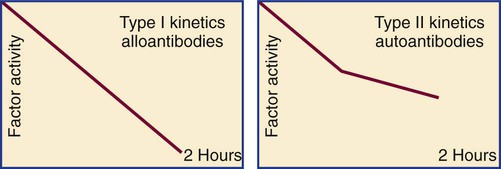

Autoanti-VIII Inhibitor and Acquired Hemophilia

Clot-Based Studies in Acquired Hemophilia