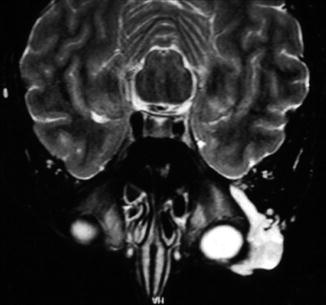

Fig. 40.1

Percutaneous sclerotherapy in a facial congenital vascular malformation

It is very useful to perform a preoperative angiography before injecting the sclerosing agent. Contrast material is injected and imaging performed to confirm that the needle is within the lesion, to well evaluate the size of the malformation and to ensure that there is no extravasation into normal tissues. The contrast material in the abnormal vascular pool is then aspirated through the needle, to limit the dilution of the sclerosant. The volume of contrast material required to fill the space is then used to estimate the quantity of sclerosant needed.

Scleroembolization is preferably assisted by fluoroscopic guidance, injecting the sclerosing agent mixed with a contrast medium to control its spread within the vessels. Furthermore, it is advisable to perform the puncture of the lesion from multiple accesses and inject small doses of sclerosing agent at each point, in order to reduce the risk of local complications. The sclerosing agent should be slowly injected until the abnormal vascular structure is filled.

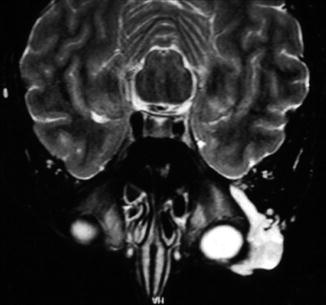

Simultaneous external compression, manual or mechanic, may also be required to occlude outflow vessels. Compression is recommendable especially in juxta-ocular lesions (Fig. 40.2), to avoid the risk of propagation of the sclerosant in the retinal vessels.

Fig. 40.2

Juxta-ocular venous malformation

In the CVMs located in close proximity of the upper airway, it is highly recommended to perform a preoperative tracheostomy, to prevent the risk of asphyxiation from edema post-sclerosis and airway occlusion (Fig. 40.3).

Fig. 40.3

Preoperative tracheostomy in a congenital vascular malformation involving the upper airways

Various sclerosing agents have been used in the treatment of CVMs of the neck and face, including sodium tetradecyl sulfate, polidocanol, morrhuate sodium, ethanolamine oleate, and ethibloc.

The foam of sodium tetradecyl sulfate or polidocanol has been proposed for VMs extended through or very close to the skin or mucous membranes, in order to reduce the risk of necrosis and ulceration.

In the LMs of the head and neck, both in microcystic and macrocystic forms, OK-432, bleomycin, doxycycline, and pingyangmycin are the more widely used sclerosants.

In craniofacial AVMs N-butyl-cyanoacrylate and ethylene-vinyl-alcohol copolymer have been proposed for preoperative scleroembolization, to achieve a more easily surgical excision.

Absolute ethanol is certainly the most effective and the most commonly used sclero-agent for all the types of cervicofacial CVMs, both low flow and high flow [5, 6]. In fact ethanol is the only sclerosant which is able to induce denaturation of tissue protein and to avoid regeneration of endothelial cells with subsequent permanent obliteration of the vessel lumen. The worst aspect of ethanol is its extremely dangerous toxicity, which induces a significant morbidity rate that is particularly high in CVMs located in the facial region. In most situations ethanol is injected in its dehydrated form (>98 % pure). The total amount used depends on the location and extent of the CVM lesion. Anyway it must not exceed the maximum allowable amount (1 mL/kg of body weight), to minimize its toxicity.

A multistaged treatment strategy is mandatory to obtain the best results minimizing the risks: it is possible to repeat the sclerosant treatment to the recurrent and incompletely controlled lesion as necessary.

Complications

Many adverse events are described after sclerotherapy of head and neck CVMs [7].

Usual collateral effects are pain, swelling, and hyperemia at the injection sites. These signs and symptoms are very discomforting and troublesome in the area of the face, resulting in significant cosmetic disorders. Anyway they are transient, usually peaking at 48–72 h, and well controlled with oral steroids and nonnarcotic analgesics administered for a few days.

The skin or mucosal damage is a frequent adverse event of the sclerosing treatment of the head and neck CVMs. The lesions located in close proximity to the facial skin or oral mucosa (Fig. 40.4) carry a significant risk of ulceration. The risk of necrosis is particularly high for the lesions of the tongue, lip, and gum. Most of the acute lesions are simple erythema or vesicles confined to the skin or mucosa. Sometimes there is an involvement of the subcutaneous tissue with development of necrosis and ulcers. Most of these lesions heal spontaneously with or without minimal wound disposition or debridement.