Ovarian Carcinoma

Though not the most common gynecologic malignancy, epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal, affecting approximately 26,000 women per year and causing at least 15,000 deaths in the United States, representing the fifth most frequent cause of cancer death in women ( ). The median age of diagnosis is 63, and close to 50% of patients are 65 years of age or older. The risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer include nulliparity, whereas protective factors include multiple births and use of oral contraceptives. Family history of ovarian cancer is an important risk factor, and compared with the general population, whose lifetime risk is 1.6%, a woman with a single relative affected by ovarian cancer has a 4% to 5% increased risk for developing ovarian cancer. Genes implicated in increased susceptibility if germ-line inheritance occurs in an autosomal-dominant pattern include the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (hereditary breast-ovarian cancer), and mismatch repair genes such as MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, and PMS2 (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal syndrome). For women carrying a mutated high-risk gene, parity lowers risk but protective use of oral contraception remains controversial.

HISTOLOGY

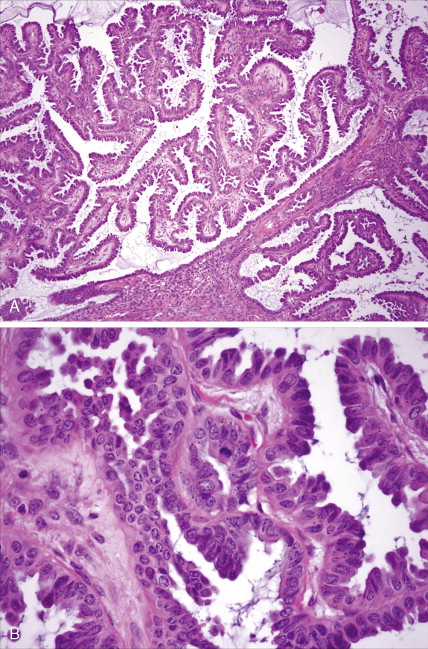

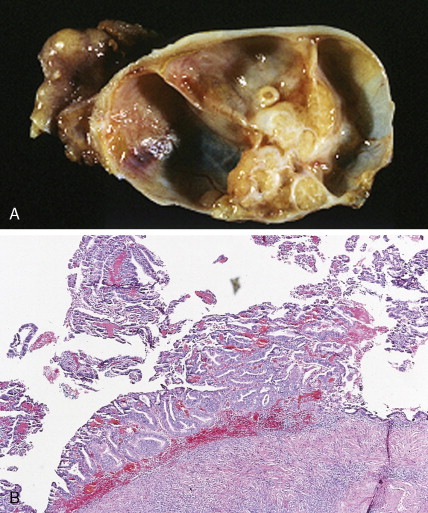

The majority of malignant ovarian tumors are of epithelial origin ( Table 9.1 ). Papillary serous adenocarcinomas, which constitute the majority of these tumors, are classically characterized by papillary fronds and psammoma bodies with cells reminiscent of fallopian tube mucosa. However, because most papillary serous carcinomas are poorly differentiated, architectural changes often include a more solid growth pattern with slitlike spaces and high-grade cytology. The contralateral ovary is involved either grossly or microscopically in at least half of cases. Endometrioid tumors are second in frequency and are less commonly bilateral but may coexist with a synchronous uterine carcinoma in up to 20% of cases. The remaining ovarian epithelial malignancies—mucinous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and malignant Brenner tumors—are all less common. Mixed histologies may occur in the same patient, and squamous differentiation may be present in endometrioid tumors.

| Tumor | Frequency(%) |

|---|---|

| Epithelial | |

| Papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma | 38 |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 11 |

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 13 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 5 |

| Malignant Brenner tumor | <0.5 |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 15 |

| Sex Cord–Stromal | |

| Granulosa cell tumor | 2 |

| Sertoli-Leydig tumor | <1 |

| Mixed tumors | <0.5 |

| Germ Cell | |

| Immature teratoma | <0.5 |

| Embryonal carcinoma | <0.5 |

| Endodermal sinus tumor | <1 |

| Choriocarcinoma | <0.5 |

| Mixed | <1 |

| Dysgerminoma | 2 |

| Stromal | |

| Sarcomas | <0.5 |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 10 |

| Lymphoma | <0.5 |

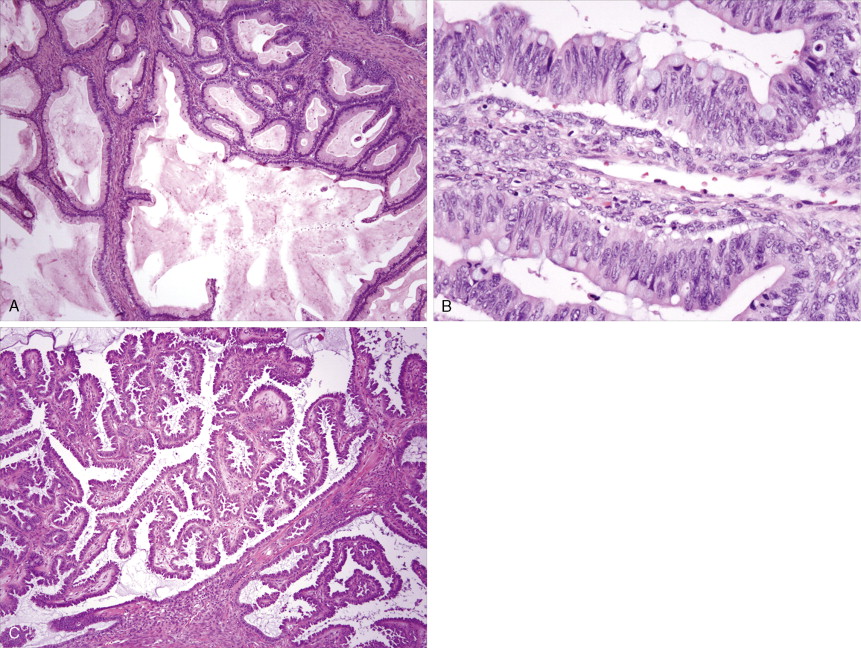

With the exception of the poor prognosis associated with advanced clear cell tumors, multivariate analyses have generally not shown histologic subtype to influence survival when comparing stage for stage. Instead the grade of tumor contributes more significantly to prognosis, with shorter survival times associated with high-grade tumors. Poorly differentiated carcinomas are usually more chemotherapy-sensitive than lower grade tumors. Borderline epithelial tumors consist of neoplasms with a complex architecture that traditionally show no evidence of stromal invasion; however, occasionally borderline tumors can be associated with microinvasion of the underlying stroma, a finding that does not significantly affect outcome ( ; Hart, 2005). Approximately 90% of borderline tumors are serous and 10% are mucinous; rarely, endometrioid and clear cell varieties are encountered. Patients who carry a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene typically have an improved overall prognosis as compared with patients who do not carry a such a mutation. Borderline tumors have a very long natural history, although they can metastasize and cause death ( ). Poorer prognosis is most frequently associated with the presence of micropapillary features and/or invasive implants (noninvasive implants do not affect survival rates) ( ).

Germ cell tumors constitute approximately 20% of benign ovarian neoplasms but represent <5% of ovarian malignancies ( ). They are most common in young women and children, where cure and preservation of fertility are frequently achieved. Mature teratoma, a benign neoplasm, is the most common germ cell tumor of the ovary. Dysgerminoma accounts for nearly half of all malignant germ cell tumors, with a median age at diagnosis of 22 years. Other malignant germ cell tumors include immature teratoma, yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, and nongestational choriocarcinoma. The malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are all rare but interesting because of their similarity to male testicular cancers in both natural history and responsiveness to chemotherapy.

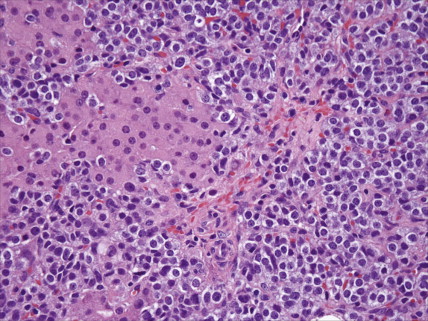

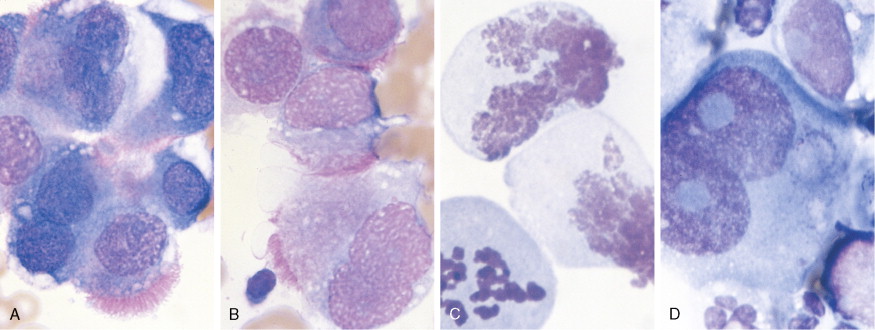

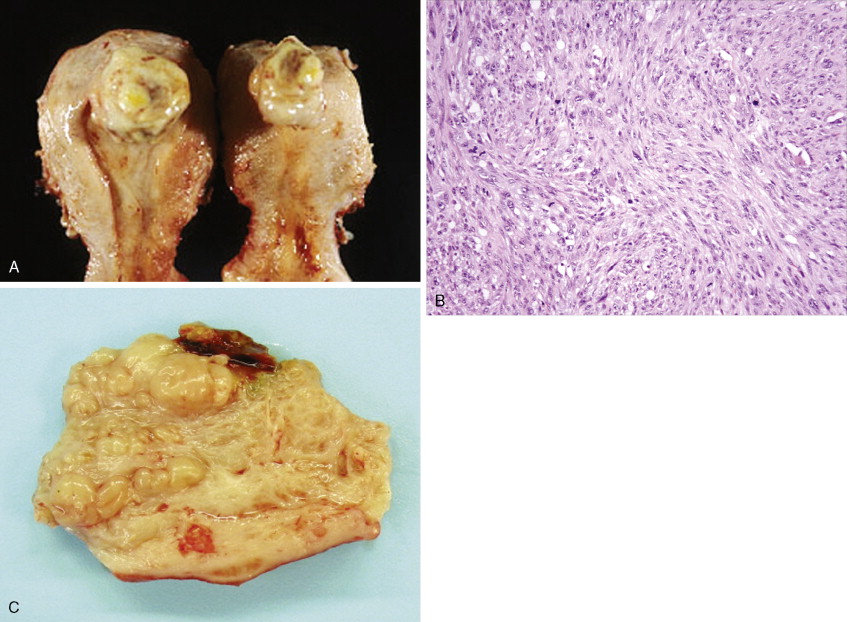

Other nonepithelial ovarian tumors may be divided into sex cord–stromal tumors ( ), metastatic malignancies ( ), and sarcomas ( ). Of the sex cord–stromal tumors, granulosa cell tumors are the most common and constitute 2% of all ovarian malignancies. Composed of granulosa cells with or without theca cells, they may be hormonally active, causing resumption of menses in older women or precocious pseudopuberty in the rare young person developing this malignancy. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are sex cord–stromal tumors marked by some testicular differentiation and often by androgen production; they are rarely malignant. Metastatic tumors, which represent 10% of ovarian malignancies, most commonly originate from primary sites in the endometrium/cervix, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and breast. They include Krukenberg tumors of gastric origin, which exhibit a classic mucus-secreting, “signet-ring” cell, metastatic colon carcinomas which often demonstrate characteristic dirty necrosis, and pancreatic carcinomas, which not infrequently mimic a primary ovarian mucinous tumor. Metastases from the appendix can pose a diagnostic challenge, in that the primary tumor may be occult and morphologic features of appendiceal and ovarian neoplasms can be identical. Epithelial neoplasms in the ovary associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei should be considered of appendiceal origin until proven otherwise ( ). Immunohistochemical stains can be useful in separating primary and secondary tumors of the ovary (Hart 2005). Primary ovarian sarcomas are very rare and may be classified in a manner similar to that used for uterine sarcomas. The most common sarcomas primary to the ovary include leiomyosarcoma (LMS) ( ), endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) ( ) and fibrosarcoma ( ); metastases from the uterus should always be considered for LMS and ESS. Mixed tumors marked by the presence of both sarcomatous and epithelial elements also occur, and are termed carcinosarcomas (previously called malignant mixed müllerian tumors).

Three types of small cell carcinoma, all with morphologic overlap, can occur in the ovary: (1) small cell carcinoma, pulmonary type; (2) small cell carcinoma, hypercalcemic type; and (3) metastatic small cell (neuroendocrine) carcinomas to the ovary, typically from the cervix, lung, or GI tract. Distinction of primary versus secondary small cell carcinoma can be determined with the aid of ancillary studies, such as immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, in the majority of cases ( ).Small cell carcinomas of the ovary are typically very aggressive and have a poor prognosis.

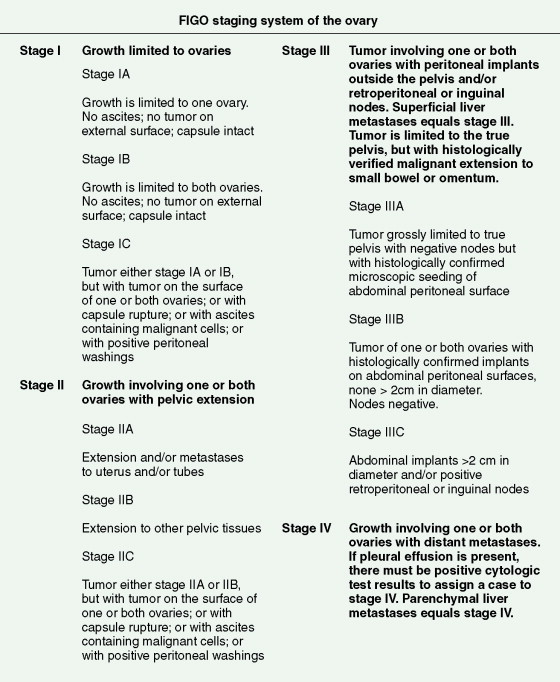

STAGING OF OVARIAN CARCINOMA

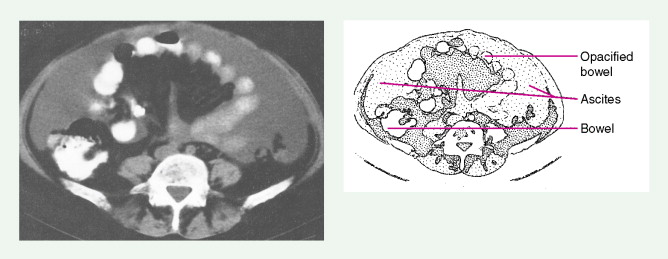

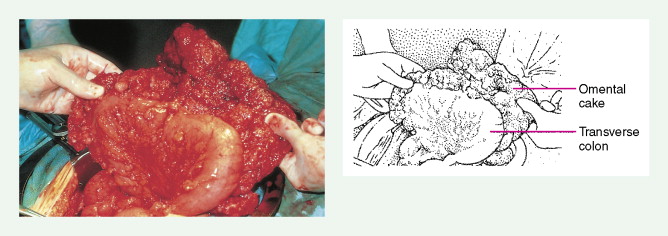

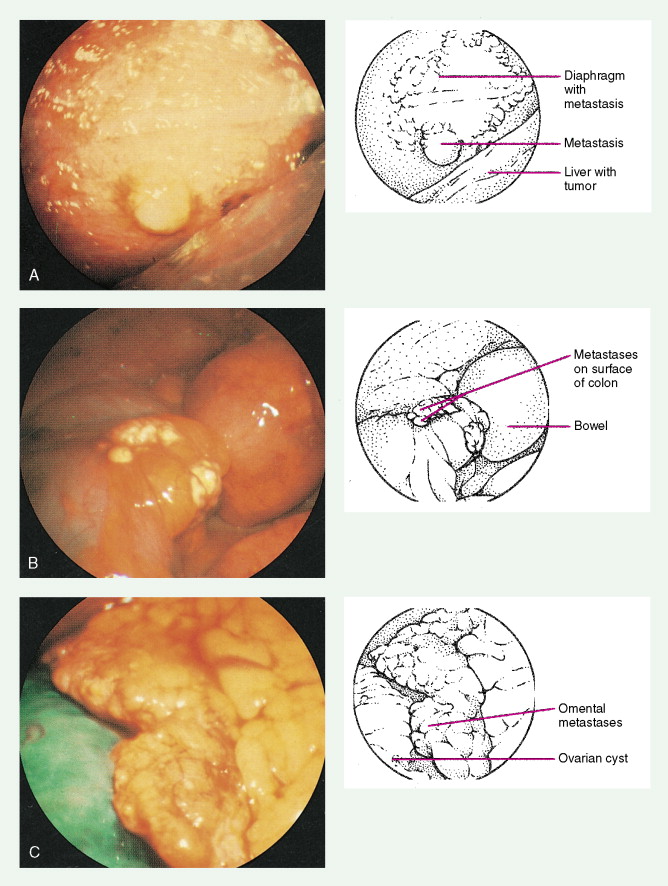

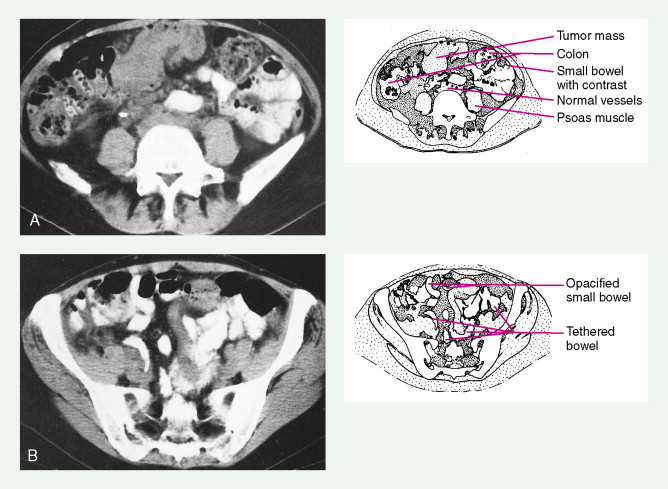

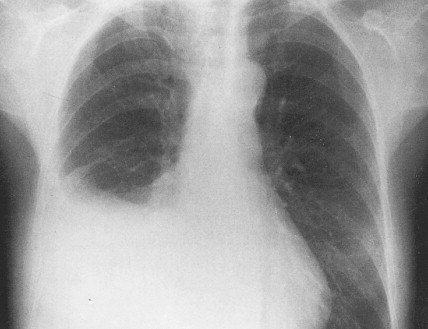

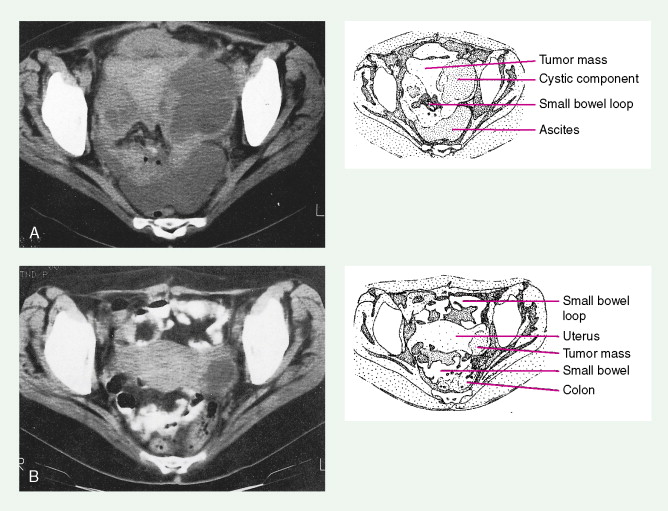

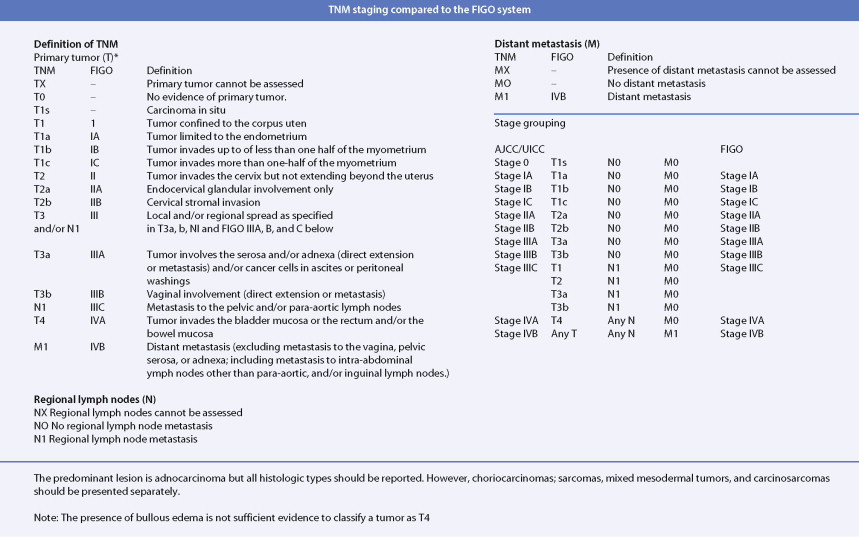

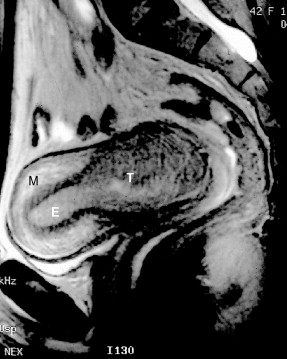

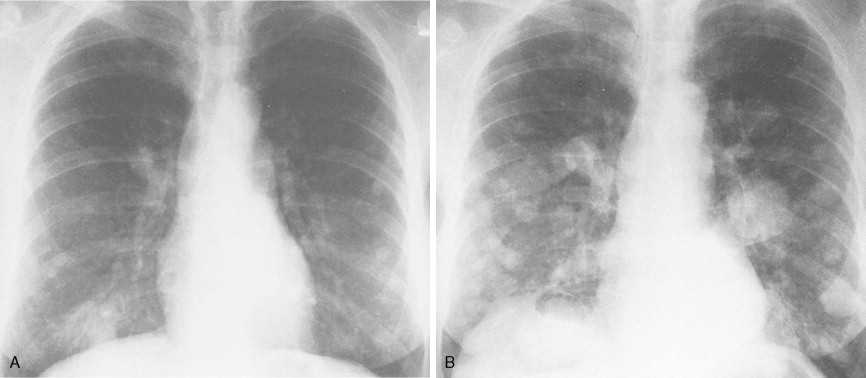

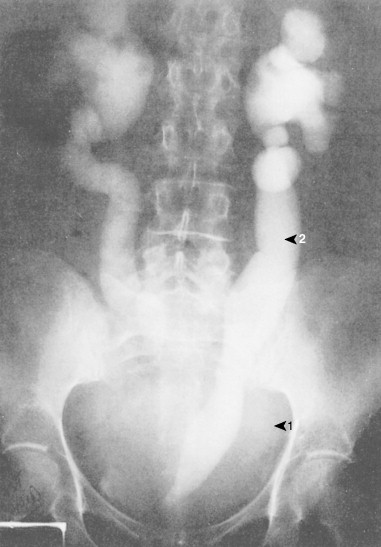

Ovarian cancer is staged according to FIGO staging. * Early-stage ovarian carcinoma is confined to the ovary (stage I) or the pelvic organs (stage II) (see Fig. 9.1 ). However, because of the vague nature of symptoms and the lack of effective screening programs, most women present with spread throughout the peritoneal cavity (stage III). Ovarian carcinomas usually disseminate intraperitoneally. Extraperitoneal dissemination (stage IV) is less common and usually occurs late in the course of the disease, whereas pleural effusions are the most common manifestation of extra-abdominal disease. Although the mechanism for this tendency is unclear, the right hemidiaphragm is commonly involved in stage IV disease, and there are connections between the lymphatic systems above and below the diaphragm. Parenchymal lung involvement is unusual. Nodal spread may also occur to Virchow’s node (supraclavicular), the inguinal nodes or Sister Mary-Joseph’s node in the para-umbilical region. The FIGO staging system requires assessment of the ovarian capsule, lymph node dissection, and multiple peritoneal/omental biopsies for accurate staging. Without careful surgical evaluation, up to 30% of women may have their disease under-staged.

* The revised FIGO staging is just being released ( ).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Early-stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma rarely causes symptoms, although large masses may cause pelvic pain, constipation, tenesmus, and urinary frequency or dysuria. Abdominal cramping, flatulence, bloating, and gas pains are more common presenting symptoms, usually due to tumor dissemination throughout the peritoneal cavity. These symptoms unfortunately are often poorly defined and occasionally mild; they may be attributed to benign GI pathology, until the woman has obvious abdominal distention, most often related to increasing ascites or intestinal obstruction. The importance of a pelvic examination in the initial evaluation of any woman with GI complaints cannot be overemphasized. Late in the course of the disease, shortness of breath from pleural effusions may occur. Hematogenous dissemination to the liver, lungs, and left supraclavicular or axillary nodes is a less common occurrence, and bone, brain, or meningeal metastases are rare. However, unusual metastases may occur, especially in patients with a prolonged natural history.

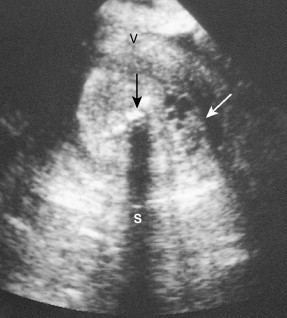

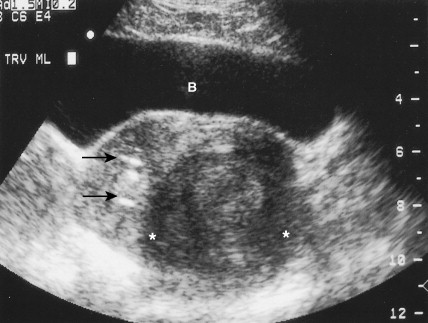

In women with an abnormal pelvic mass, useful diagnostic tests include a transvaginal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scan. The CA125 blood test (which measures the concentration of a blood protein known as cancer antigen 125) is not a useful screening tool but is important in monitoring the results of therapy once a diagnosis has been established and thereafter following for recurrence once the patient has completed chemotherapy.

Nonepithelial tumors often present in a fashion similar to epithelial malignancies. Granulosa cell tumors and other stromal neoplasms are usually detected when a woman presents with pelvic discomfort or vague abdominal symptoms; these tumors also may secrete estrogen and cause resumption of menses in the postmenopausal woman; these tumors can also produce inhibin, which can serve as a biomarker. This hyperestrogenic effect may lead to the simultaneous development of endometrial carcinoma. Germ cell tumors are seen almost exclusively in premenopausal women. They are occasionally detected as an asymptomatic pelvic mass, but more commonly they present acutely with symptoms of rapid tumor growth or as abdominal emergencies secondary to hemorrhage, rupture, or torsion.

Endometrial Carcinoma

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the female genital tract, with up to 40,000 new cases diagnosed each year ( ). Despite its prevalence, less than one sixth of these cases (~7000) result in death from disease. Increased survival rates are most likely secondary to patient and physician education, the presence of symptoms at earlier stages of the disease, and ease of obtaining a biopsy specimen. Therefore, cases are diagnosed at an earlier stage than in the past, and death rates are continuing to decrease. The incidence of endometrial cancer peaks late in the sixth decade, and proven associations include obesity (50 pounds overweight increases the risk 10-fold), diabetes mellitus, late menopause, and probably hypertension, as well as other factors such as nulliparity and infertility, which increase estrogenic stimulation to the endometrium. Exogenous estrogens increase the risk for carcinoma, but this can be reversed by cycling estrogens with progestins. Polycystic ovarian disease and other illnesses that cause chronic anovulation increase the risk for this malignancy, and women with these problems may develop endometrial carcinoma before menopause. Sporadic cases of endometrial carcinomas have been shown to be associated with multiple gene mutations, including TP53 mutations in serous (type II) carcinomas, and PTEN , KRAS , and β-catenin mutations in endometrioid (type II) carcinomas ( ). Endometrial carcinomas associated with mutations in the mismatch repair genes MSH2 and MLSH1 can be a sporadic findings but is more commonly associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome. Patients known to be affected by HNPCC have an increased risk for developing endometrial carcinoma (as well as colorectal carcinoma) at a younger age; however, there is controversy as to whether the gene mutations affect prognosis ( ).

There is no effective screening method for detecting endometrial carcinoma. However, on occasion an endometrial cancer may be revealed when malignant or normal endometrial cells are seen in a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear. The presence of the former requires distinction between endocervical and endometrial origins, and the presence of the latter may indicate a carcinoma in approximately 10% of postmenopausal women. Nevertheless, evaluation in these women, as well as in women with postmenopausal bleeding, requires endometrial sampling or dilatation and curettage. The majority of women with well-differentiated stage I endometrial cancers are cured by surgery alone. Radiation therapy and/or more commonly vaginal brachytherapy are being used for higher risk patients (i.e., significant myometrial involvement, high-grade tumors, cervical involvement with cancer) so as to decrease pelvic and vaginal recurrences.

HISTOLOGY

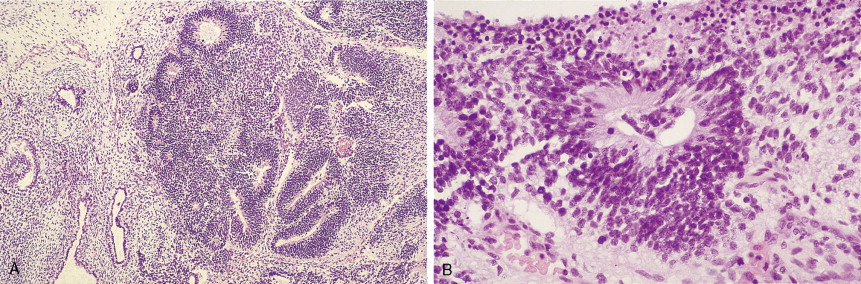

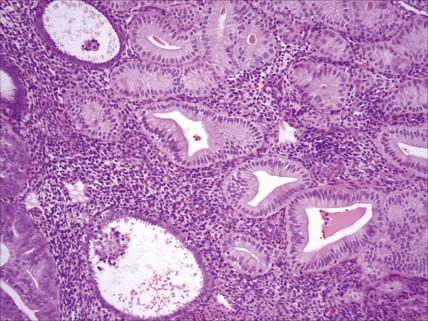

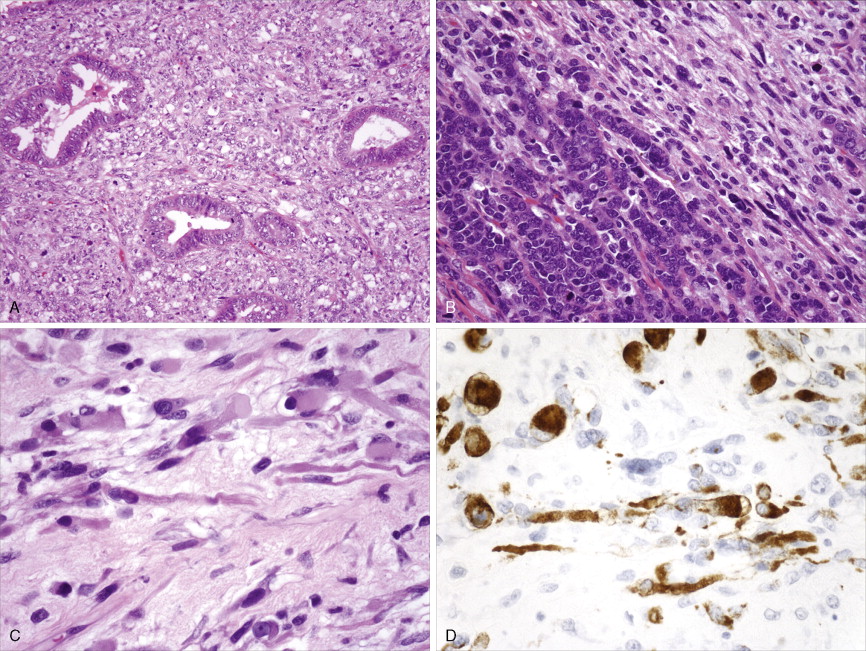

Adenocarcinoma constitutes more than 90% of endometrial cancers, with the endometrioid subtype being the most common. Other subtypes of endometrial carcinoma include serous, mucinous, clear cell, and mixed subtypes. Grossly, these tumors are often polypoid or exophytic; however, a more endophytic invasive growth pattern can also be recognized. The microscopic appearance is marked by architectural irregularity with multiple fused and/or cribriform glands that crowd out supporting stroma, and it is not infrequently associated with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN), the endometrioid carcinoma precursor lesion. The cells in an endometrioid carcinoma are more frequently of lower grade, but increased cytologic atypia and pleomorphism can be encountered. Tumor grade, which takes into account cell type, nuclear atypia, and glandular to more solid growth patterns, seems to be an important prognostic feature; lymphatic and vascular space involvement may also be significant for prognosis. In contrast to endometrioid and mucinous carcinomas, which are graded on the basis of architectural features, grade of serous and clear cell carcinomas is based on cytologic findings. Squamous, and less frequently mucinous, differentiation can be seen, especially in endometrioid subtypes. Papillary serous and clear cell adenocarcinomas of the uterus (type II endometrial cancers) are seen less frequently when compared with endometrioid carcinomas, and are highly aggressive types of endometrial cancer. Treatment of early papillary serous and clear cell tumors is controversial. Unlike endometrioid and mucinous carcinomas, noninvasive serous and clear cell carcinomas of the uterus still have a poor prognosis.

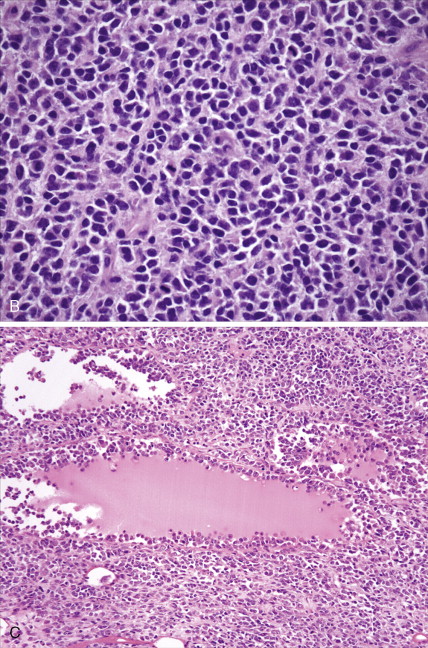

Sarcomas, of which leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the most common, represent approximately 5% of uterine malignancies. Believed to arise de novo and not from leiomyomas, LMSs usually occur in the fifth and sixth decades. They are homologous tumors, containing elements derived from uterine smooth muscle, and are usually intramural in location. Microscopically they are composed of atypical spindle cells associated with necrosis and increased mitotic activity, often with 10 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs). A variant showing 5–10 mitoses per 10 HPFs is of uncertain malignant potential (called a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential, or “STUMP”) and may possess a long natural history. A diagnosis of STUMP should be made with caution in a myomectomy specimen, because evaluations may be limited. Extrauterine involvement has been seen with both benign and malignant smooth muscle neoplasms: the former is associated with disseminated peritoneal leiomyomatosis, intravascular leiomyomatosis, or benign metastasizing leiomyoma; metastatic spread of LMS connotes a poor prognosis.

Endometrial stromal tumors are homologous tumors, derived from uterine mesenchyme, which resemble proliferative endometrial stroma, demonstrate little cytologic atypia, contain prominent spiral-like arterioles, and have variable numbers of mitotic figures (most frequently fewer than 10 per 10 HPFs). Well-circumscribed stromal neoplasms are termed endometrial stromal nodules, whereas those that infiltrate the myometrium and often demonstrate vascular invasion are termed endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESSs) (previously called endolymphatic stromal myosis or low-grade ESS). Endometrial stromal nodules are benign lesions, whereas ESSs are considered low-grade tumors that have an indolent clinical course and may take up to 10 or so years to recur. ESSs usually have a low mitotic count (<10 per 10 HPFs) and an absence of necrosis. High-grade malignancies that are thought to be of endometrial stromal origin but no longer resemble endometrial stroma are termed undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUSs) (previously called high-grade ESSs). UUSs are associated with a greater degree of nuclear atypia and pleomorphism, extensive necrosis, and numerous mitotic figures (often >10, and frequently as many as 20 mitoses per 10 HPFs including atypical forms). Heterologous tumors, which are extremely rare, are most frequently associated with an epithelial component (carcinosarcomas, see below).

Carcinosarcomas (previously called malignant mixed müllerian tumors) contain both epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) elements. The epithelial component is most commonly high grade, whereas the sarcomatous portion may be homologous or heterologous (most frequently rhabdomyosarcoma). Carcinosarcomas have a poorer prognosis compared with endometrioid cancers, stage for stage.

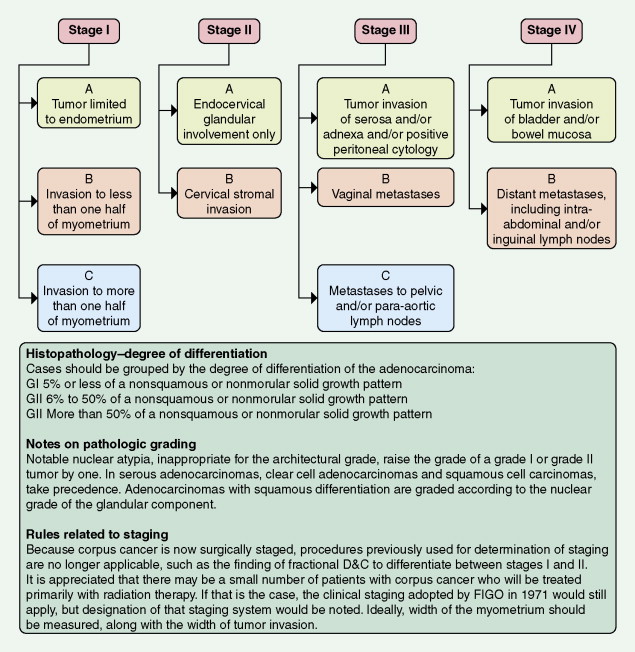

STAGING OF ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA

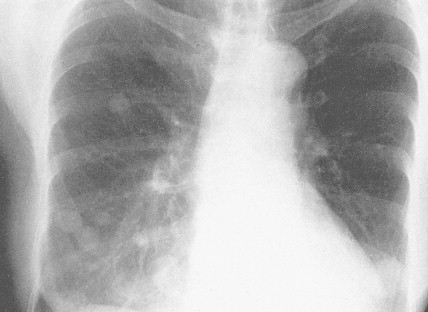

Most endometrial malignancies are confined to the uterus at the time of diagnosis (stage I) (see Fig. 9.34 ). Spread to the cervix marks stage II tumors and should be described as spread to cervical mucosa (stage IIa) and/or cervical stromal (stage IIb). More advanced stages—which include spread to pelvic organs or retroperitoneal lymph nodes (stage III) or hematogenous spread to distant sites (stage IV), usually to the lungs—are occasionally seen; such cases have a worse prognosis.

Preoperative workup in patients with suspected higher risk endometrial cancer would include a chest CT scan to rule out lung metastases and an abdominal/pelvic CT scan to rule out liver, nodal, and other sites of metastases. Depth of invasion of the myometrium as assessed at surgery also is essential for staging. Removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes is typically recommended for patients with high-risk cancers and can help decide treatment after surgery. These factors provide useful information for determining prognosis and aid in the choice of possible adjuvant therapy.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

More than 90% of women with endometrial carcinoma present with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Although atrophic vaginitis is the most common cause of vaginal bleeding in low-risk postmenopausal women, patients presenting with this complaint require an endometrial biopsy for proper evaluation. With increasing age, abnormal postmenopausal bleeding is more often associated with carcinoma; overall, about 20% of such women will be found to have a malignancy. Carcinoma in perimenopausal women or anovulatory women may present with heavy or prolonged bleeding; these women may ignore changes in their bleeding pattern, considering them to be signs of approaching menopause. If the tumor spreads outside the uterus, adjacent organs are most commonly involved. Vaginal or suburethral metastases may cause pain, bleeding, or discharge; abdominal distention, and bowel or urinary dysfunction may develop from involvement of the bladder or rectum. Back pain may result from para-aortic nodal involvement. Pulmonary metastases may occur late in the course of disease as a result of hematogenous spread, and brain metastases may occur, but less commonly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree