Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Min En Nga

Amitabh Srivastava

INTRODUCTION

The predominant mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract, until recently, was believed to be of smooth muscle origin. However, it was well recognized that these gastrointestinal “smooth muscle tumors” were quite distinct from their soft tissue counterparts. In 1941, Stout and Golden recognized that in the gastrointestinal tract it was impossible to “be entirely certain that any leiomyoma is necessarily benign, except the small intramural tumors, which are chance findings at autopsy or operation.”1 In a later publication, focusing on the epithelioid variant of these tumors, Stout reported that most gastric tumors behaved in a benign fashion but that some displayed malignant behavior and even the ability to metastasize. The propensity for malignant behavior, he indicated, “cannot be recognized by any clinical or gross characteristics” but may be suspected if the tumor showed an “elevated mitotic count in 50 high power fields(hpf).”2 This uncertainty in predicting malignant behavior led to the use of terms such as “malignant leiomyoma” and “leiomyoblastoma” to describe these tumors.

The purported smooth muscle origin of these tumors became questioned when immunohistochemistry came into widespread use. These tumors were found to be largely devoid of conventional markers of smooth muscle differentiation.3,4 Moreover, a subset was also found to express neural markers. In 1983, Mazur and Clark proposed the term “stromal tumor” for these unique neoplasms, reflecting the uncertainty regarding their line of differentiation.5 In the early 1990s, CD34 emerged as the first relatively specific marker for these stromal tumors and similarities between these tumors and the interstitial cells of Cajal were recognized soon thereafter by multiple groups.6, 7 and 8 This explained the mixed smooth muscle—neural phenotype of these lesions. The designation of “gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor,”7 however, did not gain acceptance and the term “gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)” came into widespread use. Tumors previously classified as gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors were also accepted as variants of GISTs.9

In their seminal discovery in 1998, Hirota et al. reported that the majority of GISTs had activating mutations in the KIT gene and also expressed the KIT protein on immunohistochemistry.10 A subset of KIT-negative GISTs were later found to harbor mutations in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFR-a), another receptor tyrosine kinase closely related to KIT.11 Treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) led to marked improvement in outcome of these previously treatment refractory tumors12,13 and this heralded an era of unprecedented developments in molecular targeted therapy. GISTs have now become a model for molecular targeted therapy of solid tumors.

CLINICAL FEATURES

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and affect both sexes equally. However, they constitute only about 2% of all neoplastic lesions involving the gastrointestinal tract. The age at presentation is variable but most patients are >50 years old (median

age around 60 years).14 GIST occurs rarely in children, most commonly in the second decade of life, but because of its unique clinicopathological characteristics, pediatric GIST is widely considered to be a distinct entity.15,16 Recent population-based studies suggest an incidence of 11 to 14.5 cases per million and the estimated incidence of GIST in the United States is around 4,500 to 6,000 new cases per year.17, 18 and 19 The majority of GISTs are sporadic, but some are familial with inherited germline mutations and others occur in syndromic settings. Well-recognized examples of syndromic GISTs include those that occur in patients with neurofibromatosis type I, Carney’s triad (GIST, paraganglioma, pulmonary chondroma), and the Carney-Stratakis syndrome (gastric GIST with paraganglioma). The syndromic GISTs are discussed in detail later in this chapter.

age around 60 years).14 GIST occurs rarely in children, most commonly in the second decade of life, but because of its unique clinicopathological characteristics, pediatric GIST is widely considered to be a distinct entity.15,16 Recent population-based studies suggest an incidence of 11 to 14.5 cases per million and the estimated incidence of GIST in the United States is around 4,500 to 6,000 new cases per year.17, 18 and 19 The majority of GISTs are sporadic, but some are familial with inherited germline mutations and others occur in syndromic settings. Well-recognized examples of syndromic GISTs include those that occur in patients with neurofibromatosis type I, Carney’s triad (GIST, paraganglioma, pulmonary chondroma), and the Carney-Stratakis syndrome (gastric GIST with paraganglioma). The syndromic GISTs are discussed in detail later in this chapter.

The stomach is the most common site of involvement (50%-60%) by GISTs, followed by the small intestine (25%) and the colorectum (˜10%). In the small intestine, two thirds of the tumors arise in the jejunum and about one third in the ileum. The duodenum and esophagus are primary sites of involvement of about 5% of cases each and appendiceal involvement is extremely rare (<1%). GISTs may also arise outside the gastrointestinal wall in the mesentery, omentum, or the retroperitoneum and are then referred to as extragastrointestinal stromal tumors.20, 21, 22 and 23

The majority of GISTs (70%) are clinically symptomatic and the spectrum of presenting symptoms is wide and related to tumor size. Most patients present with bleeding, early satiety, or bloating17 while chronic blood loss leading to fatigue or anemia may be the first manifestation in some patients. Approximately 20% of GISTs are asymptomatic and detected during clinical workup for unrelated reasons. Another 10% are found at autopsy or incidentally in gastric or esophageal resections performed for another primary tumor, which suggests that not all GISTs progress to clinically symptomatic tumors despite the presence of KIT gene mutations.24, 25 and 26

The preoperative tissue diagnosis of GISTs is often challenging, owing to their submucosal location and relative inaccessibility to standard endoscopic biopsy techniques. In recent years, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) coupled with fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology has significantly improved the ability to image gastric intramural masses and to obtain representative tissue samples. Distinctive features of GIST on EUS have been described, and this coupled with FNA not only provides a means for preoperative diagnosis but also allows for ancillary immunohistochemical or molecular testing on cell block material.27, 28 and 29

MORPHOLOGY

Macroscopic Features

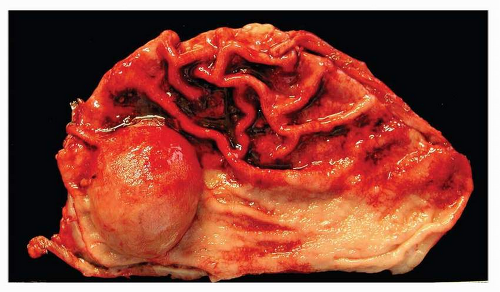

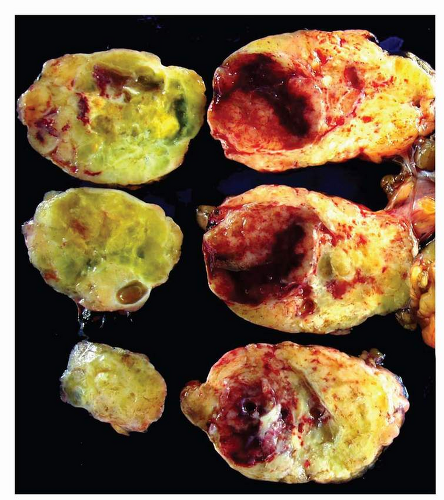

GISTs are well-circumscribed tumors, most often centered in the wall of the stomach or small intestine. The size range is wide and tumors may range from 1 cm to over 30 cm with a median size of about 5 cm. Extension into mucosa with surface ulceration or into the serosa with perforation of the serosal surface may be present in large tumors. Most tumors are gray-white and fleshy in appearance. Hemorrhage, necrosis, and cystic degeneration may be present. The latter two features are often quite prominent in large tumors or in resections performed after neoadjuvant treatment (Figs. 9-1, 9-2 and 9-3).

Microscopic Features

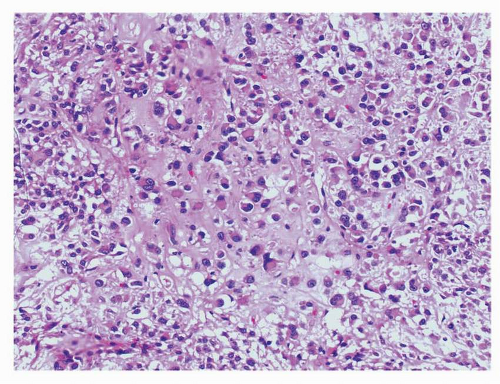

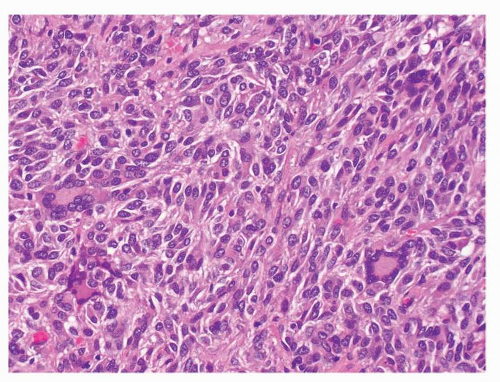

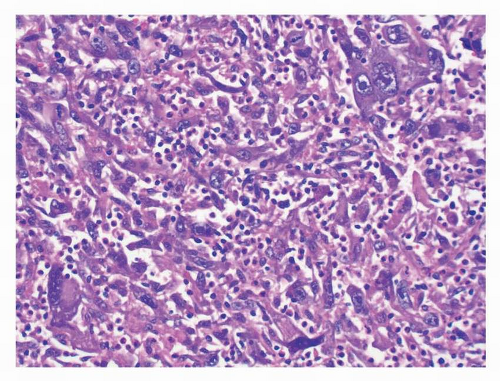

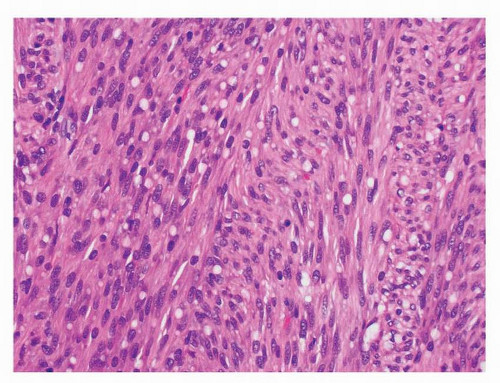

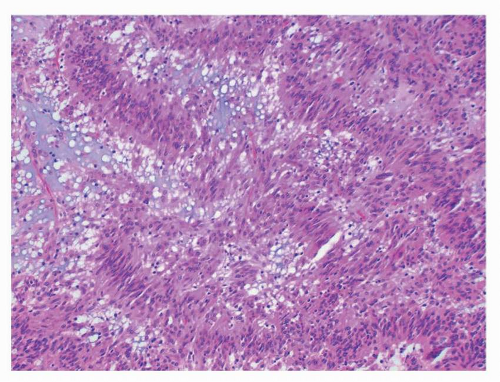

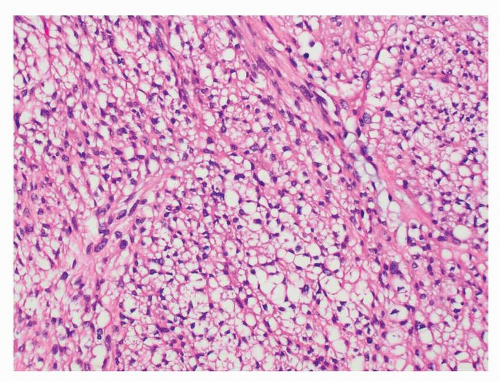

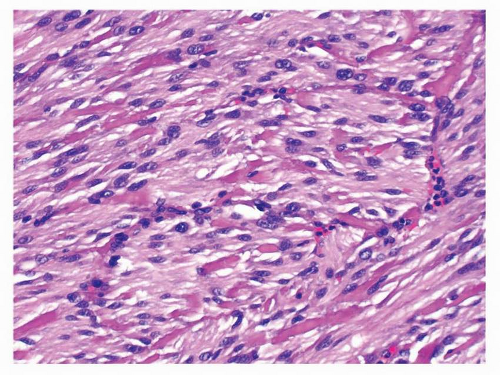

GISTs are divided microscopically into spindle, epithelioid, and mixed types. The spindle cell tumors are the most common (70%) type and show variable cellularity. The cells are arranged in a fascicular or storiform pattern and show pale, eosinophilic, fibrillary cytoplasm with ill-defined cell borders, which imparts a syncytial appearance to the tumor. The overwhelming majority of GISTs are monomorphic. They display oval, uniform nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. Paranuclear vacuoles, once thought to be a specific feature of true smooth muscle tumors, are particularly prominent in gastric GISTs. Striking nuclear palisading, reminiscent of neural tumors is present in about 50% of gastric and 70% of small intestinal GISTs. Approximately 20% of GISTs are composed exclusively of epithelioid tumor cells and the remaining 10% of tumors show a

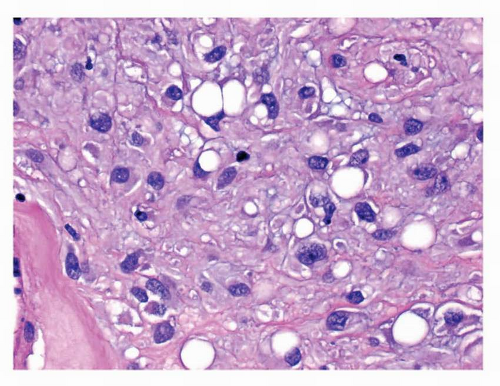

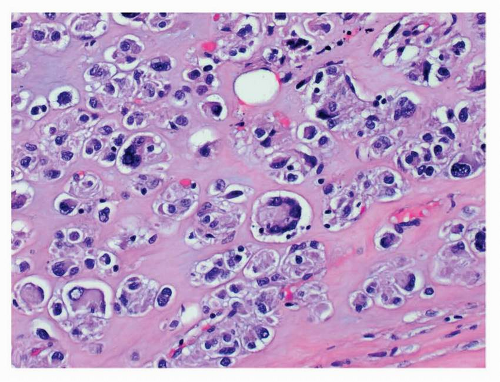

mixed spindle and epithelioid phenotype. Epithelioid GISTs occur more often in the stomach than in the small intestine. These tumors show round to polygonal cells arranged in a nested or sheetlike architecture. The tumor cells show a central or peripheral nucleus with abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm and sharply defined cell borders. Epithelioid tumors with prominent paranuclear vacuoles may mimic signet ring cell carcinoma. Mitotic activity is variable and high mitotic counts may be seen in any subgroup.

mixed spindle and epithelioid phenotype. Epithelioid GISTs occur more often in the stomach than in the small intestine. These tumors show round to polygonal cells arranged in a nested or sheetlike architecture. The tumor cells show a central or peripheral nucleus with abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm and sharply defined cell borders. Epithelioid tumors with prominent paranuclear vacuoles may mimic signet ring cell carcinoma. Mitotic activity is variable and high mitotic counts may be seen in any subgroup.

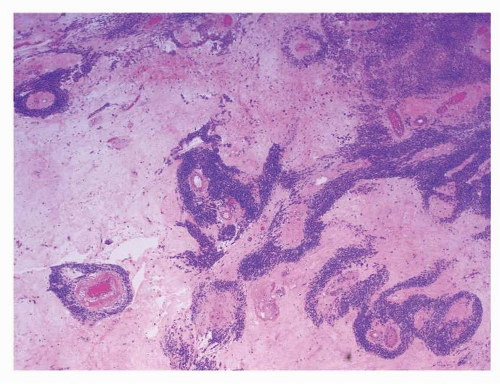

FIGURE 9-1 GISTs appear as wellcircumscribed submucosal mass lesions. The overlying mucosa is stretched over the lesion and may ulcerate in some cases. |

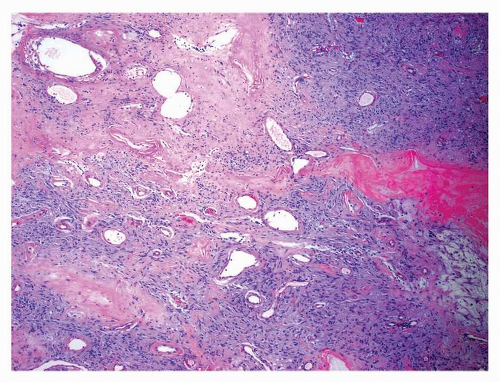

Various degenerative changes can be seen. The stroma may be sclerotic and hyalinized or myxoid in appearance. Calcification may be present in some tumors and is usually a degenerative change seen in the center of large tumors. Small intestinal tumors often show peculiar bright eosinophilic hyaline or fibrillar structures composed of tangles of collagen fibers that stain positively with a periodic acid-Schiff stain. These are known as “skeinoid” fibers and are present

in up to 40% of small intestinal GISTs and have been reported to be associated with a better prognosis in some studies.22

in up to 40% of small intestinal GISTs and have been reported to be associated with a better prognosis in some studies.22

FIGURE 9-2 The cut surface, particulary in small tumors, is homogenenous, fleshy white in consistency. |

FIGURE 9-3 Large tumors show a more variegated appearance with cystic change, hemorrhage, and necrosis. |

As mentioned above, the majority of GISTs are monomorphic and presence of significant nuclear atypia should prompt consideration of an alternate diagnosis. However, about 2% of true GISTs may show marked nuclear atypia to a degree usually seen in pleomorphic sarcomas. Molecular analysis of KIT and PDGFRA gene mutations is extremely useful in these cases.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with TKIs may lead to a marked reduction in cellularity accompanied by a myxohyaline stroma. In most instances, the tumor morphology following TKI therapy is comparable to the primary untreated tumor. However, transformation of spindle cell tumors to an epithelioid morphology and pseudopapillary growth patterns due to residual cuffs of viable tumor clustering around blood vessels have also been described. In rare instances, GISTs may show dedifferentiation, either de novo or following TKI therapy, into a high-grade sarcoma. Rhabdomyosarcomatous dedifferentiation has been described in which the transformed rhabdomyosarcomatous and the typical GIST components both show similar mutations in either the KIT or PDGFRA genes (Figs. 9-4, 9-5, 9-6, 9-7, 9-8, 9-9, 9-10, 9-11, 9-12, 9-13, 9-14, 9-15, 9-16 and 9-17).30, 31 and 32

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL FEATURES

Immunoreactivity for KIT (CD117) is a sensitive and specific marker for GIST and is extremely useful in the differential diagnosis of mesenchymal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. KIT is expressed in up to 95% of GISTs. CD34 is expressed in 60% to 70% of GISTs but is less sensitive

and specific than KIT.14,33 Immunoreactivity for KIT is variable in intensity and pattern. Most cases show strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining. Membranous or perinuclear dotlike (Golgi zone) staining may be present in some tumors, particularly in epithelioid GISTs. Focal weak staining may be present in some tumors that may be completely negative. Cases negative for KIT immunostain are more likely to be KIT wild type or PDGFRA mutant GISTs. Both KIT and CD34 may be negative in about 5% of GISTs34 and these tumors are more likely to be of epithelioid morphology. The stomach is a preferred location for these KIT-negative, epithelioid or mixed spindle and epithelioid GISTs. Treatment with TKI may also lead to loss of expression of both KIT and CD34, coupled with a gain in desmin reactivity.31,35

and specific than KIT.14,33 Immunoreactivity for KIT is variable in intensity and pattern. Most cases show strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining. Membranous or perinuclear dotlike (Golgi zone) staining may be present in some tumors, particularly in epithelioid GISTs. Focal weak staining may be present in some tumors that may be completely negative. Cases negative for KIT immunostain are more likely to be KIT wild type or PDGFRA mutant GISTs. Both KIT and CD34 may be negative in about 5% of GISTs34 and these tumors are more likely to be of epithelioid morphology. The stomach is a preferred location for these KIT-negative, epithelioid or mixed spindle and epithelioid GISTs. Treatment with TKI may also lead to loss of expression of both KIT and CD34, coupled with a gain in desmin reactivity.31,35

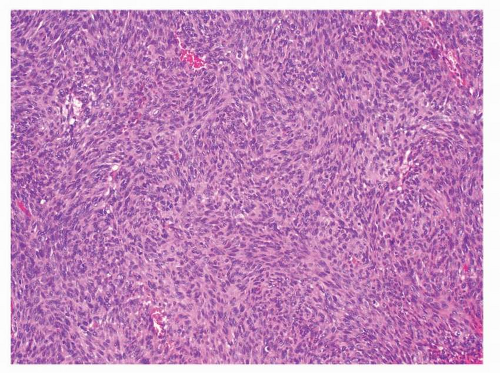

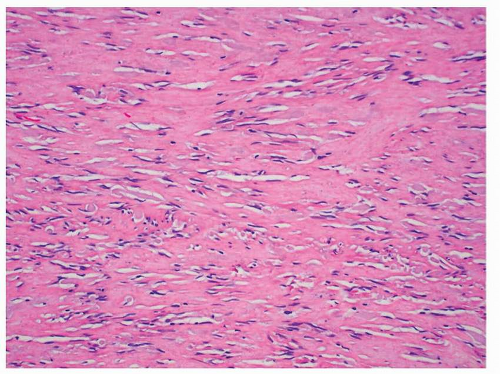

FIGURE 9-4 Spindle cell GISTs show a fascicular architecture. The tumor cells are monomorphic and show bland, elongated nuclei with prominent paranuclear vacuoles. |

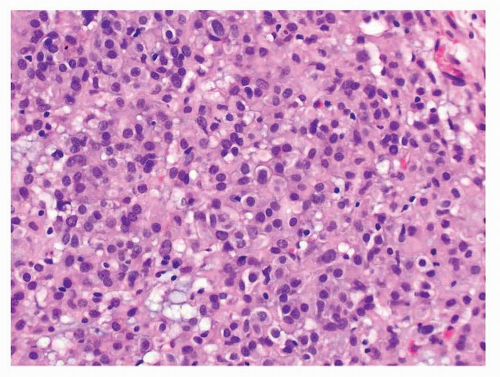

FIGURE 9-5 Epithelioid GISTs are also monomorphic and composed of round cells with central nuclei, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and sharp cell borders. |

FIGURE 9-6 The degree of cellularity in GISTs is variable. Hypercellular tumors may resemble a monomorphic spindle cell sarcoma, such as synovial sarcoma, MPNST, or fibrosarcoma. |

FIGURE 9-7 Hypocellular tumors show prominent collagenized stroma and resemble hypocellular areas of IMT. Unlike IMTs, plasma cell infiltration is not a conspicuous feature of GISTs. |

FIGURE 9-8 Central portions of large tumors may undergo infarction and necrosis. Ectatic vessels and hyalinized stroma impart a solitary fibrous tumorlike appearance to these areas. |

FIGURE 9-9 Nuclear palisading, reminiscent of neural tumors, is a common feature in GISTs and may be quite prominent, as in this example. |

FIGURE 9-10 Diffuse presence of paranuclear vacuoles in spindle cell GISTs can be mistaken for a clear cell epithelial or mesenchymal neoplasm, particularly in small biopsy specimens. |

FIGURE 9-12 Bright, eosinophilic, hyaline or fibrillary tangles of collagen fibers, known as skeinoid fibers, are more commonly seen in small intestinal GISTs. |

Smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, and H-caldesmon show variable reactivity in GISTs. SMA positivity ranges from 10% to 45%33 of cases, and is seen particularly in small intestinal GISTs. The largest series of gastric GISTs yielded SMA-positivity in only 19% of cases, and when positive, the staining was patchy.14,33 Desmin reactivity is much less prevalent but in the stomach has been reported in up to 30% of cases.14,36 H-caldesmon is reported to be positive in close to 80% of GISTs.35 Thus, of the three markers of myoid differentiation, desmin is the most discriminatory in differential diagnostic workup, since diffuse strong reactivity is seldom seen in GISTs and favors a primary smooth muscle tumor instead.

S-100 protein is positive in 1% to 5% of GISTs and is usually focal.14,33 Cytokeratin positivity is rare and occurs in <1% of tumors and high molecular weight keratins are generally absent.37, 38 and 39

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree