- Future diabetes care will continue to be delivered mainly in the primary care setting.

- Efforts must continue to bridge the gap between evidence-based recommendations and the current outcomes of patients with diabetes.

- The Chronic Care Model (CCM) provides the best evidence-based framework for organizing and improving chronic care delivery to ensure productive interactions between an informed activated patient and a proactive prepared practice team.

- The CCM defines six domains that require attention to optimize outcomes: delivery system design, self-management support, clinical

- information systems, decision support, community and health system-related issues.

- The most robust results are obtained when multiple elements of the CCM are incorporated together.

- Team-based care is a particularly effective strategy to improve diabetes outcomes.

- Future models for diabetes care need to continue to involve patients in designing the experience of the visit and various aspects of care improvement.

Introduction

The future of diabetes care will be shaped by the projections of increased incidence, producing more devastating complications and higher costs of care. Projections suggest that the worldwide prevalence of 6.6% in 2010 will increase to 7.8% in 2030. This translates into an increase in the number of individuals with diabetes from 285 million in 2010 to 435 million in 2030 [1]. Increased efforts to prevent the development of diabetes will be necessitated by current predictions that one out of three babies born in the USA will develop diabetes in their lifetime [2]. There is expected to be a dramatic increase in incidence of diabetes in low and middle income countries. Current health care costs associated with diabetes and its complications total more than $174 billion in the USA, and worldwide estimates are considerably higher. Despite the necessary efforts towards diabetes prevention, it is clear that with spiraling health care costs the millions of patients with diabetes will require better care models.

Many drivers for new care models are already in place, foremost of which appears to be financial. This is true whether the payer is a government authority, private insurer or purchaser of health care. Nearly a decade after the Institute of Medicine’s report describing Crossing the Quality Chasm [3], momentum continues to build for an implementation of better models of chronic illness care and diabetes is at the forefront of these efforts. In many ways, diabetes is the hallmark disease for studying quality improvement because of the prevalence, cost and strong evidence-base for specific quality goals. The challenge remains that despite strong agreement about minimum goals for HbA1c < 7% (53 mmol/mol), low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol <100mg/dL (26mmol/L) and blood pressure (BP) < 130/80 mmHg, fewer than 7% of Americans with diabetes are currently achieving these goals [4]. Key barriers to achieving these evidence-based patient goals are insufficient patient self-management support to facilitate adherence and clinical inertia. It has become increasingly clear that the systems of care are more responsible for these poorer outcomes than are either providers or patients.

Diabetes is one of the most psychologically and behaviorally challenging chronic illnesses to manage because as much as 95% of the management relies on the patients’ self-care efforts [5]. Despite this, the current health care system often does not have in place appropriate resources to foster patient self-management. Limitations in the availability of self-management education and the lack of ongoing self-management support impair patient adherence to self-care. Clinical inertia is defined as the clinician’s “recognition of the problem but failure to act” [6]. This refers to the situation where physicians fail to intensify therapy when faced with patients who are not meeting target goals for clinical variables. This inertia certainly has many components including decreased provider visit time, lack of timely appropriate data, inadequate provider attention to patient adherence and financial barriers. More information is ultimately needed on the basic epidemiology of clinical inertia including a careful analysis of associated patient, physician and clinic characteristics.

Compounding these challenges of self-management and clinical inertia is the plethora of new diabetes management data that is becoming available to the provider. The expanding use of continuous glucose monitoring, personal health records and shared web-based patient portals presents the risk of overwhelming diabetes care providers. Better management systems with appropriate filters and alerts are needed to analyze all these data and to present them in a usable format for providers.

Primary care is an important foundation of care in any health system. Starfield et al. [7,8] have shown that residents of countries with strong primary care foundations have improved health outcomes and lower mortality, with lower costs and with fewer health disparities. Despite the highest cost expenditure ($7000 per capita versus less than $3500 for Australia, Canada France, Germany, The Netherlands, New Zealand, and the UK), the USA has a weak primary care base and approximately 50 million uninsured citizens. It comes as no surprise that in a comparison of these eight developed Western nations, the USA had the most negative ratings for access, coordination and safety experiences [9]. What characterized all countries was the need for improved care systems.

For patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and those at risk for developing the disease, primary care physicians are a critical foundation of the health care delivery system. In the USA, patients with T2DM consulting a primary care physician outnumber those consulting an endocrinologist by almost 10 to 1 [10]. In general, patients at risk for T2DM are seen by primary care physicians and not by endocrinologists. Therefore, any reorganization of care will need to focus on the primary care settings.

Overall, the solutions to these issues will require reorganizing and reinventing diabetes care from a systems approach. In the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study, attitudes towards diabetes care were assessed across 13 countries from Asia, Australia, Europe and North America [11,12]. Although variation existed among countries in terms of both provider and patient perspectives of diabetes care, all respondents (primary care physicians, nurses and specialists) noted lack of care coordination and implementation of chronic disease strategies as an area in need of improvement worldwide. The payment system was also identified as a barrier in most of the countries surveyed, with the USA, Germany and Japan leading the way. Patients reported high ease of access to providers, but patients’ ratings of team collaboration among their providers were relatively low. By the same token, primary care physicians noted a lack of multidisciplinary care and a need for more coordination of care. This chapter focuses on the most promising models for diabetes care, provides current examples and attempts to project into the future how these systems will evolve.

The Chronic Care Model

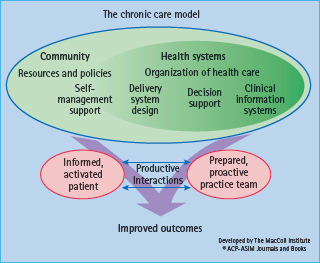

Although several approaches have been utilized to translate evidence-based recommendations into clinical practice, the Chronic Care Model (CCM) has been the most effective model that has been implemented in a variety of clinical settings in the USA and internationally, often with diabetes as the focus disease [13]. The CCM proposes that the productive interactions of a prepared proactive practice team and an informed empowered patient and family will lead to improved outcomes (Figure 62.1). This provides a conceptual framework and roadmap for redesigning care from the typical acute reactive system to one transformed to population-based proactively planned care of individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes. Mounting evidence from comparison of high and lower performing practices, evaluation of large-scale quality improvement efforts and randomized intervention trials have demonstrated that the implementation of the CCM is feasible by busy practices with resultant improved disease outcomes [14].

Figure 62.1 The Chronic Care Model. Reproduced from www.improvingchroniccare.org with permission from Group Health Research Institute.

The CCM has been employed for diabetes in a number of health care settings and has demonstrated improvement in cardiovascular risk factors [15,16] and reductions in HbAlc [16], along with improvements in complication screening. Although simpler interventions would be attractive, the evidence suggests that high performing practices do best when they incorporate multiple elements of the CCM [17–21].

The CCM focuses on six elements:

Delivery system design

Although the best results are obtained when multiple facets of the CCM are implemented together, probably the single most effective quality improvement intervention in diabetes care involves delivery system design to incorporate a team-based approach [23]. Other key elements of delivery system design are case management and shared care.

Realistically, primary care providers have reached their limit in terms of additional tasks that they can undertake, and therefore it is inevitable that the care team needs to be expanded. In many ways, team management has been considered a central feature of superior diabetes care. Diabetes educators and dietitians have long been part of standard diabetes care and the expansion of the roles of these and other individuals within the health care system will likely continue.

Team-based care allows task distribution which includes indentifying team members to:

Standing orders can be used to empower office staff to order overdue laboratory screening and eye exam referral, and can even extend to algorithms for medication intensification. Appropriate communication between team members is the key, and the incorporation of clinic “huddles” at the beginning of the day can ensure that appropriately planned care is delivered to all individuals with diabetes.

Diabetes has been a fertile testing ground for case management approaches in which usually either a nurse or pharmacist meets regularly with high-risk patients to provide intensified care [23,24]. Care populations are segmented based on needs to ensure that appropriate care intensity is provided. Key elements of care management include:

Diabetes nurses are eager to increase their involvement and take on more responsibility for diabetes care, as recently surveyed internationally through the DAWN study [11]. Pharmacists have also been utilized to work in conjunction with primary care physicians in a case management role. Recent reimbursement changes within the US Medicare system have facilitated billing for these services based on non-randomized trials in which this care has been found to be cost-effective [25].

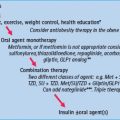

Care management approaches have been effective at improving glucose control, BP and lipid control in many different settings in the USA and elsewhere [23,24]. One controversy has been the extent to which case management permits medication titration. Two models have been used: one in which the case manager advises the primary care physician who then makes the medication change versus the second in which a standing order algorithm enables a case manager to intensify treatment without routinely checking with the primary care provider. Although studies suggest that standing order algorithms are more effective in lowering HbA1c levels [23,24], some physicians have concerns about nurses or pharmacists making these changes without routine provider input. As more studies and appropriate training programs are developed to allow other health professionals to assist in medication titration, this approach will continue to show promise in improving clinical outcomes while not overburdening the already overtaxed primary care system.

Shared care is defined as “the joint participation of primary care physicians and specialty care physicians in the planned delivery of care, informed by an enhanced information exchange over and above routine discharge and referral notices as the co-management of patients by primary care and subspecialty specialists” [26]. Currently, when most patients are referred to endocrinolo-gists, care is subsumed by the specialists and true co-management is rare. In a recent Cochrane review which examined shared care across multiple chronic illnesses, limited data were available on effective models [27].

Self-management support

A distinction needs to be made between self-management support and self-management education. Self-management education is quite familiar in the diabetes community and encompasses the traditional role of the diabetes educator providing knowledge and skills to patients with diabetes. Self-management support, however, needs not be performed by a diabetes educator and, in fact, peer coaches have been utilized to foster self-management support. Self-management support involves the ongoing collaborative approach between coach and patients to define problems, set priorities, establish goals and create treatment plans. Resources offered to problem solve can include community-based organizations, peer support programs and other groups. Individualized approaches that address the major concerns defined by the patient typically involve a strong element of coaching with the goal of educating and empowering the patient. The challenge for the future is to make self-management support more widely available. Innovative approaches that leverage information technology to provide patient coaching are possible solutions [28].

Self-management has long been recognized as a key determinant of disease outcome. Traditional diabetes education programs have focused on knowledge and specific skills training. It has become increasingly clear, however, that knowledge is necessary but not sufficient to influence behavior. This has led to increased attention to determinants of patient behavior change. In this regard, importance and confidence for a behavior change are key determinants [29].

Importance and confidence

The overall importance of a behavior change is judged by the patients based on their values. Knowledge and education can clearly influence importance by providing the rationale for health improvement. Confidence, also referred to as self-efficacy, is the inherent confidence that a patient can be successful in making the behavior change. This can be augmented through problem-solving and discussion of alternative strategies. Adherence to diet, exercise, monitoring and medication are required for optimal diabetes outcomes. Although many social and societal factors influence patient adherence, clinician counseling style has a profound impact on potential behavior change. Providers can either increase resistance to change or help to facilitate readiness to change on the part of the patient. Patient empowerment and increased self-efficacy are key factors in enabling patients to feel confident in making necessary changes. Recent years have brought to the forefront behavior change approaches from the psychologic literature to be applied to diabetes. One of the most promising approaches is motivational interviewing [29,30].

Motivational interviewing is a directive patient-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping patients to explore and resolve ambivalence. It is a collaborative patient-provider model that stresses that motivation must come from the patient, not the provider, and honours and respects the patient’s autonomy. Initially utilized in the addiction field, it is now being applied to a number of chronic diseases including diabetes [31]. It is a teachable evidence-based approach that holds significant promise to improve patient adherence. Part of the attractiveness of motivational interviewing has been the well-defined set of skills that can be taught to different individuals. Certified trainers are available worldwide [32]. Brief motivational interviewing has adapted many of the skills of traditional motivational interviewing, as used by psychologists, for use in the busy time-pressured health care environment. Meta-analyses have shown this to be a powerful approach which can be learned by people with varying backgrounds and applied to multiple chronic illnesses [31]. Early studies in diabetes are promising [33,34] and larger scale trials are currently underway [35].

Several other behavior change models/theories, which can either explain or help practitioners conceptualize behavior change, have been identified. They include the health belief model, theory of reasoned action or theory of planned behavior, stages of change or transtheoretical model, social cognitive or social learning theory, community organization/building, and social marketing [36].

Clinical information systems

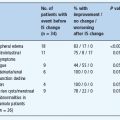

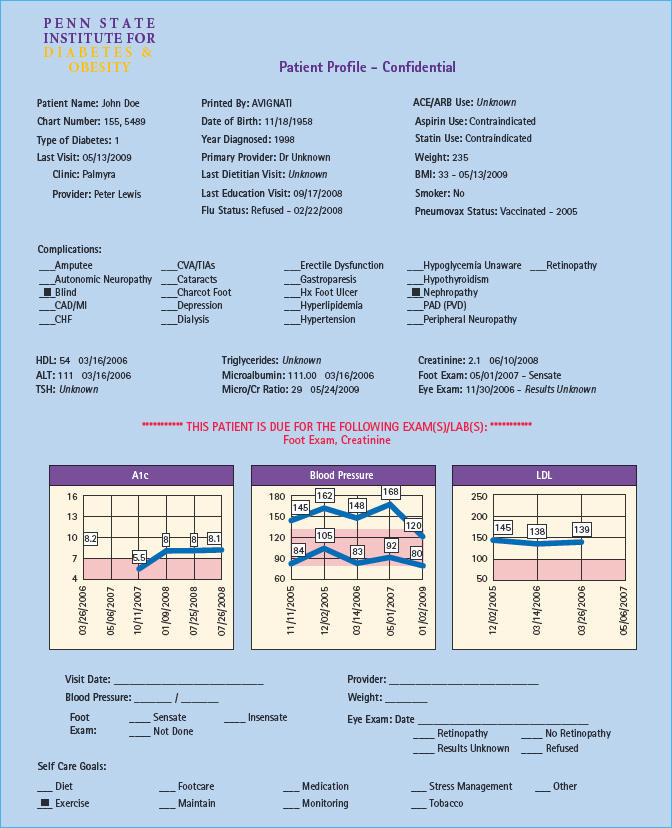

Clinical information systems help to organize patient and population data to facilitate effective and efficient care delivery. Diabetes registries are being adopted in a variety of health care settings involving municipalities, academic health centers, third-party payers, the US Veterans Affairs Health System and international registries in Europe, Canada and elsewhere [37]. A registry is a searchable list of all patients with a particular chronic disease. The well-designed registry lists all members of the patients’ health team and provides key information for patients and providers. The critical impact of the registry is that it can allow timely identification of high-risk subpopulations, permitting the health care team to intensify treatment. A registry can also provide snapshots of care that can collate the many data elements needed for optimal care (e.g. last eye exam, foot exam, nephropathy screen, HbA1 c, cholesterol, BP) and can include prompts for care (decision support) as seen in Figure 62.2.

Figure 62.2 An example of an electronic registry flowsheet. A1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree