Flat Urothelial Lesions

There are four main reasons a surgical pathologist is asked to evaluate flat (cystoscopically apparent or unapparent) lesions. The first two indications involve multiple random biopsies by cold cup biopsy technique (a) in patients previously diagnosed with noninvasive or lamina propria-invasive papillary tumors who are on surveillance for bladder cancer and (b) in patients who are diagnosed with papillary bladder carcinoma for the first time. The aim of the biopsies is to detect flat intraurothelial disease, which suggests urothelial instability, multifocality, and proclivity for disease progression. The third indication is in patients with hematuria, dysuria, and increased frequency of micturition, who have positive urine cytology, positive FISH UroVysion, or are at high risk of development of bladder cancer. The aim is to detect urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS), which may or may not be cystoscopically apparent. The fourth indication is in patients without a high risk of bladder cancer but who present with urinary symptoms similar to those listed but who do not respond to routine medical treatments. In this setting, biopsies are performed to evaluate other causes for the symptoms. Significant flat urothelial disease may be inapparent by cystoscopy, and this has promulgated the concept of performing random bladder biopsies in patients with cancer, resulting in most of the flat lesions seen clinically (1).

APPROACH TO THE EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF FLAT LESIONS

The widely used and recommended classification is the World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) classification of flat intraurothelial lesions, which is outlined in Table 2.1 (2, 3, 4). The system first proposed as the WHO/ISUP (1998) system has subsequently been largely adopted in its entirety during revisions of the WHO Blue Books (2004 and 2016). The approach to the diagnosis of lesions within this classification requires attention to several organizational and cytologic features within the urothelium, the constellation of the presence or absence of which helps make the correct diagnosis (5) (Table 2.2).

On low-power examination, one should pay attention to several features including the thickness of the urothelium, overall polarity, presence

or absence of cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and neovascularity at the base of the urothelium. Observation regarding the thickness of the urothelium may provide useful clues. It is normally three to seven layers in thickness, depending on the state of distention. Denudation may be seen in reactive conditions (trauma or infection) or CIS. Hyperplastic urothelium may be encountered in the entire spectrum of flat intraepithelial lesions (reactive atypia, dysplasia, and CIS), and its presence merits evaluation of cytologic features, on the basis of which the diagnosis is ultimately made. Other features assessed at low power include polarity, nuclear crowding, and cytoplasmic clearing. In the normal urothelium, the cells are arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane with orderly organization of the basal cells, intermediate cells, and superficial umbrella cells. Loss of normal polarity and presence of nuclear crowding are often indicative of intraurothelial neoplasia. Loss of cytoplasmic clearing (increased eosinophilia) is also a sign of dysplasia or CIS. Nucleomegaly is objectively determined by comparison if clearly normal urothelium is present in the biopsy.

or absence of cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and neovascularity at the base of the urothelium. Observation regarding the thickness of the urothelium may provide useful clues. It is normally three to seven layers in thickness, depending on the state of distention. Denudation may be seen in reactive conditions (trauma or infection) or CIS. Hyperplastic urothelium may be encountered in the entire spectrum of flat intraepithelial lesions (reactive atypia, dysplasia, and CIS), and its presence merits evaluation of cytologic features, on the basis of which the diagnosis is ultimately made. Other features assessed at low power include polarity, nuclear crowding, and cytoplasmic clearing. In the normal urothelium, the cells are arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane with orderly organization of the basal cells, intermediate cells, and superficial umbrella cells. Loss of normal polarity and presence of nuclear crowding are often indicative of intraurothelial neoplasia. Loss of cytoplasmic clearing (increased eosinophilia) is also a sign of dysplasia or CIS. Nucleomegaly is objectively determined by comparison if clearly normal urothelium is present in the biopsy.

TABLE 2.1 The WHO/ISUP Classification of Flat Intraurothelial Lesions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

TABLE 2.2 Histologic Parameters Useful in the Evaluation of Flat Lesions with Atypia | |

|---|---|

|

If normal urothelium is not present, stromal lymphocytes may also be used for size comparison. The larger nuclei in CIS are often five times the size of a normal lymphocyte, whereas the nuclear size of normal urothelium and dysplastic urothelium is only approximately twice the size of lymphocytes, aiding in their distinction from CIS (6). The presence of dysplasia is confirmed by unequivocal nuclear atypia (nuclear border and nuclear chromatin abnormalities) but does not meet the threshold for CIS. The presence of nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitoses (including atypical mitotic figures or surface mitoses), and prominent nucleoli (single or multiple) throughout much of the urothelium favor a diagnosis of urothelial CIS over that of urothelial dysplasia or reactive changes. Nucleolar pleomorphism (multiple nucleoli of varying sizes and shapes) may be seen in CIS and is a helpful feature when present. Neovascularization in a bladder biopsy without history of previous treatment suggests the presence of a host response to an intraurothelial neoplastic process and is more commonly seen in CIS.

HISTOLOGIC FEATURES OF FLAT INTRAUROTHELIAL LESION CATEGORIES

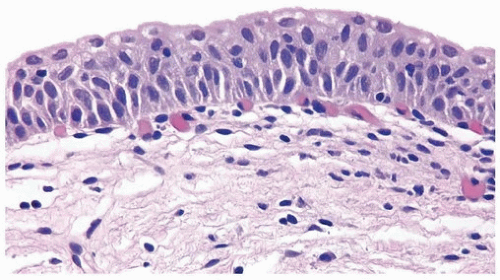

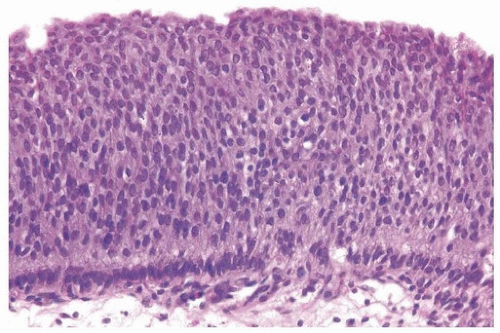

Normal

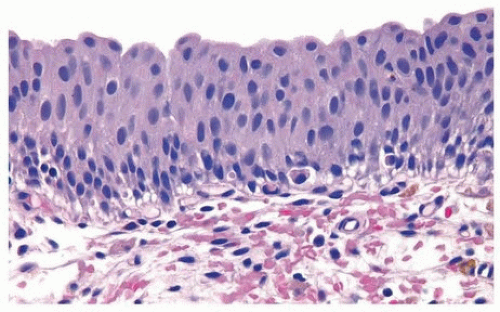

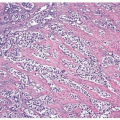

The normal urothelium, as mentioned previously, is composed of three cell types: basal, intermediate, and superficial cells arranged in three to seven cell layers, with the thickness varying depending on the state of distention (Fig. 2.1) (efigs 2.1-2.7). The nuclei of basal cells are small and hyperchromatic, and the cells usually form a single layer. The intermediate cells constitute the bulk of the urothelium, the cells are oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane, and the nuclei are usually oval to round in tissue sections. Nuclear grooves are frequently identified. The cytoplasm is clear to amphophilic. The superficial or umbrella cells are arranged parallel to the basement membrane and are large, with one cell typically spanning or covering several intermediate cells (like an umbrella). The nucleus is small, and cytoplasm is voluminous and clear or eosinophilic. Mild degrees

of architectural variation (apparent loss of polarity) but without cytologic atypia are considered acceptable to be designated as normal (Figs. 2.2, 2.3). This is often due to tangential or thick sectioning.

of architectural variation (apparent loss of polarity) but without cytologic atypia are considered acceptable to be designated as normal (Figs. 2.2, 2.3). This is often due to tangential or thick sectioning.

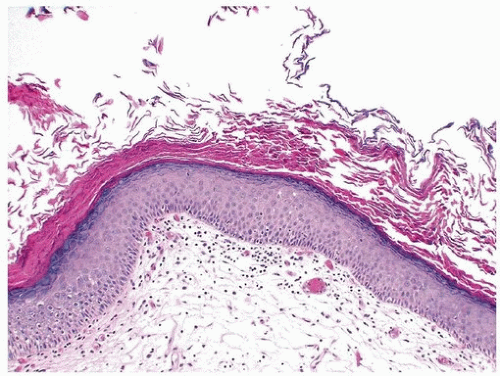

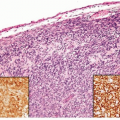

Squamous Metaplasia

Nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium metaplasia, particularly in the area of the trigone, is a common finding in premenopausal women and is responsive to estrogen production (efigs 2.8-2.12). This type of squamous mucosa is characterized by abundant intracytoplasmic glycogen and lack of keratinization, making it histologically similar to vaginal or cervical squamous epithelium (Fig. 2.4) (see Chapter 9 for additional images) (7). It is likely that trigonal squamous mucosa in women represents a normal histologic variant unassociated to local injury. Under other pathologic conditions, the metaplastic squamous epithelium, that is, nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa in males and/or in nontrigonal locations or mucosa with keratinization in either sexes, may exhibit parakeratosis and even a

granular layer (8) (Fig. 2.5) (efig 2.13). This metaplastic epithelium is not preneoplastic per se but under some circumstances may lead to squamous carcinoma (see Chapter 9), particularly where multifocal and extensive.

granular layer (8) (Fig. 2.5) (efig 2.13). This metaplastic epithelium is not preneoplastic per se but under some circumstances may lead to squamous carcinoma (see Chapter 9), particularly where multifocal and extensive.

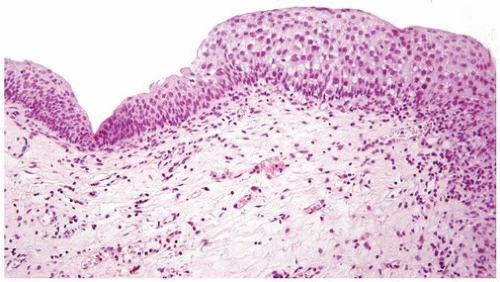

FIGURE 2.3 Tangentially sectioned cytologically appearing normal urothelium with umbrella cells showing slight atypia. |

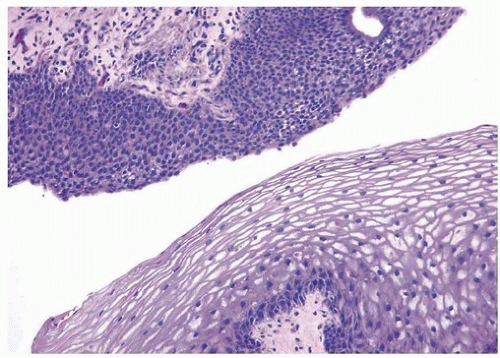

Flat Urothelial Hyperplasia

The urothelium is markedly thickened and, importantly, lacks cytologic atypia (Fig. 2.6) (efigs 2.14-2.16). Rather than requiring a specific number of cell layers, marked thickening and/or increased cell density within the urothelium (increased cells per unit area) is needed to diagnose flat hyperplasia. This lesion may be seen in the flat mucosa adjacent to low-grade

papillary urothelial lesions. When seen alone in a de novo setting, there are no data to suggest that it has a premalignant potential. When these lesions occur in the setting of papillary tumors, flat hyperplasia may contain genetic abnormalities (chromosome 9 abnormalities and FGFR3 mutations) indicating that this may be an early manifestation of low-grade urothelial neoplasia (9, 10).

papillary urothelial lesions. When seen alone in a de novo setting, there are no data to suggest that it has a premalignant potential. When these lesions occur in the setting of papillary tumors, flat hyperplasia may contain genetic abnormalities (chromosome 9 abnormalities and FGFR3 mutations) indicating that this may be an early manifestation of low-grade urothelial neoplasia (9, 10).

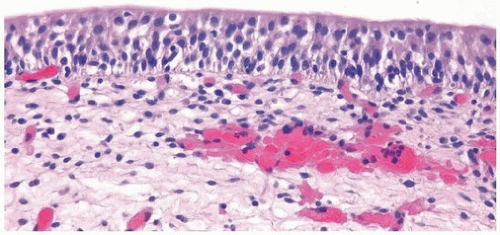

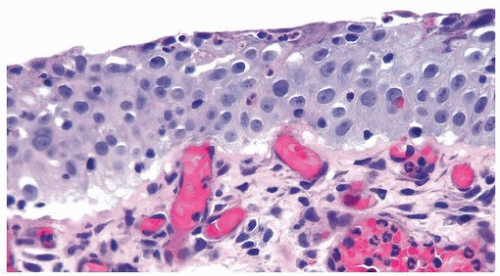

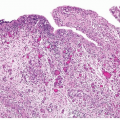

Reactive Urothelial Changes

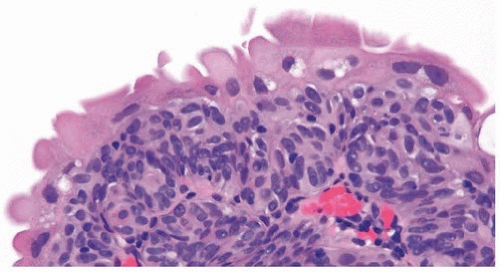

As “reactive urothelial atypia” may in some instances lead to confusion with dysplasia or cause concern for patients, some of the current authors have substituted the term “reactive urothelial changes.” Nucleomegaly is the most prominent finding in reactive urothelial changes, but the cells often have a single prominent nucleolus and evenly distributed vesicular chromatin (Fig. 2.7) (efigs 2.17-2.28). The nuclear borders are smooth. The nuclei are frequently round, and nuclear pleomorphism is lacking (11).

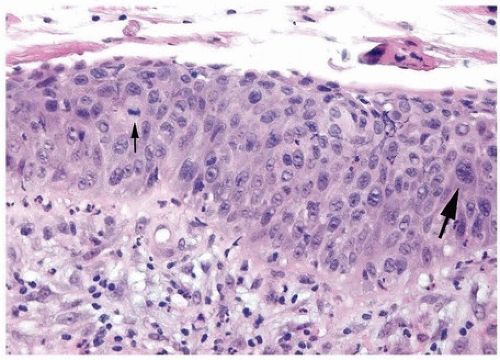

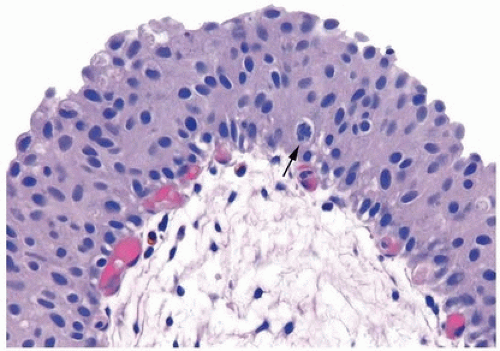

FIGURE 2.8 Reactive urothelium with scattered lymphocytes and neutrophils within the urothelium showing mitotic figure (arrow). |

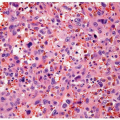

Architecturally, the cells maintain their polarity perpendicular to the basement membrane although a minimal loss of polarity may be evident. The mitotic rate may be increased with mitoses present predominantly in the basal and intermediate urothelium, but atypical forms are not seen. Intraurothelial acute or chronic inflammation is commonly identified (Figs. 2.8, 2.9, 2.10). It is important to recognize that even intraepithelial lymphocytes, by themselves, can result in reactive changes. The cytoplasm may become more basophilic or eosinophilic with loss of cytoplasmic clearing. Clinical history of stones, infection, or frequent instrumentation may be present (12). Reactive urothelium may be denuded with only a single residual layer of basal cells remaining; the residual cells are not hyperchromatic, not enlarged, and do not possess nuclear membrane irregularity.

The umbrella cells frequently undergo reactive change alone and exhibit multinucleation or nucleomegaly, often with cytoplasmic vacuolation. Although reactive conditions share the presence of enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses with CIS, in reactive conditions, nuclei are uniform in size and shape with vesicular nuclei as opposed to the often hyperchromatic nuclei of CIS. Furthermore, most cases of CIS are not associated with intraepithelial inflammation.

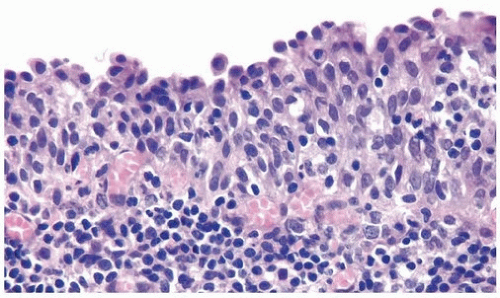

Urothelial Atypia of Unknown Significance

This term was originally proposed as a descriptive category in cases with inflammation in which the severity of atypia appears to be out of proportion to the extent of inflammation such that dysplasia or CIS could not be confidently excluded (Figs. 2.11, 2.12) (efigs 2.29). The message

conveyed to the urologist by use of this diagnostic terminology was that the patient should be followed up after inflammation subsides. This was not a disease or diagnostic entity but merely a descriptive term that may be designated in a biopsy in which the flat lesion with atypia cannot be diagnosed with certainty into reactive, dysplastic, or CIS categories. Since this term is often used loosely and potentially as a “wastebasket” term by pathologists for lesions with minimal atypia that may well fall into the spectrum of “normal,” we dissuade the use of this term and suggest that pathologists acknowledge the level of diagnostic difficulty in cases where it is not possible to reliably exclude reactive from neoplastic atypia, than use this term. Studies have shown that cases diagnosed as reactive atypia and atypia of unknown significance have similar clinical features and are not associated with progression to bladder cancer (13, 14), further supporting our position.

conveyed to the urologist by use of this diagnostic terminology was that the patient should be followed up after inflammation subsides. This was not a disease or diagnostic entity but merely a descriptive term that may be designated in a biopsy in which the flat lesion with atypia cannot be diagnosed with certainty into reactive, dysplastic, or CIS categories. Since this term is often used loosely and potentially as a “wastebasket” term by pathologists for lesions with minimal atypia that may well fall into the spectrum of “normal,” we dissuade the use of this term and suggest that pathologists acknowledge the level of diagnostic difficulty in cases where it is not possible to reliably exclude reactive from neoplastic atypia, than use this term. Studies have shown that cases diagnosed as reactive atypia and atypia of unknown significance have similar clinical features and are not associated with progression to bladder cancer (13, 14), further supporting our position.

FIGURE 2.11 Atypia of unknown significance with scattered hyperchromatic nuclei yet prominent inflammation. |

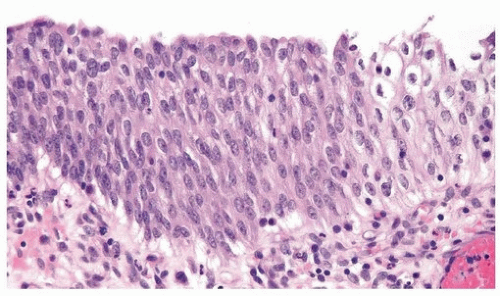

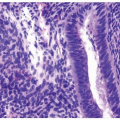

Urothelial Dysplasia

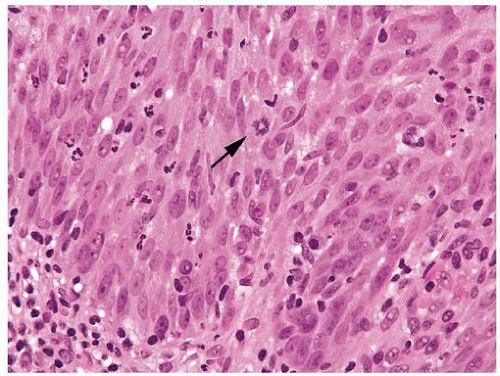

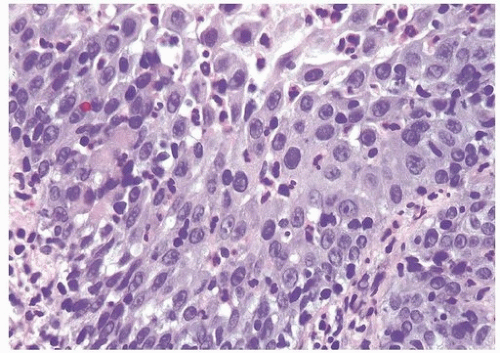

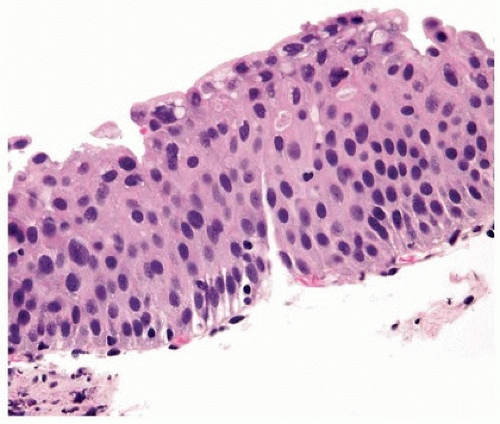

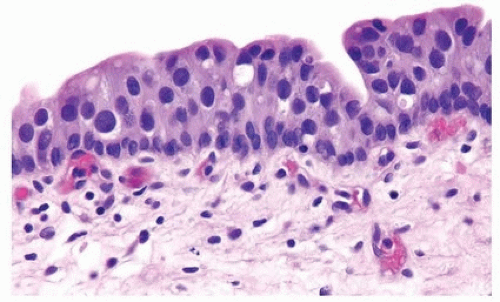

Distinct appreciable nuclear abnormalities in the urothelium that occur in the absence of inflammation or that appear disproportionate to the amount of inflammation (if present), but that are not severe (i.e., falling below the threshold of CIS), may be designated as urothelial dysplasia/low-grade intraurothelial neoplasia (Figs. 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 2.16) (efigs 2.20-2.39). It has been proposed that bladder intraepithelial lesions, like intraepithelial lesions of the cervix, be graded on the basis of level of involvement of atypical cells (i.e., mild dysplasia for lesions showing atypia confined to the lower one third, moderate dysplasia for atypia up to the middle third, and so on) (15). However, observations in animal models and in clinical specimens indicate the importance of cytologic features (degree of cytological atypia) rather than histologic pattern (extent of atypia from the basal layer) (16).

FIGURE 2.14 Urothelial dysplasia with loss of polarity, scattered small yet hyperchromatic nuclei, and a mitotic figure (arrow). |

FIGURE 2.15 Urothelial dysplasia with scattered hyperchromatic nuclei. Although there is considerable nuclear atypia, the collective features fall short of the diagnosis of CIS. |

FIGURE 2.16 Urothelial dysplasia with scattered, enlarged nuclei. Although there is considerable nuclear atypia, the collective features fall short of the diagnosis of CIS. |

In dysplasia, the thickness of the urothelium is usually normal (three to seven layers) but may be decreased or increased (Fig. 2.17). Flat lesions with a benign cytology and minimal disorder should be considered within the spectrum of “normal” (17). Dysplastic lesions show loss of polarity (normal cells are columnar to oval with nuclei perpendicular to the basement membrane) evidenced by crowding of nuclei. The cells are more rounded to polygonal cells with nuclei parallel to the long axis. Nuclear atypia is evident but is not severe enough to merit a diagnosis of CIS. Often, increased cytoplasmic eosinophilia, nucleomegaly, irregularity of nuclear contours with notching of cell borders, and altered chromatin distribution are seen. Nucleoli are usually not conspicuous or are only randomly

present in the mucosa but are not typically present throughout. Only a minimal degree of pleomorphism is allowable in dysplasia, and the mitotic activity is variable although usually not in the higher layers. The lamina propria is usually unaltered, but it may contain increased inflammation or neovascularity. Denudation with atypical cells clinging to the submucosa is not a common feature of dysplasia. Comparison with more normalappearing urothelium, if present in the same biopsy specimen or in another simultaneously obtained biopsy specimen from the same patient, may help in assessing features such as nucleomegaly, loss of clearing, and loss of polarity. In some patients on surveillance for low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, due to increased frequency of cystoscopy, early lesions may be found, which histologically show thickened urothelium with dysplasia. Early papillary formation or neovascularity at base, similar to papillary hyperplasia, may be present. Similar abnormalities in the urothelium may be seen in the mucosa immediately adjacent to a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma (shoulder effect). Another way to conceptualize the difference between dysplasia and CIS is that the cytological findings seen in dysplasia are analogous to those seen in noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, whereas CIS is analogous in its histology to noninvasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Immunostaining is not recommended in the distinction between dysplasia and CIS (for potentially useful immunoprofile, see section on CIS below) as the distinction is based purely on morphologic grounds with the former denoting distinct nuclear atypia falling short of the threshold to be designated as CIS.

present in the mucosa but are not typically present throughout. Only a minimal degree of pleomorphism is allowable in dysplasia, and the mitotic activity is variable although usually not in the higher layers. The lamina propria is usually unaltered, but it may contain increased inflammation or neovascularity. Denudation with atypical cells clinging to the submucosa is not a common feature of dysplasia. Comparison with more normalappearing urothelium, if present in the same biopsy specimen or in another simultaneously obtained biopsy specimen from the same patient, may help in assessing features such as nucleomegaly, loss of clearing, and loss of polarity. In some patients on surveillance for low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, due to increased frequency of cystoscopy, early lesions may be found, which histologically show thickened urothelium with dysplasia. Early papillary formation or neovascularity at base, similar to papillary hyperplasia, may be present. Similar abnormalities in the urothelium may be seen in the mucosa immediately adjacent to a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma (shoulder effect). Another way to conceptualize the difference between dysplasia and CIS is that the cytological findings seen in dysplasia are analogous to those seen in noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, whereas CIS is analogous in its histology to noninvasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Immunostaining is not recommended in the distinction between dysplasia and CIS (for potentially useful immunoprofile, see section on CIS below) as the distinction is based purely on morphologic grounds with the former denoting distinct nuclear atypia falling short of the threshold to be designated as CIS.

A diagnosis of primary dysplasia (i.e., no prior history or concomitant urothelial neoplasia) should be made with great caution (18, 19). Dysplasia is usually a histologic diagnosis seen most commonly in patients with bladder neoplasia, in whom the incidence is 22% to 86%. The incidence approaches 100% in patients with invasive carcinoma. Little is known about de novo dysplasia because there is a lack of screening in the general population. Furthermore, de novo dysplasia is usually cystoscopically and clinically silent, although it may appear as a slightly raised and mildly erythematous patch. The patients are predominantly middle-aged men presenting occasionally with irritative bladder symptoms with or without hematuria. The few studies published on de novo dysplasia indicate that 5% to 19% of patients progress to have urothelial neoplasia (20, 21, 22, 23). The finding of dysplasia in patients with bladder cancer suggests that it is a marker for progression (increased recurrences or future invasion) (13, 24, 25). However, the definition of dysplasia used in all these studies has been variable, so their true clinical meaning remains in doubt. In general, the diagnosis of dysplasia suffers from poor interobserver reproducibility, even among expert genitourinary pathologists.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree