William F. Wright, Philip A. Mackowiak

Fever of Unknown Origin

Most episodes of fever in humans are short-lived and do not require diagnostic investigation or specific therapy. Some are manifestations of more serious illnesses, most of which can be readily diagnosed and effectively treated. However, small but important subgroups of fevers are both persistent and difficult to diagnose. Such puzzling fevers have fascinated and frustrated clinicians since the earliest days of clinical thermometry,1 resulting in a welter of clinical publications. The two most important of these, from a historical perspective, are the classical treatises, Prolonged and Perplexing Fevers, published by Keefer and Leard in 1955,2 and Fever of Unknown Origin: Report on 100 Cases, by Petersdorf and Beeson in 1961.3

Terminology and Definitions

In the United States, the term fever of unknown origin (FUO) is generally used.4 In other countries an alternative term, pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO), is often used.5

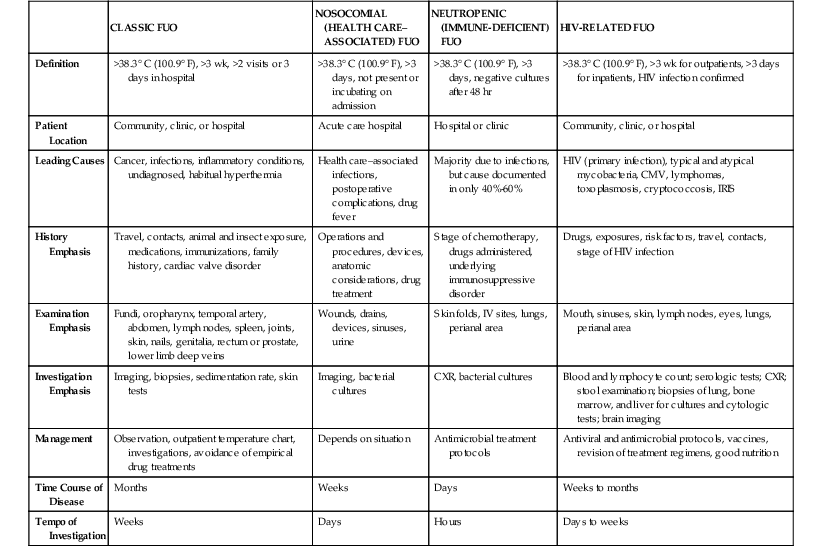

The first formal definition of FUO to gain broad acceptance was proposed by Petersdorf and Beeson nearly 5 decades ago: “fever higher than 38.3° C (100.9° F) on several occasions, persisting without diagnosis for at least 3 weeks in spite of at least 1 week’s investigation in hospital.”3 Later investigators have modified and extended this classic definition to reflect evolutionary changes in clinical practice.6,7 These changes include the conduct of most diagnostic tests in the outpatient setting rather than in the hospital, the increasing number of immunocompromised patients (especially those with neutropenia), the proliferation of increasingly complex surgical and intensive care treatment protocols, and the advent of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection leading to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In response to this evolving environment, Durack and Street,7 in 1991, proposed a revised definition in which cases of FUO are currently codified into four distinct subclasses of the disorder: classic FUO, nosocomial (health care–associated) FUO, neutropenic (immune-deficient) FUO, and HIV-related FUO (Table 56-1). Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound imaging, nucleic acid–based diagnostic testing, and rapid tests for pathogens have enlarged the diagnostic options for FUO. One could argue that the definitions of types of FUO have much overlap and are not as clinically useful as they were in the past. In a prospective study of 80 patients based on these two main definitions, Ergonul and colleagues8 found that although the 1991 definition included more cases within the infectious diseases group, the overall distribution of diseases among the two definitions was not significantly different.

Classic Fever of Unknown Origin

Classic FUO refers to the type of FUO defined by Petersdorf and Beeson in 1961.3 The only alteration to their definition required to conform to modern medical practice is to incorporate investigation in the outpatient setting, which today has become the preferred venue for evaluation and treatment. Most patients with classic FUO have subacute or chronic symptoms and therefore can be safely investigated as outpatients. In a series of 53 such patients, for example, the median duration of fever before diagnosis was 40 days.1

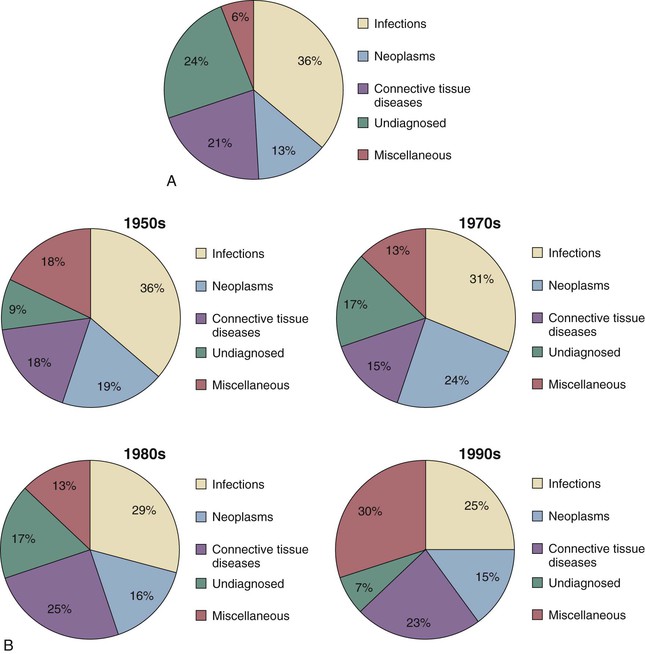

Of the many publications concerning the etiology of FUO,3,4,9–15 most have dealt with classic FUO rather than with the three other more recently defined subclasses listed earlier.7 Over the years a recurrent theme has become clear: of the myriad disorders causing classic FUO, almost all fall within one of five categories: infections, neoplasms, connective tissue diseases, miscellaneous other disorders, and undiagnosed illnesses. The relative frequencies of individual diagnoses within these five categories vary depending on the decade, geographic region, ages of the patients, type of medical practice, and other factors (Fig. 56-1).

In more recent series, infections have comprised the largest category, accounting for 14% to 58% of cases.4 However, in patients older than 65 years, infections become less common, falling into second or third place as a cause of classic FUO.4,8,9 In the series of Knockaert and associates,9 infection was the cause of FUO in only 25% of cases 65 years of age or older; temporal arteritis and various connective tissue diseases accounted for 31% of cases, and tumors accounted for 12%. Only 8% of cases went undiagnosed, which was a similar percentage reported by Colpan and colleagues14 but one substantially lower than that reported in surveys involving younger adults, in which as many as 30% of cases remain undiagnosed.16 The longer the duration of fever before medical consultation, the less likely that a definitive diagnosis will be made.17

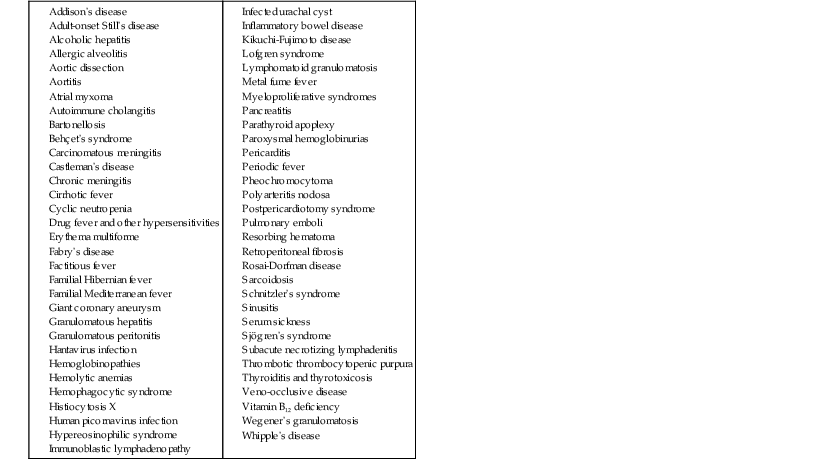

Among the infections responsible for classic FUO, abscesses, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and complicated urinary tract infections have consistently been among the most important. These tend to vary in incidence according to locale. Visceral leishmaniasis, for example, although absent from most series of classic FUO, accounted for 8% of cases in a study reported in 1997 from Spain.18 Other examples of causes of classic FUO in distinct populations include familial Mediterranean fever in Ashkenazi Jews; Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, an unusual form of necrotizing lymphadenitis seen primarily in Japan19; and TRAPS (tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever), formerly called familial Hibernian fever, an inherited periodic fever syndrome described originally in Ireland.20 The miscellaneous category contains both varied and individually rare causes of classic FUO (Table 56-2).

TABLE 56-2

Examples of Rare Miscellaneous Causes of Fever

Modified from Durack DT. Fever of unknown origin. In: Mackowiak PA, ed. Fever. Basic Mechanisms and Management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:237-249.

Of the connective tissue diseases responsible for classic FUO, Still’s disease (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), other variants of rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus predominate in younger patients, whereas temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica syndromes are more common in elderly patients.

Malignant neoplasms, another important cause of FUO, can induce fever directly through the production and release of pyrogenic cytokines, as in the case of certain lymphomas. They may also generate fevers indirectly by undergoing induced or spontaneous necrosis and/or by creating conditions conducive to secondary infections.1 Among the malignant neoplasms responsible for FUO, hematologic cancers, hypernephromas, and gastrointestinal (mainly colorectal cancers) and central nervous system cancers have been documented as common causes.3,4 In a recent series of 80 patients with FUO, Ergonul and colleagues8 established a malignant neoplasm etiology in 14 (18%) cases.

The relative frequency with which the major diagnostic categories are represented in series of classic FUO varies according to both the era in which the series was published6,13 and its country of origin (Fig. 56-2).4,8,15,21–24 Since the mid 1900s, the frequency with which infections and malignant neoplasms have been identified as causes of classic FUO has fallen steadily, whereas the proportion of miscellaneous causes and undiagnosed conditions has risen.24 However, in developing countries, the frequency with which infections are diagnosed has changed little.15 Consequently, in these countries malignant neoplasms and connective tissue disorders are comparatively less important as causes of classic FUO than in developed countries.15

Infants and Children

The diseases responsible for classic FUO in infants differ from those in older children and adults. Respiratory infections cause classic FUO in infants more often than in children older than 12 months or in adults.10 The relative frequency of infections as the cause of FUO in infants is high because connective tissue diseases and cancers are rare in this age group. Kawasaki disease occurs predominantly in children younger than 5 years. Whereas connective tissue diseases are rarely seen in children younger than 12 months, Still’s disease is a leading cause of FUO in older children and young adults. Joint involvement in children with FUO usually signifies a serious underlying disorder, such as a connective tissue disease, endocarditis, or leukemia.10

In a series of 146 pediatric cases of FUO, Jacobs and Schutze25 established a specific diagnosis in only 84 (57.5%). Of these, 64 (43.8%) had infections, 11 (7.5%) had autoimmune disorders, 4 (2.7%) had malignant neoplasms, and 5 (3.4%) had a variety of other disorders, such as drug-induced fever, sarcoidosis, and mercury poisoning. The most common infectious diseases diagnosed in their series were Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection (15%), osteomyelitis (10%), bartonellosis (5%), and urinary tract infections (4%).

Chow and Robinson26 analyzed 18 papers concerned with pediatric FUO published between 1968 and 2008. Of 1638 children, age birth to 18 years, 832 (51%) had infections, 93 (6%) had malignant neoplasms, 150 (9%) had noninfectious inflammatory diseases, 179 (11%) had miscellaneous causes, such as inflammatory bowel disease and Kawasaki disease, and 384 (23%) had no diagnosis. Although the distribution of diagnostic categories was similar among developed versus developing countries, urinary tract infections, brucellosis, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever were more common in developing countries. The most common infections diagnosed in cases of FUO in developed countries included urinary tract infections, osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, and bartonellosis.

Although a daily rectal temperature greater than 38.3° C (100.9° F) lasting more than 2 weeks despite diagnostic evaluation has been defined as FUO in children, 9 of 18 papers analyzed by Chow and Robinson used the classic definition of FUO.26

Elderly Persons

One of the most striking features of classic FUO in patients older than 65 years is the relatively high frequency with which connective tissue diseases are identified as the cause of the illness (Table 56-3).4,9,27–30 In developed countries, connective tissue diseases surpass even infections as the leading cause of classic FUO in the elderly.4,9,29 This is primarily because the temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica syndromes are common in this setting.4,29–31 Unfortunately, these diagnoses are frequently missed or delayed because their symptoms are subacute and nonspecific. In elderly patients in whom infections are identified as the cause of FUO, intra-abdominal abscesses, complicated urinary tract infections, tuberculosis, and endocarditis have predominated.9 For unclear reasons, factitious fever is a rare cause of FUO in older adults. Relatively few cases of FUO go undiagnosed in elderly patients (see Table 56-3). The occurrence of classic FUO in an elderly patient has a distinctly poorer prognosis than for the younger patient because of the relatively high incidence of malignancies in the elderly.32

TABLE 56-3

Final Diagnosis in Elderly Compared with Younger Patients with Fever of Unknown Origin

| DIAGNOSIS | <65 YR (n = 152) | >65 YR (n = 201) |

| Infections | 33 (21%) | 72 (35%) |

| Abscess | 6 | 25 |

| Endocarditis | 2 | 14 |

| Tuberculosis | 4 | 20 |

| Viral infections | 8 | 1 |

| Other | 13 | 12 |

| Tumors | 8 (5%) | 37 (19%) |

| Hematologic | 3 | 19 |

| Solid | 5 | 18 |

| Multisystem diseases* | 27 (17%) | 57 (28%) |

| Miscellaneous† | 39 (26%) | 17 (8%) |

| No diagnosis | 45 (29%) | 18 (9%) |

* Rheumatic diseases, connective tissue disorders, vasculitis (including temporal arteritis), polymyalgia rheumatica, and sarcoidosis.

† Includes factitious fever (seven cases), habitual hyperthermia (five cases), and drug-induced fever (three cases).

Modified from Iikuni Y, Okada J, Kondo H, et al. Current fever of unknown origin 1982-1992. Intern Med. 1994;33:67-73; and Knockaert DC, Vanneste LJ, Bobbaers HJ. Fever of unknown origin in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:1187-1192.

Returned Travelers

Fever in returned travelers (see Chapter 324) is most often due to common infections, such as malaria and respiratory or urinary tract infections.31,33 However, exotic causes of fever that typically fall short of the duration for FUO, such as amebic liver abscess or dengue, are occasionally diagnosed, especially among international travelers returning from the tropics. Of the many febrile conditions encountered among returning travelers (Table 56-4), malaria, typhoid fever, and acute HIV infection are the ones most likely to manifest as FUO.

TABLE 56-4

Causes of Fever in the Returned Traveler

| DIAGNOSIS | PERCENTAGE | |

| Maclean et al91 (n = 587) | Doherty et al92 (n = 195) | |

| Malaria | 32 | 42 |

| Hepatitis | 6 | 3 |

| Respiratory tract infection* | 11 | 2.6 |

| Urinary tract infection/pyelonephritis | 4 | 2.6 |

| Dysentery | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| Dengue fever | 2 | 6.2 |

| Enteric fever | 2 | 1.5 |

| Tuberculosis | 1 | 2 |

| Rickettsial infection | 1 | 0.5 |

| Acute HIV infection | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Amebic liver abscess | 1 | 0 |

| Other miscellaneous infections | 4.3 | 9.2 |

| Miscellaneous noninfectious causes | 6 | 1 |

| Undiagnosed | 25 | 24.6 |

* Includes upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, and bronchitis.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Modified from Suh KN, Kozavsky PE, Keystone JS. Evaluation of fever in the returned traveler. Travel Med. 1999;83:997-1017.

Nosocomial (Health Care–Associated) Fever of Unknown Origin

Nosocomial (health care–associated) FUO, as the name implies, is a condition in which patients first manifest fever during active medical treatment for some other illness. Such FUO cases, as might be expected, are frequently attributable to risk factors encountered in the health care environment, including surgical procedures, urinary and respiratory tract instrumentation, intravascular devices, drug therapy, and immobilization. Leading examples of causes attributable to health care–associated FUO include drug fever, postoperative complications (i.e., occult abscesses), septic thrombophlebitis, recurrent pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, cancers, blood transfusion, and Clostridium difficile colitis.4,7,34

Postoperative Patients

Several reports have highlighted the fact that it is often difficult to identify the precise cause of postoperative fevers. In a series of 537 consecutive patients undergoing major gynecologic surgery, 211 (39%) developed postoperative fever.35 Of 77 blood cultures performed on these patients, none was positive. Although 11 of 106 (10%) urine cultures were positive and 5 of 54 (9%) chest radiographs were abnormal, a specific pathologic process was detected in only 8% of febrile patients. In a prospective study by Kendrick and colleagues36 of postoperative fever among 292 patients admitted to a gynecologic oncology service after abdominal or vaginal operation, 58 (20%) patients developed postoperative fever. Among 37 (16%) low-risk surgical patients developing postoperative fever, only 6 (3%) had an infection diagnosis. The majority of infections occurred within 4 days of the operative procedure and included pneumonia, vaginal cuff cellulitis, and urinary tract infection. The authors proposed that postoperative fever is common and frequently represents the response to surgically induced tissue injury with the release of pyrogenic cytokines and interleukins rather than the result of infection. Although fever is a well-recognized manifestation of some surgical procedures, most episodes are short-lived and do not meet the classic definition of FUO. Postoperative fevers generally do not require extensive diagnostic investigation for unusual causes of fever.

In another series concerned with the etiology of persistent postoperative fever in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty, few definitive diagnoses were established, causing the authors to conclude that postoperative fever (postoperative days 1 through 5) is a normal component of the inflammatory response to this type of major surgery.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree