Summary of Key Points

- •

Bronchovascular sleeve resection is an essential technique for general thoracic surgeons to preserve as much as possible the patient’s lung function and quality of life after pulmonary resection.

- •

Previous reports suggested that the incidence rates of bronchopleural fistula and surgical mortality after sleeve lobectomy and sleeve pneumonectomy were 3% and 2.5%, and 5.5% and 20.9%, respectively.

- •

In the tissue-healing process of the anastomotic site after bronchial sleeve resection, previous reports suggested that the blood flow in the bronchial arteries proximal to the anastomosis comes from the aorta, but the blood flow distal to the anastomosis comes from the pulmonary artery.

- •

There are controversies in techniques of bronchial sleeve resections regarding suturing methods, suturing layers, types of anastomosis, types of sleeve resection, and the necessity of wrapping the anastomosis.

- •

There are controversies in techniques of pulmonary artery angioplasty regarding types of resection, types of reconstruction, order of reconstruction in a double sleeve resection, and the necessity of anticoagulant therapy.

Bronchoplastic and angioplastic procedures are essential techniques in general thoracic surgery. When performing lung cancer operations, thoracic surgeons sometimes encounter situations that require these techniques; therefore thoracic surgeons should know how to perform these procedures. This chapter describes the history of, and strategy and techniques for, bronchoplastic and angioplastic surgical procedures.

History and Surgical Outcomes of Bronchovascular Sleeve Resection

Bronchial Sleeve Resection

The first bronchoplastic surgical procedure was described by Bigger in 1932. The patient was a 14-year-old boy with a tumor in the left main bronchus, and the tumor was removed with an incision in the bronchus. Postoperative examination of the pathologic specimen indicated that the resected tumor was malignant. Therefore a week after the surgical procedure, a left pneumonectomy was done. However, the patient died of infectious pericarditis after these repeated thoracotomy procedures. The first bronchial sleeve resection was performed by Thomas in 1947. The patient was a young man who was awaiting a commission in the Royal Air Force. An adenoma on the right upper lobe bronchus was detected at clinical examination, and the tumor was found to be occluding the right main bronchus. A sleeve resection and an end-to-end anastomosis of the right main bronchus were performed. The patient was able to serve as an Air Force pilot in active flying duties after this lung-preserving operation.

In 1959, Johnston and Jones described the first successful sleeve lobectomy for primary lung cancer, a procedure that had been performed by Allison in 1952. In 1955, Paulson and Shaw named this procedure a “bronchoplastic surgery.” In the 1970s and 1980s, Jensik et al., Bennett and Smith, and Faber et al. reported on case series of patients who had sleeve lobectomies. The first report of a carinal resection was made by Mathey et al. in 1966, and in 1978, Grillo reported success with 38 cases.

The results of bronchoplastic procedures have been reported in several studies ( Table 31.1 ). In most of these reports, 5-year survival rates were 40% to 50% and mortality rates were relatively low, ranging from 0% to 7.5%. Tedder et al. reviewed the results of 1915 bronchoplastic procedures for primary lung cancer that were performed over 12 years, starting in 1979. According to that report, the incidence rates of bronchopleural fistula, bronchovascular fistula, and surgical mortality after sleeve lobectomy and sleeve pneumonectomy procedures were 3% and 10.1%, 2.5% and 2.9%, and 5.5% and 20.9%, respectively.

| Reference | No. of Patients | Mortality (%) | 5-Year Survival Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tedder et al. (1992) | 1915 | 7.5 | 40 |

| Van Schil et al. (1996) | 145 | 4.8 | 46 |

| Rea et al. (1997) | 217 | 6.2 | 49 |

| Icard et al. (1999) | 110 | 2.8 | 39 |

| Kutlu et al. (1999) | 100 | 2.0 | 49 |

| Tronc et al. (2000) | 184 | 1.6 | 52 |

| Okada et al. (2000) | 151 | 0 | 48 |

| Rendina et al. (2000) | 145 | 3.0 | 38 |

| Deslauriers et al. (2004) | 300 | 2.7 | 54 |

| Ludwig et al. (2005) | 116 | 4.3 | 43 |

| Yildizeli et al. (2007) | 218 | 4.1 | 43 |

Pulmonary Artery Angioplasty

Gundersen published the first report of a pulmonary artery sleeve resection in 1967. That report described two cases of successful pulmonary artery sleeve resection and end-to-end anastomosis. After the publication of these results, many successful cases were reported. More recently, an increasing number of studies have described the results of concurrent bronchoplasty and pulmonary artery angioplasty procedures ( Table 31.2 ). For example, Rendina et al. reported on 40 cases of concurrent procedures. The 5-year survival rate was 38.6%, which was equivalent to the 5-year survival rate of 38.7% recorded for 80 cases of only bronchoplastic surgical procedures.

| Reference | No. of Patients | Mortality (%) | 5-Year Survival Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Icard et al. (1999) | 16 | NA | 39 |

| Rendina et al. (2000) | 40 | 0 | 39 |

| Okada et al. (2000) | 21 | 0 | 48 |

| Fadel et al. (2002) | 11 | 0.7 | 52 |

| Chunwei et al. (2003) | 21 | NA | 33 |

| Lausberg et al. (2005) | 67 | 1.5 | 43 |

| Nagayasu et al. (2006) | 29 | 17.2 | 24 |

Healing of the Anastomotic Site After Bronchial Sleeve Resection

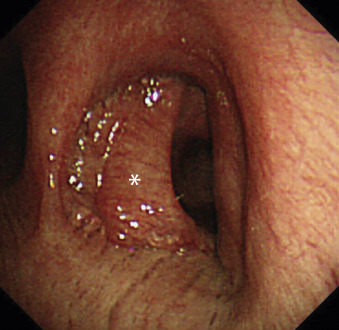

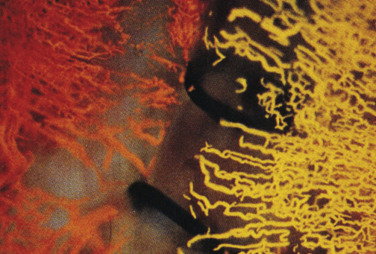

Ishihara et al. detailed the results obtained in animal models regarding the tissue-healing process of the anastomotic site after bronchial sleeve resection. He injected silicone rubber of different colors into the bronchial artery and pulmonary artery after a sleeve lobectomy. The results confirmed that the blood flow in the bronchial arteries proximal to the anastomosis came from the aorta, but the blood flow distal to the anastomosis came from the pulmonary artery ( Fig. 31.1 ). Inui et al. evaluated bronchial blood flow by laser Doppler velocimetry in dogs. Their results suggested that the bronchial mucosal blood flow was reduced when the peribronchial tissue was detached, and blood flow was restored by dressing the anastomosis with the greater omentum.

According to some reports, systemic administration of small doses of steroids after the bronchoplastic procedure prevented an inflammatory reaction and edema in the tissue around the anastomotic site. Consequently, this treatment was believed to improve blood flow and promote healing of the anastomosis. However, Inui et al. suggested that treatment with steroids did not improve blood flow at the anastomotic site in animal models as evaluated by laser Doppler velocimetry. Rendina et al. reported that treatment with steroids in the clinical setting substantially decreased the incidence of postoperative morbidity and shortened the postoperative intensive care unit and hospital stays. The patients in that study received postoperative aerosol steroid inhalation three times per day and intravenous injections of 10 mg methylprednisolone twice a day.

Surgical Techniques and Controversies Regarding Bronchial Sleeve Resections

Suturing Method: Interrupted or Continuous?

The first question for the optimal selection of a suturing method is whether an interrupted or continuous suture should be used. It is generally thought that a continuous suture allows less blood flow at the anastomotic site than an interrupted suture. Reduced blood flow could lead to anastomotic dehiscence or stenosis; therefore the interrupted suture has been adopted in many institutions. However, Kutlu and Goldstraw and Aigner et al. reported good results with a continuous suture technique. Bayram et al. found no pathologic differences in the healing process between dogs treated with interrupted and continuous sutures.

The greatest concern about a continuous suture technique is that if part of an anastomosis develops dehiscence, the defect might propagate over the whole anastomosis. This possibility may explain why many thoracic surgeons are reluctant to adopt the continuous suture technique. Hamad et al. reported a new bronchial anastomosis technique, which uses three running sutures. They showed that this technique could be performed easily and quickly with few knots, and it minimized the risk of a whole anastomosis dehiscence, even after difficult sleeve resections.

The advantage of a continuous suture is that it is technically easier than an interrupted suture, particularly for a mini-thoracotomy procedure. The innovation of absorbable monofilament sutures made continuous suture techniques easy and safe. Nevertheless, the advantage of the interrupted suture is that it maintains good blood flow at the anastomosis. Furthermore, if a partial dehiscence occurs, the whole anastomosis would not be compromised. The disadvantage of the interrupted suture is that tying several posterior sutures with knots on the outside of the anastomosis is technically difficult. However, current advances have made it possible to place several posterior suture knots on the inside of an anastomosis, which should be more convenient and technically easier to perform. When absorbable monofilament sutures are used in this procedure, airway complications can be avoided because the knots are readily absorbed, provoke little tissue reaction, and create minimal bronchial obstruction.

Suturing Layers: Through-and-Through or Submucosal Suture?

Two methods are used for suturing the cartilaginous portion of the bronchus. One method is to place the suture outside the mucosal layer, for the so-called submucosal suture; the other method is to pierce through the whole wall of the bronchus, for the so-called through-and-through suture. Paulson and Shaw demonstrated the effectiveness of the submucosal suture using interrupted fine cotton or cable-wire sutures. Rendina et al. also recommended using the submucosal suture with the aid of magnifying loupes. However, no evidence has supported the usefulness of the submucosal suture; thus in many institutions, the whole-wall suture has been performed with use of an absorbable monofilament thread. This method is preferred for two reasons. First, the submucosal suture is technically more difficult than the whole-wall suture. Second, the monofilament absorbable suture is unlikely to develop anastomotic complications from infection associated with the thread. This type of infection may occur with either a submucosal suture or a through-and-through suture and may result in collection of sputum and anastomotic stenosis.

Type of Anastomosis: Telescope or End-To-End?

Two methods are used for creating a bronchial anastomosis: the telescope and the end-to-end methods. The telescope anastomosis is currently used when a large-caliber mismatch is present between the bronchial ends. This method does not require a tissue wrapping for the anastomosis, and many good results have been reported to date, particularly in lung transplantation procedures. However, some transplant surgeons have reported disadvantages of the telescope anastomosis. The primary disadvantage is that the retrograde collateral blood flow from the pulmonary artery of the residual lung may be insufficient at the overlapping edges of the distal bronchus; therefore this method may lead to necrosis and stenosis at the anastomosis. The mortality rate for patients with stenosis after a telescope anastomosis is reportedly 2% to 3%. Aigner et al. reported that the incidence of anastomotic complications associated with the telescope technique was 30% in the early 1990s. Converting to the end-to-end bronchial anastomosis markedly reduced the complication rate to less than 4%. Rabinov et al. suggested that the “reverse telescope” anastomosis technique greatly reduced the incidence of anastomotic stenosis.

Type of Sleeve Resection: Wedge or Conventional?

When the tumor invades a very small area of the central bronchial wall or when it is considered to be a low-grade malignant tumor that requires only a small surgical margin, a wedge sleeve resection can be performed instead of a conventional sleeve resection. The wedge resection maintains the blood flow of the bronchial anastomosis because a small area of the bronchial wall remains connected. However, this procedure may cause a deformed airway to develop, which may result in sputum retention at the anastomotic site ( Fig. 31.2 ). Moreover, tension at the anastomosis may become excessive. In such cases, it is recommended to convert to the conventional sleeve resection. Rendina et al. suggested that a sleeve resection is always preferable to a wedge sleeve resection because the latter procedure caused a number of complications as a result of excessive tension.