INTRODUCTION

Several human neoplasms, including gastric carcinoma (GC), develop in close association with infectious organisms.

Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are now regarded as causative microorganisms of GC.

1,2 Like other human oncogenic microorganisms, these infectious agents cause malignant neoplasms to develop in a limited number of patients out of a large population of healthy or healthy-appearing carriers through unknown mechanisms.

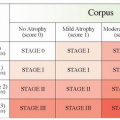

2 However, the roles of

H. pylori and EBV in the development and progression of GC are quite different (

Table 4-1).

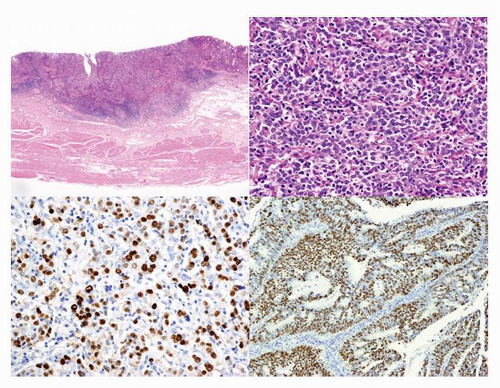

EBV was the first human oncogenic virus to be identified when it was discovered in human neoplastic cells (Burkitt lymphoma cell lines) in 1964. Subsequent investigations have identified the virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), Hodgkin lymphoma, B-cell lymphomas with or without immunosuppression, and nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. EBV was identified in GC tissues in 1990 (

Fig. 4-1), when the in situ hybridization (ISH) method for detecting EBV-encoded small RNA

(EBER) had just been introduced to the field of pathology (

Fig. 4-1C and D).

3 EBER is abundant in latently infected cells (up to 10

7 copies per infected cell) and is identified in nearly all neoplastic cells of tumor tissues when it is present in GC. Thus, detection of

EBER by ISH is a gold standard for the identification of EBV-associated GC. Furthermore, ISH can be used to identify

EBER in archived materials, such as formalin-fixed and paraffinembedded tissues, which can be used to investigate the epidemiology of this type of GC. EBVassociated GC occurs worldwide and its frequency is estimated to be 8.7% (95% confidence interval: 7.5%-10.0%) of all GC cases,

4 which corresponds to an annual incidence of 70,000 to 80,000 patients worldwide.

1

EBV-ASSOCIATED GC IS A DISTINCT CLINICOPATHOLOGICAL SUBGROUP OF GC

EBV-associated GC is defined as the presence of latent EBV infection in neoplastic cells. This type of GC (

Table 4-2)

4, 5 and 6 affects predominantly males and is usually located in the proximal stomach. Some reports suggest that this carcinoma occurs in patients of a relatively younger age compared to those with non-EBV GC, but meta-analyses did not confirm that observation.

4,5 EBV is involved in 25% of remnant GCs, that is, GC, which occurs in the remnant stomach, at least >5 to 10 years after the initial gastrectomy for either benign or malignant stomach diseases, and several reports have suggested that multiple carcinomas are likely to occur in association with EBV

6 EBV-associated GC has a lower rate of lymph node involvement, especially during its early stage

within the submucosa, and has a relatively favorable prognosis compared with EBV-negative GC, although both findings remain to be confirmed.

5EBV-associated GC often occurs as an ulcerated or saucer-like tumor accompanied by marked thickening of the gastric wall (

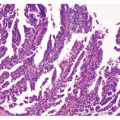

Fig. 4-1A). These features are easily discernible on endoscopic ultrasonograms and CT scans of the stomach. There are two histological types of EBV-associated GCs, lymphoepithelioma (LE)-like (

Fig. 4-1B and C) and ordinary (

Fig. 4-1D), although there is a continuum between the types.

6 The typical morphology of LE-like GC is described as poorly

differentiated carcinoma with dense infiltration of lymphocytes, resembling NPC.

3 LE-like GC is nearly identical to the subgroup that Watanabe et al.

7 reported as “GC with lymphoid stroma (GCLS),” but GCLS is relatively a broad category that includes LE-like GC. The relative ratio of the LE-like/GCLS type to the ordinary type reported in the literature varies considerably from 1:10 to 4:1.

6 This variability is due to interpretation variability in diagnostic criteria of the LE-like/GCLS type, especially when there is heterogeneity within the tumor. More than 80% of the LElike/GCLS-type tumors were positive for EBV in most reports.

3,6,8 The histopathological features of EBV-positive LE-like/GCLS tumors, which are not seen in EBV-negative LE-like/GCLS tumors, are mild cellular pleomorphism, rare mitotic figures, a marked degree of lymphoid stroma, and lymphoid infiltration within the cancer cell nests.

8For EBV-associated GC, the incidence of intramucosal and submucosal carcinomas (early GC) at diagnosis is not statistically different from that of deeply invasive carcinomas (advanced GC). At the intramucosal stage, EBV-associated GC shows a “lace pattern,” which is formed by the connection and fusion of neoplastic glands within the mucosa proper. Further invasion of the carcinoma into the submucosa is frequently accompanied by the infiltration of massive lymphocytes (

Fig. 4-1A) consisting of CD8-positive T lymphocytes, CD4-positive T lymphocytes, and CD68-positive macrophages, in a ratio of 2:1:1, respectively. EBV infection is observed in only a very limited number of these infiltrating lymphocytes. Infiltrating cells are sometimes variable, and their extreme effect is prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with numerous Mott cells

9 or a granulomatous reaction with many osteoclast-like giant cells (Ushiku et al.,

Pathol Int. 2010;60:551-558).

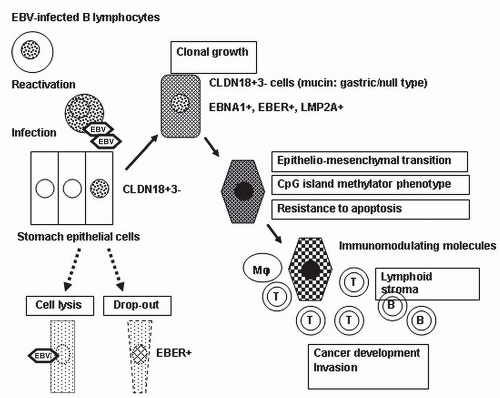

EBV INFECTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF CARCINOMA

The evidence regarding the lineage of EBV-infected cells, the clonality of EBV in infected cells, and the infection of epithelial cells by EBV, as described below, strongly suggests that stomach epithelial cells initiate clonal growth after they are infected with EBV from the reactivation of EBV-carrying lymphocytes at the mucosa (

Fig. 4-2).

Lineage of EBV-infected Cells

Neoplastic cells from EBV-associated GC show characteristic profiles of differentiation markers, which might be associated with the lineage of EBV-infected cells. Claudin (CLDN) proteins

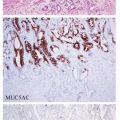

constitute the tight junction, and neoplastic cells of EBV-associated GC showed a high frequency of CLDN18 expression (84%) and a low frequency of CLDN3 expression (5%).

10 This expression profile (CLDN18+, 3-) corresponds to that of the normal gastric epithelium in adults and fetuses, but not to that of intestinal metaplasia (CLDN18-, 3+). In accordance with the CLDN expression patterns, almost half of the EBV-associated GC cases in a study by Barua et al.

11 had gastric-type mucin expression (MUC5AC, MUC6), and the other half lacked gastric- or intestinal-type mucin or CD10 expression. These results indicate that EBV-associated GC is very homogenous with regard to cellular differentiation and that it preserves the nature of the cells of origin. Thus, the cells that are targets of EBV infection and their subsequent transformation may be precursor cells with intrinsic differentiation potential toward the gastric cell type.

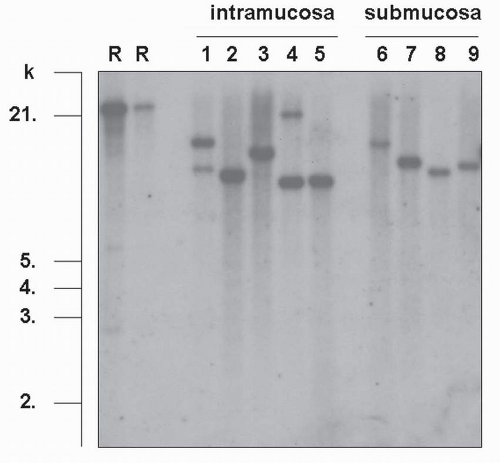

Clonality of EBV in Infected Cells

EBV is a double-stranded DNA virus (184 kb in size), which is maintained in a linear form in the virus particles. After EBV enters infected cells, the viral DNA circularizes by fusing the terminal repeats (TRs, repetitive 500-bp structures) at both ends of the linear genome and maintains its circular form in the nuclei of latently infected cells.

2 Southern blot analysis of EBV-TRs provides information about the clonality of EBV and the state of viral activation, that is, replicating (linear configuration) versus latent (episomal circular forms). In EBV-associated GC, TR analysis has demonstrated that monoclonal EBV is present in an episomal form without integration into the

host genome and infection is latent, with no viral replication. Monoclonal or biclonal EBV was observed in carcinoma tissues in the intramucosal stage; however, it was always monoclonal in the submucosal invasion stage (

Fig. 4-3) and in more advanced carcinomas.

12,13 Since all carcinoma cells show a positive signal in

EBER-ISH in all cases of EBV-associated GC, EBV infection must occur at the initial or a very early stage of carcinoma development.

EBV Infection in Epithelial Cells