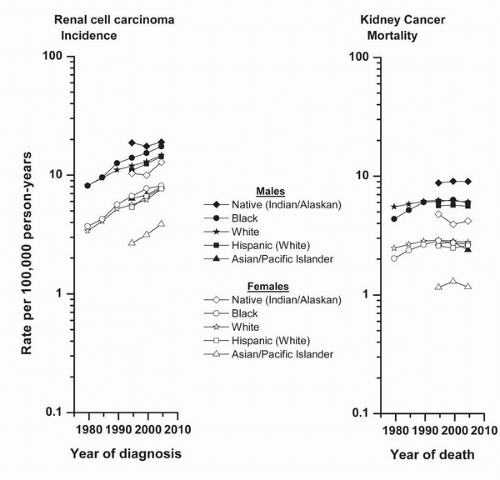

Total kidney cancer incidence rates have been reported recently to show signs of leveling or declining since the mid-1990s in many countries worldwide, following notable increases during earlier years (

3,

9). In the United States, where long-term incidence data are available for subtype of kidney cancer (

10), RCC incidence rates have continued to rise for over three decades while rates for renal pelvis cancer have declined (

11). Rising incidence rates were apparent among white and black men and women during 1977 to 2006, and among men and women of other minority racial/ethnic groups during 1992 to 2006 when data were available for Hispanics, Asians, and Natives (

Fig. 38.3). During 1992 to 2006, the most rapid increases in men occurred among Hispanics (31.1%), and in women, among Asians (44.9%) followed by Hispanics (43.1%). Of note, incidence rates for Native women approach those for white and Hispanic men, whereas rates for Asian men are comparable to those for non-Asian women. Increases in total kidney cancer mortality rates were less rapid than those for RCC incidence, and rates have leveled across all racial/ethnic groups in the United States since the early 1990s (

12). These changing mortality trends are consistent with downward trends already reported in some countries in the European Union (

9).

The rising RCC incidence rates over time in the United States occurred across all adult age-groups among both blacks and whites during 1977 to 2006 (

10) (

Fig. 38.4). According to stage at diagnosis, increases were seen mainly for localized cancers. There is little evidence of upward trends in rates for more advanced tumors, including those of regional and distant stage, or unstaged. Tumor size at diagnosis has been available in the SEER data since 1983 (

2). Contrary to the pattern for stage at diagnosis, rates increased for cancers of all sizes during 1992 to 2006, except for tumors with unknown size. By far, the most rapidly rising rates were for cancers <2.0 cm, suggesting that heightened clinical surveillance or improved diagnostic capabilities might have contributed to the detection of these small tumors. The temporal patterns by age-groups, stage at diagnosis, and tumor size were similar for all other minority groups (data not shown in figure).